полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

A Granary of Ostia.

The grain was not intended to be sold, but to be distributed among the needy; the act of Sabinianus was, therefore, strongly censured, as being in strong contrast to the generosity of Gregory the Great. A legend on this subject is related by Paulus Diaconus in chapter xxix. of the Life of Gregory. He says that Gregory appeared thrice to Sabinianus, in a vision, entreating him to be more generous; and having failed to move him by friendly advice, he struck him dead. The price of one solidus for thirty modii is almost exorbitant; grain cost exactly one half this at the time of Theodoric.

The institution has outlived all the vicissitudes of the Middle Ages. Gregory XIII., in 1566, Paul V., in 1609, Clement XI., in 1705, re-opened the horrea ecclesiæ in the ruined halls of the Baths of Diocletian; and Clement XIII. added a wing to them, for the storage of oil. These buildings are still in existence around the Piazza di Termini, although devoted to other purposes.

It would be impossible to follow in all its manifestations the material and moral transformation of Rome from the third to the sixth centuries, without going beyond the limits of a single chapter.

The customs and practices of the classical age were so deeply rooted among the citizens that even now, after a lapse of sixteen centuries, they are noticeable to a great extent. When we read, for instance, of Popes elected by the people assembled at the Rostra,32 such as Stephen III., in 768, we must regard the circumstance as caused by a remembrance of past ages. Under the pontificate of Innocent II. (1130), of Eugenius III. (1145-1150), and of Lucius III. (1181-1185) the senators, or municipal magistrates, used to sit and administer justice in S. Martina and S. Adriano, that is, in the classic Roman Curia. Many other details will be incidentally described in the following chapters. I close the present one by referring to a graceful custom, borrowed likewise from the classic world,—the use of roses in church or funeral ceremonies and in social life.

The ancients celebrated, in the month of May, a feast called rosaria, in which sepulchres were profusely decorated with the favorite flower of the season. Roses were also used on occasions of public rejoicing. A Greek inscription, discovered by Fränkel at Pergamon, mentions, among the honors shown to the emperor Hadrian, the Rhodismos, which is interpreted as a scattering of roses. Traces of the custom are found in more recent times. In the Illyrian peninsula, and on the banks of the Danube, the country people, still feeling the influence of Roman civilization, celebrated feasts of flowers in spring and summer, under the name of rousalia. In the sixth century, when the Slavs were vacillating between the influence of the past and the present, the celebration of the Pentecost was mixed up with that of the half-pagan, half-barbarous rousalia. Southern Russians believe in supernatural female beings, called Rusalky, who bring prosperity to the fields and forests, which they have inhabited as flowers.

The early Christians decorated the sepulchres of martyrs and confessors, on the anniversary of their interment, with roses, violets, amaranths, and evergreens; and they celebrated the rosationes on the name-days of churches and sanctuaries. Wreaths and crowns of roses are often engraved on tombstones, hanging from the bills of mystic doves. The symbol refers more to the joys of the just in the future life than to the fleeting pleasures of the earth. The Acts of Perpetua relate a legend on this subject; that Saturus had a vision in the dungeon in which he was awaiting his martyrdom, in which he saw himself transported with Perpetua to a heavenly garden, fragrant with roses, and turning to his fair companion, he exclaimed: "Here we are in possession of that which our Lord promised!"

Roses and other flowers are painted on the walls of historical cubiculi. In a fresco of the crypts of Lucina, in the Catacombs of Callixtus, are painted birds, symbolizing souls who have been separated from their bodies, and are playing in fields of roses around the Tree of Life. As the word Paradeisos signifies a garden, so its mystic representation always takes the form of a delightful field of flowers and fruit. Dante gives to the seat of the blessed the shape of a fair rose, inside of which a crowd of angels with golden wings descend and return to the Lord:—

"Nel gran fior discendeva, che s'adornaDi tante foglie: e quindi risaliva,Là dove lo suo amor sempre soggiorna."33 Paradiso, xxxi. 10-12.Possibly it is from this allegory of paradise that the rite of the "golden rose" which the Pope blesses on Quadragesima Sunday is derived. The ceremony is very ancient, although the first mention of it appears only in the life of Leo IX. (1049-1055); and I may mention, as a curious coincidence, that the kings and queens of Navarre, their sons, and the dukes and peers of the realm, were bound to offer roses to the Parliament at the return of spring.

