полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

During those days and nights Augustus gave evidence of a truly remarkable strength of mind and body, never missing a ceremony, and himself performing the sacrifices. Agrippa showed less power of endurance than his friend and master. He appeared only in the daytime, helping the emperor in addressing supplications to the gods, and in immolating the victims.

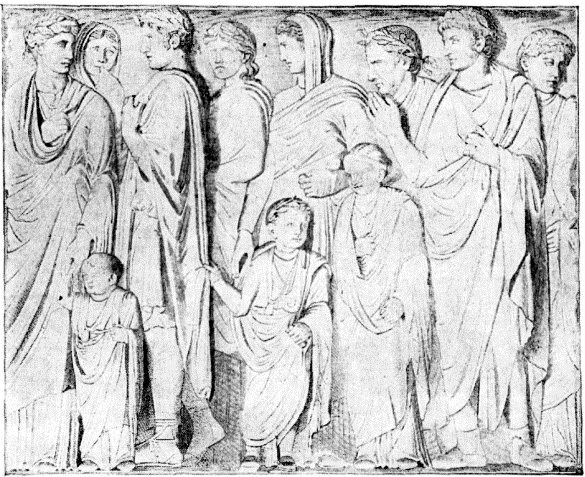

Ara Pacis Augustae. Among the honors voted to Augustus by the Senate in the year 13 b. c., on the occasion of his triumphal return from the campaigns of Germany and Gaul, was the erection of a votive altar in the Curia itself. Augustus refused it, but consented that an altar should be raised in the Campus Martius and dedicated to Peace. Judging from the fragments which have come down to us, this ara was one of the most exquisite artistic productions of the golden age of Augustus. It stood in the centre of a triple square enclosure, on the west side of the Via Flaminia, the site of the present Palazzo Fiano. Twice its remains have been brought to light; once in 1554, when they were drawn by Giovanni Colonna,47 and again in 1859, when the present duke of Fiano was rebuilding the southern wing of the palace on the Via in Lucina. Of the panels and basreliefs found in 1554, some were removed to the Villa Medici and inserted in the front of the casino, on the garden side; others were transferred to Florence; those of 1859 have been placed in the vestibule of the Palazzo Fiano. They are well worth a visit.

The family of Augustus. Relief from the Ara Pacis, in the Gallery of the Uffizi, Florence.

Ara Incendii Neroniani. In the month of July, a. d. 65, half Rome was destroyed by the fire of Nero. The citizens, overwhelmed by the greatness of the calamity, and ignorant of its true cause, made a vow for the annual celebration of expiatory sacrifices, on altars expressly constructed for the purpose in each of the fourteen regions of the metropolis. The vow was, however, forgotten until Domitian claimed its fulfilment some twenty or twenty-five years later. One of these altars, which adjoined Domitian's paternal house on the Quirinal, has just been found near the church of S. Andrea del Noviziato, in the foundations of the new "Ministero della Casa Reale."

The altar, six metres long by three wide, built of travertine with a coating of marble, stands in the middle of a paved area of considerable size. The area is lined with stone cippi, placed at an interval of two and a half metres from one another. The following inscription has been found engraved on two of them: "This sacred area, marked with stone cippi, and enclosed with a hedge, as well as the altar which stands in the middle of it, was dedicated by the emperor Domitian in consequence of an unfulfilled vow made by the citizens at the time of the fire of Nero. The dedication is made subject to the following rules: that no one shall be allowed to loiter, trade, build, or plant trees or shrubs within the line of terminal stones; that on August 23 of each year, the day of the Volkanalia, the magistrate presiding over this sixth region shall sacrifice on this altar a red calf and a pig; that he shall address to the gods the following prayer (text missing)." The inscription has been read twice: once towards the end of the fifteenth century, when the cippus containing it was removed to S. Peter's and made use of in the new building, and again in 1644, when Pope Barberini was laying the foundations of S. Andrea al Quirinale, one of the most graceful and pleasing churches of modern Rome.

