Полная версия

The Conversion of Europe

You should remove all pollution of idols from your properties and cast out the whole error of paganism from your fields. For it is not right that you, who have Christ in your hearts, should have Antichrist in your houses, that your men should honour the devil in his shrines while you pray to God in church. And let no one think he is excused by saying: ‘I did not order this, I did not command it.’ Whoever knows that sacrilege takes place on his estate and does not forbid it, in a sense orders it. By keeping silence and not reproving the man who sacrifices, he lends his consent. For the blessed apostle states that not only those who do sinful acts are guilty, but also those who consent to the act [Romans i.32]. You therefore, brother, when you observe your peasant sacrificing and do not forbid the offering, sin, because even if you did not assist the sacrifice yourself you gave permission for it.4

Constantinople, Africa, Italy – and other places too: wherever we look, bishops were encouraging the landed elites, the people who commanded local influence, to take firm and if necessary coercive action to make the peasantry Christian – in some sense. Other bishops took matters into their own hands, choosing to take direct and personal action rather than confining themselves to exhortation. The most famous example of such an activist is Martin, bishop of Tours from about 371 until his death in 397.

Martin is a man of whom we can know a fair amount, principally owing to the survival of a body of writings about him by his disciple Sulpicius Severus. Sulpicius was just the sort of man whom Augustine, John Chrysostom and Maximus of Turin were trying to reach and influence. He was a rich, devout landowner with estates in southern Gaul. Inspired by Martin’s ideals Sulpicius founded a Christian community at one of his estates, Primuliacum (unidentified; possibly in the Agenais), and it was there that he composed his Martinian writings. These comprise the Vita Sancti Martini (Life of the Holy Martin), composed during its subject’s lifetime, probably in 394–5; three Epistulae (Letters) from 397–8; and two Dialogi (Dialogues) from 404–6 also devoted to Martin.5 The Vita was the first work of Latin hagiography to be composed in western Christendom: it displays literary debts to the Vita Antonii by Athanasius and it was in its turn to be enormously influential during the coming centuries as a model of Christian biography. Sulpicius presented Martin as a vir Deo plenus, ‘a man filled with God’. Sulpicius’ Martin was first and last a spiritual force – a man who walked with God, a man set apart by his austerity and asceticism, a monk who was also active in the world as a bishop, fearless in his encounters with evil, endowed with powers beyond the natural and the normal, worthy to be ranked with prophets, apostles, martyrs: a powerhouse of holy energy which crackled across the countryside of Touraine.

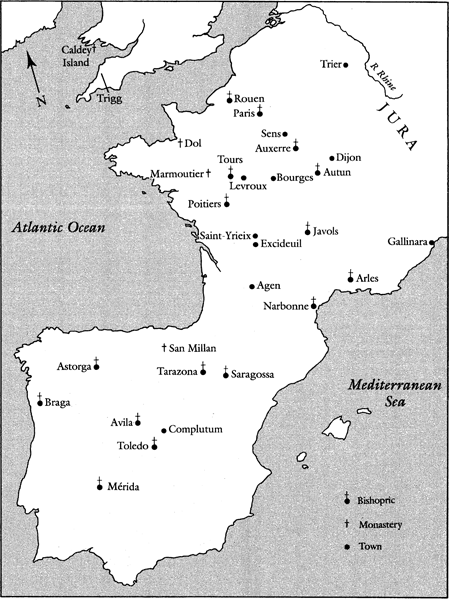

One of the features of Sulpicius’ writings about Martin which strikes the reader is their defensive and apologetic tone (to be distinguished from the didacticism common to all hagiography). Martin was a figure of controversy during his lifetime and continued to be controversial after his death. This was in large part because he was in more ways than one an outsider. In the first place he was not a native of Gaul. He was born, probably in 336, at Sabaria in the province of Pannonia (now Szombathely in Hungary, not far from the Austro-Hungarian border) and he was brought up in Italy, at Pavia. He was of undistinguished birth, the child of a soldier. As the son of a veteran Martin was drafted into the army as a young man (351?) and served in it for five years. A convert to Christianity as a child, he was baptized in 354. After obtaining a discharge from the army in 356 he returned to Italy, where he lived for a period as a hermit with a priest for companion on the island of Gallinara off the Ligurian coast to the west of Genoa. Making his way back to Gaul he attached himself to Bishop Hilary of Poitiers, a churchman whose enforced residence in the east between 356 and 360 – exile during the Arian controversy (for which see Chapter 3) – had borne fruit in acquainting him with eastern monastic practices. Martin settled down as a hermit at Ligugé outside Poitiers. His fame as a holy man spread widely in the course of the next decade and in 371 (probably) he was chosen by the Christian community of Tours as their bishop.

