полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

It is amusing to compare the French histories of the English with the English histories of the Americans, and to notice the similarity of the arguments they use to detract from their opponents' fame. Of course I do not allude to such writers as Lord Howard Douglass or Admiral de la Gravière, but to men like William James and Léon Guérin, or even O. Troude. James is always recounting how American ships ran away from British ones, and Guérin tells as many anecdotes of British ships who fled from French foes. James reproaches the Americans for adopting a "Parthian" mode of warfare, instead of "bringing to in a bold and becoming manner." Precisely the same reproaches are used by the French writers, who assert that the English would not fight "fairly," but acquired an advantage by manoeuvring. James lays great stress on the American long guns; so does Lieutenant Rouvier on the British carronades. James always tells how the Americans avoided the British ships, when the crews of the latter demanded to be led aboard; Troude says the British always kept at long shot, while the French sailors "demandérent, à grands cris, l'abordage." James says the Americans "hesitated to grapple" with their foes "unless they possessed a twofold superiority"; Guérin that the English "never dared attack" except when they possessed "une supériorité énorme." The British sneer at the "mighty dollar"; the French at the "eternal guinea." The former consider Decatur's name as "sunk" to the level of Porter's or Bainbridge's; the latter assert that the "presumptuous Nelson" was inferior to any of the French admirals of the time preceding the Republic. Says James: "The Americans only fight well when they have the superiority of force on their side"; and Lieutenant Rouvier: "Never have the English vanquished us with an undoubted inferiority of force."

On June 12, 1813, the small cutter Surveyor, of 6 12-pound carronades, was lying in York River, in the Chesapeake, under the command of Mr. William S. Travis; her crew consisted of but 15 men. [Footnote: Letter of W. S. Travis, June 16, 1813.] At nightfall she was attacked by the boats of the Narcissus frigate, containing about 50 men, under the command of Lieutenant John Creerie. [Footnote: James, vi. 334.] None of the carronades could be used; but Mr. Travis made every preparation that he could for defence. The Americans waited till the British were within pistol shot before they opened their fire; the latter dashed gallantly on, however, and at once carried the cutter. But though brief, the struggle was bloody; 5 of the Americans were wounded, and of the British 3 were killed and 7 wounded. Lieutenant Creerie considered his opponents to have shown so much bravery that he returned Mr. Travis his sword, with a letter as complimentary to him as it was creditable to the writer. [Footnote: The letter, dated June 13th, is as follows: "Your gallant and desperate attempt to defend your vessel against more than double your number, on the night of the 12th instant, excited such admiration on the part of your opponents as I have seldom witnessed, and induced me to return you the sword you had so nobly used, in testimony of mine. Our poor fellows have suffered severely, occasioned chiefly, if not solely, by the precautions you had taken to prevent surprise. In short, I am at a loss which to admire most, the previous arrangement aboard the Surveyor, or the determined manner in which her deck was disputed inch by inch. I am, sir," etc.]

As has been already mentioned, the Americans possessed a large force of gun-boats at the beginning of the war. Some of these were fairly sea-worthy vessels, of 90 tons burden, sloop—or schooner-rigged, and armed with one or two long, heavy guns, and sometime with several light carronades to repel boarders. [Footnote: According to a letter from Captain Hugh G. Campbell (in the Naval Archives, "Captains' Letters," 1812, vol. ii. Nos. 21 and 192), the crews were distributed as follows: ten men and a boy to a long 32. seven men and a boy to a long 9. and five men and a boy to a carronade, exclusive of petty officers. Captain Campbell complains of the scarcity of men, and rather naively remarks that he is glad the marines have been withdrawn from the gun boats, as this may make the commanders of the latter keep a brighter lookout than formerly.] Gun-boats of this kind, together with the few small cutters owned by the government, were serviceable enough. They were employed all along the shores of Georgia and the Carolinas, and in Long Island Sound, in protecting the coasting trade by convoying parties of small vessels from one port to another, and preventing them from being molested by the boats of any of the British frigates. They also acted as checks upon the latter in their descents upon the towns and plantations, occasionally capturing their boats and tenders, and forcing them to be very cautious in their operations. They were very useful in keeping privateers off the coast, and capturing them when they came too far in. The exploits of those on the southern coast will be mentioned as they occurred. Those in Long Island Sound never came into collision with the foe, except for a couple of slight skirmishes at very long range; but in convoying little fleets of coasters, and keeping at bay the man-of-war boats sent to molest them, they were invaluable; and they also kept the Sound clear of hostile privateers.

