Полная версия

The Conversion of Europe

Here are two last sixth-century examples of the way in which locally prominent families could encourage and shape an emerging Christian character in the societies which looked to them for leadership. Samson was a native of Demetia, a kingdom of south Wales, who ended his life as a bishop in Gaul (later tradition would claim at Dol in Brittany). He was a part of that migration of British people from their own islands to the mainland of Gaul which transformed the province of Armorica into Brittany in the course of the fifth and sixth centuries. Samson is a somewhat shadowy figure, but his historical existence is attested to by the appearance of his name among a list of bishops who attended a church council held at Paris, probably in 561 or 562. It is assumed that his life fell within the first three-quarters of the sixth century. There exists a Vita Samsonis by an anonymous author which is difficult to date. The case for composition within about a century of its subject’s death is reasonably strong (though far from unassailable). The text will be used here, with caution, as a reliable source of evidence for at least the general outlines of Samson’s life.14

Samson was another, like Romanus or Emilian, taken by desire for the ascetic life. After receiving instruction from St Illtud at his monastery in Glamorgan, Samson sought a more arduous regime at a community recently founded on Caldey Island off the coast of what would later be called Pembrokeshire. Shortly after this, in the course of a visit to his family, Samson’s example seems to have persuaded most of its members to opt for the monastic life. As a family they took the plunge together: his mother and father, his five brothers, his paternal uncle with his wife and their three sons, and his aunt on the mother’s side. The family was a prominent one, ‘noble and distinguished as the world reckons these things’, in the words of Samson’s biographer. After the family’s conversion to monasticism they devoted all their property to the service of God; and there was plenty of it, ‘for they were the owners of many estates’. We know that they also built churches, because we are told that after he had become a bishop Samson consecrated them. Samson founded a monastery vaguely described as ‘near the river Severn’. He is said – in a section of the text which may be a later interpolation – to have travelled in Ireland, where he was given another monastery whose government he delegated to his uncle. Instructed in a vision that he must cross the sea and live as a peregrinus he sailed over to Cornwall, where he founded a further monastery. Continuing on his way he reached Brittany, where he established a monastery at Dol. Before his death he founded one more, apparently somewhere near the mouth of the river Seine.

The main lines of this account are credible. The commitment of this prominent family to a more intense form of Christian living was likely to have started ripples of influence which perhaps had effects, sadly hidden from us, within the churches which they built. Samson’s string of monastic foundations – and we shall see plenty more examples of such networks – had evangelizing potential. His journeys, foundations and miracles were associated by his biographer with conversion. In Cornwall, for example, in a district referred to as Tricurium, tentatively identified with the area formerly called Trigg in north Cornwall, Samson encountered people worshipping an idol. He admonished them, to little effect. Then it so happened that a boy was killed there in a riding accident. Samson pointed out that their idol could not revive the dead boy but that his God could; and would do so, provided that they promised to destroy their idol and for ever abandon its worship. They agreed to the bargain. Samson prayed for two hours, the boy returned to life, the idol was destroyed, and ‘Count Guedianus’ (? Gwythian) ordered all the people to be baptized by Samson. The holy man stayed in Cornwall for a little while longer, helpfully killing a serpent that was troubling the inhabitants and then founding his monastery, before resuming his journey to Brittany. The author of the Vita Samsonis had been to Cornwall and had seen ‘the sign of the cross which the holy Samson with his own hand had chiselled upon an upright stone’: the Cornish equivalent, we might think, of the creed written out by the hand of Gregory of Pontus in the cathedral of Neocaesarea. Samson’s travels in Trigg might be compared to Martin’s visit to Levroux.

