полная версия

полная версияA Manual of the Operations of Surgery

If the rupture is large, a single linear, or a T-shaped incision, exposing the base of the tumour, will be sufficient to allow the requisite dilatation of the opening to be made. It is not at all necessary in every case to open the sac of the peritoneum. If required, it must be done with great caution, as the sac is generally very thin. In cases where the hernia is chiefly omental, the sac should be opened, lest a knuckle of bowel be inclosed and strangulated in the omentum.

Obturator Hernia is an extremely rare lesion, and a large proportion of the recorded cases were discovered only after death. When diagnosed during life and strangulated, some have been reduced by taxis, and only a very few cases have been operated on, some with success. It is not likely that a diagnosis could be made, except in very emaciated patients, in whom pain at the obturator foramen was a prominent symptom, and in whom it could be ascertained positively that the crural ring was empty. An incision over the tumour, sufficient to allow the pectineus muscle to be exposed and divided, is necessary. The hernia may then be reduced without opening the sac, if recent; if of long standing, the sac must be opened. One case is recorded by Dr. Lorinzer, in which, after strangulation for eleven days, he opened the sac and found the bowel gangrenous. The patient had a fæcal fistula; but survived the operation for eleven months. Nuttel, Obrè, and Bransby Cooper have each diagnosed and treated such cases.147

Other forms of hernia are so rare, and the treatment of each case must necessarily vary so much in its circumstances, as not to require or admit of any detailed account of the operations requisite for their relief.

Operations for the Radical Cure of Hernia.—The inconveniences and discomfort caused by even the best-adjusted trusses or bandages, the unsatisfactory support they afford, and the risk of their slipping and allowing the hernia to escape, have given rise to many attempts to cure hernia by operation.

Even to enumerate these would be quite beyond the limits of the present volume; suffice it to classify a few of the most important of them according to the principle involved in each, and then give a very brief account of the method of operating which seems to be at once the most scientific, least dangerous, and most permanently useful.

The question at issue is briefly this. We have, in a hernia, the following condition:—The walls of a great cavity are at one or more points specially weak, the contained viscera have protruded, either by extension and stretching of a natural opening, or by the formation of a new breach in the walls, and, in protruding, they have brought with them as a covering a serous membrane, extremely extensible, highly sensitive to injury, and, when injured, certain to resent it by severe, spreading, and dangerous inflammation.

Do we desire to remedy this protrusion, we may act—

1. On the intestines themselves; but for all surgical purposes, they are out of our reach. We cannot do more than, by diminishing their contents, diminish their volume, and by position and rest reduce to the utmost their tendency to protrude. This includes the medical and prophylactic treatment of hernia, or rather of the tendency to hernia.

2. We may try what can be done with the sac which the intestines have pushed down before them. Can it be obliterated? If it can, perhaps the intestines may be retained in their cavity. Very many plans of dealing with the sac have been tried.

To cause obliteration of its cavity many methods have been proposed:—by ligature of it along with the spermatic cord, involving loss of the testicle, either by gradual separation, by sloughing, or by immediate removal;—by cutting into it, and then stitching it up;—by constricting it with wire, as in the punctum aureum; by pinching sac and coverings up, by passing needles under them as they emerge from the external ring, as Bonnet of Lyons did; by constricting sac alone with a double wire, by subcutaneous puncture, as Dr. Morton of Glasgow has done;—by severe pressure from the outside with a strong tight truss and a pad of wood, as proposed by Richter; by setons of threads or candlewicks, as proposed by Schuh of Vienna;—by injection of tincture of iodine or cantharides, as by Velpeau and Pancoast;—by the introduction into the sac of thin bladders of goldbeaters' skin, which were then filled with air, and were intended to excite inflammation, as in the radical cure of hydrocele; or by the still more severe method of Langenbeck, consisting in exposing the sac by a free incision at the superficial ring, separating it from the cord, and passing a ligature round the sac alone, leaving the ligatured portion in the scrotum either to become obliterated or to slough out. Schmucker of Berlin varied this, by cutting away the constricted portion below the ligature.

