Полная версия

The Conversion of Europe

In sum, the Goths were in no sense ‘primitive’ peoples. The Tervingi in Dacia (who are our main concern) were neighbours of the Romans, living in a Romanized province, with Roman provincials – whether native or captive – living under their rule. On the periphery of the Roman world, they experienced cultural interactions with their imposing neighbour. Like all the other Germanic barbarian peoples, the Goths in peacetime found much to admire, to envy and to imitate in Roman ways. When the pressure of Roman might bore down on them too heavily, they defended themselves by adopting those political and military usages which they had correctly identified as buttressing Roman imperial hegemony. It is a familiar pattern: peripheral outsiders tend to model themselves upon the hegemonic power on whose flanks they are situated. When the defences of the Roman empire gave way the Germanic barbarians entered upon an inheritance for which they had long been preparing themselves. They came not to wreck but to join. In this manner the decline and fall of the western empire was to be not destruction but dismemberment, a sharing out of working parts under new management.

Matters did not present themselves in such a rosy light to the provincials who lived to the south of the Danube in closest proximity to the Tervingi in the fourth century; nor to the imperial government whose job it was to protect them. Although there would seem to have been uneasy peace for a generation or so after the Gothic settlement in Dacia, pressure on the imperial borders started up again during the first quarter of the new century. The lower Danube frontier was impressively defended. There was a string of forts along the southern bank whose garrisons numbered at least 60,000 men. Detachments of the imperial fleet regularly patrolled the river. There were arms and clothing factories a little way behind the frontier to supply the troops. A spirit of invention and experiment is attested to by a curious anonymous work from this period and, quite possibly, this region which sought government sponsorship for, among other things, a paddledriven warship powered by oxen, a piece of mobile field-artillery, a portable bridge made of inflated skins and a new and improved version of the scythed chariot drawn by mail-clad horses. In the 320s Constantine built a colossal bridge over the Danube – it was 2,437 metres long – a little above its confluence with the Olt and used it to reoccupy Oltenia, the land in the angle between the two rivers. From this base a campaign was mounted against the Tervingi in 332. It was completely successful: the Tervingi were defeated and reduced to client status, their ruler’s son carried off to Constantinople as a hostage. This peace lasted for thirty-five years with only small-scale violations, notably in the late 340s. In the 360s it broke down, and the Emperor Valens fought a less decisive war in the years 367–9 which brought about a further pacification. There matters rested until the arrival on the scene shortly afterwards of a terrifying new enemy, the Huns.

The Huns changed the terms of Romano-Gothic relations for ever. A nomadic people from central Asia, wonderfully skilled with horse, bow and lassoo and with a reputation as pitiless enemies, they began to move westwards – no one really knows why – in the second half of the fourth century. In the early 370s they collided with the Greuthingi, the eastern group of Goths settled between the Dniester and the Dnieper. The Greuthingi were defeated, the survivors among them enslaved. In the wake of these events the Tervingi sought asylum within the Roman empire. Reluctantly, Valens agreed to this request. In 376 the Tervingi crossed the Danube on to imperial territory. Relations between Goths and Romans broke down in the following year when the imperial government failed to keep its promises about supplying foodstuffs to the refugees. War followed in 378. A decisive battle was fought near Adrianople in August; the Roman army was defeated and the Emperor Valens killed at the hands of the Tervingi under their leader Fritigern. There ensued four years of confusion during which the Goths failed to take Constantinople and pillaged Thrace. In 382 a settlement was reached with the new emperor, Theodosius I: Fritigern and his followers were permitted to settle peacefully in the province of Moesia, south of the Danube and just west of the Black Sea. There they remained until 395 when a new leader, Alaric, would start the Goths on further travels which would take them to Italy, where they would sack Rome in 410; then to Aquitaine, where they were again settled under treaty arrangements in 418; and finally to Spain, where the Gothic monarchy would flourish until overthrown by the forces of Islam early in the eighth century.

