полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

[Illustration: Captain James Lawrence: a portrait by Gilbert Stuart painted in Boston in 1812, shortly before Lawrence's promotion to captain, showing him wearing the single epaulet of a master commandant. (Courtesy U.S. Naval Academy Museum) ]

To return now to the Hornet. This vessel had continued blockading the Bonne Citoyenne until January 24th, when the Montagu, 74, arrived toward evening and chased her into port. As the darkness came on the Hornet wore, stood out to sea, passing into the open without molestation from the 74, and then steered toward the northeast, cruising near the coast, and making a few prizes, among which was a brig, the Resolution, with $23,000 in specie aboard, captured on February 14th. On the 24th of February, while nearing the mouth of the Demerara River, Captain Lawrence discovered a brig to leeward, and chased her till he ran into quarter less five, when, having no pilot, he hauled off-shore. Just within the bar a man-of-war brig was lying at anchor; and while beating round Caroband Bank, in order to get at her, Captain Lawrence discovered another sail edging down on his weather-quarter. [Footnote: Letter of Captain Lawrence, March 29, 1813.] The brig at anchor was the Espiègle, of 18 guns, 32-pound carronades, Captain John Taylor [Footnote: James, vi, 278.]; and the second brig seen was the Peacock, Captain William Peake, [Footnote: Do.] which, for some unknown reason, had exchanged her 32-pound carronades for 24's. She had sailed from the Espiègle's anchorage the same morning at 10 o'clock. At 4.20 P.M. the Peacock hoisted her colors; then the Hornet beat to quarters and cleared for action. Captain Lawrence kept close by the wind, in order to get the weather-gage; when he was certain he could weather the enemy, he tacked, at 5.10, and the Hornet hoisted her colors. The ship and the brig now stood for each other, both on the wind, the Hornet being on the starboard and the Peacock on the port tack, and at 5.25 they exchanged broadsides, at half pistol-shot distance, while going in opposite directions, the Americans using their lee and the British their weather battery. The guns were fired as they bore, and the Peacock suffered severely, while her antagonist's hull was uninjured, though she suffered slightly aloft and had her pennant cut off by the first shot fired. [Footnote: Cooper, p. 200.] One of the men in the mizzen-top was killed by a round shot, and two more were wounded in the main-top. [Footnote: See entry in her log for this day (In "Log-Book of Hornet, Wasp, and Argus, from July 20, 1809, to October 6, 1813,") in the Bureau of Navigation, at Washington.] As soon as they were clear, Captain Peake put his helm hard up and wore, firing his starboard guns; but the Hornet had watched him closely, bore up as quickly, and coming down at 5.35, ran him close aboard on the starboard quarter. Captain Peake fell at this moment, together with many of his crew, and, unable to withstand the Hornet's heavy fire, the Peacock surrendered at 5.39, just 14 minutes after the first shot; and directly afterward hoisted her ensign union down in the forerigging as a signal of distress. Almost immediately her main-mast went by the board. Both vessels then anchored, and Lieutenant J. T Shubrick, being sent on board the prize, reported her sinking. Lieutenant D. Connor was then sent in another boat to try to save the vessel; but though they threw the guns overboard, plugged the shot holes, tried the pumps, and even attempted bailing, the water gained so rapidly that the Hornet's officers devoted themselves to removing the wounded and other prisoners; and while thus occupied the short tropical twilight left them. Immediately afterward the prize settled, suddenly and easily, in 51/2 fathoms water, carrying with her three of the Hornet's people and nine of her own, who were rummaging below; meanwhile four others of her crew had lowered her damaged stern boat, and in the confusion got off unobserved and made their way to the land. The foretop still remained above water, and four of the prisoners saved themselves by running up the rigging into it. Lieutenant Connor and Midshipman Cooper (who had also come on board) saved themselves, together with most of their people and the remainder of the Peacock's crew, by jumping into the launch, which was lying on the booms, and paddling her toward the ship with pieces of boards in default of oars.

