полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

A Manual of the Operations of Surgery

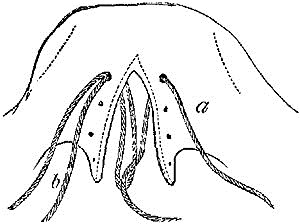

1. That the edges of the fissure should be brought together without strain or tightness. In small fissures this can generally be done easily enough; but where the fissure is extensive, some means must be used to relieve tension. For this, Sir William Fergusson long ago proposed the division of the palatal muscles, the levator, tensor, and palato-pharyngeus muscle of each side. The incisions in the palate for this purpose certainly aid apposition, but many surgeons entertain doubts whether the division of the muscles has much to do with the good result, and believe that the simple incisions in the mucous membrane, in a proper direction, are all that is required (see Fig. xxix.).

Fig. xxix. 123

2. That the edges of the fissure be made raw, so as to afford surfaces which will readily unite. Complicated instruments, such as knives of various strange shapes, have been devised for this purpose; an ordinary cataract knife, very sharp, and set on a long handle is perhaps the best. It greatly facilitates the section if the parts are tense, so the point of the uvula should be seized by an ordinary pair of spring forceps, and drawn across the roof of the mouth, while the knife should enter in the middle line, a little above the apex of the fissure, and make the cut downwards as in harelip.

3. That sutures should be inserted to keep the edges in apposition, yet not so tightly as to cause ulceration. They may be either of metal, silver being preferable, or of fine silk well waxed. The metallic sutures are now generally preferred. Some dexterity is required in their introduction, and various instruments have been devised; the best seems to be a needle with a short curve fixed on a long handle, which should be entered on the (patient's) left side of the fissure in front, and brought out on the right side.

If silk sutures be used, the chief difficulty, that of passing the thread through the second side from behind forwards, can be avoided in the following manner.124 A curved needle is passed through one side of the fissure, and then towards the middle line, till its point is seen through the cleft. One of the ends of the thread is then seized by a long pair of forceps, and drawn through the cleft; the needle is then withdrawn, leaving the thread through the palate, and both ends are brought outside at the angle of the mouth. Another needle is then passed through a corresponding point at the opposite side of the palate, till its point again appears at the cleft; this time a double loop of the thread is also brought out through the cleft by the forceps into the mouth. If then the single thread of the first ligature which is in the cleft be passed through the loop of the second one also in the cleft, it is easy, by withdrawing the loop through the palate, to finish the stitch (see Fig. xxix.). All the stitches should be passed and their position approved before any one be tied, and it is most convenient to secure them from above downwards. To prevent confusion, each pair of threads after being inserted should be left very long, and brought up to a coronet fixed on the brow, which is fitted with several pairs of hooks numbered for easy reference. This will prevent twisting of the threads or any mistake in tying.

Fissure of the Hard Palate.—This may vary in extent from a very slight cleft in the middle line behind, up to a complete separation of the two halves of the jaw, including even the alveolar process in front, and sometimes complicated with harelip.

To close such fissures by operation is difficult, as the breadth of the cleft is so great as to prevent the apposition of the edges when prepared, without such extreme tension as quite prevents any hope of union. Through the researches of Avery, Warren, Langenbeck, and others, a method has been discovered of closing such fissures by operation, which, though certainly not easy, is, when properly performed, generally successful.

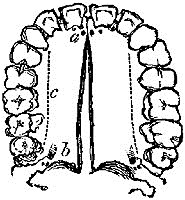

Operation.—In addition to the usual paring of the edges of the cleft, an incision is made on each side of the palate, extending "from the canine tooth in front to the last molar behind,"125 along the alveolar ridge (Fig. xxx.). The whole flap between the cleft and this incision on each side is then to be raised from the bone by a blunt rounded instrument slightly curved. With this the whole mucous membrane and as much of the periosteum as possible should be completely raised from the bone, attachments for nourishment of the flap being left in front and behind where the vessels enter.