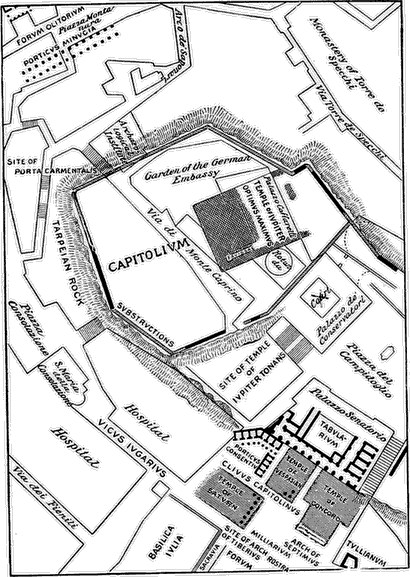

Let us now turn our attention to more imposing structures. The first temple in the excavation of which I took part was that of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill.48 Its discovery was due more to an intuition of the truth, than to actual recognition of existing remains. On November 7, 1875, while digging for the foundation of the new Rotunda in the garden which divides the Conservatori palace from that of the Caffarellis,—the residence of the German ambassador,—our workmen came upon a piece of a colossal fluted column of Pentelic marble, lying on a platform of squared stones, which were laid without mortar, in a decidedly archaic style. Were we in the presence of the remains of the famous Capitolium, or of one of the smaller temples within the Arx? To give this query a satisfactory answer, we must remember that the Capitoline Hill had two summits, one containing the citadel, or Arx, the other the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the Capitolium. Ancient writers never use the two names promiscuously, or apply them indifferently to either summit or to the whole hill. The name of the hill is the Capitoline; not the Capitol, which means exclusively the portion occupied by the great temple. Suffice it to quote Livy's evidence (vi. 20), ne quis in Arce aut Capitolio habitaret, and also the passage of Aulus Gellius (v. 12) in which the shrine of Vedjovis is placed between the Arx and the Capitolium.

For many generations topographers tried to discover which summit was occupied by the citadel, and which by the temple. The Italian school, save a few exceptions, had always identified the site of the Aracœli with that of the temple, the Caffarelli palace with that of the citadel. The Germans upheld the opposite theory. In these circumstances it is not surprising that the discovery made November 7, 1875, should have excited us; because we saw at once our chance of settling the dispute, not theoretically, but with the evidence of facts.

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, designed by Tarquinius Priscus, built by Tarquinius Superbus, and dedicated in 509 b. c. by the consul M. Horatius Pulvillus, stood on a high platform 207½ feet long, by 192½ feet broad. The front of the edifice, ornamented with three rows of columns, faced the south. The style of the architecture was purely Etruscan, and the intercolumniations were so wide as to require architraves of timber. The cella was divided into three sections, the middle one of which was sacred to Jupiter, that on the right to Minerva, that on the left to Juno Regina; the top of the pediment was ornamented with a terra-cotta quadriga. Of the same material was the statue of the god, with the face painted red, and the body dressed in a tunica palmata and a toga picta, the work of an Etruscan artist, Turianus of Fregenæ.

In 386 b. c. it was found necessary to enlarge the platform in the centre of which the temple stood; and as the hill was sloping, even precipitous, on three sides, it was necessary to raise huge foundation walls from the plain below to the level of the platform, a work described by Pliny (xxxvi. 15, 24) as prodigious, and by Livy (vi. 4) as one of the wonders of Rome.

THE WESTERN SUMMIT OF THE CAPITOLINE HILL (R. Lanciani del.)

On July 6, 83 b. c., four hundred and twenty-six years after its dedication by Horatius Pulvillus, an unknown malefactor, taking advantage of the abundance of timber used in the structure, set fire to it, and utterly destroyed the sanctuary which for four centuries had presided over the fates of the Roman Commonwealth. The incendiary, less fortunate than Erostratos, remained unknown, the suspicions cast at the time against Papirius Carbo, Scipio, Norbanus and Sulla having proved groundless. He probably belonged to the faction of Marius, because we know that Marius himself laid hands on the half-charred ruins of the temple, and pillaged several thousand pounds of gold.