Many of the gun-boats were much smaller than those just mentioned, trusting mainly to their sweeps for motive power, and each relying for offence on one long pivot gun, a 12- or 18-pounder. In the Chesapeake there was a quite a large number of these small gallies, with a few of the larger kind, and here it was thought that by acting together in flotillas the gun-boats might in fine weather do considerable damage to the enemy's fleet by destroying detached vessels, instead of confining themselves to the more humble tasks in which their brethren elsewhere were fairly successful. At this period Denmark, having lost all her larger ships of war, was confining herself purely to gun-brigs. These were stout little crafts, with heavy guns, which, acting together, and being handled with spirit and skill, had on several occasions in calm weather captured small British sloops, and had twice so injured frigates as to make their return to Great Britain necessary; while they themselves had frequently been the object of successful cutting-out expeditions. Congress hoped that our gun-boats would do as well as the Danish; but for a variety of reasons they failed utterly in every serious attack that they made on a man-of-war, and were worse than useless for all but the various subordinate employments above mentioned. The main reason for this failure was in the gun-boats themselves. They were utterly useless except in perfectly calm weather, for in any wind the heavy guns caused them to careen over so as to make it difficult to keep them right side up, and impossible to fire. Even in smooth water they could not be fought at anchor, requiring to be kept in position by means of sweeps; and they were very unstable, the recoil of the guns causing them to roll so as to make it difficult to aim with any accuracy after the first discharge, while a single shot hitting one put it hors de combat. This last event rarely happened, however, for they were not often handled with any approach to temerity, and, on the contrary, usually made their attacks at a range that rendered it as impossible to inflict as to receive harm. It does not seem as if they were very well managed; but they were such ill-conditioned craft that the best officers might be pardoned for feeling uncomfortable in them. Their operations throughout the war offer a painfully ludicrous commentary on Jefferson's remarkable project of having our navy composed exclusively of such craft.

The first aggressive attempt made with the gun-boats was characteristically futile. On June 20th 15 of them, under Captain Tarbell, attacked the Junon, 38, Captain Sanders, then lying becalmed in Hampton Roads, with the Barossa, 36, and Laurestinus, 24, near her. The gun-boats, while still at very long range, anchored, and promptly drifted round so that they couldn't shoot. Then they got under way, and began gradually to draw nearer to the Junon. Her defence was very feeble; after some hasty and ill-directed vollies she endeavored to beat out of the way. But meanwhile, a slight breeze having sprung up, the Barossa, Captain Sherriff, approached near enough to take a hand in the affair, and at once made it evident that she was a more dangerous foe than the Junon, though a lighter ship. As soon as they felt the effects of the breeze the gun-boats became almost useless and, the Barossa's fire being animated and well aimed, they withdrew. They had suffered nothing from the Junon, but during the short period she was engaged, the Barossa had crippled one boat and slightly damaged another; one man was killed and two wounded. The Barossa escaped unscathed and the Junon was but slightly injured. Of the combatants, the Barossa was the only one that came off with credit, the Junon behaving, if any thing, rather worse than the gun-boats. There was no longer any doubt as to the amount of reliance to be placed on the latter. [Footnote: Though the flotilla men did nothing in the boats, they acted with the most stubborn bravery at the battle of Bladensburg. The British Lieutenant Graig, himself a spectator, thus writes of their deeds on that occasion ("Campaign at Washington," p. 119). "Of the sailors, however, it would be injustice not to speak in the terms which their conduct merits. They were employed as gunners, and not only did they serve their guns with a quickness and precision which astonished their assailants, but they stood till some of them were actually bayoneted with fuses in their hands; nor was it till their leader was wounded and taken, and they saw themselves deserted on all sides by the soldiers, that they quitted the field." Certainly such men could not be accused of lack of courage. Something else is needed to account for the failure of the gun-boat system.]