Fig. xxx. 126

The flaps thus raised will be found to come together in the middle line, sometimes even to overlap, and, when united by suture, form a new palate at a lower level than the fissure, experience having shown that in cases of fissure the arch of the palate is always much higher than usual. The flaps do not slough, being well supplied with blood, unless they have been injured in their separation.

The edges must be carefully united by various points of metallic suture, and the fissure of the soft palate closed at the same sitting, unless the patient has lost much blood, or is very much exhausted with the pain. The stitches may be left in for a week, or even ten days, unless they are exciting much irritation. The patient must exercise great self-control and caution in the character of his food and his manner of eating for ten days or a fortnight after the operation.

Excision of Tonsils.—To remove the whole tonsil is of course impossible in the living body, the operation to which the name of excision is given being only the shaving off of a redundant and projecting portion. When properly performed it is a very safe, and in adults a very easy operation, but in children it is sometimes rendered exceedingly difficult by their struggles, combined with the movements of the tongue and the insufficient access through the small mouth. Many instruments have been devised for the purpose of at once transfixing and excising the projecting portion; some of them are very ingenious and complicated. By far the best and safest method of removing the redundant portion is to seize it with a volsellum, and then cut it off by a single stroke of a probe-pointed curved bistoury; cutting from above downwards, and being careful to cut parallel with the great vessels.

The ordinary volsellum is much improved for this purpose by the addition of a third hook in each tonsil placed between the others, with a shorter curve, and slightly shorter; this ensures the safe holding of the fragment removed, and prevents the risk of its falling down the throat of the patient.

If both tonsils are enlarged they should both be operated on at the same sitting, and the pain is so slight that even children frequently make little objection to the second operation. Bleeding is rarely troublesome if the portion be at once fairly removed, but if in the patient's struggles the hook should slip before the cut is complete, the partially detached portion will irritate the fauces, cause coughing and attempts to vomit, and sometimes a troublesome hæmorrhage.

The plentiful use of cold water will generally be sufficient to stop the bleeding, though cases are on record in which the use of styptics, or even the temporary closure of a bleeding point by pressure, has been necessary.

M. Guersant has operated on more than one thousand children, with only three cases of any trouble from hæmorrhage, while four or five out of fifteen adults required either the actual cautery or the sesqui-chloride of iron.127

CHAPTER IX.

OPERATIONS ON AIR PASSAGES

Operations on the Larynx and Trachea.—The great air passage may be opened at three different situations, and to the operations at these different places the following names have been given:—

Laryngotomy, when the opening is made in the interval between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages, through the crico-thyroid membrane.

Laryngo-tracheotomy, when the cricoid cartilage and the upper ring of the trachea are divided.

Tracheotomy, when the trachea itself is opened by the division of two, three, or more rings.

Of these the last, tracheotomy, is by far the most frequent, important, difficult, and dangerous, and requires a very detailed description. Chassaignac128 says "the only really rational operation for the opening of the air passages by the surgeon is tracheotomy."

Tracheotomy.—Anatomy.—Between the cricoid cartilage and the level of the upper border of the sternum, the middle line of the neck is occupied by the upper portion of the trachea. Its depth from the surface varies, gradually increasing as the trachea descends, and varying very much according to the fatness, muscularity, and length of the neck. It is, however, almost subcutaneous at the commencement below the cricoid, and on the level of the sternum it is in most cases at least an inch from the surface, in many much deeper. Again, its length varies, even in the adult, from two and a half to three, or even four inches. This is important, as affecting the simplicity of the operation, which, as a rule, is easier the longer the neck is.

The trachea has most important and complicated anatomical relations—some constant, others irregular.

1. The carotid arteries and jugular veins lie at either side, but, where these are regular in their distribution, do not practically interfere in a well-conducted operation.