Sulla the dictator undertook the reconstruction of the Capitolium, for which purpose he caused some columns of the temple of the Olympian Jupiter to be removed from Athens to Rome. Sulla's work was continued by Lutatius Catulus, and finished by Julius Cæsar in 46 b. c. A second restoration took place in the year 9 b. c. under Augustus, a third a. d. 74 under Vespasian, and the last in the year 82, under Domitian. It was therefore evident that, if the temple had not been literally obliterated since that time, its remains would show the characteristics of the age of Domitian, who is known to have made use of Pentelic marble in his reconstruction. We should also find these remains in the middle of a platform of the time of the kings, surrounded by foundation walls of the time of the republic. The accompanying plan shows how perfectly the remains discovered on the southwestern summit of the Capitoline Hill corresponded to this theory.

The platform, in the shape of a parallelogram, 183 feet broad and a few feet longer, is built of roughly squared blocks of capellaccio, exactly like certain portions of the Servian walls. Its area and height were reduced by one third, when the Caffarellis built their palace, in 1680. A sketch taken at that time by Fabretti and published in his volume "De Columna Trajana" shows that fourteen tiers of stone have disappeared. A portion of the same platform, discovered in 1865, by Herr Schloezer, Prussian minister to Pius IX., is represented on the next page.

The foundation walls, which Pliny and Livy enumerate among the wonders of Rome, have been, and are still being, discovered on the three sides of the hill which face the Piazza della Consolazione, the Piazza Montanara, and the Via di Torre de' Specchi. They are built of blocks of red tufa, with facing of travertine. The travertine facing is covered with inscriptions set up in honor of the great divinity of Rome by the kings and nations of the whole world. One cannot read these historical documents49 without acquiring a new sense of the magnitude and power of the city.

View of the Platform of the Temple of Jupiter.

These inscriptions are found mostly at the foot of the substructure, on the side towards the Piazza della Consolazione. The latest, found in the foundations of the Palazzo Moroni, contain messages of friendship and gratitude from kings Mithradates Philopator and Mithradates Philadelphos, of Pontus, from Ariobarzanes Philoromæus of Cappadocia and Athenais his queen, from the province of Lycia, from some townships of the province of Caria, etc.

As for the remains of the temple itself, the colossal column discovered November 7, 1875, in the Conservatori garden, is not the only one saved from the wreck. Flaminio Vacca, the sculptor and amateur-archæologist of the sixteenth century, says: "Upon the Tarpeian Rock, behind the Palazzo de' Conservatori, several pillars of Pentelic marble (marmo statuale) were lately found. Their capitals are so enormous that out of one of them I have carved the lion now in the Villa Medici. The others were used by Vincenzo de Rossi to carve the prophets and other statues which adorn the chapel of cardinal Cesi in the church of S. Maria della Pace. I believe the columns belonged to the Temple of Jupiter. No fragments of the entablature were found: but as the building was so close to the edge of the Tarpeian Rock, I suspect they must have fallen into the plain."

The correctness of this surmise is shown not only by the discovery of the dedicatory inscriptions, in the Piazza della Consolazione, just alluded to, but also from what took place in 1780, when the duca Lante della Rovere was excavating the foundations of a house, No. 13, Via Montanera. The discoveries are described by Montagnani as "marble entablatures of enormous size and beautiful workmanship, with festoons and bucranii in the frieze. No one took the trouble to sketch them; they were destroyed on the spot. I have no doubt that they belonged to the temple seen by Vacca on the Monte Tarpeo, one hundred and eighty-six years ago."

All these indications, compared with the discovery of the platform, the substructure, and the column of Pentelic marble in the Conservatori garden, leave no doubt as to the real position of the Temple of Jupiter. To that piece of marble we owe the opportunity and the privilege of settling a dispute on Roman topography which had lasted at least three centuries.