Roses played such an important part in church ceremonies that we find a fundus rosarius given as a present by Constantine to Pope Mark. The rosaria outlived the suppression of pagan superstitions, and by and by assumed its Christian form in the feast of Pentecost, which falls in the month of May. In that day roses were thrown from the roofs of churches on the worshipers below. The Pentecost is still called by the Italians Pasqua rosa.

CHAPTER II.

PAGAN SHRINES AND TEMPLES

Ancient temples as galleries of art.—The adornment of statues with jewelry, etc.—Offerings and sacrifices by individuals.—Stores of ex-votos found in the favissæ or vaults of temples.—Instances of these brought to light within recent years.—Remarkable wealth of one at Veii.—The altars of ancient Rome.—The ara maxima Herculis.—The Roma Quadrata.—The altar of Aius Locutius.—That of Dis and Proserpina.—Its connection with the Sæcular Games.—The discovery of the inscription describing these, in 1890.—The ara pacis Augustæ.—The ara incendii Neroniani.—Temples excavated in my time.—That of Jupiter Capitolinus.—History of its ruins.—The Capitol as a place for posting official announcements.—The Temple of Isis and Serapis.—The number of sculptures discovered on its site.—The Temple of Neptune.—Its remains in the Piazza di Pietra.—The Temple of Augustus.—The Sacellum Sanci.

Ancient guide-books of Rome, published in the middle of the fourth century,34 mention four hundred and twenty-four temples, three hundred and four shrines, eighty statues of gods, of precious metal, sixty-four of ivory, and three thousand seven hundred and eighty-five miscellaneous bronze statues. The number of marble statues is not given. It has been said, however, that Rome had two populations of equal size, one alive, and one of marble.

I have had the opportunity of witnessing or conducting the discovery of several temples, altars, shrines, and bronze statues. The number of marble statues and busts discovered in the last twenty-five years, either in Rome or the Campagna, may be stated at one thousand.

Before beginning the description of these beautiful monuments, I must allude to some details concerning the management and organization of ancient places of worship, upon which recent discoveries have thrown a considerable, and in some cases, unexpected light.

Roman temples, like the churches of the present day, were used not only as places of worship, but as galleries of pictures, museums of statuary, and "cabinets" of precious objects. In chapter v. of "Ancient Rome," I have given the catalogue of the works of art displayed in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine. The list includes: The Apollo and Artemis driving a quadriga, by Lysias; fifty statues of the Danaids; fifty of the sons of Egypt; the Herakles of Lysippos; Augustus with the attributes of Apollo (a bronze statue fifty feet high); the pediment of the temple, by Bupalos and Anthermos; statues of Apollo, by Skopas; Leto, by Kephisodotos, son of Praxiteles; Artemis, by Timotheos; and the nine Muses; also a chandelier, formerly dedicated by Alexander the Great at Kyme; medallions of eminent men; a collection of gold plate; another of gems and intaglios; ivory carvings; specimens of palæography; and two libraries.

Entablature of the Temple of Concord.

The Temple of Apollo was by no means the only sacred museum of ancient Rome; there were scores of them, beginning with the Temple of Concord, so emphatically praised by Pliny. This temple, built by Camillus, at the foot of the Capitol, and restored by Tiberius and Septimius Severus, was still standing at the time of Pope Hadrian I. (772-795), when the inscription on its front was copied for the last time by the Einsiedlensis. It was razed to the ground towards 1450. "When I made my first visit to Rome," says Poggio Bracciolini, "I saw the Temple of Concord almost intact (ædem fere integram), built of white marble. Since then the Romans have demolished it, and turned the structure into a lime-kiln." The platform of the temple and a few fragments of its architectural decorations were discovered in 1817. The reader may appreciate the grace of these decorations, from a fragment of the entablature now in the portico of the Tabularium, and one of the capitals of the cella, now in the Palazzo dei Conservatori. The cella contained one central and ten side niches, in which eleven masterpieces of Greek chisels were placed, namely, the Apollo and Hera, by Baton; Leto nursing Apollo and Artemis, by Euphranor; Asklepios and Hygieia, by Nikeratos; Ares and Hermes, by Piston; and Zeus, Athena, and Demeter, by Sthennis. The name of the sculptor of the Concordia in the apse is not known. Pliny speaks also of a picture by Theodoros, representing Cassandra; of four elephants, cut in obsidian, a miracle of skill and labor, and of a collection of precious stones, among which was the sardonyx set in the legendary ring of Polykrates of Samos. Most of these treasures had been offered to the goddess by Augustus, moved by the liberality which Julius Cæsar had shown towards his ancestral goddess, Venus Genetrix. We know from Pliny, xxxv. 9, that Cæsar was the first to give due honor to paintings, by exhibiting them in his Forum Julium. He gave about $72,000 (eighty talents), for two works of Timomachos, representing Medea and Ajax. At the base of the Temple of Venus Genetrix he placed his own equestrian statue, the horse of which, modelled by Lysippos, had once supported the figure of Alexander the Great. The statue of Venus was the work of Arkesilaos, and her breast was covered with strings of British pearls. Pliny (xxxvii. 5), after mentioning the collection of gems made by Scaurus, and another made by Mithradates, which Pompey the Great had offered to Jupiter Capitolinus, adds: "These examples were surpassed by Cæsar the dictator, who offered to Venus Genetrix six collections of cameos and intaglios."