The objections to these methods are various: the more gentle are uncertain and inefficient; of the more severe, some involve mutilation, by the loss or removal of the testicle; others, as those of Langenbeck and Schmucker, are very dangerous and fatal, by the inflammation spreading to the peritoneal cavity (20 to 30 per cent. died); while all of these methods afford at best only temporary relief. And this is only what might have been expected, for the sac was only a result of the protrusion, not a cause; and so long as the weakness and insufficiency of the parietes of the abdomen remain, so long will the extensible loosely-attached peritoneum continue to furnish new sacs for visceral protrusions.

3. We have now only the canal left to act upon; and the operations on the canal may be divided into two great classes:—

(a.) Those in which the operator attempts to plug up the dilated canal. (b.) Those in which he tries to constrict it, by reuniting its separated sides.

(a.) Attempts to plug the canal have, in most cases, been made by invagination of the skin of the scrotum and its fascia. These have been very numerous and various in their adaptation of mechanical appliances, but have all been designed with the same object. Dzondi of Halle, and Jameson of Baltimore, incised lancet-shaped flaps of skin, and endeavoured to fix them by displacement over the ring. Gerdy invaginated a portion of scrotum and fascia into the enlarged canal, by the forefinger pushed it up, and secured it in its place by a thread passed from the point of his finger first through the invaginated skin, then through the abdominal walls, endeavouring to include the walls of the inguinal canal, causing the point of the needle to project some lines above the inguinal ring; the same process being effected with the other end of the thread on the other side of the finger, and the two ends which have been brought out near each other on the abdominal wall, being tied tightly over a cylinder of plaster. The ensheathed sac was then painted with caustic ammonia to excite inflammation, and a pad put on over all.

Signoroni modified this by fixing the invaginated skin by a piece of female catheter, retained in its place by transfixion by three harelip needles, tied by twisted sutures.

Wützer of Bonn, again, modified this, by substituting a complicated instrument, consisting of a stout plug in the inguinal canal, held in position by needles which are passed through the anterior wall of the canal in the groin. Compression between plug and compress, with the intention of causing adhesion between skin, fascia, and sac, is then managed by means of a screw. The plug is retained for about seven days.

Modifications of this method have been tried by Wells, Rothmund, and Redfern Davies, all aiming in the direction of simplicity; but by far the most simple and efficacious method on the Wützer principle yet devised is that of Professor Syme, which he described in the pages of the Edinburgh Medical Journal for May 1861, in which the invagination of integument is both simply and securely managed by strong threads, as in Gerdy's method, while a piece of bougie or gutta-percha, to which the threads are fixed, replaces Wützer's expensive and complicated apparatus. Sir J. Fayrer of Calcutta has had a very large experience of Wützer's method, and also of a plan of his own. Out of 102 cases by the latter method, 77 were cured, 9 relieved, 14 failed, and 2 died.148

Mr. Pritchard of Bristol has proposed an additional step in operations on the invagination principle, consisting in the stripping of a thin slip of skin from the orifice of the cutaneous canal, and then putting a pin through the parts to get them to unite, and thus close the aperture completely.

Now, what results follow these operations? At first they are almost invariably successful, but the complaint is that, in most cases, the rupture recurs. The principle is to plug up the passage by the mechanical presence of the invaginated skin, the plug being retained in position by adhesive inflammation between it and the edges of the dilated ring. But the ring is left dilated, or, indeed, generally its dilatation is increased; and as, on continued pressure from within, the new adhesions give way, or, as often happens, a new protrusion takes place in the circular cul-de-sac necessarily left all round the apex of the invagination, the still lax ring and canal offer no resistance to the protrusion.

(b.) The principle of constriction of the canal by reuniting its separated sides. This is the principle of the various methods introduced by Mr. Wood of King's College, and described by him in his most able and exhaustive work.149

He applies sutures through the sides of the dilated inguinal or crural canals, or umbilical openings, in such a manner as to insure their complete closure.

