полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

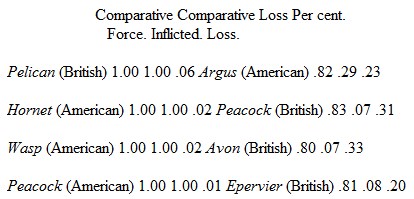

It is somewhat interesting to compare this fight, where a weaker American sloop was taken by a stronger British one, with two or three others, where both the comparative force and the result were reversed. Comparing it, therefore, with the actions between the Hornet and Peacock (British), the Wasp and Avon, and the Peacock (American) and Epervier, we get four actions, in one of which, the first-named, the British were victorious, and in the other three the Americans.

It is thus seen that in these sloop actions the superiority of force on the side of the victor was each time about the same. The Argus made a much more effectual resistance than did either the Peacock, Avon, or Epervier, while the Pelican did her work in poorer form than either of the victorious American sloops; and, on the other hand, the resistance of the Argus did not by any means show as much bravery as was shown in the defence of the Peacock or Avon, although rather more than in the case of the Epervier.

This is the only action of the war where it is almost impossible to find out the cause of the inferiority of the beaten crew. In almost all other cases we find that one crew had been carefully drilled, and so proved superior to a less-trained antagonist; but it is incredible that the man, to whose exertions when first lieutenant of the States Commodore Decatur ascribes the skilfulness of that ship's men, should have neglected to train his own crew; and this had the reputation of being composed of a fine set of men. Bad powder would not account for the surrender of the Argus when so little damaged. It really seems as if the men must have been drunk or over-fatigued, as has been so often asserted. Of course drunkenness would account for the defeat, although not in the least altering its humiliating character.

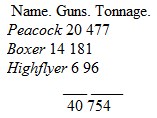

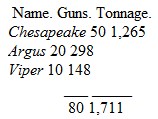

"Et tu quoque" is not much of an argument; still it may be as well to call to mind here two engagements in which British sloops suffered much more discreditable defeats than the Argus did. The figures are taken from James; as given by the French historians they make even a worse showing for the British.

A short time before our war the British brig Carnation, 18, had been captured, by boarding, by the French brig Palinure, 16, and the British brig Alacrity, 18, had been captured, also by boarding, by the corvette Abeille, 20.

The following was the comparative force, etc., of the combatants:

Weight Metal. No. Crew. Loss. Carnation 262 117 40 Palmure 174 100 20

Alacrity 262 100 18 Abeille 260 130 19

In spite of the pride the British take in their hand-to-hand prowess both of these ships were captured by boarding. The Carnation was captured by a much smaller force, instead of by a much larger one, as in the case of the Argus; and if the Argus gave up before she had suffered greatly, the Alacrity surrendered when she had suffered still less. French historians asserted that the capture of the two brigs proved that "French valor could conquer British courage"; and a similar opinion was very complacently expressed by British historians after the defeat of the Argus. All that the three combats really "proved" was, that in eight encounters between British and American sloops the Americans were defeated once, and in a far greater number of encounters between French and British sloops the British were defeated twice. No one pretends that either navy was invincible; the question is, which side averaged best?

At the opening of the war we possessed several small brigs; these had originally been fast, handy little schooners, each armed with 12 long sixes, and with a crew of 60 men. As such they were effective enough; but when afterward changed into brigs, each armed with a couple of extra guns, and given 40 additional men, they became too slow to run, without becoming strong enough to fight. They carried far too many guns and men for their size, and not enough to give them a chance with any respectable opponent; and they were almost all ignominiously captured. The single exception was the brig Enterprise. She managed to escape capture, owing chiefly to good luck, and once fought a victorious engagement, thanks to the fact that the British possessed a class of vessels even worse than our own. She was kept near the land and finally took up her station off the eastern coast, where she did good service in chasing away or capturing the various Nova Scotian or New Brunswick privateers, which were smaller and less formidable vessels than the privateers of the United States, and not calculated for fighting.

