полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

As regards the multitude of ex-votos, no other temple or deposit discovered in my time can be compared with the favissæ of the Temple of Juno at Veii. In Roman traditions this temple was regarded as the place where Camillus emerged from the cuniculus, or mine, on the day of the capture of the city. The story runs that Camillus, having carried his cuniculus under the Temple of Juno within the citadel, overheard the Etruscan aruspex declare to the king of Veii that victory would rest with him who completed the sacrifice. Upon this, the Roman soldiers burst through the floor, seized the entrails of the victims, and bore them to Camillus, who offered them to the goddess with his own hand, while his followers were gaining possession of the city. The account is certainly more or less fabricated; but, as Livy remarks, "it is not worth while to prove or disprove these things." We are content to know that within the citadel of Veii, the "Piazza d' Armi" of the present day, there was a temple of great veneration and antiquity, and that it was dedicated to Juno. Both points have been proved and illustrated by modern discoveries.

The Cliffs under the Citadel of Veii (now called Piazza d' Armi).

The ex-votos of the Latin sanctuaries were, as I have just remarked, buried in the favissæ; but at Veii, because of the danger and the difficulty of excavating them within the citadel, and in solid rock, the ex-votos were carted away and thrown from the edge of the cliff into the valley below. The place selected was the north side of the rocky ridge connecting the citadel with the city, which ridge towers one hundred and ninety-eight feet above the cañon of the Cremera. The mass of objects thrown over here in the course of centuries has produced a slope which reaches nearly to the top of the cliff. The reader will appreciate the importance of the deposit from the fact that the mine has been exploited ever since the time of Alexander VII. (1655-1667); and in the spring of 1889, when the most recent excavations were made, by the late empress Theresa of Brazil, the mass of terra-cottas brought to the surface was such that work had to be given up after a few days, because there was no more space in the farmhouse for the storage of the booty. Pietro Sante Bartoli left an account of the excavations made on the same spot by cardinal Chigi, during the pontificate of Alexander VII. Modern topographers do not seem to be aware of this fact; it is not mentioned by Dennis, or Gell, or Nibby, although it is the only evidence left of the discovery of the famous sanctuary. "Not far from the Isola Farnese a hill [the Piazza d' Armi], rises from the valley of the Cremera, on the plateau of which cardinal Chigi has discovered a beautiful temple with fluted columns of the Ionic order. The frieze is carved with trophies and panoplies of various kinds; the reliefs of the pediment represent the emperor Antoninus[?] sacrificing a ram and a sow, and although the panels lie scattered around the temple, and the figures are broken, apparently no important piece is missing. There is also an altar four feet high, with figures of Etruscan type, which was removed to the Palazzo Chigi [now Odescalchi]. The columns and marbles of the temple were bought by cardinal Falconieri to build and ornament a chapel in the church of S. Giovanni de' Fiorentini.... Not far from the temple a stratum of ex-votos has been found, so rich that the whole of Rome is now overrun with terra-cottas. Every part of the human body is represented,—heads, hands, feet, fingers, eyes, noses, mouths, tongues, entrails, lungs, symbols of fecundity, whole figures of men and women, horses, oxen, sheep, pigs,—in such quantities as to make several hundred cartloads. There were also bronze statuettes, sacred utensils, and mirror-cases, which were all stolen or destroyed. I have known of one workman breaking marvellous objects (cose insigni) into small fragments to melt them into handles for knives."

When the farms of Isola Farnese and Vaccareccia, in which the remains of Veii and of its extensive cemeteries are situated, were sold, a few years ago, by the empress of Brazil to the marchese Ferraioli, the parties concerned agreed that the right of excavating and the objects discovered should belong to her, for a limited number of years, up to 1891, I believe. The first campaign, opened January 2, 1889, and closed in June, must be considered as one of the most valuable contributions to the study of Etruscan civilization which have been supplied of late to students, either by chance or by design. Had the empress been able to carry out her plans for two or three years more, the whole city and necropolis would have been explored, surveyed, and illustrated, in the most strictly scientific manner. Political events and the death of this noble woman brought the enterprise to a close. To come back, however, to the bed of votive objects in terra-cotta and bronze, I was able to make a rough estimate of its dimensions, which are two hundred and fifty feet in length, fifty feet in width, and from three to four in depth; nearly forty-four thousand cubic feet. The objects collected in two weeks number four thousand; the fragments buried again as worthless, double that number. The heads of veiled goddesses alone amount to four hundred and forty-seven, of which three hundred and seventy are full-faced, the rest in profile. The vein contains fifty-two varieties of types; to Bartoli's list, we must add busts, masks, arms, breasts, wombs, spines, bowels, lungs, toes, figures cut open across the breast and showing the anatomy, figures approximately human, or male and female embryos ending like the trunk of a tree with stumps corresponding to the feet, figures of hermaphrodites, human torsos modelled purposely without heads, arms without hands, legs without feet, hands holding apples or jewel-caskets, figurines of mothers nursing twins, beautiful life-sized statues of draped women, with movable hands and feet, rats, wild boars, sucking pigs, cows, rams, apples and other fruits, and "marbles."