1. For inguinal hernia.—To stitch together the two sides of the canal with safety requires attention to several points—(1.) That it be done nearly, if not entirely, subcutaneously. (2.) That the protruding bowel should be kept out of the way, and not be transfixed by the needle. (3.) That the spermatic cord should be protected from injurious pressure.

These different indications are attained by Mr. Wood by a very ingenious mode of operating, which I can describe here only briefly, and for a full description of which I must refer to Mr. Wood's own monograph already alluded to.

For his first twenty cases Mr. Wood used strong hempen thread for the stitches; of late, however, he has proved the greater advantage of strong wire.

When a large old hernia in an adult is the subject of operation, it is thus performed by Mr. Wood:—The pubes being shaved, and the patient put thoroughly under the influence of chloroform, the rupture is reduced, and the operator's forefinger forced up the canal so as to push every morsel of bowel fairly into the abdomen. An assistant then commands the internal ring by pressure, to prevent return of the rupture.

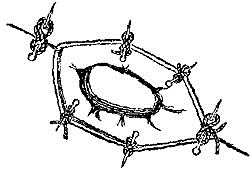

An incision is made in the scrotum over the fundus of the sac, large enough to admit a forefinger and the large needle used in the operation; the edges of the skin are to be separated from the fascia below for about one inch all round. The forefinger is then to be passed in at the aperture and pushed upwards, invaginating the detached fascia before it, and it must be made to enter the inguinal canal far enough to define the lower border of the internal oblique muscle stretched over it. A large curved needle (unarmed) is then passed on the finger as a guide, through the internal oblique tendon, the internal portion of the ring, and the skin of the abdomen; it is then threaded and withdrawn. Again, the needle (now with a thread) is guided by the finger and pushed through Poupart's ligament and the external pillar of the ring as before; while by a little manipulation its point is made to protrude through the same opening in the skin as before, a loop of thread is now left there, and the needle, still threaded, is again withdrawn. The next stitch, still guided on the finger, takes up the tendinous layer of the triangular aponeurosis covering the outer border of the rectus tendon close to the pubic spine; the point of the needle is then turned obliquely, so as to protrude through the original puncture in the skin a third time, the needle is then freed from the thread and withdrawn, thus leaving two ends and one intermediate loop of thread all at the one opening. These are so arranged that when they are tightened they draw together the sides of the canal; they are then secured over a compress of lint. The compress is removed and the stitches loosened, at dates varying from the third to the seventh day.

Mr. Wood now uses wire instead of thread. It has the advantage of greater firmness, excites less suppuration, and may be left much longer in situ, in consequence of which there is less risk of suppuration or pyæmia, and more chance of a good consolidation of the parts.

In congenital herniæ, and small ruptures in children and young boys, Mr. Wood uses rectangular pins in the following manner:—The scrotum being invaginated (without any incision through the skin) as far as possible up the canal, a rectangular pin, with a slightly-curved spear-pointed head, is passed through the skin of the groin to the operator's forefinger; guided by it, it is brought safely down the canal, and brought out through the skin of the scrotum just over the fundus of the hernial sac. A second pin is passed from the lower opening (still guided by the finger) in an upward direction, transfixing in its course the posterior surface of the outer pillar of the superficial ring, its point being brought out through, or at least close to, the first puncture made by the first pin. The pins are then locked in each other's loops—the punctures and skin protected by lint or adhesive plaster,—and the whole is retained by lint and a spica bandage. The pins should generally be withdrawn about the tenth day.

The author has now in many cases stitched with catgut the edges of the ring after the ordinary operation for hernia with the best effect.

2. For Femoral Rupture.—Cases suitable for operation are very infrequent; but should such a one be met with, Mr. Wood proposes the following operation on the same plan as the preceding. The hernia being fully reduced and the parts relaxed by position, an incision about an inch long should be made over the fundus of the tumour, and its edges raised so as to admit the finger fairly into the crural opening. The vein is then to be pushed inwards, and the needle passed through the pubic portion of the fascia lata of the thigh, and then through Poupart's ligament, appearing on the skin of the abdomen, a wire is then passed through the eye of the needle and hooked down, appearing through the wound, it is then withdrawn, and the needle again passed through the pubic portion of the fascia lata, but about three-quarters of an inch to the inside of the first puncture, then through Poupart's ligament again, and protruded through the same orifice in the skin; the other end of the wire is then hooked down as before, leaving a loop above, at the needle orifice, and two ends at the wound in the skin below. Both loops and ends must be managed as before.

