Полная версия

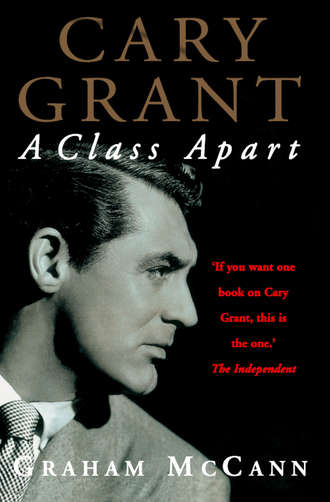

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

It is not even clear whether or not Cary Grant lived his life believing himself to be Jewish. His closest friends – indeed even his wives – have offered conflicting information and opinions on the matter. In the early 1960s, for example, Walter Matthau, who had heard the rumours that Grant was Jewish, was surprised when Grant denied it. ‘So, I asked him why everyone thought he was. He said, “Well, I did a Madison Square Garden event for the State of Israel and I wore a yarmulke.” He pronounced the r in “Yarmulke”. An Englishman wouldn’t pronounce the r, so I still think he might be Jewish. Besides, he was so intelligent. Intelligent people must be Jewish.’21 There is no reason to think that Grant would have tried deliberately to hide his Jewishness: he was a uniquely powerful and consistently popular star, less easily intimidated than most by anti-Semitic producers and gossip columnists, and he was a frequent contributor to, and supporter of, Jewish charities.22

If all (or even most) of the testimonies by his friends are sincere, one has to acknowledge that Grant gave some people the impression that he was Jewish and others that he was not. The extraordinary farrago of conjecture, confusion and wild theorising that this apparent inconsistency has engendered is at times almost comic in its incoherence. An outstandingly bizarre example is the contribution made by Grant’s first wife, Virginia Cherrill, who was convinced (on the rather scant evidence of his deep tan and the fact that he could perform a temsulka, which is a word of Arabic derivation for a special double forward somersault) that he was of Arabic origin.23 In 1983, Grant – then aged seventy-nine, long retired from acting and surely at a stage in his life when it made no sense to continue to be dishonest or evasive about such a matter – replied to a fan’s question about his late ‘Jewish mother’ by stating that she was not Jewish.24

The theory which has been most controversial, however, was put forward shortly after Grant’s death by two of his most assiduous biographers, Charles Higham and Roy Moseley.25 They claimed, with a suitably bold theatrical flourish, that Grant had been ‘the illegitimate child of a Jewish woman, who either died in childbirth or disappeared’.26 Although this thesis helps to make sense of the circumcision and of the possible reasons for Grant’s own inconsistent references to his background (Jews define Jewishness through the maternal line), it is not based on any documentary proof. Indeed, the authors strain one’s credulity with their scattershot references to such ‘circumstantial evidence’ as the fact that Grant’s relationship with his mother in later years appeared ‘artificial and strained’27 to some observers, and that ‘she consistently refused to visit Los Angeles’28 once Grant was established as a star. They do, however, make use of two further facts which are rather more intriguing: one is that, until 1962, Grant, in his entry in Who’s Who in America, listed his mother’s name as ‘Lillian’, not Elsie, Leach; the other is that in 1948 he donated a considerable sum of money to the new State of Israel in the name, according to the authors, of ‘My Dead Jewish Mother’.29

It is quite true that, until 1962, it is ‘Lillian Leach’ who is listed in Who’s Who in America as being Grant’s mother;30 it is also true – although Higham and Moseley do not refer to it – that the 1941 article on Grant in Current Biography refers to his mother as ‘Lillian’, whereas the 1965 edition reverts, without any explanation, to ‘Elsie’.31 This discrepancy, while certainly noteworthy, is not, in itself, ‘proof of the existence of Grant’s ‘real’ mother: the entries in both publications contain numerous inaccuracies, such as the spelling of Elsie/Lillian Leach’s maiden name as ‘Kingdom’ rather than ‘Kingdon’ (one would have expected greater care if these entries had been intended to set the record straight), the description of Fairfield Grammar School as the more American-sounding ‘Fairfield Academy’ and the inverted order of Grant’s forenames as ‘Alexander Archibald’.32 Higham and Moseley do not make it clear why Grant took the seemingly perverse step of ‘disowning’ Elsie while she was still alive and in a fragile condition and then reclaiming her more than two decades later: such inconstancy, surely, merits some kind of explanation. Another puzzling detail, if one is to take seriously the interpretation of these entries as some kind of rare act of candour on Grant’s part, is why, after acknowledging his secret Jewish mother, he then proceeded to describe himself as a ‘member of the Church of England’.33

