полная версия

полная версияA Manual of the Operations of Surgery

Fig. xxxiv. 151

But it may now be said, If this be the case, we are very much limited in the size of the incision we may make into the bladder. We cannot remove a large stone, for the prostate ought not to be larger than a good-sized chestnut, and any cut we might make through a chestnut without cutting out of its side must be very small. Very true; but fortunately the sheath of the prostate, unlike the rind of the chestnut, is very freely dilatable, and will allow the passage of a very considerable stone.

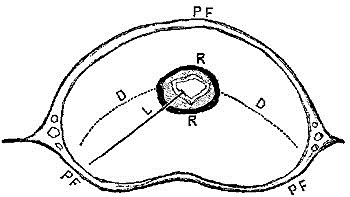

Again, an inquirer might ask, If it is so dilatable, why should we run the risk of cutting the prostate at all? Why should we not introduce instruments gradually increasing in size into the membranous portion of the urethra, and thus dilate prostate and neck of bladder? For this reason, that the urethral canal passing through the prostate is itself lined immediately outside of the mucous membrane by a firm membranous sheath (Fig. xxxiv. rr), which resists dilatation to the utmost. Experience tells us that any attempts to dilate or even forcibly to tear this ring of fibrous texture are both ineffectual and dangerous, while a clean cut into it and through it into the substance of the prostate is at once effectual and comparatively safe.

In a word, we can describe the relation of the prostate to the operation of lithotomy somewhat in this manner:—Its fibrous sheath surrounding the urethra must be cut freely. The gland substance may be cut and freely dilated by the finger. Its fibrous envelope must, as far as possible, be preserved intact, but this interferes the less with the operation, as it is comparatively freely dilatable.

The firm lining of the urethra, which must be cut, is specially strong at its base, forming a tough resisting band just at the aperture of the bladder, which, unfortunately, is often so high up in the pelvis in tall patients, or in cases in which the prostate is much enlarged, as to be almost out of reach of the finger, and so far up the staff as perhaps to escape division. You will be warned of such an occurrence by the urine in the bladder failing to make its appearance; and if any attempt be made to dilate the opening and introduce the forceps without further incision of the base of the prostate, the result will very likely be fatal, generally from pyæmic symptoms depending on a suppurative inflammation of the prostatic plexus of veins (Fig. xxxiv.). In fact, upon a recognition of this fact is founded the aphorism, "that cases in which the forceps have been introduced before the bladder fairly begins to empty its contents are generally fatal."

Fig. xxxv. 152

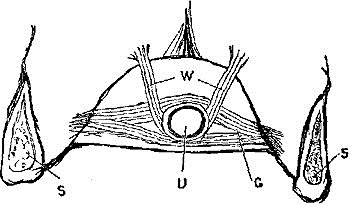

We have thus traced the necessary guiding principles as to our incisions from the bladder outwards through the prostatic portion of the urethra. We have next to discover what sort of an opening is necessary in the membranous portion of the urethra consistent with the fulfilment of the same conditions, namely, freedom of escape for the urine, and room enough to remove the stone. Both of these are gained at once by a free incision of the membranous portion, dividing especially those anterior fibres of the great sphincter muscle of the pelvis, the levator ani, which embrace the membranous portion, under the special names of compressor (Fig. xxv.) and levator urethræ (Guthrie's and Wilson's muscles).

The principles which guide the position and size of the preliminary incisions which enable the urethra to be opened are very simple:—(1.) The wound in the perineum should be large enough to give free access to the urethra, and easy egress to the stone; (2.) It should be conical, with its base outwards, so as to favour escape of urine and prevent infiltration; (3.) It should not wound any important organ or vessel; that is, it must avoid the rectum, the corpus spongiosum, especially the bulb, if possible, the artery of the bulb, and in every case should leave the pudic artery intact.

So far for broad general principles, which must guide all methods of successful lithotomy.

The Lateral Operation.—Operation of Cheselden.—(1.) Instruments required.—A staff with a broad substantial handle, and a longer curve than the ordinary catheter requires, furnished with a very deep and wide groove, which occupies the space midway between its convexity and its left side. The one used should invariably be large enough to dilate fully the urethra.