The author after operating for the relief of strangulation in a case of very large femoral hernia in a girl aged 23, stitched up the neck of the sac, and also stitched it to Gimbernat's ligament. The result for some months was admirable, though the hernia had been a very difficult one to replace from its size, and had been long in the habit of coming down. Eventually protrusion occurred to a very slight extent, but a truss keeps it completely up.

3. For Umbilical Rupture.—The principle involved in Mr. Wood's operation for umbilical rupture is precisely the same as for inguinal and crural. It consists in stitching the two edges of the tendinous aperture by wire; the needle is passed on a sort of small scoop or broad grooved director, which at once invaginates the skin and protects the bowel. Two stitches are thus inserted on each side. For the ingenious method by which they are introduced subcutaneously, I must refer to the detailed description in Mr. Wood's monograph. The wires are thus twisted and tightened over a pad of lint or wood, drawing together the edges of the opening in the tendon.

Operations for Artificial Anus.—In children the condition known as imperforate anus may sometimes be remedied by exploratory operations in the perineum, guided by the protrusion caused by the distended intestine. There are other cases, however, in which the rectum, as well as the anus, seems to be deficient, and in which, from the want of protrusion, there is no warrant for attempting an operation there; in these the only chance of life that remains is in an attempt to open the bowel higher up.

In adults, again, absolute closure of the rectum and anus, and complete obstruction, may be the result of malignant disease, or even, very rarely, of simple organic stricture.

In such cases, where the patient is tolerably strong and yet evidently doomed from the complete obstruction, an attempt at the formation of an artificial anus is warrantable, and in many cases afford great relief, and prolongs life for months.

Without going into all the various positions proposed for such operations, I select the two most warrantable, which have borne the test of experience. These are—1. Colotomy in the left loin. This is applicable in the case of adults with rectal obstruction. 2. Colotomy in the left groin applicable in cases of imperforate anus and deficiency of rectum in infants.

1. Colotomy in the left loin, generally known by the name of Amussat's operation.—The patient is laid upon his face, a pillow placed under the abdomen, rendering the left flank prominent. A transverse incision should then be made at a level about two finger-breadths above the crest of the ilium, extending from the outer edge of the erector spinæ muscle forward for four or five inches, according to the fatness of the patient; the muscles must then be carefully divided till the transversalis fascia is exposed. It is then to be pinched up and divided, as in the operation for strangulated hernia. The muscular wall of the colon uncovered by peritoneum is then in most cases very easily recognised from its immense distension. The bowel should then be hooked up by a curved needle, two or three points at least secured to the margins of the wounds by stitches, and then the bowel should be opened by a longitudinal incision of at least an inch in length. When the distension has been great, there is generally a rush of fluid fæces, which must be provided for, special care being taken lest any get into the cavity of the peritoneum.

Fig. xxxiii. 150

2. Colotomy in the left groin, for absence of anus and deficiency of rectum in newly born infants.—The dissections of Curling, Gosselin, and others have shown that in infants the operation of lumbar colotomy is very difficult, and its results uncertain, while it is comparatively easy to open the colon in the left groin. Huguier, again, has shown that in certain cases the colon is not to be found in the left groin, but is accessible in the right groin. This abnormality seems, as shown by Curling, to occur not oftener than once in every ten cases.

Operation.—An oblique incision from an inch and a half to two inches in length should be made in the left iliac region above Poupart's ligament, extending a little above the anterior-superior spinous process of the ilium. The fibres of the abdominal muscles should be divided on a director passed beneath them, and the peritoneum should next be cautiously opened to a sufficient extent. The colon will most likely protrude, but if small intestine appear the colon must be sought for higher up. A curved needle armed with a silk ligature should be passed lengthways through the coats of the upper part of the colon, and another inserted in the same way below, and the bowel, being drawn forwards, should then be opened by a longitudinal incision. The colon must afterwards be attached to the skin forming the margin of the wound by four sutures at the points of entry and exit of the needles.