It is a bewilderingly odd little mystery. Higham and Moseley, having convinced themselves that the ‘real’ mother of Archie Leach was a mysterious and hitherto unknown Jewish woman called ‘Lillian’, struggle to weave her into the facts of his life in spite of having no documentary (or even anecdotal) evidence that she, or anyone like her, ever existed. They also fail to explain why Grant, once Elsie Leach had died in 1973, did not make any attempt to acknowledge the identity of his ‘real’ mother at any point during the remaining thirteen years of his life. Other accounts shed no light on the question of Grant’s alleged Jewishness or the reason for the absence of any records which could corroborate it. We are left, in short, with one of those intriguing puzzles which together with others make up a peculiar constellation of ambiguities in the life of Cary Grant.

The first few years in the life of Archie Leach were marked by both material and emotional impoverishment. The Leach family moved house several times during Archie’s childhood, and each change of address marked a further decline in the Leaches’ finances.34 ‘We could afford only a bare but presentable existence,’ he later recalled.35 It did not take long for Archie to become conscious of the fact that his mother and father were increasingly unhappy in each other’s company. There were ‘regular sessions of reproach’ as Elsie castigated Elias for his failure to provide the family with a better standard of living, ‘against which my father resignedly learned the futility of trying to defend himself’.36 Elias started drinking more heavily and frequently – often, it seems, in the company of women who were more convivial than his wife. ‘He had a sad acceptance of the life he had chosen,’ said Grant.37 Elsie – partly out of necessity, partly by inclination – became the disciplinarian of the family, working hard to keep her young son under control.

Looking back, Grant observed that his old photographs of Elsie Leach failed to do justice to the complexity of her adamantine character, showing her as an attractive woman, ‘frail and feminine’,38 but obscuring the full extent of her strength and her will to control. When Archie was born, she became – rather understandably given the circumstances – single-minded in her concern for his well-being (she had, superstitiously, waited six weeks before allowing Elias to register the birth) and during his childhood she remained, if anything, a little over-protective of him; she ‘tried to smother me with care’, he said, she ‘was so scared something would happen to me’.39 She kept him in baby dresses for several years, and then in short trousers and long curls. In an attempt to provide him with an opportunity to have a better and more rewarding life than his father’s, and in the belief that her son was a bright and talented boy, Elsie arranged for Archie to start attending the Bishop Road Junior School in Bishopston; he was only four-and-a-half years old, whereas five was the usual age for admission. She also managed, on an irregular basis, to save enough money to send Archie for piano lessons. Such forceful ambition was not, one should note, so unusual within a working-class family at the time; Charlie Chaplin also recalled how his mother would correct his grammar and generally work hard to make him and his brother ‘feel that we were distinguished’.40

Archie did not escape from his mother’s influence when he started attending school. Although few of his new schoolfriends came from poorer families than his own, Archie was eye-catchingly smart; Elsie made sure that he wore Eton collars made of stiff celluloid, and she had taught him always to raise his cap and speak politely to any adult he met. His pocketmoney was sixpence a week, but he seldom received all of it; Elsie would fine him twopence for each mark he made on the stiff white linen tablecloth during Sunday lunch. Elias was uncomfortable with the idea of such exacting, sometimes overly fastidious, strictures governing Archie’s upbringing, but he rarely interfered in matters concerning their son.

When Archie was eight years old, his father left the family for a higher-paying job (and, it seems likely, a clandestine love-affair) eighty miles away in Southampton. War had broken out between Italy and Turkey, and, while Britain was not involved directly, armament activities were accelerated. Elias was employed making uniforms for the armies. ‘Odd,’ said Grant, ‘but I don’t remember my father’s departure from Bristol … Perhaps I felt guilty at being secretly pleased. Or was I pleased? Now I had my mother to myself.’41 The job only lasted six months, in part because of the considerable financial strain on Elias of maintaining two households. He was, however, fortunate that, with so many workers entering into war-related industries at that time, his old presser’s job in Bristol was still vacant on his return.