Among those who were carried off into permanent captivity in the course of the Gothic raids into Pontus in the middle of the third century were the ancestors of Ulfila. The family evidently retained a memory of its origins. Ulfila knew that his ancestors had lived in a village called Sadagolthina, near Parnassus in Cappadocia, about fifty miles south of modern Ankara. (This is at least 150 miles from the nearest point on the Black Sea coast: it shows how far inland the Gothic raiders had penetrated and explains something of the terror they inspired.) We know too that this band of displaced persons in Gothia not only retained but also diffused their faith. ‘They converted many of the barbarians to the way of piety and persuaded them to adopt the Christian faith,’ tells the fifth-century historian Philostorgius, one of the principal sources for what little we know of Ulfila. It may be that the family intermarried with Goths; so much is suggested by Ulfila’s Gothic name: we do not know. Indeed, it must be stressed that we know absolutely nothing whatsoever about the conditions in which captives and their descendants lived among the Goths. This is one of several areas of puzzlement and uncertainty which necessarily render our understanding of Ulfila so hazy. Another concerns his education. Ulfila had been ‘carefully instructed’, recorded his pupil Auxentius. He was fluent in Greek, Latin and Gothic, in all three of which languages he composed ‘several tractates and many interpretations’. His translation of the Bible into Gothic was a towering intellectual achievement. In the world of late antiquity education to anything beyond the most elementary level was only for the rich, or those who could find a rich patron. How and where did Ulfila get his education? We have not the remotest idea.

At the age of thirty, when he had attained the rank of lector or reader, one of the minor orders of the church, Ulfila was sent to Constantinople by the ruler of the Tervingi as a member of a diplomatic mission. This would have been in about 340 or 341, some years after the peace of 332. The imperial throne was now occupied by Constantius II (337–61), son of the great Constantine. Again, we wonder why Ulfila was chosen to serve in this capacity. While in Constantinople he was consecrated a bishop by the patriarch. (There are formidable difficulties about the date of his consecration, which I here pass over.) His commission was to be ‘bishop of the Christians in the Gothic land’; to serve, that is, an existing Christian community – by whom indeed his episcopal consecration had presumably been requested – not to undertake specifically missionary activities.

His episcopate ‘in the Gothic land’ lasted for seven years, which takes us to 347/8. At the end of this period the ‘impious and sacrilegious’ (but unnamed) ruler of the Tervingi initiated ‘a tyrannical and fearsome persecution’ of the Christians under his rule. Ulfila evidently judged that discretion was the better part of valour and led a large body of refugee Christians across the Danube and into asylum on Roman soil. Welcomed by the authorities with honour and respect, Ulfila and his flock received from the emperor land on which to settle near the city of Nicopolis (Veliko Tǔrnovo in the north of modern Bulgaria), some thirty miles south of the frontier in the province of Moesia Inferior. We are told that Constantius held Ulfila ‘in the highest esteem’ and would often refer to him as ‘the Moses of our time’ because through him God had liberated the Christians of Dacia from barbarian captivity.