A descriptive catalogue of these valuables and works of art was kept in each temple, and sometimes engraved on marble. The inventories included also the furniture and properties of the sacristy. In 1871 the following remarkable document was discovered in the Temple of Diana Nemorensis. The inventory, engraved on a marble pillar three feet high, is now preserved in the Orsini Castle at Nemi. It has been published by Henzen in "Hermes," vol. vi. p. 8, and reads as follows, in translation:—

Objects offered to [or belonging to] both temples [the temple of Isis and that of Bubastis]:—Seventeen statues; one head of the Sun; four silver images; one medallion; two bronze altars; one tripod (in the shape of one at Delphi); a cup for libations; a patera; a diadem [for the statue of the goddess] studded with gems; a sistrum of gilded silver; a gilt cup; a patera ornamented with ears of corn; a necklace studded with beryls; two bracelets with gems; seven necklaces with gems; nine ear-rings with gems; two nauplia [rare shells from the Propontis]; a crown with twenty-one topazes and eighty carbuncles; a railing of brass supported by eight hermulæ; a linen costume comprising a tunica, a pallium, a belt, and a stola, all trimmed with silver; a like costume without trimming.

[Objects offered] to Bubastis:—A costume of purple silk; another of turquoise color; a marble vase with pedestal; a water jug; a linen costume with gold trimmings and a golden girdle; another of plain white linen.

The objects described in this catalogue did not belong to the Temple of Diana itself, one of the wealthiest in central Italy; but to two small shrines, of Isis and Bubastis, built by a devotee within the sacred enclosure, on the north side of the square.

The ancients displayed remarkably bad taste in loading the statues of their gods with precious ornaments, and in spoiling the beauty of their temples with hangings of every hue and description. A document published by Muratori35 speaks of a statue of Isis which was dedicated by a lady named Fabia Fabiana as a memorial to her deceased granddaughter Avita. The statue, cast in silver, weighed one hundred and twelve and a half pounds, and was muffled in ornaments and jewelry beyond conception. The goddess wore a diadem in which were set six pearls, two emeralds, seven beryls, one carbuncle, one hyacinthus, and two flint arrow-heads; also earrings with emeralds and pearls, a necklace composed of thirty-six pearls and eighteen emeralds, two clasps, two rings on the little finger, one on the third, one on the middle finger; and many other gems on the shoes, ankles, and wrists. Another inscription discovered at Constantine, Algeria, describes a statue of Jupiter dedicated in the Capitol of that city. The devotees had placed on his head an oak-wreath of silver, with thirty leaves and fifteen acorns; they had loaded his right hand with a silver disk, a Victory waving a palm-leaf, and a crown of forty leaves; and in the other had fastened a silver rod and other emblems.

The hangings and tinsel not only disfigured the interior of temples, but were a source of danger from their combustibility. When we hear of fires destroying the Pantheon in a. d. 110, the Temple of Apollo in 363, that of Venus and Rome in 307, and that of Peace in 191, we may assume that they were started and fed by the inflammable materials with which the interiors were filled. There is no other explanation to be given, inasmuch as the structures were fire-proof, with the exception of the roof. As for the disfiguration of sacred buildings with all sorts of hangings, it is enough to quote the words of Livy (xl. 51). "In the year of Rome, 574, the censors M. Fulvius Nobilior and M. Æmilius Lepidus restored the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol. On this occasion they removed from the columns all the tablets, medallions, and military flags omnis generis which had been hung against them."