By crowding guns into her bridle-ports, and over-manning herself, the Enterprise, now under the command of Lieutenant William Burrows, mounted 14 eighteen-pound carronades and 2 long 9's, with 102 men. On September 5th, while standing along shore near Penguin Point, a few miles to the eastward of Portland, Me., she discovered, at anchor inside, a man-of-war brig [Footnote: Letter from Lieutenant Edward R. McCall to Commodore Hull, September 5, 1813.] which proved to be H.M.S. Boxer, Captain Samuel Blyth, of 12 carronades, eighteen-pounders and two long sixes, with but 66 men aboard, 12 of her crew being absent.[Footnote: James, "Naval Occurrences," 264. The American accounts give the Boxer 104 men, on very insufficient grounds. Similarly, James gives the Enterprise 123 men. Each side will be considered authority for its own force and loss.] The Boxer at once hoisted three British ensigns and bore up for the Enterprise, then standing in on the starboard tack; but when the two brigs were still 4 miles apart it fell calm. At midday a breeze sprang up from the southwest, giving the American the weather-gage, but the latter manoeuvred for some time to windward to try the comparative rates of sailing of the vessels. At 3 P.M. Lieutenant Burrows hoisted three ensigns, shortened sail, and edged away toward the enemy, who came gallantly on. Captain Blyth had nailed his colors to the mast, telling his men they should never be struck while he had life in his body. [Footnote: "Naval Chronicle," vol. xxxii, p. 462.] Both crews cheered loudly as they neared each other, and at 3.15, the two brigs being on the starboard tack not a half pistol-shot apart, they opened fire, the American using the port, and the English the starboard, battery. Both broadsides were very destructive, each of the commanders falling at the very beginning of the action. Captain Blyth was struck by an eighteen-pound shot while he was standing on the quarter-deck; it passed completely through his body, shattering his left arm and killing him on the spot. The command, thereupon, devolved on Lieutenant David McCreery. At almost the same time his equally gallant antagonist fell. Lieutenant Burrows, while encouraging his men, laid hold of a gun-tackle fall to help the crew of a carronade run out the gun; in doing so he raised one leg against the bulwark, when a canister shot struck his thigh, glancing into his body and inflicting a fearful wound. [Footnote: Cooper, "Naval History," vol. ii, p. 259.] In spite of the pain he refused to be carried below, and lay on the deck, crying out that the colors must never be struck. Lieutenant Edward McCall now took command. At 3.30 the Enterprise ranged ahead, rounded to on the starboard tack, and raked the Boxer with the starboard guns. At 3.35 the Boxer lost her main-top-mast and top-sail yard, but her crew still kept up the fight bravely, with the exception of four men who deserted their quarters and were afterward court-martialed for cowardice. [Footnote: Minutes of court-martial held aboard H.M.S. Surprise, January 8, 1814.] The Enterprise now set her fore-sail and took position on the enemy's starboard bow, delivering raking fires; and at 3.45 the latter surrendered, when entirely unmanageable and defenceless. Lieutenant Burrows would not go below until he had received the sword of his adversary, when he exclaimed, "I am satisfied, I die contented."

[Illustration of action between ENTERPRISE and BOXER from 3.15 to 3.45]

Both brigs had suffered severely, especially the Boxer, which had been hulled repeatedly, had three eighteen-pound shot through her foremast, her top-gallant forecastle almost cut away, and several of her guns dismounted. Three men were killed and seventeen wounded, four mortally. The Enterprise had been hulled by one round and many grape; one 18-pound ball had gone through her foremast, and another through her main-mast, and she was much cut up aloft. Two of her men were killed and ten wounded, two of them (her commander and Midshipman Kervin Waters) mortally. The British court-martial attributed the defeat of the Boxer "to a superiority in the enemy's force, principally in the number of men, as well as to a greater degree of skill in the direction of her fire, and to the destructive effects of the first broadside." But the main element was the superiority in force, the difference in loss being very nearly proportional to it; both sides fought with equal bravery and equal skill. This fact was appreciated by the victors, for at a naval dinner given in New York shortly afterward, one of the toasts offered was: "The crew of the Boxer; enemies by law, but by gallantry brothers." The two commanders were both buried at Portland, with all the honors of war. The conduct of Lieutenant Burrows needs no comment. He was an officer greatly beloved and respected in the service. Captain Blyth, on the other side, had not only shown himself on many occasions to be a man of distinguished personal courage, but was equally noted for his gentleness and humanity. He had been one of Captain Lawrence's pall-bearers, and but a month previous to his death had received a public note of thanks from an American colonel, for an act of great kindness and courtesy. [Footnote: "Naval Chronicle," xxxii, 466.]