On June 20, 1813, a British force of three 74's, one 64, four frigates, two sloops, and three transports was anchored off Craney Island. On the north-west side of this island was a battery of 18-pounders, to take charge of which Captain Cassin, commanding the naval forces at Norfolk, sent ashore one hundred sailors of the Constellation, under the command of Lieutenants Neale, Shubrick, and Saunders, and fifty marines under Lieutenant Breckenbridge.[Footnote: Letter of Captain John Cassin, June 23, 1813.] On the morning of the 22d they were attacked by a division of 15 boats, containing 700 men, [Footnote: James, vi, 337.] seamen, marines, chasseurs, and soldiers of the 102d regiment, the whole under the command of Captain Pechell, of the San Domingo, 74. Captain Hanchett led the attack in the Diadem's launch. The battery's guns were not fired till the British were close in, when they opened with destructive effect. While still some seventy yards from the guns the Diadem's launch grounded, and the attack was checked. Three of the boats were now sunk by shot, but the water was so shallow that they remained above water; and while the fighting was still at its height, some of the Constellation's crew, headed by Midshipman Tatnall, waded out and took possession of them. [Footnote: "Life of Commodore Josiah Tatnall," by Charles C. Jones, Jr. (Savannah, 1878), p. 17.] A few of their crew threw away their arms and came ashore with their captors; others escaped to the remaining boats, and immediately afterward the flotilla made off in disorder having lost 91 men. The three captured barges were large, strong boats, one called the Centipede being fifty feet long, and more formidable than many of the American gun-vessels. The Constellation's men deserve great credit for their defence, but the British certainly did not attack with their usual obstinacy. When the foremost boats were sunk, the water was so shallow and the bottom so good that the Americans on shore, as just stated, at once waded out to them; and if in the heat of the fight Tatnall and his seamen could get out to the boats, the 700 British ought to have been able to get in to the battery, whose 150 defenders would then have stood no chance. [Footnote: James comments on this repulse as "a defeat as discreditable to those that caused it as honorable to those that suffered in it." "Unlike most other nations, the Americans in particular, the British, when engaged in expeditions of this nature, always rest their hopes of success upon valor rather than on numbers." These comments read particularly well when it is remembered that the assailants outnumbered the assailed in the proportion of 5 to 1. It is monotonous work to have to supplement a history by a running commentary on James' mistakes and inventions; but it is worth while to prove once for all the utter unreliability of the author who is accepted in Great Britain as the great authority about the war. Still, James is no worse than his compeers. In the American Coggeshall's "History of Privateers," the misstatements are as gross and the sneers in as poor taste—the British, instead of the Americans, being the objects.]

On July 14, 1813, the two small vessels Scorpion and Asp, the latter commanded by Mr. Sigourney, got under way from out of the Yeocomico Creek, [Footnote: Letter of Midshipman McClintock, July 15, 1813.] and at 10 A.M. discovered in chase the British brig-sloops Contest, Captain James Rattray, and Mohawk, Captain Henry D. Byng. [Footnote: James, vi, 343.] The Scorpion beat up the Chesapeake, but the dull-sailing Asp had to reenter the creek; the two brigs anchored off the bar and hoisted out their boats, under the command of Lieutenant Rodger C. Curry; whereupon the Asp cut her cable and ran up the creek some distance. Here she was attacked by three boats, which Mr. Sigourney and his crew of twenty men, with two light guns, beat off; but they were joined by two others, and the five carried the Asp, giving no quarter. Mr. Sigourney and 10 of his men were killed or wounded, while the British also suffered heavily, having 4 killed and 7 (including Lieutenant Curry) wounded. The surviving Americans reached the shore, rallied under Midshipman H. McClintock (second in command), and when the British retired after setting the Asp on fire, at once boarded her, put out the flames, and got her in fighting order; but they were not again molested.