2. To illustrate the activities of Martin, Emilian and Samson, from the fourth to the sixth centuries.

Martin’s pre-episcopal career was extremely unconventional. Of obscure origin and mean education, tainted by a career as a common soldier, ill-dressed, unkempt, practising unfamiliar forms of devotion under the patronage of a bishop himself somewhat turbulent and unconventional, the while occupying no regular position in the functioning hierarchy of the church – at every point he contrasted with the average Gallic bishop of his day, who tended to be well heeled, well connected, well read and well groomed. No wonder that the bishops summoned to consecrate Martin to the see of Tours were reluctant to do so. No wonder that Martin did not care to associate with his episcopal colleagues.

This was not the only way in which Martin’s behaviour continued unconventional after he had become a bishop. He refused to sit on an episcopal throne. He rode a donkey, rather than the horse which would have been fitting to a bishop’s dignity. He dressed like a peasant. He founded a monastery at Marmoutier, not far from Tours, where he lived with his disciples, rather than in the bishop’s house next to the cathedral in the city. He was no respecter of persons. He insisted on forcing his way into the house of Count Avitianus in the small hours of the night to plead for the release of some prisoners. When dining with the usurping Emperor Magnus Maximus he was offered the singular honour of sharing the emperor’s goblet of wine; instead of handing it back to Maximus, Martin passed it on to a priest who was accompanying him. His pastoral activities, to which we shall return shortly, were most peculiar. He frequently encountered supernatural beings: the Devil, several times, once masquerading as Christ (but Martin saw through him); angels, demons, St Mary, St Agnes, St Thecla, St Peter and St Paul. He had telepathic powers, could predict the future, could exorcize evil spirits from humans or animals and could raise the dead to life. He worked many miracles and wonders, conscientiously chronicled by Sulpicius Severus. His fame spread widely. He was called over to the region of Sens to deliver a certain district from hailstorms through the agency of his prayers. An Egyptian merchant who was not even a Christian was saved from a storm at sea by calling on ‘the God of Martin’.

Martin may have flouted social convention but it is equally clear from what Sulpicius has to tell us that his network of contacts among the powerful in the Gaul of his day was extensive. He may have behaved boorishly at the emperor’s dinner table, but Maximus showed ‘the deepest respect’ for him, while on a subsequent visit Maximus’ wife sent the servants away and waited upon him with her own hands. The wife of the brutal Count Avitianus asked Martin to bless the flask of oil which she kept for medicinal use. It was the vir praefectorius Auspicius, an exalted official, who invited Martin over to the Senonais to deal with the local hailstorms. It was from the slave of an even grander man, the vir proconsularis Tetradius, that Martin exorcized a demon. Tetradius became a Christian as a result of this wonder. There is some reason to suppose that he went on to build a church on his estate near Trier. (John Chrysostom would have been pleased.) A letter written by Martin was believed to have cured the daughter of the devout aristocrat Arborius from a fever simply by being placed on her body. Arborius was a very exalted man, a nephew of the celebrated poet Ausonius of Bordeaux, who had been the Emperor Gratian’s tutor.

These connections were of significance in the activity to which Martin devoted so much of his energies. Here was a bishop who gave himself wholeheartedly to the task of bringing Christianity to the rural population of Gaul. His methods were violent and confrontational: disruption of pagan cult, demolition of pagan edifices. Here is Chapter 14 of the Vita Martini.

It was somewhere about this time that in the course of this work he performed another miracle at least as great. He had set on fire a very ancient and much-frequented shrine in a certain village and the flames were being driven by the wind against a neighbouring, in fact adjacent house. When Martin noticed this, he climbed speedily to the roof of the house and placed himself in front of the oncoming flames. Then you might have seen an amazing sight – the flames bending back against the force of the wind till it looked like a battle between warring elements. Such were his powers that the fire destroyed only where it was bidden.