A knife, with its blade three or four inches in length, but sharp only for an inch and a half from its point, its back straight up to within a sixth of an inch of its point, and there deflected at an angle to the point, which again curves to the edge. The angle from the back to the point permits the knife to run more freely along the groove in the staff.

A probe-pointed straight knife with a narrow blade may occasionally be useful in enlarging the incision in the prostate, when this is required by the size of the stone.

Forceps of various sizes and shapes, some with the blades curved at an angle to reach stones lying behind an enlarged prostate, all with broad blades as thin as is consistent with perfect inflexibility, the blades hollowed and roughened in the inside, but without the projecting teeth sometimes recommended, which are dangerous from being apt to break the stone.

A scoop to remove fragments or small stones, sometimes useful with the aid of the forefinger in lifting out a large one.

A flexible tube of at least half an inch calibre, and about six inches long, rounded off and fenestrated above, fitted at its outer end with a ring and two eyelet-holes for the tapes, with which it is tied into the bladder.

Prior to the operation the patient's health should be attended to, the stomach and bowels regulated, and any disorder of the kidneys or bladder as far as possible alleviated. If his health has been good and habits active, three or four days' confinement to his room on low diet, with a full purge the evening before the operation, is all the preparatory treatment that is necessary.

It is of the utmost importance for the safety of the operation and the patient's comfort after it, that the rectum be completely unloaded before the operation, and the bowels so far emptied as to permit three or four days after the operation to elapse without any movement of the bowels being necessary. If there is any doubt as to the effect of the laxative, a large stimulant enema should be administered on the morning of the operation.

Position.—Much depends on the proper tying up of the patient. He should be placed with his breech projecting over the edge of a narrow table, with head slightly raised on a pillow, but the shoulders low. The hands are then to be secured each to its corresponding foot, by a strong bandage passing round wrist and instep, or by suitable leather anklets, the knees should be wide apart, and on exactly the same level, so that the pelvis may be quite straight. An assistant should be placed to take charge of each leg.

The staff is next introduced and the stone felt; if there is little water in the bladder a few ounces may be injected, but this is rarely necessary, for the patient should be ordered to retain as much water as possible, and when he cannot retain it, injection of water may do harm, and will probably not be retained, but at once come away along the groove in the staff. The staff is then committed to a special assistant, who must be thoroughly up to his duty, and attend to the staff alone.

Some surgeons direct the assistant to make the convexity of the staff bulge in the perineum, to enable the groove to be struck more easily. It will be, however, safer both for the rectum and the bulb, if the staff be hooked firmly up against the symphysis pubis, as advised by Liston. The same assistant can also keep the scrotum up out of the way.

If the perineum has not been previously shaved, this is now done.

The operator sits down on a low stool in front of the patient's breech, his instruments being ready to his hand, and then steadying the skin of the perineum with the fingers of his left hand, enters the point of the knife in the raphe of the perineum, midway between the anus and scrotum (one inch in front of anus—Cheselden, Crichton; one and a quarter—Gross, Skey, and Brodie; one and three-quarters—Fergusson; one inch behind the scrotum—Liston), and carries the incision obliquely downwards and outwards, in a line midway between the anus and tuberosity of the ischium. The length of the incision must vary with the size of the perineum, and the supposed size of the stone, but there is less risk in its being too large, so long as the rectum is safe, than in its being too small. Its depth should be greatest at its upper angle, where it has to divide the parts to the depth of the transverse muscle of the perineum, and least at its lower angle, where a deep incision is not required, and would be almost sure to wound the rectum.

The forefinger of the left hand is now to be deeply inserted into the wound, and any remaining fibres of the levator ani in front are to be divided, the edge of the knife being directed from above downwards. The left forefinger being still used to push its way through the cellular tissue, the groove in the staff is now felt in the membranous portion of the urethra covered by the deep fascia of the perineum. Now comes the deeper part of the incision. Guided by the finger-nail of the left hand, the surgeon introduces the point of the knife into the groove of the staff. He then takes hold of the staff for a moment to feel that it is held up properly against the pubis, and in the middle line, and also that the knife is fairly in the groove. Giving the staff back again to the assistant, and keeping the rectum well out of the way by the left hand, he now steadily directs the knife along the groove of the staff till the bladder is fairly entered, and the ring at the base of the prostate completely divided. When this is the case a gush of urine takes place, following the withdrawal of the knife.