On July 29th, while the Junon, 38, Captain Sanders, and Martin, 18, Captain Senhouse, were in Delaware Bay, the latter grounded on the outside of Crow's Shoal; the frigate anchored within supporting distance, and while in this position the two ships were attacked by the American flotilla in those waters, consisting of eight gun-boats, carrying each 25 men and one long 32, and two heavier block-sloops, [Footnote: Letter of Lieutenant Angus, July 30, 1813.] commanded by Lieutenant Samuel Angus. The flotilla kept at such a distance that an hour's cannonading did no damage whatever to anybody; and during that time gun-boat No. 121, Sailing-master Shead, drifted a mile and a half away from her consorts. Seeing this the British made a dash at her, in 7 boats, containing 140 men, led by Lieutenant Philip Westphal. Mr. Shead anchored and made an obstinate defence, but at the first discharge the gun's pintle gave way, and the next time it was fired the gun-carriage was almost torn to pieces. He kept up a spirited fire of small arms, in reply to the boat-carronades and musketry of the assailants; but the latter advanced steadily and carried the gun-boat by boarding, 7 of her people being wounded, while 7 of the British were killed and 13 wounded. [Footnote: Letter of Mr. Shead. Aug. 5, 1813.] The defence of No. 121 was very creditable, but otherwise the honor of the day was certainly with the British; whether because the gun-boats were themselves so worthless or because they were not handled boldly enough, they did no damage, even to the grounded sloop, that would seem to have been at their mercy. [Footnote: The explanation possibly lies in the fact that the gun-boats had worthless powder. In the Naval Archives there is a letter from Mr. Angus ("Masters' Commandant Letters," 1813, No. 3: see also No. 91), in which he says that the frigate's shot passed over them, while theirs could not even reach the sloop. He also encloses a copy of a paper, signed by the other gun-boat officers, which runs: "We, the officers of the vessels comprising the Delaware flotilla, protest against the powder as being unfit for service."]

On June 18th the American brig-sloop Argus, commanded by Lieutenant William Henry Allen, late first of the United States, sailed from New York for France, with Mr. Crawford, minister for that country, aboard, and reached L'Orient on July 11th, having made one prize on the way. On July 14th she again sailed, and cruised in the chops of the Channel, capturing and burning ship after ship, and creating the greatest consternation among the London merchants; she then cruised along Cornwall and got into St. George's Channel, where the work of destruction went on. The labor was very severe and harassing, the men being able to get very little rest. [Footnote: Court of Inquiry into loss of Argus, 1815.] On the night of August 13th, a brig laden with wine from Oporto was captured and burnt, and unluckily many of the crew succeeded in getting at some of the cargo. At 5 A.M. on the 14th a large brig-of-war was discovered standing down under a cloud of canvas. [Footnote: Letter of Lieutenant Watson, March 2, 1815.] This was the British brig-sloop Pelican, Captain John Fordyce Maples, which, from information received at Cork three days previous, had been cruising especially after the Argus, and had at last found her; St. David's Head bore east five leagues (lat. 52° 15' N. and 5° 50' W.)

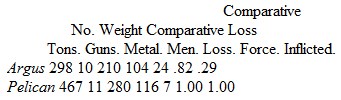

The small, fine-lined American cruiser, with her lofty masts and long spars, could easily have escaped from her heavier antagonist: but Captain Allen had no such intention, and, finding he could not get the weather-gage, he shortened sail and ran easily along on the starboard tack, while the Pelican came down on him with the wind (which was from the south) nearly aft. At 6 A.M. the Argus wore and fired her port guns within grape distance, the Pelican responding with her starboard battery, and the action began with great spirit on both sides. [Footnote: Letter of Captain Maples to Admiral Thornborough, Aug. 14, 1813.] At 6.04 a round shot carried off Captain Allen's leg, inflicting a mortal wound, but he stayed on deck till he fainted from loss of blood. Soon the British fire carried away the main-braces, main-spring-stay, gaff, and try-sail mast of the Argus; the first lieutenant, Mr. Watson, was wounded in the head by a grape-shot and carried below; the second lieutenant, Mr. U. H. Allen (no relation of the captain), continued to fight the ship with great skill. The Pelican's fire continued very heavy, the Argus losing her spritsail-yard and most of the standing rigging on the port side of the foremast. At 6.14 Captain Maples bore up to pass astern of his antagonist, but Lieutenant Allen luffed into the wind and threw the main-top-sail aback, getting into a beautiful raking position [Footnote: Letter of Lieutenant Watson.]; had the men at the guns done their duty as well as those on the quarter-deck did theirs, the issue of the fight would have been very different; but, as it was, in spite of her favorable position, the raking broadside of the Argus did little damage. Two or three minutes afterward the Argus lost the use of her after-sails through having her preventer-main-braces and top-sail tie shot away, and fell off before the wind, when the Pelican at 6.18 passed her stern, raking her heavily, and then ranged up on her starboard quarter. In a few minutes the wheel-ropes and running-rigging of every description were shot away, and the Argus became utterly unmanageable. The Pelican continued raking her with perfect impunity, and at 6.35 passed her broadside and took a position on her starboard bow, when at 6.45 the brigs fell together, and the British "were in the act of boarding when the Argus struck her colors," [Footnote: Letter of Captain Maples.] at 6.45 A.M. The Pelican carried, besides her regular armament, two long 6's as stern-chasers, and her broadside weight of metal was thus: [Footnote: James, vi, 320.]