The Enterprise, under Lieut.-Com. Renshaw, now cruised off the southern coast, where she made several captures. One of them was a heavy British privateer, the Mars, of 14 long nines and 75 men, which struck after receiving a broadside that killed and wounded 4 of her crew. The Enterprise was chased by frigates on several occasions; being once forced to throw overboard all her guns but two, and escaping only by a shift in the wind. Afterward, as she was unfit to cruise, she was made a guard-ship at Charlestown; for the same reason the Boxer was not purchased into the service.

On October 4th some volunteers from the Newport flotilla captured, by boarding, the British privateer Dart, [Footnote: Letter of Mr. Joseph Nicholson, Oct. 5, 1813.] after a short struggle in which two of the assailants were wounded and several of the privateersmen, including the first officer, were killed.

On December 4th, Commodore Rodgers, still in command of the President, sailed again from Providence, Rhode Island. On the 25th, in lat. 19° N. and long. 35° W., the President, during the night, fell in with two frigates, and came so close that the head-most fired at her, when she made off. These were thought to be British, but were in reality the two French 40-gun frigates Nymphe and Meduse, one month out of Brest. After this little encounter Rodgers headed toward the Barbadoes, and cruised to windward of them.

On the whole the ocean warfare of 1813 was decidedly in favor of the British, except during the first few months. The Hornet's fight with the Peacock was an action similar to those that took place in 1812, and the cruise of Porter was unique in our annals, both for the audacity with which it was planned, and the success with which it was executed. Even later in the year the Argus and the President made bold cruises in sight of the British coasts, the former working great havoc among the merchant-men. But by that time the tide had turned strongly in favor of our enemies. From the beginning of summer the blockade was kept up so strictly that it was with difficulty any of our vessels broke through it; they were either chased back or captured. In the three actions that occurred, the British showed themselves markedly superior in two, and in the third the combatants fought equally well, the result being fairly decided by the fuller crew and slightly heavier metal of the Enterprise. The gun-boats, to which many had looked for harbor defence, proved nearly useless, and were beaten off with ease whenever they made an attack.

The lessons taught by all this were the usual ones. Lawrence's victory in the Hornet showed the superiority of a properly trained crew to one that had not been properly trained; and his defeat in the Chesapeake pointed exactly the same way, demonstrating in addition the folly of taking a raw levy out of port, and, before they have had the slightest chance of getting seasoned, pitting them against skilled veterans. The victory of the Enterprise showed the wisdom of having the odds in men and metal in our favor, when our antagonist was otherwise our equal; it proved, what hardly needed proving, that, whenever possible, a ship should be so constructed as to be superior in force to the foes it would be likely to meet. As far as the capture of the Argus showed any thing, it was the advantage of heavy metal and the absolute need that a crew should fight with pluck. The failure of the gun-boats ought to have taught the lesson (though it did not) that too great economy in providing the means of defence may prove very expensive in the end, and that good officers and men are powerless when embarked in worthless vessels. A similar point was emphasized by the strictness of the blockade, and the great inconvenience it caused; namely, that we ought to have had ships powerful enough to break it.

We had certainly lost ground during this year; fortunately we regained it during the next two.

BRITISH VESSELS SUNK OR TAKEN.

AMERICAN VESSELS SUNK OR TAKEN.

VESSELS BUILT OR PURCHASED.

Name. Rig. Guns. Tonnage. Where Built. Cost. Rattlesnake Brig 14 278 Medford, Pa. $18,000 Alligator Schooner 4 80 Asp Sloop 3 56 2,600

PRIZES MADE.

Name of Ship. No. of Prizes. President 13 Congress 4 Chesapeake 6 Essex 14 Hornet 3 Argus 21 Small craft 18 ___ 79

Chapter VI

1813ON THE LAKESONTARIO—Comparison of the rival squadrons–Chauncy takes York and Fort George—Yeo is repulsed at Sackett's Harbor, but keeps command of the lake—Chauncy sails—Yeo's partial victory off Niagara–Indecisive action off the Genesee—Chauncy's partial victory off Burlington, which gives him the command of the lake—ERIE—Perry's success in creating a fleet—His victory—CHAMPLAIN—Loss of the Growler and Eagle—Summary.

ONTARIO.