Ulfila spent the rest of his life at Nicopolis, ministering to his congregations, studying, teaching, translating the Bible. He was also drawn into the principal theological controversy of the day, the Trinitarian debate arising from the teachings of the Alexandrian priest Arius (d. 336). Arianism was the doctrine that the Son of God was created by the Father. Its opponents, who claimed the name of Catholic which literally means ‘general’ or ‘universal’ – taught that Father, Son and Holy Spirit were co-eternal and equal in Godhead. To put this in another way, Arius sought to avoid any dilution of monotheism by stressing the indivisibility, the majestic one-ness and omnipotence of God, and the subordination to Him of the Son. To those not attuned to theological debate, the relationship between the three Persons of the Trinity is an unrewarding topic. We must accept, first, that it was long and keenly debated in the fourth century and that it nourished some of the finest minds of the age. Second, we should bear in mind that at the time – whatever the dispute might have been made to look like by later commentators – it was not a simple matter of a straight fight between orthodoxy and heresy. Trinitarian orthodoxy was not something given, like the doctrines of the Resurrection or the Ascension. It was in the process of being hammered out by recourse to difficult scriptural texts which could yield diverse interpretations. The problem was to find a doctrinal formula which would satisfy several different theological factions. Third, the debate was one which necessarily had a political dimension. With the arrival on the scene of imperial patronage of the Christian church, theological controversy could no longer be simply a matter of intellectual debate. What was now also at stake was access to huge and unprecedented material resources, legal privileges and influence at the imperial court. The penalties of finding yourself on the losing side were therefore substantial. Constantine, having once publicly associated himself with Christianity, had taken an assertive if not always instructed role in ecclesiastical controversy. He it was who had summoned and presided over the council of Nicaea in 325, the first major attempt to find a doctrinal formulation which would be widely acceptable; the Nicene creed was the result. This settlement of the dispute held the field, though not unchallenged, until Constantine’s death in 337. But his son Constantius favoured the Arian tendency and under his patronage successive councils – Antioch in 341, Sirmium in 351, Rimini in 359, Constantinople in 360 – drafted credal statements which, though necessarily in the circumstances somewhat fudgy, leant away from the Nicene position towards the Arian one. Ulfila was consecrated a bishop by one of the leading spirits of this ‘court Arianism’, attended the council of Constantinople in 360 and was on close terms with an emperor who was widely held to be sympathetic to Arianism. The successor of Constantius in the eastern half of the empire, after the brief resign of Julian the Apostate (361–3), was Valens (364–78), who proved another protector of the Arians. One fifth-century historian, Sozomen, tells us that Ulfila was chosen to head the embassy to Valens which sought permission for the Tervingi to enter the empire in 376. If true, this report would suggest that Ulfila had contrived to maintain the connections with the imperial court which he had enjoyed in the time of Constantius. But the tide was turning against the moderately Arian or non-Nicene party. The Emperor Theodosius I (379–95) was an unswerving partisan of the doctrinal formulations of Nicaea. Decrees enjoining the acceptance of the Nicene creed were issued in 380. In the following year Arian churches were confiscated and handed over to the Catholics, and all meetings of the heretics were banned. The last glimpse we have of Ulfila is in 383, travelling to Constantinople to attend another church council in the company of two Danubian bishops, deposed for Arianism, whose cause he was going to plead with the emperor. He died in Constantinople shortly afterwards.

The main reason why we know so little of Ulfila lies in the victory, never to be reversed, of Nicene orthodoxy in official circles in his last years. It is a good example of the adage that history is written by the victors. The memory of Arius and his followers was systematically vilified, their writings hunted down and destroyed. Ulfila was too big to be ignored; but he could be, and was, belittled. Had the moderateArian creed to which he adhered come out on top, Ulfila would be remembered as one of the giants of the fourth-century church. As it is, we have to struggle with fragmentary and ambiguous texts to discern even the shadowy outline of a notable career.

What then was the significance of Ulfila? He was not a missionary in the generally accepted sense of the word. He did not go off to live among a heathen people in order to convert them to Christianity. Instead, he went as the bishop of an existing Christian community beyond the imperial frontier, a community which no doubt included persons of Gothic birth but which was principally composed of displaced foreigners living under Gothic rule. We need not doubt that this community made converts among the Goths in Ulfila’s day as it had done before; but conversion of the heathen was not perceived as its prime function. The Christians in Gothia were, in Gibbon’s words, ‘involuntary missionaries’.2

Ulfila was almost certainly not the first churchman to have been sent to serve Christian communities among the Goths beyond the imperial frontiers. Among the bishops who attended the council of Nicaea in 325 was a certain Theophilus ‘of Gothia’; it has been conjectured that he ministered to Christian communities among the Goths settled in the Crimea. A letter of St Basil of Cappadocia written in about 375 refers to a certain Eutyches, who had evidently lived at some time past but of whom nothing further is known, in terms which suggest ministry in Gothic lands. However, as we have already seen in the course of discussion in Chapter 1, there was at that period no sense that it was the duty of the Romano-Christian world to evangelize pagan barbarians beyond its borders. Christianity was not for outsiders. So we are told: yet the question may be probed a little further. The adhesion of Constantine to Christianity was followed by an ever more strident and assertive trend towards the near-identification of empire and church. Christianity thus became a part of the empire’s cultural armoury. Did it occur to the imperial establishment of the fourth century, as it would in later centuries, that the faith could be used to tame threatening barbarians in their homelands? We do not know, but it looks as though the Goths thought so. Each of the two known outbreaks of anti-Christian persecution by the Gothic authorities in the fourth century coincided with periods of military hostilities between Goth and Roman. The first of these was in 347–8, when Ulfila left Gothia to cross the Danube and settle at Nicopolis. The second came in the wake of Valens’ Gothic war of 367–9. We are rather well informed about it owing to the survival of an account of the sufferings of a Gothic martyr, Saba, who perished on 12 April 372. A recent authority has commented that ‘the Goths would seem to have been afraid that Christianity would undermine that part of Gothic identity which was founded in their common inherited beliefs, so that religion was not just an individual spiritual concern, but also a political issue standing in some relation to GothoRoman affairs.’3