The first structures dedicated to the gods in Rome were called aræ, and had the shape of a cube of masonry, in the centre of a square platform. They were modelled, in a measure, on the pattern of the Pelasgic hierones, in which the territory of Tibur and Signia is especially abundant. The aræ best known in Roman history and topography are six in number, namely, the ara maxima Herculis; the Roma quadrata; the ara Aii Locutii; the ara Ditis et Proserpinæ; the ara pacis Augustæ; and the ara incendii Neroniani. The oldest of these were built of rough stones; those of later periods took the characteristic shape of the altar of Verminus, represented on page 52 of my "Ancient Rome," and of the altar raised to Vedjovis by the members of the Julian family, at Bovillæ, their birthplace, where it was found by the Colonnas in 1823. It is now in the villa of that family on the Quirinal.40 In imperial times the conventional shape was preserved, with the addition of two pulvini, or volutes, on the opposite edges of the cornice, as represented in the illustration on page 35 of "Ancient Rome" (a marble altar found at Ostia).

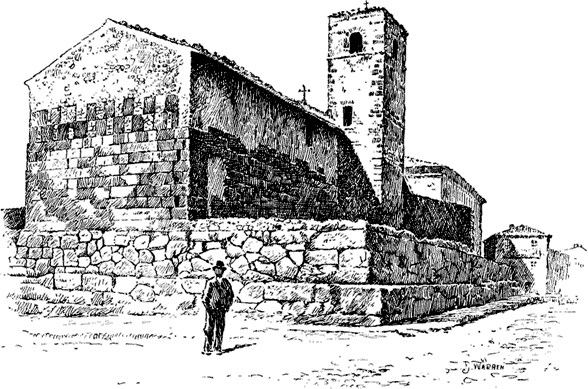

A Pelasgic hieron, or platform of altar, at Segni.

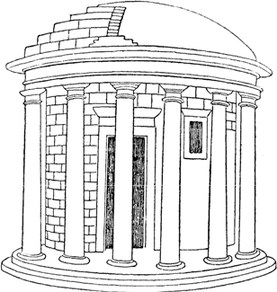

Round Temple of Hercules in the Forum Boarium.

The Ara Maxima Herculis. This altar, the oldest in Rome, was raised in memory of the visit of Hercules to our country. Tacitus and Pliny attribute its construction to Evander the Arcadian, forgetting that in prehistoric times the tract of land on which the altar stood, between the Forum Boarium and the Circus Maximus, was submerged by the waters of the Velabrum. It was at all events a very ancient structure, held in great veneration. Its rough shape and appearance were never changed, as shown by a precious—yet unpublished—sketch by Baldassarre Peruzzi which I found among his autographs in Florence. A round temple was built near the altar, in later times, of which we know two particulars: first, that it had a mysterious power of repulsion for dogs and flies;41 second, that it contained, among other works of art, a picture by the poet Pacuvius, next in antiquity and value to the one painted by Fabius Pictor, in the Temple of Health, in 303 b. c.42 The Temple of Hercules, the Ara Maxima, and the bronze statue of the hero-god were discovered, in a good state of preservation, during the pontificate of Sixtus IV., between the apse of S. Maria in Cosmedin (the Temple of Ceres), and the Circus Maximus. We have a description of the discovery by Pomponio Leto, Albertini, and Fra Giocondo da Verona; and excellent drawings by Baldassarre Peruzzi.43

Except the bronze statue, and a few votive inscriptions, which were removed to the Capitoline Museum, everything—temple, altar, and platform—was levelled to the ground by the illustrious Vandals of the Renaissance.