Our last example takes us back to Gaul. Aredius was a slightly younger contemporary of Samson. A native of Limoges, he was born into a prominent family and as a young man was attached to the court of the Frankish King Theudebert (534–48). He was recruited by Bishop Nicetius of Trier – whom we shall meet again in a later chapter – under whom he studied and received the monastic tonsure. On the death of his father and brother he returned to the Limousin to look after his mother Pelagia, who had been left kinless and unprotected. Aredius dedicated himself and his property to the service of God, enthusiastically assisted by Pelagia. He built churches on his estates and founded a monastery at a place now named after him: Saint-Yrieix, a just recognizable derivative from Aredius, to the south of Limoges. The sick flocked to him and ‘he restored them to health by laying on of hands with the sign of the cross.’15

Gregory of Tours, our source for this, was a friend of Aredius and had good reason to be grateful to him. The church of St Martin at Tours was one of the principal beneficiaries of the will jointly made by Aredius and Pelagia in 572.16 It shows that the family was an extremely wealthy one, owning widespread estates, many of which came into the possession of the church of Tours: a further instance of pious largesse to set beside the examples quoted above of Remigius at Rheims and Bertram at Le Mans. Churches are mentioned at some of the estates. Although we cannot be certain that all of these had been built by Aredius, we can be reasonably sure of it in some instances, for example that of ‘our church dedicated in honour of St Médard [of Soissons] at Exidolium’, presumably Excideuil in northern Périgord, because Medard had died only some twenty years earlier and Aredius had been involved with the growth of his cult. The will also shows that Aredius and his mother possessed large amounts of ecclesiastical furnishings – embroidered linen and silk textiles (altar frontals, walland door-hangings), silver chalices and patens, and some very exotic items such as ‘the crown with a silver cross, gilded, with precious stones, full of relics of the saints … which crown has hanging from it eight leaves wrought from gold and gems’. It was presumably a votive, hanging crown, perhaps akin to the votive crown of the Spanish king Recesswinth (643–72) found in the treasure of Guarrázar, near Toledo. These textiles and treasures should alert us to the impact which the interiors of these churches might have made upon the senses of those who worshipped in them; a not insignificant element in considering the process of Christianization.

In the middle years of the sixth century John of Ephesus conducted an evangelizing campaign in the provinces of Asia, Caria, Lydia and Phrygia – roughly speaking, today’s western Turkey. In the course of several years’ work he and his helpers demolished temples and shrines, felled sacred trees, baptized 80,000 persons, built ninety-eight churches and founded twelve monasteries. And this was in the heart of the empire, an area where there had been a Christian presence since the time of St Paul, not in some out-of-the-way corner like Cornwall or Galicia. In 598 Pope Gregory wrote to the bishop of Terracina to express dismay at a report that had reached him to the effect that the inhabitants of those parts were worshipping sacred trees. Again, not a remote spot; Terracina is on the coast between Rome and Naples, its countryside traversed by the Via Appia, one of the busiest highways of the Mediterranean world.

These two reports remind us that the conversion and Christianization of the countryside was a very slow business. The point cannot be sufficiently emphasized. The evidence surveyed in this chapter has been largely normative, that is to say it lays out ideals or targets. Our sources speak with the official voice of the educated elite within the church; they do not describe the everyday reality of belief and observance among the laity. That reality will always be elusive. Can we make any assessment at all of what had been achieved? Any answer to this question must be cautious, but need not be blankly negative.

Our two earliest activists, Gregory of Pontus and Martin of Tours, were operating at times when and in places where Christianity had made no impact at all upon the countryside. We may guess that in this respect Pontus and Touraine were not untypical. Two centuries later, in the age of Gregory of Tours and Martin of Braga, conditions had changed. They were operating in a social world which was, in a formal sense, Christian. Paganism as overt, active, public cult no longer existed in Gaul or Spain (except among the Basques). Caesarius of Arles, Martin of Braga, Gregory of Tours, Pope Gregory the Great, had as their principal concern the problem of how to make people who were nominally Christian more thoroughly Christian, the more effectively to guard them from demonic assault which would threaten God’s protection of the whole community. These pastors were clear about the disposition and behaviour required of the good Christian and they did their utmost to set their standards and expectations clearly before the laity. Here, they are saying, is a pattern of godly behaviour to which you must try to conform. This is the message not just of the directly homiletic material (Caesarius, Martin) but also of much of what we are accustomed to think of as the ‘historical’ works of Gregory of Tours. They were also clear about what the good Christian should avoid. All four of these writers would probably have agreed in terming it rusticitas, ‘rusticity’. The notion of rusticity comprehended not just doing a bit of fencing or brushing your hair on a Sunday, not just boorish junketings at the Kalends of January, but potentially also something much more menacing in the guise of resort to alternative systems of explanation, propitiation and control. This is the lesson of the story about Aquilinus and the arioli. There existed an alternative network to the one presented by Christian teachers. There were other persons about, easily resorted to, claiming access to the means of explaining misfortune, curing sickness, stimulating love, wreaking vengeance, foretelling the future, advising when to undertake a journey, interpreting the flight of birds or the patterns on the shoulder-blades of sheep.