The temple, rebuilt by Domitian, stood uninjured till the middle of the fifth century. In June, 455, the Vandals, under Genseric, plundered the sanctuary, its statues were carried off to adorn the African residence of the king, and half the roof was stripped of its gilt bronze tiles. From that time the place was used as a stone-quarry and lime-kiln to such an extent that only the solitary fragment of a column remains on the spot to tell the long tale of destruction. Another piece of Pentelic marble was found January 24, 1889, near the Tullianum (S. Pietro in Carcere). It belongs to the top of a column, and has the same number of flutings,—twenty-four. This fragment seems to have been sawn on the spot to the desired length, seven feet, and then dragged down the hill towards some stone-cutter's shop. Why it was thus abandoned, half way, in a hollow or pit dug expressly for it, there is nothing to show.

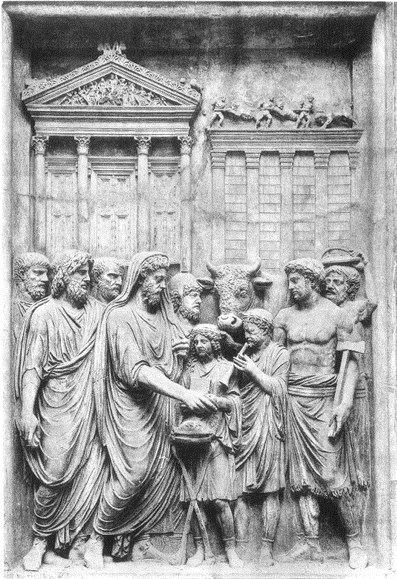

The Temple of Jupiter is represented in ancient monuments of the class called pictorial reliefs. I have selected for my illustration one of the panels from the triumphal arch of Marcus Aurelius, near S. Martina, because it contains a good sketch of the reliefs of the pediment, with Jupiter seated between Juno and Minerva. The temple itself is most carelessly drawn, the number of columns being reduced by one half, that is, from eight to four.50

PANEL FROM THE ARCH OF MARCUS AURELIUS

There is one interesting feature of the Capitolium, which is not well known among those who do not make a profession of archæology. It was used as a place for advertising State acts, deeds, and documents, in order that the public might take notice of them and be informed of what was going on in the administrative, military, and political departments. This fact is known from a clause appended to imperial letters-patent by which veterans were honorably discharged from the army or navy, and privileges bestowed on them in recognition of their services. These deeds, known as diplomata honestæ missionis, were engraved on bronze tablets shaped like the cover of a book, the original of which was hung somewhere in the Capitolium, and a copy taken by the veteran to his home. The originals are all gone, having fallen the prey of the plunderers of bronze in Rome, but copies are found in great numbers in every province of the Roman empire from which men were drafted.51 These copies end with the clause:—

"Transcribed (and compared or verified) from the original bronze tablet which is hung in Rome, in the Capitolium"—and here follows the designation of a special place of the Capitolium, such as,—

"On the right side of the shrine of the Fides populi romani" (December 11, a. d. 52).

"On the left side of the ædes Thensarum" (July 2, a. d. 60).

"On the pedestal of the statue of Quintus Marcius Rex, behind the temple of Jupiter" (June 15, 64).

"On the pedestal of the ara gentis Iuliæ, on the right side, the statue of Bacchus" (March 7, 71).

"On the vestibule, on the left wall, between the two archways" (May 21, 74).

"On the pedestal of the statue of Jupiter Africus" (December 2, 76).

"On the base of the column, on the inner side, near the statue of Jupiter Africus" (September 5, 85).

"On the tribunal by the trophies of Germanicus, which are near the shrine of the Fides" (May 15, 86).

Comparing these indications of localities with the dates of the diplomas,—there are sixty-three in all,—it appears that they were not hung at random, but in regular order from monument to monument, until every available space was covered. In the year 93 there was not an inch left, and the Capitol is mentioned no more as a place for exhibiting or advertising the acts of Government. From that year they were hung "in muro post templum divi ad Minervam," that is, behind the modern church of S. Maria Liberatrice.