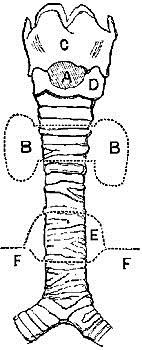

2. The thyroid gland lies in close relation to the trachea, one lobe being at each side (Fig. xxxi. B B), and the isthmus of the thyroid crosses the trachea just over the second and third cartilaginous rings. In fat vascular necks, or where the thyroid is enlarged it may occupy a much larger portion of the trachea. The position of the isthmus practically divides the trachea into two portions in which it is possible to perform tracheotomy. Both have their advocates, but the balance of authority tends to support the operation below the thyroid. A separate notice of each will be required immediately.

Fig. xxxi. 129

3. The muscles in relation to the trachea are the sterno-hyoid and sterno-thyroid of each side. The latter are the broadest, are in close contact across the trachea by the inner edges below, but gradually diverge as they ascend the neck. In thick-set, muscular necks, however, they are in close contact for a considerable distance, and require to be separated to give access to the trachea.

The arteries are in most cases unimportant; no named branch of any size ought to be divided in the operation. However, occasionally very free bleeding may result from the division of an abnormal thyroidea ima running up the trachea to the thyroid body from the innominate, or even from the aorta itself.

The veins are very numerous and irregularly distributed. There is generally a large transverse communicating branch between the superior thyroid veins just above the isthmus. The isthmus itself has a large venous plexus over it. Below the isthmus the veins converge into one trunk (or sometimes two parallel ones) lying right in front of the trachea.

4. The last anatomical point which may give trouble in normal necks is the thymus, which is present in children below the age of two, and covers the lower end of the trachea just above the level of the sternum. Where this is not only not diminished, but enlarged, as it sometimes is in unhealthy children, it may give a very great deal of trouble, rolling out at the wound and greatly embarrassing proceedings.

Abnormalities are very various and sometimes very dangerous: vessels crossing the trachea, as the innominate did in Macilwain's case,130 or where two brachiocephalic trunks are present, as recorded by Chassaignac.131 One of the most frequent dangers to be guarded against is a possible dilatation of the aorta or aneurism of the arch. This may very possibly, as happened in one case to the author, give rise to suffocative paroxysms from its pressure on the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Tracheotomy may be deemed necessary, and there is a great risk, unless proper precautions be taken, of wounding the aorta, where it passes upwards in the jugular fossa. In the author's case the vessel had actually to be pushed downwards by the pulp of the forefinger while the trachea was opened, the knife being guided on the back of the nail of the same finger.

The Operation.—In a work of this kind it would be utterly impossible to go at all into the subject of what diseases, injuries, etc., warrant or require the operation. It is enough to describe the various methods of operating, their dangers and difficulties.

1. The operation above the isthmus of the thyroid.—A spot about a quarter or half of an inch in vertical diameter between the cricoid cartilage (Fig. xxxi.) and thyroid isthmus.

Advantages.—It is near the surface, the vessels are few and comparatively small. It is most suitable in cases of aneurism.

Professor Spence132 gives his sanction to the high operation in adults with thick short necks when the operation is performed for ulceration or papilloma of larynx or for spasm from aneurism, the low operation being still best in cases of croup or diphtheria.

Disadvantages.—The space is too small, requires very considerable disturbance of the thyroid isthmus, or actual division of it. It is too near the point where the disease is; so much so, that in most cases of croup or diphtheria it would be perfectly useless. However, if required, or if the operation lower down be contra-indicated, this may be performed easily enough. A straight incision being made in the middle line about one inch and a half in length, expose the upper ring by careful dissection, if possible draw aside the veins, and depress the thyroid isthmus, divide the rings thus exposed, and introduce the tube.

The operation below the isthmus.—This, though more difficult in its performance, is a much more scientific and satisfactory operation. Considerable coolness and a thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the part are absolutely required.

The patient being in the recumbent posture, the shoulders should be well raised, and the head held back so as to extend the windpipe, and thus bring it as near as possible to the surface. A pillow, or the arm of an assistant, behind the neck will be of service.