Historians have often written dismissively of ‘pagan survivals’, old beliefs and practices tolerated by a sagely easy-going church, which would subside harmlessly into the quaint and folkloric. But this is to miss the point. The men of the sixth century – and not just the sixth century by any means – were engaged in an urgent and a competitive enterprise. In a European countryside where over hundreds of years diverse rituals had evolved for coping with the forces of nature, Christian holy men had to show that they had access to more efficacious power. The element of competition emerges clearly in the tale of Aquilinus, or in the story about Samson and the Cornish boy killed in a fall from his horse: and, it may be said, in many others too. Competition involves an element of comparability, even of compromise. Thus there is scope for all sorts of nice questions about where and how to draw lines round the limits of the tolerable. Competition also involves the risk of overlapping perceptions of identity. How like to an ariolus was, say, Emilian or Friardus or Caluppa – in the eyes of contemporaries? Or in the eyes of historians?

Because this chapter has concentrated upon the period between the third and the sixth centuries the incautious reader might be left with the impression that the challenge of converting the countryside to Christianity was one that was faced and surmounted during that period. Not so. A start had been made; but the operation was one which would continue to tax the energies of bishops for centuries to come. Country people are notoriously conservative. We may be absolutely certain that more than a few generations of episcopal exhortation or lordly harassment would be needed to alter habits inherited from time out of mind. Ways of doing things, ways that grindingly poor people living at subsistence level had devised for managing their visible and invisible environments, were not going to yield easily, perhaps were not going to yield at all, to ecclesiastical injunction. But even granite will be dented by water that never ceases to drip. This is one way in which ’something will start to happen’. If there were country churches (as in Touraine), and if there were clergy to serve them (a big ‘if’, that one), and if the laity attended church (a practice for which we have only sporadic evidence) – would the people then become more Christian? The question mark stays in place because at this point a spectre rises to haunt us, the most troubling of the problems laid out in Chapter 1: what makes a Christian? Did Martin ‘make Christians’ by smashing a temple at Levroux? Sulpicius Severus thought so. Were the lakeside dwellers of Javols ‘made Christian’ when they diverted their offerings of local produce from lake to church? Gregory of Tours thought so. Did Samson ‘make Christian’ the people of Trigg by raising a boy from the dead and killing a snake? Count Guedianus thought so, if Samson’s anonymous biographer is to be believed, for he ordered them all to be baptized. This is what our sources tell us; we have to make of it what we can.

CHAPTER THREE

Beyond the Imperial Frontiers

Fish say, they have their Stream and Pond;

But is there anything Beyond?

RUPERT BROOKE, ‘Heaven’, 1914

IN THE LATE ANTIQUE PERIOD, as we saw in Chapter 1, it was standard practice for Christian communities which had put down roots outside the frontiers of the Roman empire to be provided with bishops on request. To Patrophilus, bishop of Pithyonta in Georgia, who attended the council of Nicaea in 325 (see above p. 26) we can add others. There was Frumentius, for example, consecrated by Athanasius of Alexandria, author of the Life of St Antony, in about 350 as the bishop of a Christian community based at Axum in Ethiopia. There was Theophilus ‘the Indian’, apparently a native of Socotra in the Gulf of Aden, who was sent at much the same time to be the bishop of Christian communities in southern Arabia which seem to have originated as trading settlements. Patrophilus, Frumentius and Theophilus operated far to the east or south of the Roman empire. They are shadowy figures who have left but the faintest of traces. Most scholars, however, are agreed that they did exist and that they are witnesses to the flourishing of some very far-flung branches of the Christian church. They had western counterparts, marginally better documented, beyond the imperial provinces of the fourth and fifth centuries, who are the subject of this chapter. Among the earliest of them known to us was a man named Ulfila – or Wulfila, or Ulfilas; it is variously spelt. His name was Germanic and means ‘Little Wolf’ or ‘Wolf Cub’. Much later, he would come to be known as ‘the Apostle of the Goths’. This is not quite what he was, though his achievements were remarkable enough. To provide him with a background and a context we must go back for a moment to third-century Pontus and to Bishop Gregory the Wonder-worker.