The Temple of Isis and Serapis. In the spring of 1883, in surveying the tract of ground between the Collegio Romano and the Baths of Agrippa, formerly occupied by the Temple of Isis and Serapis, and in collecting archæological information concerning it, I was struck by the fact that, every time excavations were made on either side of the Via di S. Ignazio for building or restoring the houses which line it, remarkable specimens of Egyptian art had been brought to light. The annals of discoveries begin with 1374, when the obelisk now in the Piazza della Rotonda was found, under the apse of the church of S. Maria sopra Minerva, together with the one now in the Villa Mattei von Hoffman. In 1435, Eugenius IV. discovered the two lions of Nektaneb I. which are now in the Vatican, and the two of black basalt now in the Capitoline Museum. In 1440 the reclining figure of a river-god was found and buried again. The Tiber of the Louvre and the Nile of the Braccio Nuovo seem to have come to light during the pontificate of Leo X.; at all events it was he who caused them to be removed to the Vatican. In 1556 Giovanni Battista de Fabi found, and sold to cardinal Farnese, the reclining statue of Oceanus now in Naples. In 1719 the Isiac altar now in the Capitol was found under the Biblioteca Casanatense. In 1858 Pietro Tranquilli, in restoring his house,—the nearest to the apse of la Minerva,—came across the following-named objects: a sphinx of green granite, the head of which is a portrait of Queen Haths'epu, the oldest sister of Thothmes III., who was famous for her expedition to the Red Sea, recently described by Dümmichen;52 a sphinx of red granite, believed to be a Roman replica; a group of the cow Hathor, the living symbol of Isis, nursing the young Pharaoh Horemheb; the portrait statue of the grand dignitary Uahábra, a good specimen of Saïtic art; a column of the temple, covered with high reliefs, which represented a procession of bald-headed priests holding canopi in their hands; a capital, carved with papyrus leaves and lotus flowers; and a fragment of an Egyptian basrelief in red granite, with traces of polychromy.

In 1859 Augusto Silvestrelli, the owner of the next house, on the same side of the Via di S. Ignazio, found five capitals of the same style and size, which, I believe, are now in the Museo Etrusco Gregoriano. Inasmuch as no excavation had ever been made under the pavement of the street itself, which is public property, and as there was no reason why that strip of public property should not contain as many works of art as the houses about it, I asked the municipal authorities to try the experiment, and my proposal was accepted at once.

The Sphinx of Amasis.

The work began on Monday, June 11, 1883. It was difficult, because we had to dig to a depth of twenty feet between houses of very doubtful solidity. First to appear, at the end of the third day, was a magnificent sphinx of black basalt, the portrait of King Amasis. It is a masterpiece of the Saïtic school, perfected even in the smallest details, and still more impressive for its historical connection with the conquest of Egypt by Cambyses.

The cartouches bearing the king's name appear to have been purposely erased, though not so completely as to render the name illegible. The nose, likewise, and the uræus, the symbol of royalty, were hammered away at the same time. The explanation of these facts is given by Herodotos. When Cambyses conquered Saïs, Amasis had just been buried. The conqueror caused the body to be dragged out of the royal tomb, then flogged and otherwise insulted, and finally burnt, the maximum of profanation, from an Egyptian point of view. His name was erased from the monuments which bore it, as a natural consequence of the memoriæ damnatio. This sphinx is the surviving testimonial of the eventful catastrophe. When, six or seven centuries later, a Roman governor of Egypt, or a Roman merchant from the same province, singled out this work of art, to be shipped to Rome as a votive offering for the Temple of Isis, ignorant of the historical value of its mutilations, he had the nose and the uræus carefully restored. Now both are gone again, and there is no danger of a second restoration. I may remark, as a curious coincidence, that, as the name of Amasis is erased from the sphinx, so that of Hophries, his predecessor, is erased from the obelisk discovered in the same temple, and now in the Piazza della Minerva. In these two monuments of the Roman Iseum we possess a synopsis of Egyptian history between 595 and 526 b. c.