Elias and Elsie were living together again, but their marriage had disintegrated further. Absence had hardened their hearts; neither person cared enough to communicate with the other. Elias was rarely to be found at home, preferring instead to spend most of his free time in pubs, and, when he returned in the evenings, he would retire immediately after finishing his meal in order to avoid any further confrontations with Elsie. Although Archie was often overlooked during this increasingly tense period, his parents would sometimes, separately, make an effort to entertain him.

Both Elsie and Elias enjoyed visiting the local cinemas, but, typically, they each did their movie viewing in their own distinctive way. Archie’s mother would, on the odd occasion, take him to see a movie at one of the more ‘tasteful’ cinemas in town; he soon became addicted to the experience, and started going on his own or with schoolfriends to the Saturday matinees. 42 ‘The unrestrained wriggling and lung exercise of those [occasions], free from parental supervision, was the high point of my week.’43 Elias also found time to accompany him but, whereas Elsie usually favoured the rather refined atmosphere of the Claire Street Picture House (where tea and refreshments were served on the balcony during the intermissions and the movies tended to be romance and melodramas), Elias, who ‘respected the value of money’,44 preferred to take Archie to the bigger, brasher and cheaper Metropole (a barn-like building with hard seats and bare floors, where men were permitted to smoke, fewer women were present and the movies were usually popular thrillers – such as the Pearl White serials45 – comedies and westerns).

Archie was grateful for all such excursions, but he particularly enjoyed his visits to the Metropole. It was a loud, exciting place, with a piano accompaniment which, he recalled, tended to aim more for plangency than for any discernible tune. It showed the kind of movies and performers he liked most (such as slapstick comedies and stars like Charlie Chaplin, Chester Conklin, Fatty Arbuckle, Ford Sterling, Mack Swain and ‘Bronco Billy’ Anderson), and these occasions were probably the only times when he had the opportunity to establish any real rapport with his father, who sometimes treated him to an apple or a bar of chocolate.

Elias also took his son to the theatre. At Christmas it was pantomimes at such grand places as the Prince’s and Empire theatres. At other times of the year it was music-hall acts, such as magicians, dancers, comedians and acrobats. Elias, ‘in a tight-throated untrained high baritone’,46 taught his son how to mimic some of the singers of the time (in such songs as ‘I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls’ and ‘The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’), as well as encouraging him to learn some of the magic tricks he had seen. Archie was enchanted. He started to visit the theatre whenever he had the opportunity. He was often alone and unsettled at home, an only child who was ‘loved but seldom ever praised’,47 but now he had found an attractive distraction. ‘I thought what a marvellous place.’48

CHAPTER II A Mysterious Disappearance

Death merely acts in the same way as absence.

MARCEL PROUST

[I made] the mistake of thinking that each of my wives was my mother,that there would never be a replacement once she left.

CARY GRANT

Archie Leach was just nine years of age when it happened.1 He had just arrived home, shortly after five o’clock, after an ordinary, quiet, uneventful day at school. He was shocked to discover that his mother had disappeared. She had said nothing to him on the previous day to prepare him for her absence. No one, in fact, had said anything to suggest to him that his mother might not be waiting for him, as usual, at this particular time on this particular afternoon. It was, quite simply, a mystery.

His mother had, it was true, grown stranger, more unpredictable in temperament and behaviour, over the past few months, and he had been aware, to some extent, of the change. She had become increasingly – perhaps even obsessively – fastidious: Archie had noticed that she would sometimes wash her hands again and again, scrubbing them with a hard bristle brush; she would also lock every door in the house, regardless of the time of day, and she had taken to hoarding food; there had even been odd occasions when, inexplicably, she would ask no one in particular, ‘Where are my dancing shoes?’;2 and on some evenings she would sit motionless in front of the fire, saying nothing, gazing at the coals, the small room draped in darkness. Archie had also grown accustomed – but by no means immune – to the noisy quarrelling between his parents, as well as to the equally common periods of icy silence which usually followed these arguments.3 Nothing, however, prepared him for such a sudden and dramatic disappearance as this.