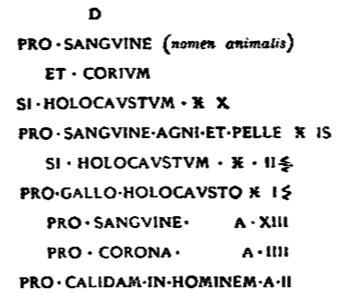

The right of performing sacrifices was sometimes granted to civilians, on payment of a fee. An inscription discovered among the ruins of the Temple of Malakbelos, outside the Porta Portese, on the site of the new railway station, relates how an importer of wine, Quintus Octavius Daphnicus, having built at his own expense a banqueting hall within the sacred enclosure, was rewarded with the immunitas sacrum faciendi, that is, the right of performing sacrifices without the assistance of priests. The performances were regulated by tariffs, which specified a price for every item; and one of these has actually survived to our day.36

The meaning of this tariff will be easily understood if we recall the details of a Græco-Roman sacrifice, in regard to the apportionment of the victim's flesh. The parts which were the perquisite of the priests differ in different worships; sometimes we hear of legs and skin, sometimes of tongue and shoulder. In the case of private sacrifices the rest of the animal was taken home by the sacrificer, to be used for a meal or sent as a present to friends. This was, of course, impossible in the case of "holocausts," in which the victim was burnt whole on the altar. In the Roman ritual, hides and skins were always the property of the temple.37 In the above tariff two prices are charged: a smaller one for ordinary sacrifices, when only the intestines were burnt, and the rest of the flesh was taken home by the sacrificer; a larger one for "holocausts," which required a much longer use of the altar, spit, gridiron, and other sacrificial instruments. Four asses are charged for each crown or wreath of flowers, half that amount for hot water.

The site of a sanctuary can be determined not only from its actual ruins, but, in many cases, from the contents of its favissæ, or vaults, which are sometimes collected in a group, sometimes spread over a considerable space of ground. The origin of these deposits of terra-cotta or bronze votive objects is as follows:—

Each leading sanctuary or place of pilgrimage was furnished with one or more rooms for the exhibition and safe-keeping of ex-votos. The walls of these rooms were studded with nails on which ex-voto heads and figures were hung in rows by means of a hole on the back. There were also horizontal spaces, little steps like those of a lararium, or shelves, on which were placed those objects that could stand upright. When both surfaces were filled, and no room was left for the daily influx of votive offerings, the priests removed the rubbish of the collection, that is, the terra-cottas, and buried them either in the vaults (favissæ) of the temple, or in trenches dug for the purpose within or near the sacred enclosure.

During these last years I have been present at the discovery of five deposits of ex-votos, each marking the site of a place of pilgrimage. The first was found in March, 1876, on the site of a temple of Hercules, outside the Porta S. Lorenzo; the second in the spring of 1885, on the site of the Temple of Diana Nemorensis; the third in 1886, near the Island of Æsculapius (now of S. Bartolomeo); the fourth in 1887, near the shrine of Minerva Medica; the last in 1889, on the site of the Temple of Juno at Veii.

The existence of a temple of Hercules, outside the Porta S. Lorenzo, within the enclosure of the modern cemetery, was first made known in 1862, in consequence of the discovery of an altar raised to him by Marcus Minucius, the "master of the horse" or lieutenant-general of Q. Fabius Maximus (217 b. c.). This altar is now exhibited in the Capitoline Museum.38 Fourteen years later, in 1876, the favissæ of the temple were found in the section of the cemetery called the Pincio. There were about two hundred pieces of terra-cotta, vases of Etruscan and Italo-Greek manufacture; several statuettes of bronze, and pieces of æs rude, and æs grave librale, one of them from the town of Luceria. This deposit seems to have been buried at the beginning of the sixth century of Rome.