Winter had almost completely stopped preparations on the American side. Bad weather put an end to all communication with Albany or New York, and so prevented the transit of stores, implements, etc. It was worse still with the men, for the cold and exposure so thinned them out that the new arrivals could at first barely keep the ranks filled. It was, moreover, exceedingly difficult to get seamen to come from the coast to serve on the lakes, where work was hard, sickness prevailed, and there was no chance of prize-money. The British government had the great advantage of being able to move its sailors where it pleased, while in the American service, at that period, the men enlisted for particular ships, and the only way to get them for the lakes at all was by inducing portions of crews to volunteer to follow their officers thither. [Footnote: Cooper, ii, 357. One of James' most comical misstatements is that on the lakes the American sailors were all "picked men." On p. 367, for example, in speaking of the battle of Lake Erie he says: "Commodore Perry had picked crews to all his vessels." As a matter of fact Perry had once sent in his resignation solely on account of the very poor quality of his crews, and had with difficulty been induced to withdraw it. Perry's crews were of hardly average excellence, but then the average American sailor was a very good specimen.] However, the work went on in spite of interruptions. Fresh gangs of shipwrights arrived, and, largely owing to the energy and capacity of the head builder, Mr. Henry Eckford (who did as much as any naval officer in giving us an effective force on Ontario), the Madison was equipped, a small despatch sloop, The Lady of the Lake prepared, and a large new ship, the General Pike, 28, begun, to mount 13 guns in each broadside and 2 on pivots.

Meanwhile Sir George Prevost, the British commander in Canada, had ordered two 24-gun ships to be built, and they were begun; but he committed the mistake of having one laid down in Kingston and the other in York, at the opposite end of the lake. Earle, the Canadian commodore, having proved himself so incompetent, was removed; and in the beginning of May Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo arrived, to act as commander-in-chief of the naval forces, together with four captains, eight lieutenants, twenty-four midshipmen, and about 450 picked seamen, sent out by the home government especially for service on the Canada lakes. [Footnote: James, vi, 353.]

The comparative force of the two fleets or squadrons it is hard to estimate. I have already spoken of the difficulty in finding out what guns were mounted on any given ship at a particular time, and it is even more perplexing with the crews. A schooner would make one cruise with but thirty hands; on the next it would appear with fifty, a number of militia having volunteered as marines. Finding the militia rather a nuisance, they would be sent ashore, and on her third cruise the schooner would substitute half a dozen frontier seamen in their place. It was the same with the larger vessels. The Madison might at one time have her full complement of 200 men; a month's sickness would ensue, and she would sail with but 150 effectives. The Pike's crew of 300 men at one time would shortly afterward be less by a third in consequence of a draft of sailors being sent to the upper lakes. So it is almost impossible to be perfectly accurate; but, making a comparison of the various authorities from Lieutenant Emmons to James, the following tables of the forces may be given as very nearly correct. In broadside force I count every pivot gun, and half of those that were not on pivots.

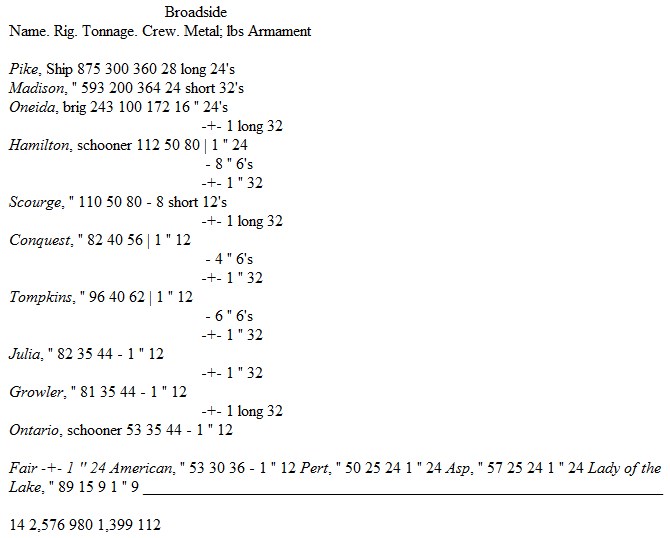

CHAUNCY'S SQUADRON.

This is not materially different from James' account (p. 356), which gives Chauncy 114 guns, 1,193 men, and 2,121 tons. The Lady of the Lake, however, was never intended for anything but a despatch boat, and the Scourge and Hamilton were both lost before Chauncy actually came into collision with Yeo. Deducting these, in order to compare the two foes, Chauncy had left 11 vessels of 2,265 tons, with 865 men and 92 guns throwing a broadside of 1,230 pounds.