Two of his cousins were lodging in part of the house at the time, and, when he realised that his mother had gone, he sought them out to see if they knew of her whereabouts. According to one source, they told Archie that his mother ‘had died suddenly of a heart attack and had had to be buried immediately’.4 The more common version, however, first put forward by Grant himself, has Archie being told that his mother had gone to the local seaside town of Weston-super-Mare for a short holiday.5 ‘It seemed rather unusual,’ he recalled much later, with a bizarre attempt at English understatement which perhaps had come to serve, in public, as a relatively painless way of obscuring a painfully disturbing memory, ‘but I accepted it as one of those peculiarly unaccountable things that grown-ups are apt to do.’6

If his father attempted to reassure him that his mother would soon come home – and it seems that he did so – then it was not long before Archie realised that she was never going to return:

There was a void in my life, a sadness of spirit that affected each daily activity with which I occupied myself in order to overcome it. But there was no further explanation of Mother’s absence, and I gradually got accustomed to the fact that she was not home each time I came home – nor, it transpired, was she expected to come home.7

Towards the end of his life he admitted that, once some of the shock had worn off, ‘I thought my parents had split.’8

What had really happened to Elsie Leach was that her husband had committed her to the local lunatic asylum, the Country Home for Mental Defectives in Fishponds, a rustic district at the end of one of Bristol’s main tramlines.9 Elias had arranged for the hospital’s staff to collect her from their home earlier in the day, and then, after settling her in, he went back to work. He never told his son the truth about the matter.

The asylum at Fishponds was, by quite some way, the worst of the two institutions for the mentally ill in Bristol at that time. Conditions were filthy, and supervision negligible. It cost Elias just one pound per year to keep Elsie inside as a patient. She stayed there for more than twenty years, until, in fact, her husband’s death in the mid-1930s. Was he her gaoler? British law prohibits the unsealing of psychiatric case records until a hundred years after the patient’s death, and, as Elsie lived on until 1973, the actual reasons for her incarceration may remain ambiguous until well into the next century. Dr Francis Page, a Bristol physician, has said that it was ‘always presumed she was a chronic paranoid schizophrenic’, but he also acknowledged that he ‘never did know the official psychiatric diagnosis’ that had been used to keep her institutionalised.10 She was, it is clear, prone to periods of acute depression, and it is conceivable that she could have suffered a nervous breakdown at this time. It is not so obvious, however, why this in itself should have convinced Elias that the only possible solution would be to abandon her inside the most wretched institution he could find. Ernest Kingdon, a cousin, visited Elsie regularly in Fishponds, and he has insisted that he found her to be resilient and intelligent: ‘She used to write beautiful letters asking why she could not be released.’11

Although the precise state of Elsie Leach’s mental health remains a matter for speculation, it is much easier to establish the reasons why Elias Leach was prepared – or perhaps determined – to have her committed and out of his life. It was a fact – a fact that Cary Grant never acknowledged or commented on in public – that Elias Leach had a mistress, Mabel Alice Johnson. It might have been the shock of her husband’s indiscretion which precipitated Elsie’s breakdown, although, by that time, their marriage was probably not much more than a sham, and Elsie was unlikely to have been entirely unaware of her husband’s numerous earlier affairs. Divorce was both socially unacceptable and financially impracticable. Once Elsie was shut away, however, Elias was at liberty to establish a common-law marriage with his lover and, eventually, have a child with her.12

Archie Leach was kept ignorant of his father’s other family. He and his father moved in with Elias’s elderly mother, Elizabeth, in Picton Street, Montpelier, nearer to the centre of Bristol. Elias and Archie occupied the front downstairs living-room and a back upstairs bedroom, while Archie’s grandmother (whom he later remembered as ‘a cold, cold woman’13) kept to herself in a larger upstairs bedroom at the front of the house. This arrangement provided, at least in theory, someone to look after Archie while his father was spending time with his new family, and it saved Elias the expense of renting two separate houses for his double life.