Operation for the Removal of an Artificial Anus, in cases where the bowel is patent below.—After the operation for hernia in a case where the bowel is gangrenous, the only hope of the patient's recovery consists in the formation of adhesions between the bowel and the external wound, and the presence, for a time at least, of an artificial anus. If adhesions do form, and the patient recovers, it becomes a matter of great importance for his future comfort that the canal of the intestine should be re-established, and the fistulous opening allowed to close. This, however, is by no means easy, as even when the portion of intestine destroyed has been very small, a septum or valve remains which directs the contents of the bowel outwards, and so long as it exists is an effectual obstacle to any of the fæcal contents passing into the distal portion of the bowel. This septum or éperon is formed by the mesenteric side of the two ends of the bowel. To destroy this without causing peritonitis is the aim of the surgeon, and it is not an easy matter to accomplish. To cut it away would at once open the peritoneal cavity, so the mode of treatment now adopted in the rare cases where it is necessary is that recommended by Dupuytren. The principle of it is to destroy the éperon by pressure so gradual as to cause adhesive inflammation between the two surfaces, and thus seal up the cavity of the peritoneum, before the continuance of the same pressure shall have caused sloughing of the septum. This is managed by the gradual approximation by a screw of the blades of a pair of forceps, to which Dupuytren gave the name Enterotome. The process, which extends over days and weeks, must be carefully watched lest the inflammation go too far.

Plastic operations are occasionally required to close the opening after the passage is restored. For a good example of such an operation see Edin. Med. Journal for August 1873, in which Mr. John Duncan describes a case.

CHAPTER XII.

OPERATIONS ON PELVIS

Lithotomy.—However interesting and even instructive it might be, any history of the various operations for the removal of calculi from the bladder would be quite out of place in a manual such as this. It will be sufficient here to describe the operations recommended and practised in the present day.

There are three different situations in which the bladder may be entered for the purpose of removing a calculus:—

1. The perineum, where access is gained through the urethra, prostate, and neck of the bladder.

2. Above the pubes, where the portion of bladder not covered by peritoneum is opened from above.

3. From the rectum.

1. Lithotomy through the Perineum, by far the most frequent position for the operation.—Very various methods for its performance have been devised, differing in the nature and shape of the instruments employed, the direction and size of the incisions, the nature of the wound; but all resemble each other in certain very cardinal and important particulars. Thus all agree that it is absolutely necessary to enter the bladder at one spot—the neck of the bladder; and that to do this safely the urethra must be opened, and some instrument previously introduced by the urethra is to be used as a guide for the knife. But an instrument in the urethra and bladder is surrounded for at least an inch of its course by the prostate; and thus the knife, gorget, or finger, which, guided by the instrument in the urethra, is intended to cut or dilate the entrance to the bladder for the purpose of allowing the calculus to be removed, cannot do this without also cutting or dilating this prostate gland. Experience has proved that much of the success of the operation depends upon the position and amount of incision made in this prostate gland. But it might be asked, Why can we not enter the bladder by one side, avoiding altogether its neck and this prostate gland? For this, among other reasons, that the bladder normally contains, and so long as the patient lives must contain, a certain quantity of a very irritating fluid. It is surrounded by the loose areolar tissue of the pelvis, into which, if any of this fluid escapes, abcesses will form and death probably ensue; this result will almost certainly follow any opening made into the bladder except at one spot. This spot is the neck of the bladder. Why does urinary infiltration not occur there? Because the fascia of the pelvis (which when entire can resist infiltration) is prolonged forwards at the neck of the bladder, over the prostate (Fig. xxxiv. pf), for which it forms a very strong funnel-like sheath. So long as this sheath is not cut where it covers the sides of the prostate, urinary infiltration of the pelvis is impossible, the urine being carried forwards and fairly out of the pelvis in this urine-tight funnel.