The Canonical Letter of Gregory the Wonder-worker (above p. 35) was prompted by a crisis in the provinces of northern Asia Minor in the middle years of the third century. Upon this sleepy corner of the empire there had unexpectedly fallen the cataclysmic visitation of barbarian attack. Goths settled on the north-western shores of the Euxine (or Black) Sea had managed to requisition ships from the Hellenistic sea ports – such places, presumably, as Chersonesus (Sevastopol) in the Crimea – which enabled them to raid the vulnerable coastline of Asia Minor. The earliest raids took place in the mid-250s. The invaders came to pillage, not to settle. In their eyes human booty was as desirable as temple treasures or the jewel-cases of rich ladies; captives, some of whom might buy their release, others of whom would be carried off into a life of slavery. In the wake of these devastations and collapse of order Bishop Gregory was approached by a colleague, possibly the bishop of Trapezus (Trebizond), and invited to pronounce on the disciplinary issues which arose from the conduct of the Christian provincials during the disturbances. His reply has come down to us because its rulings came to be regarded as authoritative and were incorporated into the canon law of the eastern or Orthodox branch of the church.1

Gregory’s letter casts a shaft of light upon the human misery and depravity occasioned by the raids as well as upon the responsibilities assumed by a bishop in trying to pick up the pieces of shattered local life in their wake. Had captives been polluted by eating food provided for them by the barbarians? No; for ‘it is agreed by everyone’ – Gregory had evidently made enquiries – ‘that the barbarians who overran our regions did not sacrifice [food] to idols.’ Women who had been the innocent victims of rape were guiltless, following the precepts of Deuteronomy xxii.26–7: ‘But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing … for he found her in the field, and the damsel cried, and there was none to save her.’ It was different, however, noted the bishop, with women whose past life had shown them to be of a flighty disposition: ‘then clearly the state of fornication is suspect even in a time of captivity; and one ought not readily to share in one’s prayers with such women.’ One can only speculate about the grim consequences of this ruling in the tight little communities of the towns and villages of Pontus. Gregory’s sense of outrage is vividly conveyed across the seventeen centuries that separate him from us. Prisoners of the Goths who, ‘forgetting that they were men of Pontus, and Christians’, directed their captors to properties which could be looted, must be excommunicated. Roman citizens, ‘men impious and hateful to God’, have themselves taken part in looting. They have ‘become Goths to others’ by appropriating booty taken but abandoned by the raiders. It was ‘something quite unbelievable’, but they have ‘reached such a point of cruelty and inhumanity’ as to enslave prisoners who had succeeded in escaping from their barbarian captors. They have used the cover of disorder to prosecute private feuds. They have demanded rewards for restoring property to its rightful owners. Gregory commended to his correspondent the measures which he had taken in his own diocese: enquiries, hearing public denunciations, setting up tribunals (‘the assembly of the saints’) and punishments meted out in accordance with the extremely severe penitential discipline of the early church. There are parallels here with the fate of all later actual or suspected collaborationists. Many, however, were beyond the reach of Gregory’s ministrations. These were the captives who did not escape, who were not wealthy enough to buy their freedom, who were of insufficient status to command a ransom payment from kinsfolk or neighbours left at home. Borne offinto slavery among barbarians, the captives took with them the solace of their Christian faith. In this fashion little pockets of Christianity struck root among the Goths outside the frontiers of the empire.

The Goths matter to us because their crossing of the Danube frontier in 376 and subsequent settlement inside the empire symbolize the beginning of the process which since the time of Edward Gibbon we have known as the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Who were these barbarians?