Archie Leach never knew the full extent of the extraordinary deception perpetrated by his father.14 Cary Grant discovered the truth (or at least a part of it) two decades later, in Hollywood, after the death on 1 December 193515 of his father from the effects of alcoholism – or, as the official account put it, ‘extreme toxicity’16 – when a lawyer wrote to him from England to inform him that his mother was in fact still alive.17 Through the London solicitors Davies, Kirby & Karath, Grant arranged for the provision of an allowance and moved her to a house in Bristol. Elsie Leach was fifty-seven years old, her son thirty-two. She barely recognised the tall, well-dressed sun-tanned star who arrived back in England to be reunited with her. ‘She seemed perfectly normal,’ Grant would recall, ‘maybe extra shy. But she wasn’t a raving lunatic.’18 As Ernest Kingdon put it, ‘Cary Grant knew very little of his mother. She was a stranger. Late in life, they had to come together and learn to know each other. It was a tragedy, really – a great tragedy.’19

Suddenly to re-acquire a mother in one’s early thirties must have been, to say the least, a strange experience, just as the sudden reappearance of an adult son one last saw leaving for school at the age of nine must have been profoundly unsettling. ‘I was known to most people of the world by sight and by name, yet not to my mother,’20 Grant would say. He, in turn, would never know how ill she had been. Their subsequent relationship, unsurprisingly, might best be described as ‘difficult’.

Opinions differ as to how difficult the relationship actually was. Any references to mothers in his movies – no matter how slight or frivolously comic – have been pounced upon by some writers for their supposedly deeper ‘significance’: in one, for example, his character – a paediatrician – has written a book entitled What’s Wrong With Mothers.21 According to his biographers Charles Higham and Roy Moseley, there was never any real warmth or affection shared by mother and son; Elsie, it is claimed, was a ‘hard, unyielding woman’ who never showed much gratitude for her famous son’s regular flights to Bristol, nor did she allow him ‘to make her rich’, and she ‘remained stubbornly independent and uninterested in his film career till the end’.22 She was not, according to some accounts, a physically demonstrative person, and she could sometimes appear aloof and brusque in the presence of strangers.23 Dyan Cannon, Grant’s fourth wife, after spending some time with her new mother-in-law, described her as an ‘incredible’ woman with a ‘psyche that has the strength of a twenty-mule team’.24 Grant himself, after her death in 1973, two weeks short of her ninety-sixth birthday, admitted that he had often been exasperated and sometimes hurt by Elsie’s stubborn and misplaced sense of independence:

Even in her later years, she refused to acknowledge that I was supporting her … One time – it was before it became ecologically improper to do so – I took her some fur coats. I remember she said, ‘What do you want from me now?’ and I said, ‘It’s just because I love you,’ and she said something like, ‘Oh, you …’ She wouldn’t accept it.25

According to Maureen Donaldson, who lived with Grant for a brief period in the mid-seventies, he said that his mother ‘did not know how to give affection and she did not know how to receive it either’.26 He is said to have told one interviewer that his mother – in part because of her prolonged absence – had been, until quite late on, ‘a serious negative influence’ on his life.27 Bea Shaw, a friend of Grant’s, recalls him as being ‘devoted to his mother, but she made him nervous. He said, “When I go to see her, the minute I get to Bristol, I start clearing my throat.”’28

It seems, however, that the relationship was not as grim as some have suggested. Speaking in the early 1960s, when his mother was in her eighties, Grant described her as ‘very active, wiry and witty, and extremely good company’.29 According to some interviewers, Grant remembered visits to his mother when the two would talk and laugh together ‘until tears came into our eyes’.30 In a letter to the Bristol Evening Post, Leonard V. Blake recalled first seeing Elsie – ‘a rather plainly dressed woman’ – in a department store in the city, telling someone, ‘I have heard from Archie.’ Blake went on to observe that she ‘would visibly glow as his name was mentioned … I believe she would wander around Bristol just waiting to talk about Archie. He was the Sun to her.’31 Clarice Earl, who was a matron at Chesterfield Nursing Home in Bristol, where Elsie lived during her last few years, describes how when Elsie knew that her son was due to visit she would dress herself up and become excited: ‘She would sit by my office and look along the corridor toward the front door. When she saw him, she’d give a little skip and throw up her arms to greet him.’32 Years earlier, when the strangeness of her son’s celebrity was far fresher in her mind, she still showed much more interest in him and his career than has usually been suggested. Writing to him at the end of 1938, for example, she confessed: ‘I felt ever so confused after so many years you have grown such a man. I am more than delighted you have done so well. I trust in God you will keep well and strong.’33 After the end of the Second World War, when Elsie was almost seventy years old, she was interviewed by a Bristol newspaper about her son: ‘It’s been a long time since I have seen him,’ she said, ‘but he writes regularly and I see all his films. But I wish he would settle down and raise a family. That would be a great relief for me.’34