The Roma Quadrata. According to the ancient ritual, the founder of a city, after tracing the sulcus primigenius or furrow which marked its limits, buried the plough, the instruments of sacrifice, and other votive offerings, in a round hole, excavated in the centre of the marked space. The round hole was called mundus, and its location was indicated by a heap of stones, which in course of time took the shape of a square altar. The mundus of ancient Rome was located in the very heart of the Palatine, in front of the Temple of Apollo, and the altar upon it was named the Roma Quadrata. This name has been much discussed, and it has even been applied to the Palatine city itself, although it is an established fact that there is, strictly speaking, no connection between the two. The controversy has been resumed lately by Professor Luigi Pigorini in a paper still unpublished which was read at the sitting of the German Institute, December 17, 1890; and by Professor Otto Richter in his pamphlet Die älteste Wohnstätte des römischen Volks, Berlin, 1891.

In view of the ignorance of ancient writers on this subject, and the almost absurd definitions they give of the word, we had come to the conclusion that the altar had been removed or concealed by Augustus, when he built the Temple of Apollo and the Portico of the Danaids, in 28 b. c. A remarkable inscription discovered September 20, 1890 (to which I shall refer at length later), by mentioning the Roma Quadrata as existing a. d. 204, shows that our opinion was wrong, and that the old altar, the most venerable monument of Roman history, had survived the vicissitudes of time, and the transformation of the Palatine from the cradle of the city into the palace of the Cæsars.

In December, 1869, when the nuns of the Visitation were laying the foundations of a new wing of their convent on the area of the Temple of Apollo,44 I saw a line of square pilasters at the depth of forty-one feet below the pavement of the Portico of the Danaids, and in the centre of the line a heap of stones, either of tufa or peperino, roughly squared. It is more than probable that, in 1869, I did not think of the Roma Quadrata, and of its connection with those remains, so deeply buried in the heart of the hill; but I am sure that a careful investigation of that sacred spot would lead to very important results.

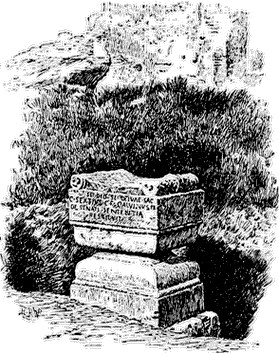

Ara of Aius Locutius on the Palatine.

The Ara of Aius Locutius. In 1820, while excavations were proceeding near the western corner of the Palatine (at the spot marked No. 7, on the plan, page 106, of "Ancient Rome"), an altar was discovered, of archaic type, inscribed with the following dedication: "Sacred to a Divinity, whether male or female. Caius Sextius Calvinus, son of Caius, praetor, has restored this altar by decree of the Senate." Nibby and Mommsen believe Calvinus to be the magistrate mentioned twice by Cicero as a candidate against Glaucias in the contest for the praetorship of 125 b. c. They also identify the altar as (a restoration of) the one raised behind the Temple of Vesta, in the "lower New Street," in memory of the mysterious voice announcing the invasion of the Gauls, in the stillness of the night, and warning the citizens to strengthen the walls of their city. The voice was attributed to a local Genius, whom the people named Aius Loquens or Locutius. As a rule, the priests refrained from mentioning in public prayers the name and sex of new and slightly known divinities, especially of local Genii, to which they objected for two reasons: first, because there was danger of vitiating the ceremony by a false invocation; secondly, because it was prudent not to reveal the true name of these tutelary gods to the enemy of the commonwealth, lest in case of war or siege he could force them to abandon the defence of that special place, by mysterious and violent rites. The formula si deus si dea, "whether god or goddess," is a consequence of this superstition; its use is not uncommon on ancient altars; Servius describes a shield dedicated on the Capitol to the Genius of Rome, with the inscription: GENIO URBIS ROMÆ SIVE MAS SIVE FEMINA, "to the tutelary Genius of the city of Rome, whether masculine or feminine." The Palatine altar, of which I give an illustration, cannot fail to impress the student, on account of its connection with one of the leading events in history, the capture and burning of Rome by the Gauls, 390 b. c.

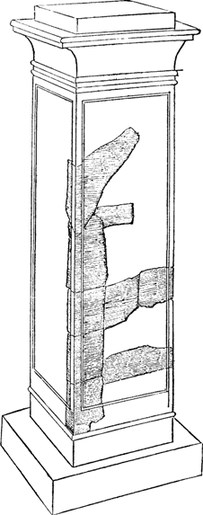

Pillar commemorating the Ludi Sæculares.