N.B.—Be careful lest too great extension by an anxious assistant, accompanied by closure of the mouth, should choke the patient (whose breathing is of course already much embarrassed) before the operation be begun.

Chloroform may occasionally be given, and, if well borne, renders the operation very much easier than it would otherwise be. An incision must then be made exactly in the median line of the neck, from a little below the cricoid cartilage, almost to the upper edge of the sternum; at first it should be through skin only, then the veins will be seen, probably turgid with dark blood; the larger ones should be drawn aside, if necessary divided, the bleeding stopped by gentle pressure. The deep fascia must then be cautiously divided, great care being taken to keep exactly in the middle line, and the contiguous edges of sterno-thyroid muscles separated from each other by the handle of the knife. A quantity of loose connective tissue, containing numerous small veins, must now be pushed aside, the thyroid isthmus pressed upwards, still with the handle of the knife. The forefinger must then be used to distinguish the rings of the trachea. If there is much convulsive movement of the larynx and trachea, they should be fixed by the insertion of a small sharp hook with a short curve, just below the cricoid cartilage, and this should be confided to an assistant. The surgeon should then, with the forefinger of his left hand, fix the trachea, and open it by a straight sharp-pointed scalpel, boldly thrusting it through the rings with a jerk or stab, the back of the knife being below, and divide two or three of the rings from below upwards. Any attempt to enter the trachea slowly with a blunt knife or trocar will probably be unsuccessful, as the rings, especially in children, give way before the knife, which merely approximates the sides of the trachea without opening it.

Question of Hæmorrhage.—It is often a question of some importance, and one which sometimes it is not easy to settle, how far attempts should be made completely to arrest the venous hæmorrhage before opening the trachea.

On the one hand, if not arrested, besides the risk of weakening the patient, we have to dread the much more serious complication of the admission of blood into the wound. And this is very serious in a patient whose respiration has already been much impeded, whose lungs are probably engorged, and who has certainly, by the mere existence of a wound in his trachea, lost the power of coughing properly; it must never be forgotten that a quantity of blood so trifling as to be at once ejected by a single cough in the case of a healthy chest, may be a fatal obstacle to respiration in one already weakened by disease. Thus any well-marked arterial hæmorrhage from cut branches, or from the isthmus of the thyroid, must certainly be arrested prior to opening the trachea. Besides this, blood once having entered the bronchi is apt to extend into their smaller ramifications and prove a cause of death, by acting as a local irritation, and setting up intra-lobular suppurative pneumonia. The author has found this to be the case both after tracheotomy and still more frequently in suicide by cut throat.

But, on the other hand, it is equally true that there is almost always a considerable amount of oozing from small venous radicles divided during the operation, which depends simply on the great venous engorgement resulting from the obstruction to the respiration, so that while to attempt to tie every point would be simply endless, we may be almost certain that the oozing will cease whenever the trachea is opened, and respiration fairly improved. Slight pressure on the wound is generally sufficient to stop the bleeding till the venous engorgement has disappeared.

Of late years many tracheotomies have been done bloodlessly by use of the thermo-cautery, for division of the soft parts, but the subsequent sloughing of the wound is a great objection to this method.

In cases of extreme urgency, all such minor considerations as suppression of venous oozing must be ignored, and the trachea simply opened as rapidly as possible. I had once to perform the operation after respiration had entirely ceased, and no pulse could be felt at the wrist, with no assistance except that of a female attendant. Merely feeling that no large arterial branch was in the way, I cut straight through all the tissues, opened the trachea, and commenced artificial respiration. The patient eventually recovered.