In a village named Levroux [between Tours and Bourges], however, when he wished to demolish in the same way a temple which had been made very rich by its superstitious cult, he met with resistance from a crowd of pagans and was driven off with some injuries to himself. He withdrew, therefore, to a place in the neighbourhood where for three days in sackcloth and ashes, continuously fasting and praying, he besought Our Lord that the temple which human hands had failed to demolish might be destroyed by divine power.

Then suddenly two angels stood before him, looking like heavenly warriors, with spears and shields. They said that the Lord had sent them to rout the rustic host and give Martin protection, so that no one should hinder the destruction of the temple. He was to go back, therefore, and carry out faithfully the work he had undertaken. So he returned to the village and, while crowds of pagans watched in silence, the heathen sanctuary was razed to its foundations and all its altars and images reduced to powder.

The sight convinced the rustics that it was by divine decree that they had been stupefied and overcome with dread, so as to offer no resistance to the bishop; and nearly all of them made profession of faith in the Lord Jesus, proclaiming with shouts before all that Martin’s God should be worshipped and the idols ignored, which could neither save themselves nor anyone else.

There are several points of interest for us in the Levroux story. First, it is notable that Sulpicius admits the – unsurprising – fact that Martin met with resistance. Direct action was risky. In the year of Martin’s death three clerics who tried to disrupt pagan ceremonies in the diocese of Trent in the eastern Alps were killed. Their bishop, Vigilius, to whose letter to John Chrysostom describing the martyrdom we are indebted for knowledge of it, was himself stoned to death by furious pagans a few years later. When the Christian community of Sufetana in the African province of Byzacena demolished a statue of Hercules a pagan mob killed sixty Christians in reprisal. Second, one cannot help wondering a little about the soldierly-looking angels. It is usually fruitless to indulge in speculation about what might have been the ‘real’ basis of miracle stories, but the question can at least be posed, whether Martin was ever enabled to make use of the services of soldiers from local garrisons. It is worth bearing in mind that the fanatically anti-pagan Cynegius, praetorian prefect of the east between 384 and 388, used soldiers as well as bands of wild monks for the destruction of pagan temples in the countryside around Antioch. Martin’s exalted contacts would have been able without difficulty to arrange a bodyguard for him; even to lay on a fatigue party equipped with crowbars and sledgehammers. Third, we are told that these violent scenes at Levroux resulted in conversions; we should note that Sulpicius concedes that not all the people were converted. We have not the remotest idea what the people of Levroux might have thought about it all, but Sulpicius is clear that because their gods had failed them they were prepared to worship Martin’s God. On another occasion, at an unnamed place, Martin had demolished a temple and was preparing to fell a sacred tree. The local people dared him to stand where the tree would fall. Intrepidly, he did so. As the tree tottered, cracked and began to fall, Martin made the sign of the cross. Instantly the tree plunged in another direction. This was the sequel as Sulpicius related it:

Then indeed a shout went up to heaven as the pagans gasped at the miracle, and all with one accord acclaimed the name of Christ; you may be sure that on that day salvation came to that region. Indeed, there was hardly anyone in that vast multitude of pagans who did not ask for the imposition of hands, abandoning his heathenish errors and making profession of faith in the Lord Jesus.

Like it or not, this is what our sources tell us over and over again. Demonstrations of the power of the Christian God meant conversion. Miracles, wonders, exorcisms, temple-torching and shrine-smashing were in themselves acts of evangelization.

Martin was not alone in taking action. His contemporary Bishop Simplicius of Autun is said to have encountered an idol being trundled about on a cart ‘for the preservation of fields and vineyards.’ Simplicius made the sign of the cross; the idol crashed to the ground and the oxen pulling the cart were rooted immobile to the spot; 400 converts were made. Bishop Victricius of Rouen, like Martin an ex-soldier, undertook evangelizing campaigns among the Nervi and the Morini, roughly speaking in the zone of territory between Boulogne and Brussels. We have already met the ill-starred Bishop Vigilius of Trent. Across the Pyrenees in Spain Bishop Priscillian of Avila conducted evangelizing tours of his upland diocese before he was arraigned for heresy.