When making the deep incision, and in the groove of the staff, the blade of the knife should lie neither vertical nor horizontal, but midway between the two, so as to make the section of the left lobe of the prostate in its longest diameter, that is, in a direction downwards and backwards (Fig. xxxiv. L).

The knife is now withdrawn, and the left forefinger inserted. In most cases it will be long enough to reach the bladder and touch the stone, and may then be freely used by gradual pressure to dilate the wound; this may be done very freely when necessary for a large stone, if only the ring of fibrous tissue surrounding the urethra be first cut and the bladder fairly entered. Whenever the stone is felt by the finger, the assistant may withdraw the staff.

When the operator has thus felt the stone and sufficiently dilated the wound, the next step is to introduce the forceps; this should be done under the guidance of the finger, and with the blades closed. When the stone is felt the blades should be opened very widely, slightly withdrawn, and then pushed in again, the lower one, if possible, being insinuated under the stone. The blades must be made fairly to grasp and contain the stone in their hollow, for if they only nibble at the end of an oval stone, extraction is impossible. Extraction should then be performed slowly, with alternate wrigglings of the forceps from side to side, so as gradually to dilate, not to tear, the prostate, and the operator must remember to pull in the axis of the pelvis, not against the os pubis or the promontory of the sacrum.

If there is much resistance, it may possibly be caused by the stone having been caught in its longer axis, and this may be remedied by careful manipulation by means of the finger and forceps. If the stone is still too large to be extracted without greater force than is warrantable, there are still various expedients (see infra, pp. 265, 270).

In most cases, however, the stone is removed rapidly enough by the single incision. The finger, or a sound, must then be introduced to feel if any more stones are present. The closed forceps make a very effectual instrument for this purpose. Much information may be gained from the appearance of the first stone, the presence or absence of facets. Its smoothness or roughness enables us to form a pretty certain opinion; yet the bladder should always be carefully searched; and if the stone has been friable or broken in extraction, should be washed out by a current of water. Where the calculi are very numerous, or where many fragments have separated, the scoop will be found useful, both for detecting and removing them. All the stones being extracted, there is in most cases little or no bleeding (see infra, Hæmorrhage). The tube already described may now be inserted and tied into the bladder. It may be retained for forty-eight or seventy-two hours, according to circumstances. Care must be taken lest it be closed up by coagula during the first hour or two after the operation. In children the tube is not necessary, and from their restlessness might possibly do harm, but in adults (though neglected by some surgeons) experience shows it is a valuable adjunct in the after-treatment.

Having thus traced the course of an ordinary uncomplicated case of lithotomy by the lateral operation, a brief notice is suitable of some of the obstacles and difficulties, some of the dangers and bad results which may be met with, and the best methods of overcoming them.

1. Large size of the stone, as an obstacle to extraction. When, either from the enormous size of the stone, generally to be made out before the operation, or from some congenital or acquired deformity of the pelvis, it is obvious beforehand that the calculus cannot pass through the bony pelvis entire, a choice of two courses remains, either—

(1.) The high or supra-pubic operation (q.v. infra); or (2.) Crushing of the calculus in the bladder, and removal piecemeal. Instruments of great strength have been devised for this latter operation. The risk to the bladder is very great, and fragments are apt to be left behind; these are sure to form nuclei of new calculi.

2. Peculiarities in the position or relations of the stone in the bladder:—

(1.) It may lie in a sort of pouch behind the prostate, and thus be out of the reach of the forceps. This may be remedied by the use of curved forceps, or, better still, by the finger in the rectum to tilt up the stone into the bladder.

(2.) It may lie above the pubis in the anterior wall of the bladder. Pressure on the hypogastrium, or the use of a strong probe as a hook, will generally suffice to dislodge it.

(3.) The stone may be encysted. This is extremely rare, and, as Fergusson says, we hear more of these from bunglers who have operated only several times, than from those who have had large experience.