1 X 6 1 X 6 1 X 12 8 X 32

or 280 lbs. against the Argus':

1 X 12 9 X 24

or, subtracting as usual 7 per cent. for light weight of metal, 210 lbs. The Pelican's crew consisted of but 116 men, according to the British account, though the American reports make it much larger. The Argus had started from New York with 137 men, but having manned and sent in several prizes, her crew amounted, as near as can be ascertained, to 104. Mr. Low in his "Naval History," published just after the event, makes it but 99. James makes it 121; as he placed the crew of the Enterprise at 125, when it was really 102; that of the Hornet at 162, instead of 135; of the Peacock at 185, instead of 166; of the Nautilus at 106 instead of 95, etc., etc., it is safe to presume that he has overestimated it by at least 20, which brings the number pretty near to the American accounts. The Pelican lost but two men killed and five wounded. Captain Maples had a narrow escape, a spent grape-shot striking him in the chest with some force, and then falling on the deck. One shot had passed through the boatswain's and one through the carpenter's cabin; her sides were filled with grape-shot, and her rigging and sails much injured; her foremast, main-top-mast, and royal masts were slightly wounded, and two of her carronades dismounted.

The injuries of the Argus have already been detailed; her hull and lower masts were also tolerably well cut up. Of her crew, Captain Allen, two midshipmen, the carpenter, and six seamen were killed or mortally wounded; her first lieutenant and 13 seamen severely and slightly wounded: total, 10 killed and 14 wounded.

In reckoning the comparative force, I include the Englishman's six-pound stern-chaser, which could not be fired in broadside with the rest of the guns, because I include the Argus' 12-pound bow-chaser, which also could not be fired in broadside, as it was crowded into the bridle-port. James, of course, carefully includes the latter, though leaving out the former.

[Illustration: Argus vs. Pelican: an engraving published in London in 1817. (Courtesy Beverley R. Robinson Collection, U.S. Naval Academy Museum)]

COMPARISON.

[Illustration of ARGUS and PELICAN action from 6.00 A.M. to 6.45]

Of all the single-ship actions fought in the war this is the least creditable to the Americans. The odds in force, it is true, were against the Argus, about in the proportion of 10 to 8, but this is neither enough to account for the loss inflicted being as 10 to 3, nor for her surrendering when she had been so little ill used. It was not even as if her antagonist had been an unusually fine vessel of her class. The Pelican did not do as well as either the Frolic previously, or the Reindeer afterward, though perhaps rather better than the Avon, Penguin, or Peacock. With a comparatively unmanageable antagonist, in smooth water, she ought to have sunk her in three quarters of an hour. But the Pelican's not having done particularly well merely makes the conduct of the Americans look worse; it is just the reverse of the Chesapeake's case, where, paying the highest credit to the British, we still thought the fight no discredit to us. Here we can indulge no such reflection. The officers did well, but the crew did not. Cooper says: "The enemy was so much heavier that it may be doubted whether the Argus would have captured her antagonist under any ordinary circumstances." This I doubt; such a crew as the Wasp's or Hornet's probably would have been successful. The trouble with the guns of the Argus was not so much that they were too small, as that they did not hit; and this seems all the more incomprehensible when it is remembered that Captain Allen is the very man to whom Commodore Decatur, in his official letter, attributed the skilful gun-practice of the crew of the frigate United States. Cooper says that the powder was bad; and it has also been said that the men of the Argus were over-fatigued and were drunk, in which case they ought not to have been brought into action. Besides unskilfulness, there is another very serious count against the crew. Had the Pelican been some distance from the Argus, and in a position where she could pour in her fire with perfect impunity to herself, when the surrender took place, it would have been more justifiable. But, on the contrary, the vessels were touching, and the British boarded just as the colors were hauled down; it was certainly very disgraceful that the Americans did not rally to repel them, for they had still four fifths of their number absolutely untouched. They certainly ought to have succeeded, for boarding is a difficult and dangerous experiment; and if they had repulsed their antagonists they might in turn have carried the Pelican. So that, in summing up the merits of this action, it is fair to say that both sides showed skilful seamanship and unskilful gunnery; that the British fought bravely and that the Americans did not.