Obelisk of Rameses the Great.

The second work, discovered June 17, was an obelisk which was wonderfully well preserved to the very top of the pinnacle, and covered with hieroglyphics. It was quarried at Assuan, from a richly colored vein of red granite, and was brought to Rome, probably under Domitian, together with the obelisk now in the Piazza del Pantheon. The two monoliths are almost identical in size and workmanship, and are inscribed with the same cartouches of Rameses the Great. The one which I discovered was set up, in 1887, to the memory of our brave soldiers who fell at the battle of Dogali. The site selected for the monument, the square between the railway station and the Baths of Diocletian, is too large for such a comparatively small shaft.

Two days later, on the 19th, we discovered two kynokephaloi or kerkopithekoi, five feet high, carved in black porphyry. The monsters are sitting on their hind legs, with the paws of the forearms resting on the knees. Their bases contain finely-cut hieroglyphics, with the cartouche of King Necthor-heb, of the thirtieth Sebennitic dynasty. One of these kynokephaloi, and also the obelisk, were certainly seen in 1719 by the masons who built the foundations of the Biblioteca Casanatense. For some reason unknown to us, they kept their discovery a secret. Many other works of art were discovered before the close of the excavations, in the last days of June. Among them were a crocodile in red granite, the pedestal of a candelabrum, triangular in shape, with sphinxes at the corners; a column of the temple, with reliefs representing an Isiac procession; and a portion of a capital. From an architectural point of view, the most curious discovery was that the temple itself, with its colonnades and double cella, had been brought over, piece by piece, from the banks of the Nile to those of the Tiber. It is not an imitation; it is a purely original Egyptian structure, shaded first by the palm-trees of Saïs, and later by the pines of the Campus Martius.

The earliest trustworthy account we have of its existence is given by Flavius Josephus. He relates how Tiberius, after the assault of Mundus against Paulina,53 condemned the priests to crucifixion, burned the shrine, and threw the statue of the goddess into the Tiber. Nero restored the sanctuary; it was, however, destroyed again in the great conflagration, a. d. 80. Domitian was the second restorer; Hadrian, Commodus, Caracalla, and Alexander Severus improved and beautified the group, from time to time. At the beginning of the fourth century of our era it contained the propylaia, or pyramidal towers with a gateway, at each end of the dromos; one near the present church of S. Stefano del Cacco, one near the church of S. Macuto. They were flanked by one or more pairs of obelisks, of which six have been recovered up to the present time, namely, one now in the Piazza della Rotonda, a second in the Piazza della Minerva, a third in the Villa Mattei, a fourth in the Piazza della Stazione, a fifth in the Sphæristerion at Urbino, and fragments of a sixth in the Albani collection.

From the propylaia, a dromos, or sacred avenue, led to the double temple. To the dromos belong the two lions in the Museo Etrusco Gregoriano, the two lions in the Capitoline Museum, the sphinx of Queen Hathsèpu in the Barracco collection, the sphinx of Amasis and the Tranquilli sphinx in the Capitol, the cow Hathor and the statue of Uahábra in the Museo Archeologico in Florence, the kynokephaloi of Necthor-heb, the kynokephalos which gave the popular name of Cacco (ape) to the church of S. Stefano, the statue formerly in the Ludovisi Gallery, the Nile of the Braccio Nuovo, the Tiber of the Louvre, the Oceanus at Naples, the River-God buried in 1440, the Isiac altars of the Capitol and of the Louvre, the tripod, the crocodile and sundry other fragments which were found in 1883. Of the temple itself we possess two columns covered with mystic bas-reliefs, seven capitals,—one in the Capitol, the others in the Vatican,—and two blocks of granite from the walls of the cella, one in the Barberini gardens, one in the Palazzo Galitzin.