3. An enlarged prostate is at once a source of difficulty and of some danger.

The distance of the bladder from the surface may be so very much increased by enlargement of the prostate as to render even the longest forefinger too short to reach the stone or even the bladder. This renders the introduction of the forceps more difficult and uncertain, the dilatation more prolonged, and the extraction more dangerous. If very large, the groove of the staff may not reach the bladder, and thus the deep incision may fail of cutting the ring at the base of the gland, and the urine may thus not escape, and all the dangers of laceration of the ring may result. Such cases may be well managed by the insertion of a straight deeply grooved staff into the insufficient incision, and fairly into the bladder, and on this, pushing a cutting gorget through the uncut portion of the gland. This insures a sufficient yet not dangerous incision, which we cannot so safely perform with the knife, as the parts are so far beyond the reach of the guiding forefinger.

Under the head of risks after lithotomy we may class the following:—

1. Sinking, or shock. In the very aged or very young, or after a very prolonged or painful operation, shock may now and then kill the patient within a few hours. Since the days of chloroform this result is extremely rare.

2. Hæmorrhage seems to be a very infrequent risk. The transverse perineal artery, which is always cut in the operation, is small, and rarely bleeds much. If the bulb is wounded, as no doubt frequently occurs, the flow from it can easily be checked. The pudic is so well protected from any ordinary incision as to be practically safe; and if wounded by some frightfully extensive incision, it can be compressed against the tuberosity of the ischium.

There is an abnormal distribution of the dorsal artery of the penis, in which, rising higher up than it ought, and coursing along the neck of the bladder, and the lateral lobe of the prostate, it may be divided. This may give trouble, and even result in fatal hæmorrhage. Fortunately it is rare. The author has met with one case in a boy of eleven, in whom a very severe hæmorrhage was not to be explained. The patient recovered without another bad symptom.

Again, a general oozing may often appear a few hours after the operation, when the patient is warm in bed, apparently from the substance of the prostate. If raising the breech and the application of cold fail to arrest it, it may be necessary to plug the wound. This is done by stuffing it with long strips of lint round the tube. Great care must be then taken lest the tube become occluded.

3. Infiltration of urine may occur as a result of a too free incision of the vesical fascia (in adults), and still more frequently of a too small external wound.

Here it should be noticed that in children it is fortunately of very little consequence to preserve the integrity of the prostatic sheath of vesical fascia. In them the prostate is so exceedingly small and undeveloped, that even the forefinger could not be introduced into the bladder without a complete section of the prostate. Probably from the blander nature of their urine, and the greater vitality of their tissues, this is of less consequence, as it is rarely found that any bad effects result from this section.

Among other risks we find peritonitis, inflammation of neck of bladder, inflammation of prostatic plexus of veins, resulting in pyæmia, suppression of urine, and other kidney complications. For the symptoms and treatment of these there is no place in a mere manual of surgical operations.

Wound of rectum and recto-vesical fistula.—Such wounds were not uncommon, and in many cases unavoidable, before the days of chloroform, from the struggles of the patient; now they are comparatively rare, and should be still rarer. They probably occur in more cases than the surgeon is aware of, and heal up without his knowledge; we may arrive at this conclusion from the fact that small wounds are found in post-mortem examinations of cases in which no such complication has been thought of.

They occasionally heal without giving any trouble, but, at other times, as the external wound contracts, a communication forms between rectum and the urethra, in which the contents are apt to be interchanged in a most disagreeable manner, flatus passing per urethram, and urine per rectum.

When it is evidently not going to heal spontaneously, the septum between the external orifice of the wound and the communication with the gut should be laid open, as in the operation for fistula in ano.

There are certain modifications and varieties in the method of operating for stone through the perineum, which deserve at least a brief notice:—

1. The bilateral operation.—Though he was not the inventor, Dupuytren's name is justly associated with this operation. The principle of it is to divide both sides of the prostate equally, so as to give more room for extraction of a large stone, without the necessity of much laceration, or the risk of cutting through the prostatic sheath of fascia.