Those whom Roman writers of the third and fourth centuries referred to as Goths were a variety of peoples who spoke a Germanic language, Gothic. Known to the Romans in the first century A.D., they were then living in the basin of the lower Vistula in what is now Poland. They migrated thence in a south-easterly direction towards the Ukraine in the latter part of the second century. At the time of the raids on Asia Minor they were settled most thickly in the lower valleys of the Dnieper and the Dniester. Some among them were expanding to the south-west, into what is now northern Romania. This brought them into proximity with the only province of the Roman empire which lay to the north of the Danube, namely Dacia; an area bounded on the south by the Danube between the Iron Gates and its confluence with the river Olt, spreading northwards to take in the uplands of Transylvania embraced by the Carpathian mountains. During the troubled middle years of the third century the Goths pressed hard on the frontiers of Dacia and launched raids into Thrace and even Greece. It was to some degree in response to this pressure that the Emperor Aurelian withdrew Roman rule from Dacia in the early 270s. Thenceforward this sector of the empire’s frontier lay along the Danube. The Goths moved into the abandoned but by no means deserted province. Dacia had experienced a century and a half of Romanization. Substantial elements of the Romano-Dacian population remained, and archaeological evidence suggests that a modest urban life with a modest villa economy to supply its needs limped along into the Gothic period. It is possible, though unproven, that there were Christian communities among the population of Dacia in the third century. The most extraordinary witness to the tenacity of Roman civilization is the survival there of the Latin language, the ancestor of modern Romanian.

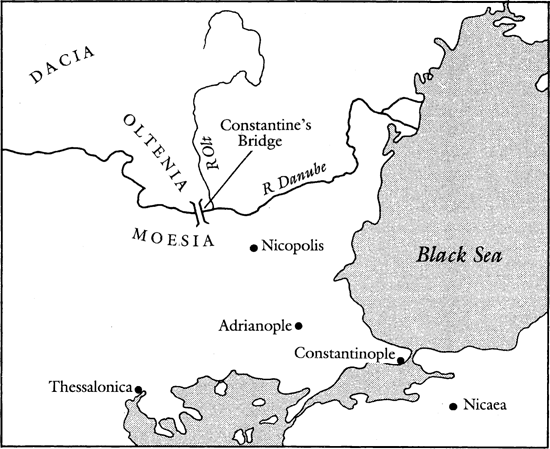

3. To illustrate the activities of Ulfila during the fourth century.

Much has been revealed about Gothic culture in this period by the archaeologists. To the evidence of the so-called Sîntana de Mureş/Černjachov culture, so named from sites respectively in Transylvania and the Ukraine, may be added a little information from Roman writers. What these combined sources have to tell us is as follows. The Goths were settled agriculturalists who practised both arable and pastoral farming. They lived in substantial villages but not in towns. Their houses were of wood, wattle-and-daub and thatch; sometimes they had stone footings or floors. Traceable artefacts are pottery, wheel-thrown, of good quality clay; iron tools and weapons; buckles and brooches of bronze or silver; and objects made of bone such as combs. These artefacts, commonplace enough in themselves, suggest a degree of specialization and division of labour. The Goths disposed of their dead by both cremation and inhumation, and the remains were frequently though not always accompanied by grave-goods. Variations in quantity and quality of personal possessions (in graves), and in the size of dwellings, suggest communities wherein were marked differences of wealth and status. A few hazardous inferences about the religious beliefs of the Goths may be essayed by the imprudent on the basis of the archaeological materials. The written sources tell us of sacrificial meat – if not among raiding parties in Asia Minor – and of wooden images or idols. We hear of a war god and of seasonal festivals. Gothic political organization is scarcely documented at all, and therefore fiercely controversial among scholars. However, it is likely that among the group of Goths settled to the west of the Dniester and termed by a Roman contemporary the Tervingi there existed in the fourth century a hereditary monarchy and a nobility of tribal chieftains. The Goths cannot be said to have had a written culture, though they did possess a runic alphabet. Runic inscriptions have been found on some grave-goods and, most famously and enigmatically, on a great gold torque, or neck ring, found in the treasure of Pietroasa in Romania, unearthed in 1837. Finally, we must observe that their interactions with the Roman world across the Danube were close and not always hostile. Goths left their native land to serve in the imperial armies, sometimes rising to high rank. Large amounts of Roman coin circulated in Gothia. Archaeologists have found remains of the tall, narrow Mediterranean pots called amphorae in Gothic contexts: they were used for the transport of wine or oil, commodities more likely to be trade goods than plunder.