Question of Tubes, etc.—Once the trachea is opened, the next question is, How is the opening to be kept pervious? For the moment the handle of the scalpel is to be inserted in the wound, so as to stretch it transversely; this will probably suffice to allow of the escape of any foreign body. But where, to admit air, the wound is to be kept open, how is this to be done? It used to be advised that an elliptical portion of the wall of the trachea be removed; this, though succeeding well enough for a time, was unscientific, as the wound always tended to cicatrise, and ended of course in permanent narrowing of the canal of the trachea. It may be necessary thus to excise a portion of the trachea, in cases where it is very intolerant of the presence of a tube. Such a case is recorded by Sir J. Fayrer of Calcutta.133 Not much better is the proposal to insert a silk ligature in each side of the wound, and by pulling these apart thus mechanically to open the wound. This also is evidently a merely temporary expedient.

Various canulæ and tubes have been proposed. The ones recommended by the older surgeons had all one great fault; they were much too small, and were many of them straight, and thus liable to displacement. The smallness of their bore was their greatest objection, and Mr. Liston conferred a great benefit on surgery by his insisting upon the introduction of tubes with a larger bore, and with a proper curve, so as thoroughly to enter the trachea. The tube ought to be large enough to admit all the air required by the lungs, without hurrying the respiration in the least.

There is a mistake made in the construction of many of the tubes even of the present day; the outer opening is large and full, while for convenience of insertion the tube tapers down to an inner opening, admitting perhaps not one-half as much air as the outer one does.

It must be remembered that for some days there is great risk of the tube becoming occluded, by frothy blood or mucus, especially in cases of croup, and in children. To prevent this a double canula will be found of great service, providing only that it be remembered that the inner canula, not the outer merely, is to be made large enough to breathe through, and that the inner should project slightly beyond the outer one.

The inner one can thus be removed at intervals and cleansed, by the nurse, without any risk of exciting spasm or dyspnœa by its absence and reintroduction.

After-treatment.—The after-treatment of a case in which tracheotomy has been performed demands great care and many precautions. For the first day or two the constant presence of an experienced nurse or student is always necessary to insure the patency of the tube. The temperature of the room should be equable and high, and it seems of importance that the air should be kept moist as well as warm by the use of abundance of steam.

A piece of thin gauze, or other light protective material, should be placed over the mouth of the tube, to prevent the entrance of foreign bodies.

In cases where the operation has been performed for some temporary inflammatory closure of the air passage, retention of the tube for a few days may suffice. It may then be removed, but it must be remembered that the wound will generally close with great rapidity, so that it is as well to be quite sure of the patency of the natural passage before the artificial one is allowed to close by the removal of the tube.

In cases where from long-standing disease or severe accident the larynx is rendered totally unfit for work, and the tube has to be worn during the rest of the patient's life, care must be taken (1.) lest the tube do not fit accurately, in which case it may ulcerate in various directions, even into the great vessels;134 (2.) lest the tube become worn, and lest the part within the windpipe fall into the trachea and suffocate the patient.135

Laryngotomy.—As a temporary expedient in cases of great urgency, where proper instruments and assistants are not at hand, laryngotomy is occasionally useful, though from the want of space without encroaching on the cartilages of the larynx, and from its close proximity to the disease, laryngotomy is by no means a suitable or permanently successful operation.

In the adult, especially in males with long spare necks, the operation itself is exceedingly easy to perform. The crico-thyroid space (Fig. xxxi. a) is so distinctly shown by the prominence of the thyroid cartilage, and is so superficial that it is quite easy to open it in the middle line with a common penknife, there being merely the skin and the crico-thyroid membrane to be cut through, with very rarely any vessel of any size. The opening can then be kept patent by a quill or a small piece of flat wood. This simple operation has in many cases, where a foreign body has filled up the box of the larynx, succeeded in saving life, and even in cases of disease I have known it useful in giving time for the subsequent performance of tracheotomy.

Easy as it appears and really is, cases are on record in which the thyro-hyoid space has been opened instead of the crico-thyroid, such operations being of course perfectly useless.

The incision is best made transversely.

Laryngo-Tracheotomy.—This modification consists in opening the air passage by the division of the cricoid cartilage vertically in the middle line, along with one or two of the upper rings of the trachea.