All of which prompts further speculation about the role of Ulfila. His relations with the imperial Christian establishment were close: he was consecrated a bishop in Constantinople, given land near Nicopolis by his admirer Constantius, attended councils within the empire, was apparently confident of his intercessory powers with Theodosius I. It is impossible not to reflect that when he returned to the empire in 347–8 Ulfila must have been in a position to furnish the government with a good deal of useful intelligence concerning goings-on in Gothia: possibly on other occasions too. Does this mean that in going to Gothia as a bishop Ulfila was undertaking what has been called an ‘imperially-sponsored mission’? That is perhaps to go too far. Ulfila was not a Roman agent. We must remember that he was so far trusted by the Gothic authorities as to be commissioned to negotiate on their behalf on two occasions that we know of, possibly on others of which we are ignorant. Ulfila faced both ways. Missionary or quasi-missionary churchmen often do.

It is entirely appropriate, in the light of this, that his most enduring achievement should have been the translation of the Bible into Gothic, giving to his people, or his people by adoption, the holy writings of the Roman faith in their own Germanic tongue. Here is Philostorgius again: ‘He was the inventor for them of their own letters, and translated all the Scriptures into their language – with the exception, that is, of the books of Kings. This was because these books contain the history of wars, while the Gothic people, being lovers of war, were in need of something to restrain their passion for fighting rather than to incite them to it.’ Ulfila was not the first to undertake biblical translation; the so-called ‘Old Latin’ and Syriac versions were already in circulation. But these were existing literary languages current within the Roman empire. To no one had the notion occurred of translating the scriptures into a barbarian tongue which had never been written down before. Perhaps, as is often the case with simple but revolutionary and liberating ideas, it could only have come to one who was himself in some sense an outsider.

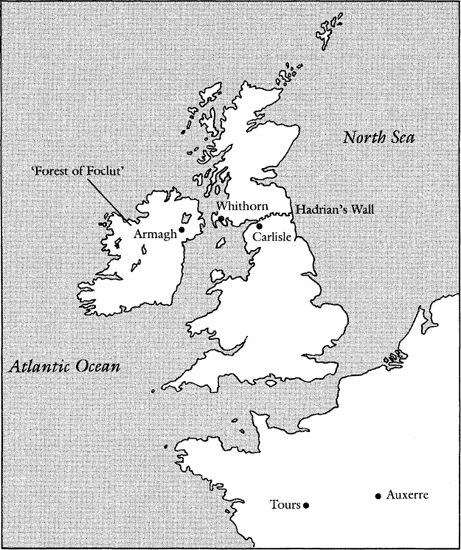

4. To illustrate the activities of Ninian and Patrick in the fifth century.

If we now direct our attention to the western extremities of the empire at a time a couple of generations or so after Ulfila’s day we shall meet two further instances of the same phenomenon, the sending of bishops to existing Christian communities outside the imperial frontier. We shall also encounter something altogether unexpected in a late-antique context: a churchman who experienced a missionary vocation to take the faith to heathen barbarians and who has left a precious account of how he came to engage himself in such an eccentric activity.

Our first instance is a very shadowy one, about whom we know far less than we do about Ulfila. Ninian, or Nynia, was the name of a British bishop sent to minister to a community of Christians in what is now Galloway in the south-west of Scotland. His episcopate is most probably to be placed somewhere in the middle years of the fifth century. By this time the Roman provinces of Britain were no longer part of the empire. As with Dacia in the 270s, so in 410 the government of the Emperor Honorius had taken the decision to withdraw the apparatus of Roman rule from Britain. It is unlikely that contemporaries imagined that this state of affairs would be permanent; both the imperial government and the British provincials probably anticipated that at some stage in the future, when times were easier, Roman control would be reimposed. Meanwhile, life in Britain seems to have gone on in much the same way until well into the fifth century.