The Ara Ditis et Proserpinæ. On the 20th of September, 1890, the workmen employed in the construction of the main sewer on the left bank of the Tiber, between the Ponte S. Angelo and the church of S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini, found a mediæval wall, built of materials collected at random from the neighboring ruins. Among them were fragments of one or more inscriptions which described the celebrations of the Ludi Sæculares under the Empire. By the end of the day, seventeen pieces had been recovered, seven of which belonged to the records of the games celebrated under Augustus, in the year 17 b. c., the others to those celebrated under Septimius Severus and Caracalla, in the year 204 a. d. Later researches led to the discovery of ninety-six other fragments, making a total of one hundred and thirteen, of which eight are of the time of Augustus, two of the time of Domitian, and the rest date from Severus.

The fragments of the year 17 b. c., fitted together, make a block three metres high, containing one hundred and sixty-eight minutely inscribed lines. This monument, now exhibited in the Baths of Diocletian, was in the form of a square pillar enclosed by a projecting frame, with base and capital of the Tuscan order, and it measured, when entire, four metres in height. I believe that there is no inscription among the thirty thousand collected in volume vi. of the "Corpus" which makes a more profound impression on the mind, or appeals more to the imagination than this official report of a state ceremony which took place over nineteen hundred years ago, and was attended by the most illustrious men of the age.

The origin of the sæcular games seems to be this: In the early days of Rome the northwest section of the Campus Martius, bordering on the Tiber, was conspicuous for traces of volcanic activity. There was a pool here called Tarentum or Terentum, fed by hot sulphur springs, the efficiency of which is attested by the cure of Volesus, the Sabine, and his family, described by Valerius Maximus. Heavy vapors hung over the springs, and tongues of flame were seen issuing from the cracks of the earth. The locality became known by the name of the fiery field (campus ignifer), and its relationship with the infernal realms was soon an established fact in folk-lore. An altar to the infernal gods was erected on the borders of the pool, and games were held periodically in honor of Dis and Proserpina, the victims being a black bull and a black cow. Tradition attributed this arrangement of time and ceremony to Volesus himself, who, grateful for the recovery of his three children, offered sacrifices to Dis and Proserpina, spread lectisternia, or reclining couches, for the gods, with tables and viands before them, and celebrated games for three nights, one for each child which had been restored to health. In the republican epoch they were called Ludi Tarentini, from the name of the pool, and were celebrated for the purpose of averting from the state the recurrence of some great calamity by which it had been afflicted. These calamities being contingencies which no man could foresee, it is evident that the celebration of the Ludi Tarentini was in no way connected with definite cycles of time, such as the sæculum.

Not long after Augustus had assumed the supreme power, the Quindecemviri sacris faciundis (a college of priests to whom the direction of these games had been intrusted from time immemorial) announced that it was the will of the gods that the Ludi Sæculares should be performed, and misrepresenting and distorting events and dates, tried to prove that the festival had been held regularly at intervals of 110 years, which was supposed to be the length of a sæculum. The games of which the Quindecemviri made this assertion were the Tarentini, instituted for quite a different purpose, but their suggestion was too pleasing to Augustus and the people to be despised. Setting aside all disputes about chronology and tradition, the celebration was appointed for the summer of the year 17 b. c.

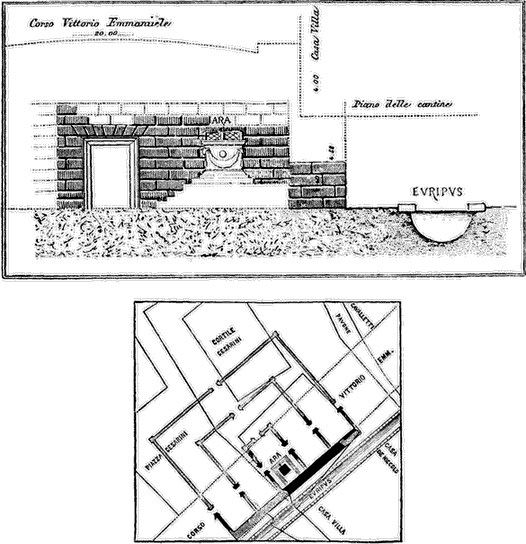

Plan and section of the Altar of Dis and Proserpina.