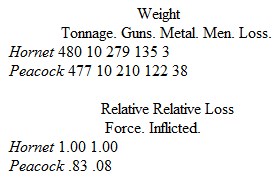

The Hornet's complement at this time was 150, of whom she had 8 men absent in a prize and 7 on the sick list, [Footnote: Letter of Captain Lawrence.] leaving 135 fit for duty in the action; [Footnote: Letter of Lieutenant D. Connor, April 26, 1813] of these one man was killed, and two wounded, all aloft. Her rigging and sails were a good deal cut, a shot had gone through the foremast, and the bowsprit was slightly damaged; the only shot that touched her hull merely glanced athwart her bows, indenting a plank beneath the cat-head. The Peacock's crew had amounted to 134, but 4 were absent in a prize, and but 122 [Footnote: Letter of Lieutenant F. W. Wright (of the Peacock), April 17, 1813.] fit for action; of these she lost her captain, and seven men killed and mortally wounded, and her master, one midshipman, and 28 men severely and slightly wounded,—in all 8 killed and 30 wounded, or about 13 times her antagonist's loss. She suffered under the disadvantage of light metal, having 24's opposed to 32's; but judging from her gunnery this was not much of a loss, as 6-pounders would have inflicted nearly as great damage. She was well handled and bravely fought; but her men showed a marvellous ignorance of gunnery. It appears that she had long been known as "the yacht," on account of the tasteful arrangement of her deck; the breechings of the carronades were lined with white canvas, and nothing could exceed in brilliancy the polish upon the traversing bars and elevating screws. [Footnote: James, vi, 280.] In other words, Captain Peake had confounded the mere incidents of good discipline with the essentials. [Footnote: Codrington ("Memoirs," i. 310) comments very forcibly on the uselessness of a mere martinet.]

The Hornet's victory cannot be regarded in any other light than as due, not to the heavier metal, but to the far more accurate firing of the Americans; "had the guns of the Peacock been of the largest size they could not have changed the result, as the weight of shot that do not hit is of no great moment." Any merchant-ship might have been as well handled and bravely defended as she was; and an ordinary letter-of-marque would have made as creditable a defence.

During the entire combat the Espiégle was not more than 4 miles distant and was plainly visible from the Hornet; but for some reason she did not come out, and her commander reported that he knew nothing of the action till the next day. Captain Lawrence of course was not aware of this, and made such exertions to bend on new sails, stow his boats, and clear his decks that by nine o'clock he was again prepared for action, [Footnote: Letter of Captain Lawrence.] and at 2 P.M. got underway for the N.W. Being now overcrowded with people and short of water he stood for home, anchoring at Holmes' Hole in Martha's Vineyard on the 19th of March.

On their arrival at New York the officers of the Peacock published a card expressing in the warmest terms their appreciation of the way they and their men had been treated. Say they: "We ceased to consider ourselves prisoners; and every thing that friendship could dictate was adopted by you and the officers of the Hornet to remedy the inconvenience we would otherwise have experienced from the unavoidable loss of the whole of our property and clothes owing to the sudden sinking of the Peacock." [Footnote: Quoted in full in "Niles' Register" and Lossing's "Field Book."] This was signed by the first and second lieutenants, the master, surgeon and purser.

[Illustration of Peacock and Hornet action from 5.10 to 5.35.]

That is, the forces standing nearly as 13 is to 11, the relative execution was about as 13 is to 1.

The day after the capture Captain Lawrence reported 277 souls aboard, including the crew of the English brig Resolution which he had taken, and of the American brig Hunter, prize to the Peacock. As James, very ingeniously, tortures these figures into meaning what they did not, it may be well to show exactly what the 277 included. Of the Hornet's original crew of 150, 8 were absent in a prize, 1 killed, and 3 drowned, leaving (including 7 sick) 138; of the Peacock's original 134, 4 were absent in a prize, 5 killed, 9 drowned, and 4 escaped, leaving (including 8 sick and 3 mortally wounded) 112; there were also aboard 16 other British prisoners, and the Hunter's crew of 11 men—making just 277. [Footnote: The 277 men were thus divided into: Hornet's crew, 138; Peacock's crew, 112; Resolution's crew, 16; Hunter's crew, 11. James quotes "270" men, which he divides as follows: Hornet 160, Peacock 101, Hunter 9,—leaving out the Resolution's crew, 11 of the Peacock's, and 2 of the Hunter's.] According to Lieutenant Connor's letter, written in response to one from Lieutenant Wright, there were in reality 139 in the Peacock's crew when she began action; but it is, of course, best to take each commander's account of the number of men on board his ship that were fit for duty.