The interconnections of this clerical society are worth unravelling, if only because we shall repeatedly find in the course of this study that missionary churchmen, though sometimes loners, have tended to be sustained by a network of connections – kinsfolk, friends, patrons, associates in prayer – whose support was invaluable. Priscillian gained a following especially – and it became one of the counts against him – among pious aristocratic ladies. One such observer of his work is likely to have been the heiress Teresa, whose family estates seem to have lain in the region of Complutum (the modern Alcalá de Henares, near Madrid), a mere fifty miles from Avila. Teresa married the immensely rich, devout aristocrat Paulinus of Nola (who was connected to Ausonius). Paulinus knew Martin: he was the beneficiary of one of Martin’s miracles of healing by which the saint cured some sort of infection of the eye. Paulinus it was who introduced Sulpicius Severus to Martin. It is to Paulinus’ polite letter of congratulation that we owe our knowledge about the preaching of Victricius in the north-east of Gaul. Martin knew Victricius: we glimpse them together once at Chartres when Martin cured a girl of twelve who had been dumb from birth. (It would seem that Victricius was among the few Gallic bishops with whom Martin did not mind associating.) Martin also knew Priscillian and his work: he interceded with the Emperor Maximus on behalf of Priscillian when the latter had been found guilty of heresy.

Archaeological discoveries have furnished confirmation of the destruction of sites of pagan worship at this period which, in the words of Paulinus of Nola, was ‘happening throughout Gaul’. At a temple of Mercury at Avallon in Burgundy pagan statues were smashed and piled up in a heap of rubble: the coin series at the site ends in the reign of Valentinian I (364–75), which suggests that the work of destruction occurred shortly afterwards. The shrine of Dea Sequana, which marked the source of the river Seine not far from Dijon, was destroyed at about the same time. Sulpicius locates one of Martin’s temple-smashing exploits in this Burgundian area.

Martin did not only destroy: he also built. ‘He immediately built a church or monastery at every place where he destroyed a pagan shrine,’ tells Sulpicius. Martin’s distant successor as bishop, Gregory of Tours (d. 594), has left us a list of the places where Martin founded churches in the diocese, at Amboise, Candé, Ciran, Langeais, Saunay and Tournon. To these we must add the monastic communities he established at Marmoutier and Clion. These rural churches were staffed by bodies of clergy, as we may see at Candes. Such bodies were probably quite small and few members of them need have been priests; there was only one priest, Marcellus, at Amboise. These foundations were intended to have potential for Christian ministry over a wide area. Sulpicius refers to Martin making customary visits to the churches of his diocese, which would have enabled him to perform his episcopal duties, to check up on his local clergy, to nourish his network of contacts and to disrupt any manifestations of paganism which he might encounter. (It is notable that most of the stories told of Martin by Sulpicius Severus have a journey as their setting.) A structure, even a routine, of episcopal discipline is faintly visible.

Martin’s successors as bishops of Tours carried on the work he had started of building churches at rural settlements in the diocese. Brice, Martin’s first and very long-lived successor (bishop 397–444) built five; Eustochius (444–61), four; Perpetuus (461–91), six; Volusianus (491–8), two. We know of these because they were listed, like Martin’s, by Gregory of Tours towards the end of the sixth century. Gregory did not list these churches out of mere antiquarian interest: he listed them because they were episcopal foundations, the network through which the bishop supervised his diocese. What he does not tell us about, because he had no interest in so doing, was the progress of church-building by laymen on their own lands; estate (or villa) churches built by landowners for their own households and dependants. We hear about such churches only by chance. For example, Gregory introduces a story about the relics of St Nicetius of Lyons with the information that he, Gregory, had been asked to consecrate a church at Pernay. In another of his works we learn that it had been built by a certain Litomer, presumably the lord of the estate. Litomer must have been building his church at Pernay in the 580s. By that date Touraine was fairly densely dotted with churches. It has been plausibly estimated that by Gregory’s day most people in the diocese would have had a church within about six miles of their homes.