What was the exact location of the sulphur springs, the Tarentum, and the altar of the infernal gods? I have reason to regard the discovery of the Altar of Dis and Proserpina as the most satisfactory I have made, especially because I made it, if I may so express myself, when away from Rome on a long leave of absence. It took place in the winter of 1886-87, during my visit to America. At that time the work of opening and draining the Corso Vittorio Emanuele had just reached a place which was considered terra incognita by the topographers, and indicated by a blank spot in the archæological maps of the city. I mean the district between the Vallicella (la Chiesa Nuova, the Palazzo Cesarini, etc.) and the banks of the Tiber near S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini. The reports spoke vaguely about the discovery of five or six parallel walls, built of blocks of peperino, of marble steps in the centre of this singular monument, of gates with marble posts and architraves, leading to the spaces between the six parallel walls, and finally, of a column with foliage carved upon its surface. On my return to Rome, in the spring of 1887, every trace of the monument had disappeared under the embankment of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele. I questioned foremen and workmen, I consulted the notebooks of the contractors, every day I visited the excavations which were still in progress, on each side of the Corso, for building the Cavalletti and Bassi palaces, and lastly, I examined the "column with foliage carved upon its surface," which in the mean time had been removed to the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitol. This marble fragment, the only one saved from the excavations, gave me the clue to the mystery. It was not a column, it was a pulvinus, or volute, of a colossal marble altar, worthy of being compared, in size and perfection of work, with the Altar of Peace discovered under the Palazzo Fiano, with that of the Antonines discovered under the Monte Citorio, and with other such monumental structures. There was then no hesitation in determining the nature of the discoveries made in the Corso Vittorio Emanuele; an altar had been found there, and this altar must have been the one sacred to Dis and Proserpina, as no other is mentioned in history in the northwest section of the Campus Martius.

The drawings which illustrate my account of the discovery45 prove that the altar rose from a platform twelve feet square, approached on all sides by three or four marble steps, that platform and altar were enclosed by three lines of wall at an interval of thirty-six feet from one another, and that on the east side of the square ran a euripus, or channel, eleven feet wide, and four feet deep, lined with stone blocks, the incline of which towards the Tiber is about 1:100. This last detail proves that when the rough altar of Volesus Sabinus was succeeded by the later noble structure, the pool was drained, and its feeding springs were led into the euripus, so that the patients seeking a cure for their ailments could bathe in or drink the miracle-working waters with greater ease. No attention whatever was paid to the discovery at the time it took place. Instead of reaching the ancient level, the excavation for the main sewer of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele was stopped at the wrong place, within three feet of the pavement; consequently whatever fragments of the altar, of inscriptions, or of works of art, were lying on the marble floor will lie there forever, as the building of the palaces on either side of the Corso, and the construction of the Corso itself, with its costly sewers, sidewalks, etc., have made further research impossible, at least with our present means.

Concerning the celebration which took place around this altar in the year 17 b. c., we already possessed ample information from such materials as the oracle of the Sibyl, referred to by Zosimus, the Carmen Sæculare of Horace, and the legends and designs on the medals struck for the occasion; but the official report, discovered September 20, 1890, produces an altogether different impression; it enables us actually to take part in the pageant, to follow with rapture Horace as he leads a chorus of fifty-four young men and girls of patrician birth, singing the hymn which he composed for the occasion.46

There is such a tone of simplicity and common-sense, such a display of method and mutual respect between Augustus, the Senate, and the Quindecemviri, in the official transactions which preceded, attended and followed the celebration, in the resolutions passed by the several bodies, in the proclamations addressed to the people, and in the arrangements for the festivities, which a mass of a million or more spectators was expected to attend, that a lesson in civic dignity could be learned from this report by modern governments and corporations.

The official report begins, or rather began (the first lines are missing), with the request presented by the Quindecemviri to the Senate to take their proposal into consideration, and grant the necessary funds, followed by a decree of the Senate accepting the proposal and inviting Augustus to take the direction of the festivities. The request was addressed to the Senate on February 17, by Marcus Agrippa, president of the Quindecemviri, standing before the seat of the consuls. What a scene to witness! We can picture to ourselves the two consuls, Gaius Furnius and Junius Silanus, clad in their official robes, listening to the speech of the great statesman, who is supported by twenty colleagues, all ex-consuls, and chosen among the noblest, richest, and most gallant patricians of the age. The Senate agrees that the preparations for the festival, the building of the temporary stages, hippodromes, tribunes, and scaffoldings shall be executed by the contractors (redemptores), and that the treasury officials shall provide the funds.

Lines 1-23 contain a letter from Augustus to the Quindecemviri detailing the programme of the ceremonies, the number and quality of persons who shall take part in it, the dates and hours, and the number and character of the victims. Two clauses of the imperial manifesto are especially noteworthy. First, that during the three days, June 1-3, the courthouses shall be closed, and justice shall not be administered. Second, that ladies who are wearing mourning shall lay aside that sign of grief for this occasion. The date of the manifesto is March 24.