On Jan. 17th the Viper, 12, Lieutenant J. D. Henly was captured by the British frigate Narcissus, 32, Captain Lumly.

On Feb. 8th, while a British squadron, consisting of the four frigates Belvidera (Captain Richard Byron), Maidstone, Junon, and Statira, were at anchor in Lynhaven Bay, a schooner was observed in the northeast standing down Chesapeake Bay. [Footnote: James, vi, 325.] This was the Lottery, letter-of-marque, of six 12-pounder carronades and 25 men, Captain John Southcomb, bound from Baltimore to Bombay. Nine boats, with 200 men, under the command of Lieutenant Kelly Nazer were sent against her, and, a calm coming on, overtook her. The schooner opened a well-directed fire of round and grape, but the boats rushed forward and boarded her, not carrying her till after a most obstinate struggle, in which Captain Southcomb and 19 of his men, together with 13 of the assailants, were killed or wounded. The best war ship of a regular navy might be proud of the discipline and courage displayed by the captain and crew of the little Lottery. Captain Byron on this, as well as on many another occasion, showed himself to be as humane as he was brave and skilful. Captain Southcomb, mortally wounded, was taken on board Byron's frigate, where he was treated with the greatest attention and most delicate courtesy, and when he died his body was sent ashore with every mark of the respect due to so brave an officer. Captain Stewart (of the Constellation) wrote Captain Byron a letter of acknowledgment for his great courtesy and kindness. [Footnote: The correspondence between the two captains is given in full in "Niles' Register," which also contains fragmentary notes on the action, principally as to the loss incurred.]

On March 16th a British division of five boats and 105 men, commanded by Lieutenant James Polkinghorne, set out to attack the privateer schooner Dolphin of 12 guns and 70 men, and the letters-of-marque, Racer, Arab, and Lynx, each of six guns and 30 men. Lieutenant Polkinghorne, after pulling 15 miles, found the four schooners all prepared to receive him, but in spite of his great inferiority in force he dashed gallantly at them. The Arab and Lynx surrendered at once; the Racer was carried after a sharp struggle in which Lieutenant Polkinghorne was wounded, and her guns turned on the Dolphin. Most of the latter's crew jumped overboard; a few rallied round their captain, but they were at once scattered as the British seamen came aboard. The assailants had 13, and the privateersmen 16 men killed and wounded in the fight. It was certainly one of the most brilliant and daring cutting-out expeditions that took place during the war, and the victors well deserved their success. The privateersmen (according to the statement of the Dolphin's master, in "Niles' Register") were panic-struck, and acted in any thing but a brave manner. All irregular fighting-men do their work by fits and starts. No regular cruisers could behave better than did the privateers Lottery, Chasseur, and General Armstrong; none would behave as badly as the Dolphin, Lynx, and Arab. The same thing appears on shore. Jackson's irregulars at New Orleans did as well, or almost as well, as Scott's troops at Lundy's Lane; but Scott's troops would never have suffered from such a panic as overcame the militia at Bladensburg.

On April 9th the schooner Norwich, of 14 guns and 61 men, Sailing-master James Monk, captured the British privateer Caledonia, of 10 guns and 41 men, after a short action in which the privateer lost 7 men.