Galloway was within reach, by way of the easily navigable Solway Firth, of the contiguous parts of what had been Roman Britain: the town of Lugubalium (Carlisle), the forts of the Cumbrian coast, and the farms of the Eden valley. A scatter of small finds – coins, pottery – of Romano-British material in south-western Scotland indicates that connections were established. How a Christian community grew up there we have no means of knowing, but that one was in existence by the fifth century is certain. It is attested by the so-called ‘Latinus’ stone at Whithorn, datable to c. 450, whose enigmatic Latin inscription may record – the latest suggestion by a leading authority – the foundation of a Christian church there by a man named Latinus.4 We have a context for Bishop Ninian. We might also have the names of two of his successors. Some twenty miles west of Whithorn, at Kirkmadrine in the Rhinns of Galloway, another inscribed stone, possibly of the early sixth century, commemorates ‘the holy and outstanding sacerdotes Viventius and Mavorius’. (Sacerdotes could mean either ‘priests’ or ‘bishops’: in the Latin of that period the second meaning was more common than the first.)

Ninian himself is not mentioned by name until the eighth century, when Bede devoted two passing sentences to him in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede was, as I have said in Chapter 1, a very conscientious scholar who in this instance dutifully reported what he had heard from persons whom he regarded as reliable sources. Among them was quite probably the English Bishop Pehthelm of the recently revived see of Whithorn. However, Bede was careful to qualify his report with a hint of uncertainty: ‘as they say’. What Bede had been told was that Ninian was a Briton who had received religious instruction at Rome, had gone as a bishop to Whithorn, where he had built a church of stone dedicated to St Martin of Tours, had converted the southern Picts to Christianity and had on his death been buried at Whithorn. This report presents all sorts of difficulties. It is generally though not universally agreed that some of what Bede tells us is more likely to represent what the eighth century wanted to believe about Ninian than any historical reality. As we shall see in due course, the eighth century was more interested in Roman connections and missions to barbarians than was the fifth. It may not be irrelevant that Bishop Pehthelm was a correspondent of the great St Boniface, strenuous upholder of Roman direction of the church’s overriding duty of mission to pagan barbarian peoples. All that is reasonably certain is that a Christian community had grown up beyond the imperial frontier in Britain and that Ninian had been appointed its bishop.

Our second instance of a bishop sent beyond the western extremities of the empire is a mite less shadowy. The contemporary chronicler named Prosper of Aquitaine – he whose De Vocatione Omnium Gentium occupied us briefly in Chapter 1 – informs us in his annal for the year 431 that (in his own words) ‘Palladius, consecrated by Pope Celestine, is sent as their first bishop to the Irish believers in Christ.’ Here at last is some ‘hard’ information. Prosper had visited Rome in that very year, 431, to consult Pope Celestine on a matter of theological controversy. He could even have met Palladius on the occasion of the latter’s visit to Rome for episcopal consecration. We may be as certain as we can be of anything in this period that in the year 431 an Irish Christian community received Palladius as its first bishop.

Ireland, notoriously, had never formed a part of the Roman empire. But as with Gothia or Galloway there was a degree of cultural interaction between Ireland and the neighbouring provinces which may plausibly be invoked in an investigation of Irish Christian origins. There were trading relations of long standing between Britain and Ireland. As long ago as the first century Tacitus could observe in his memoir of his father-in-law Agricola that Ireland’s harbours were known to the Roman forces in Britain ‘through trading and merchants’. A variety of artefacts provides archaeological confirmation of lively commerce between eastern and southern Ireland and her neighbours to the east, Britain and quite possibly Gaul too, throughout the Roman period and beyond. Irish mercenaries served in the Roman army in Britain. Refugees from Britain sought asylum in Ireland. Pirates from Ireland were raiding the western seaboard of Britain from the third century onwards, for the same reasons that Ukrainian Goths were striking deep into Asia Minor. Forts such as those at Cardiff, Caer Gybi on Anglesey, Lancaster and Ravenglass were built to protect civilian Britain from these predators. In 367 an unprecedented alliance of Irish, Picts (from Scotland) and Saxons (from north Germany) overcame the defences of Britain and plundered the provinces for nearly two years. A chieftain remembered in Irish legend as Niall Noígiallach, Niall ‘of the Nine Hostages’, was raiding Britain in the late fourth century.