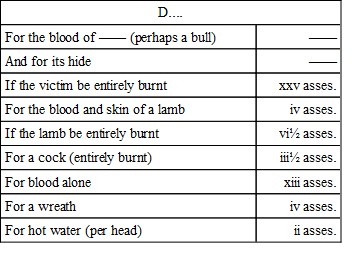

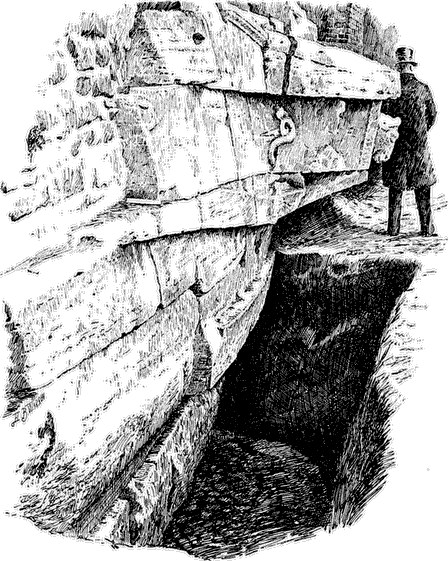

Nemi and the site of the Temple of Diana.

A Platform of the Temple of Diana. B Village of Nemi and Castle of the Orsinis.

Portrait Bust of Person cured at Nemi.

The excavation of the temple of Diana Nemorensis was undertaken in 1885, by Sir John Savile Lumley, now Lord Savile of Rufford, the English ambassador at Rome, with the kind consent of the Italian government. It seems that this Artemisium Nemorense was not only a place of worship and devotion, but also a hydro-therapeutic establishment. The waters employed for the cure were those which spring from the lava rocks at Nemi, and which, until a few years ago, fell in graceful cascades into the lake, at a place called "Le Mole." They now supply the city of Albano, which has long suffered from water-famine. I can vouch for their therapeutic efficiency from personal experience; in fact I could honestly put up my votive offering to the long-forgotten goddess, having recovered health and strength by following the old cure. Diana, however, was chiefly worshipped in this place as Diana Lucina. I need not enter into particulars on this subject. The ex-votos collected in large quantity by Lord Savile, representing young mothers nursing their first-born, and other offerings of the same nature, testify to the skill of the priests. Perhaps they practised other branches of surgery, because, among the curiosities brought to light in 1885, are several figures with large openings on the front, through which the intestines are seen. Professor Tommasi-Crudeli, who has made a study of this class of curiosities, says that they cannot be considered as real anatomical models, because the work is too rough and primitive to enable us to distinguish one intestine from the other. The number of objects collected by Lord Savile may be estimated at three thousand.

The stern of the ship of the Island of the Tiber.

Characteristic objects of a like nature—breasts cut open and showing the anatomy—have been found in large numbers in and near the island of the Tiber, where the Temple of Æsculapius stood, at the stern of the marble ship. It seems that the street leading from the Campus Martius to the Pons Fabricius, and across it to the temple, was lined with shops and booths for the sale of ex-votos, as is the case now with the approaches to the sanctuaries of Einsiedeln, Lourdes, Mariahilf, and S. Jago. In the foundations of the new quays of the Tiber, above and below the bridge, the ex-votos have been found in regular strata along the line of the banks, whereas in the island itself they have come to light in much smaller quantities. As the votive objects deposited in this sanctuary, from the year 292 before Christ to the fall of the Empire, may be counted not by thousands, but by millions of specimens, I believe that the bed of the Tiber must have been used as a favissa.

Fragment of a Lamp inscribed with the name of Minerva.

The name of Minerva Medica is familiar to students and visitors of old Rome;39 but the monument which bears it, a nymphæum of the gardens of the Licinii, near the Porta Maggiore, has no connection whatever with the goddess of wisdom. Minerva Medica was the name of a street on the Esquiline, so called from a shrine which stood at the crossing, or near the crossing, with the Via Merulana, not far from the church of SS. Pietro e Marcellino. Its foundations and its deposit of ex-votos were discovered in 1887. The shape and nature of the offerings bear witness to numberless cases of recovery performed by the merciful goddess, the Athena Hygieia or Paionia of the Greeks. There is a fragment of a lamp inscribed with her name, which leaves no doubt as to the identity of the deposit. There is also a votive head, not cast from the mould, but modelled a stecco, which alludes to Minerva as a restorer of hair. The scalp is covered with thick hair in front and on the top, while the sides are bald, or showing only an incipient growth. It is evident, therefore, that the woman whose portrait-head we have found had lost her curls in the course of some malady, and having regained them through the intercession of Minerva, as she piously believed, offered her this curious token of gratitude. This, at least, is Visconti's opinion. Another testimonial of Minerva's efficiency in restoring hair has been found at Piacenza, a votive tablet put up MINERVÆ MEMORI by a lady named Tullia Superiana, RESTITUTIONE SIBI FACTA CAPILLORUM (for having restored her hair).

Votive Head.