On April 30th Commodore Rodgers, in the President. 44, accompanied by Captain Smith in the Congress, 38, sailed on his third cruise. [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Rodgers, Sept. 30, 1813.] On May 2d he fell in with and chased the British sloop Curlew, 18, Captain Michael Head, but the latter escaped by knocking away the wedges of her masts and using other means to increase her rate of sailing. On the 8th, in latitude 39° 30' N., long. 60° W., the Congress parted company, and sailed off toward the southeast, making four prizes, of no great value, in the North Atlantic; [Footnote: Letter of Captain Smith, Dec. 15, 1813.] when about in long. 35 ° W. she steered south, passing to the south of the line. But she never saw a man-of-war, and during the latter part of her cruise not a sail of any kind; and after cruising nearly eight months returned to Portsmouth Harbor on Dec. 14th, having captured but four merchant-men. Being unfit to cruise longer, owing to her decayed condition, she was disarmed and laid up; nor was she sent to sea again during the war. [Footnote: James states that she was "blockaded" in port by the Tenedos, during part of 1814; but was too much awed by the fate of the Chesapeake to come out during the "long blockade" of Captain Parker. Considering the fact that she was too decayed to put to sea, had no guns aboard, no crew, and was, in fact, laid up, the feat of the Tenedos was not very wonderful; a row-boat could have "blockaded" her quite as well. It is worth noticing, as an instance of the way James alters a fact by suppressing half of it.]

Meanwhile Rodgers cruised along the eastern edge of the Grand Bank until he reached latitude 48°, without meeting any thing, then stood to the southeast, and cruised off the Azores till June 6th. Then he crowded sail to the northeast after a Jamaica fleet of which he had received news, but which he failed to overtake, and on June 13th, in lat. 46°, long. 28°, he gave up the chase and shaped his course toward the North Sea, still without any good luck befalling him. On June 27th he put into North Bergen in the Shetlands for water, and thence passed the Orkneys and stretched toward the North Cape, hoping to intercept the Archangel fleet. On July 19th, when off the North Cape, in lat. 71° 52' N., long. 20° 18' E., he fell in with two sail of the enemy, who made chase; after four days' pursuit the commodore ran his opponents out of sight. According to his letter the two sail were a line-of-battle ship and a frigate; according to James they were the 12-pounder frigate Alexandria, Captain Cathcart, and Spitfire, 16, Captain Ellis. James quotes from the logs of the two British ships, and it would seem that he is correct, as it would not be possible for him to falsify the logs so utterly. In case he is true, it was certainly carrying caution to an excessive degree for the commodore to retreat before getting some idea of what his antagonists really were. His mistaking them for so much heavier ships was a precisely similar error to that made by Sir George Collier and Lord Stuart at a later date about the Cyane and Levant. James wishes to prove that each party perceived the force of the other, and draws a contrast (p. 312) between the "gallantry of one party and pusillanimity of the other." This is nonsense, and, as in similar cases, James overreaches himself by proving too much. If he had made an 18-pounder frigate like the Congress flee from another 18-pounder, his narrative would be within the bounds of possibility and would need serious examination. But the little 12-pounder Alexandria, and the ship-sloop with her 18-pound carronades, would not have stood the ghost of a chance in the contest. Any man who would have been afraid of them would also have been afraid of the Little Belt, the sloop Rodgers captured before the war. As for Captains Cathcart and Ellis, had they known the force of the President, and chased her with a view of attacking her, their conduct would have only been explicable on the ground that they were afflicted with emotional insanity.

The President now steered southward and got into the mouth of the Irish Channel; on August 2d she shifted her berth and almost circled Ireland; then steered across to Newfoundland, and worked south along the coast. On Sept. 23d, a little south of Nantucket, she decoyed under her guns and captured the British schooner Highflyer, 6, Lieut. William Hutchinson, and 45 men; and went into Newport on the 27th of the same month, having made some 12 prizes.

On May 24th Commodore Decatur in the United States, which had sent ashore six carronades, and now mounted but 48 guns, accompanied by Captain Jones in the Macedonian, 38, and Captain Biddle in the Wasp, 20, left New York, passing through Hell Gate, as there was a large blockading force off the Hook. Opposite Hunter's Point the main-mast of the States was struck by lightning, which cut off the broad pendant, shot down the hatchway into the doctor's cabin, put out his candle, ripped up the bed, and entering between the skin and ceiling of the ship tore off two or three sheets of copper near the waterline, and disappeared without leaving a trace! The Macedonian, which was close behind, hove all aback, in expectation of seeing the States blown up.

At the end of the sound Commodore Decatur anchored to watch for a chance of getting out. Early on June 1st he started; but in a couple of hours met the British Captain R. D. Oliver's squadron, consisting of a 74, a razee, and a frigate. These chased him back, and all his three ships ran into New London. Here, in the mud of the Thames river, the two frigates remained blockaded till the close of the war; but the little sloop slipped out later, to the enemy's cost.