It must be emphasized that Touraine is a very special case as regards the extent of our information about it. Thanks to Gregory’s writings we know more about the ecclesiastical organization of the diocese of Tours than we do about any other rural area of comparable size in fourth-, fifth- or sixth-century Christendom. We should never have guessed that there was a church at the little village of Ceyreste, between Marseilles and Toulon, had its control not been disputed between the bishops of Arles and Marseilles: the dispute elicited a papal ruling in 417, the source of our knowledge. We hear about the church at Alise-Sainte-Reine, about ten miles from the ruined shrine of Dea Sequana, only because when St Germanus of Auxerre stayed a night there with its priest in about 430 the straw pallet on which he had slept was found to possess miraculous curative properties: his hagiographer Constantius recorded the fact and thus preserved the notice of the church. It is from the Vita Eugendi that we hear of the existence of a church at Izernore, between Bourg-en-Bresse and Geneva, and from the Vita Genovefae that we hear of a church at Nanterre, then about seven miles from Paris; both of these from the second quarter of the fifth century. At Arlon in Belgium, close to the modern borders with both Luxembourg and France, archaeologists have excavated what might have been a church of the late Roman period: caution is necessary because excavated church buildings from this period are difficult to identify as such. We know that Bishop Rusticus of Narbonne consecrated a new church at Minerve, which has given its name to the wine-growing district of Minervois, in 456 because an inscription recording the fact has survived. At Chantelle, near Vichy, a landowner called Germanicus built a church in the 470s: it is referred to in one of the letters of Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont.

We hear of these churches because of the chance survival of a legal ruling, three pieces of hagiography, the buried foundations of a building, an inscription and a bishop’s letter-collection. It is a ragbag of odds and ends of evidence, some of them of rather doubtful status, characteristic of the coin in which the early medieval historian has to deal. So slender are the threads by which our knowledge hangs, so fragmentary and isolated its separate pieces, that we have to exercise the utmost caution in teasing out what it might have to tell us. To the question, How far may we press our evidence? different historians will give different answers. How representative was Touraine in respect of the building of churches? To what degree, if at all, may we generalize from its circumstances? Were the dioceses of Arles or Auxerre or Paris or Narbonne or Clermont as well provided with rural churches by the year 600 as was the diocese of Tours? These are – given our sources, these have to be – open questions. The reader is free to speculate.

We rarely know anything at all of the precise circumstances which brought any individual rural church into being. Here is an example, deservedly famous, of a case where we do know something: it also shows that not all bishops were as violently confrontational in their methods as Martin was.

In the territory of Javols [on the western edge of the Massif Central] there was a large lake. At a fixed time a crowd of rustics went there and, as if offering libations to the lake, threw into it linen cloths and garments, pelts of wool, models of cheese and wax and bread, each according to his means. They came with their wagons; they brought food and drink, sacrificed animals, and feasted for three days. Much later a cleric from that same city [Javols] became bishop and went to the place. He preached to the crowds that they should cease this behaviour lest they be consumed by the wrath of heaven. But their coarse rusticity rejected his teachings. Then, with the inspiration of the Divinity this bishop of God built a church in honour of the blessed Hilary of Poitiers [Martin’s patron] at a distance from the banks of the lake. He placed relics of Hilary in the church and said to the people: ‘Do not, my sons, sin before God! For there is no religious piety to a lake. Do not stain your hearts with these empty rituals, but rather acknowledge God and direct your devotion to His friends. Respect St Hilary, a bishop of God whose relics are located here. For he can serve as your intercessor for the mercy of the Lord.’ The men were stung in their hearts and converted. They left the lake and brought everything they usually threw into it to the holy church instead. So they were freed from the mistake that had bound them.6

This shrewd manoeuvre by the unnamed bishop of Javols probably occurred in about the year 500. It is a fine example of a technique of rural evangelization which became classic: the transference of ritual from one religious loyalty to another. Gregory of Tours, reporting the story, plainly thought that the bishop had thereby made his lakeside flock more Christian. Perhaps he had.

There is a further layer of interest in the story of the sacred lake of Javols. The episode demonstrates the local standing and authority of the bishop; it may have enhanced them too. We saw some signs of the beginnings of a change in the nature of a bishop’s public role in the career of Gregory of Pontus. Change was accelerated in the wake of Constantine’s conversion. Further impetus was given in the western provinces of the empire in the course of the fifth and sixth centuries. It was during this age that the last tatters of central imperial control were shaken from Britain, Gaul and Spain. As the distinctive marks of functioning Romanitas were whittled away – especially the army and the civil service and their economic underpinning – so bishops tended to become the natural leaders of their local communities.