The operation.—A semilunar incision is made transversely across the perineum, extending from a point midway between the right tuber ischii and the anus, upwards, crossing the raphe nearly an inch above the anus, and then curving downwards to a corresponding point on the opposite side. The skin, superficial fascia, and a few of the anterior fibres of the external sphincter, are thus divided, and the groove of the staff sought by the forefinger. The membranous portion of the urethra is then laid open in the middle line, and the beak of a double lithotome caché securely lodged in the groove. It is then pushed into the bladder with its concavity upwards, and when fairly in it is turned round, its blades protruded to the required extent, and withdrawn with its concavity downwards, thus dividing both lobes of the prostate in a direction downwards and outwards (Fig. xxiv. D D). The operation is finished in the usual manner. Though it is a comparatively easy operation, and theoretically may be proved to have many advantages, experience has shown that the results are not so favourable as those of the ordinary lateral operation.

2. Buchanan's medio-lateral operation on a rectangular staff.—The staff is bent at a right angle three inches from the end, and deeply grooved on its left side. This is introduced into the urethra so that the angle projects the membranous portion of the urethra close to the apex of the prostate and the terminal straight portion enters the bladder parallel to the rectum. The angle projects in the perineum, so that the operator with his left forefinger in the rectum is enabled, by a stab with a long straight bistoury (held horizontally and with the cutting edge to the left side), at once to enter the groove, and, by following the groove, the bladder. Whenever the escape of urine shows that the bladder is fairly reached, the knife is withdrawn so as to make a lateral section of the prostate, and then, with the finger still in the rectum, to make an incision in the ischio-rectal fossa, of sufficient size to allow the stone to be easily withdrawn.

The inventor claims for this method that it is easier, that there is less risk of hæmorrhage, wound of the rectum, and infiltration of urine.

3. Allarton's operation of median lithotomy suits admirably for stones known to be small, but is quite unsuitable for large ones. Probably in most cases it should be superseded by lithotrity.

Operation.—A large curved staff with a central groove is to be held firmly hooked up against the symphysis pubis, and then steadied by the left forefinger in the rectum. The operator pierces the raphe of the perineum with a long straight bistoury about half an inch above the verge of the anus, enters the groove of the staff, and cuts inwards, almost, but not quite, into the bladder. In withdrawing the knife the wound in the urethra is enlarged upwards towards the scrotum. A ball-pointed probe is then passed on the staff into the bladder, the staff is withdrawn, and the finger, guided by the probe, is used to dilate the neck of the bladder, to an extent sufficient for the removal of the stone by a small pair of forceps.

In this operation the prostate is hardly incised at all. The results are not better than those of the lateral operation.

2. Lithotomy above the Pubes, or the High Operation.—In cases where, from the known size of the stone, or from the deformity of the bones of the pelvis, it is impossible that the stone can be extracted entire in the usual manner; in cases where the prostate is very much enlarged, or where there is any real or supposed likelihood of inflammation of the neck of the bladder, the supra-pubic operation may be warrantable. Its performance is easy, it does not involve any wound of the peritoneum if properly performed, and there is no risk of hæmorrhage. There are certainly great risks attending it of peritonitis and urinary infiltration.

In more than one case this operation has been attended by wound of peritoneum and subsequent escape of intestines through the wound, even when dressed antiseptically and performed under spray.

Operation.—The patient lies on his back, with his head and shoulders slightly raised, so as to relax the abdominal muscles, and his legs hanging down over the edge of the table. If his bladder can bear it, it should be fully distended, either by voluntary retention of the urine, or by injection with tepid water. A vertical incision is then made in the middle line, separating the recti muscles from below upwards, care being taken to push the peritoneum well out of the way, which is easily done by the finger in the loose cellular tissue of the part. The anterior wall of the bladder is then exposed, uncovered by peritoneum; it must be opened with great care, also in the middle line, while the wound in the parietes is held aside by retractors. The wall of the bladder should be transfixed by a curved needle, and thus held in position before it is opened. The stone is then removed by a pair of straight forceps, generally with great ease. Attempts used to be made to leave a catheter or canula in the bladder wound to prevent infiltration. Probably the safest method now will be to close the bladder wound at once by metallic stitches, and stitching the abdominal wound carefully with deeply entered wires, to leave the patient on his back. When compared with the lateral operations the statistics of the supra-pubic operation are discouraging, the mortality being one in three and a half to one in four. But in cases where the stone is known to be very large and of firm consistence, the risks are probably less from this method than from lateral lithotomy, followed by efforts to crush the stone through the wound prior to its removal.