We left the Chesapeake, 38, being fitted out at Boston by Captain James Lawrence, late of the Hornet. Most of her crew, as already stated, their time being up, left, dissatisfied with the ship's ill luck, and angry at not having received their due share of prize-money. It was very hard to get sailors, most of the men preferring to ship in some of the numerous privateers where the discipline was less strict and the chance of prize-money much greater. In consequence of this an unusually large number of foreigners had to be taken, including about forty British and a number of Portuguese. The latter were peculiarly troublesome; one of their number, a boatswain's mate, finally almost brought about a mutiny among the crew which was only pacified by giving the men prize-checks. A few of the Constitution's old crew came aboard, and these, together with some of the men who had been on the Chesapeake during her former voyage, made an excellent nucleus. Such men needed very little training at either guns or sails; but the new hands were unpractised, and came on board so late that the last draft that arrived still had their hammocks and bags lying in the boats stowed over the booms when the ship was captured. The officers were largely new to the ship, though the first lieutenant, Mr. A. Ludlow, had been the third in her former cruise; the third and fourth lieutenants were not regularly commissioned as such, but were only midshipmen acting for the first time in higher positions. Captain Lawrence himself was of course new to all, both officers and crew. [Footnote: On the day on which he sailed to attack the Shannon, Lawrence writes to the Secretary of the Navy as follows: "Lieutenant Paige is so ill as to be unable to go to sea with the ship. At the urgent request of Acting-Lieutenant Pierce I have granted him, also, permission to go on shore; one inducement for my granting his request was his being at variance with every officer in his mess." "Captains' Letters," vol. 29, No. 1, in the Naval Archives at Washington. Neither officers nor men had shaken together.] In other words, the Chesapeake possessed good material, but in an exceedingly unseasoned state.

Meanwhile the British frigate Shannon, 38, Captain Philip Bowes Vere Broke, was cruising off the mouth of the harbor. To give some idea of the reason why she proved herself so much more formidable than her British sister frigates it may be well to quote, slightly condensing, from James:

"There was another point in which the generality of British crews, as compared with any one American crew, were miserably deficient; that is, skill in the art of gunnery. While the American seamen were constantly firing at marks, the British seamen, except in particular cases, scarcely did so once in a year; and some ships could be named on board which not a shot had been fired in this way for upward of three years. Nor was the fault wholly the captain's. The instructions under which he was bound to act forbade him to use, during the first six months after the ship had received her armament, more shots per month than amounted to a third in number of the upper-deck guns; and, after these six months, only half the quantity. Many captains never put a shot in the guns till an enemy appeared; they employed the leisure time of the men in handling the sails and in decorating the ship. Captain Broke was not one of this kind. From the day on which he had joined her, the 14th of September, 1806, the Shannon began to feel the effect of her captain's proficiency as a gunner and zeal for the service. The laying of the ship's ordnance so that it may be correctly fired in a horizontal direction is justly deemed a most important operation, as upon it depends in a great measure the true aim and destructive effect of the shot; this was attended to by Captain Broke in person. By draughts from other ships, and the usual means to which a British man-of-war is obliged to resort, the Shannon got together a crew; and in the course of a year or two, by the paternal care and excellent regulations of Captain Broke, the ship's company became as pleasant to command as it was dangerous to meet." The Shannon's guns were all carefully sighted, and, moreover, "every day, for about an hour and a half in the forenoon, when not prevented by chase or the state of the weather, the men were exercised at training the guns, and for the same time in the afternoon in the use of the broadsword, pike, musket, etc. Twice a week the crew fired at targets, both with great guns and musketry; and Captain Broke, as an additional stimulus beyond the emulation excited, gave a pound of tobacco to every man that put a shot through the bull's eye." He would frequently have a cask thrown overboard and suddenly order some one gun to be manned to sink the cask. In short, the Shannon was very greatly superior, thanks to her careful training, to the average British frigate of her rate, while the Chesapeake, owing to her having a raw and inexperienced crew, was decidedly inferior to the average American frigate of the same strength.