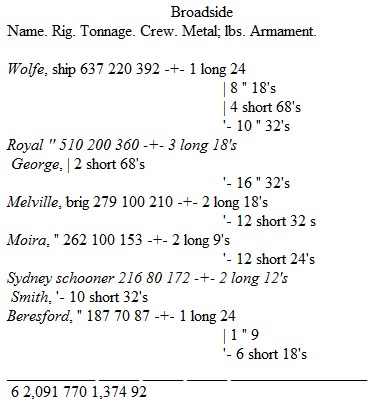

YEO'S SQUADRON.

This differs but slightly from James, who gives Yeo 92 guns throwing a broadside of 1,374 pounds, but only 717 men. As the evidence in the court-martial held on Captain Barclay, and the official accounts (on both sides) of Macdonough's victory, convict him of very much underrating the force in men of the British on Erie and Champlain, it can be safely assumed that he has underestimated the force in men on Lake Ontario. By comparing the tonnage he gives to Barclay's and Downie's squadrons with what it really was, we can correct his account of Yeo's tonnage.

The above figures would apparently make the two squadrons about equal, Chauncy having 95 men more, and throwing at a broadside 144 pounds shot less than his antagonist. But the figures do not by any means show all the truth. The Americans greatly excelled in the number and calibre of their long guns. Compared thus, they threw at one discharge 694 pounds of long-gun metal and 536 pounds of carronade metal; while the British only threw from their long guns 180 pounds, and from their carronades 1,194. This unequal distribution of metal was very much in favor of the Americans. Nor was this all. The Pike, with her 15 long 24's in battery was an overmatch for any one of the enemy's vessels, and bore the same relation to them that the Confiance, at a later date, did to Macdonough's squadron. She should certainly have been a match for the Wolfe and Melville together, and the Madison and Oneida for the Royal George and Sydney Smith. In fact, the three heavy American vessels ought to have been an overmatch for the four heaviest of the British squadron, although these possessed the nominal superiority. And in ordinary cases the eight remaining American gun-vessels would certainly seem to be an overmatch for the two British schooners, but it is just here that the difficulty of comparing the forces comes in. When the water was very smooth and the wind light, the long 32's and 24's of the Americans could play havoc with the British schooners, at a distance which would render the carronades of the latter useless. But the latter were built for war, possessed quarters and were good cruisers, while Chauncy's schooners were merchant vessels, without quarters, crank, and so loaded down with heavy metal that whenever it blew at all hard they could with difficulty be kept from upsetting, and ceased to be capable even of defending themselves. When Sir James Yeo captured two of them he would not let them cruise with his other vessels at all, but sent them back to act as gun-boats, in which capacity they were serving when recaptured; this is a tolerable test of their value compared to their opponents. Another disadvantage that Chauncy had to contend with, was the difference in the speed of the various vessels. The Pike and Madison were fast, weatherly ships; but the Oneida was a perfect slug, even going free, and could hardly be persuaded to beat to windward at all. In this respect Yeo was much better off; his six ships were regular men-of-war, with quarters, all of them seaworthy, and fast enough to be able to act with uniformity and not needing to pay much regard to the weather. His force could act as a unit; but Chauncy's could not. Enough wind to make a good working breeze for his larger vessels put all his smaller ones hors de combat: and in weather that suited the latter, the former could not move about at all. When speed became necessary the two ships left the brig hopelessly behind, and either had to do without her, or else perhaps let the critical moment slip by while waiting for her to come up. Some of the schooners sailed quite as slowly; and finally it was found out that the only way to get all the vessels into action at once was to have one half the fleet tow the other half. It was certainly difficult to keep the command of the lake when, if it came on to blow, the commodore had to put into port under penalty of seeing a quarter of his fleet founder before his eyes. These conflicting considerations render it hard to pass judgment; but on the whole it would seem as if Chauncy was the superior in force, for even if his schooners were not counted, his three square-rigged vessels were at least a match for the four square-rigged British vessels, and the two British schooners would not have counted very much in such a conflict. In calm weather he was certainly the superior. This only solves one of the points in which the official letters of the two commanders differ: after every meeting each one insists that he was inferior in force, that the weather suited his antagonist, and that the latter ran away, and got the worst of it; all of which will be considered further on.