полная версия

полная версияA Manual of the Operations of Surgery

N.B.—The ends of the ligature must be left sufficiently long to avoid any risk of their being drawn out of sight into the substance of the cornea, or even into the ball, by retraction of the fibres of the iris.

Corelysis.—Freeing of the Pupil.—An operative procedure for separating posterior adhesions of the iris to the lens. In it the surgeon hopes to act, not on the iris, as in the operations for artificial pupil, but only on the bands of false membrane which distort the pupil.

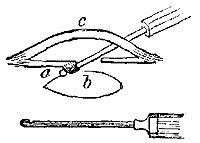

The operation is briefly as follows:—The eye being firmly held by a wire speculum, and forceps pinching up the conjunctiva, a broad needle is passed rapidly through the cornea at a point which may give easy access to the adhesion to be torn through. This point is generally at the opposite margin of the irregular pupil, so that the needle may pass through the cornea in front of the one side of the iris, then through the orifice of the pupil, so as to reach the back of the other side. The needle is withdrawn gradually, so as to lose as little of the aqueous humour as possible, and then the spatula hook, called after the inventor of the operation, Mr. Streatfeild, is introduced. It is used first as a spatula, that is, with its blunt, though polished edge, to separate the adhesions, and if this is unsuccessful, as a hook (Fig. xiv.), so as to catch and tear them. In cases which resist the instrument used in both of these ways, Mr. Streatfeild has used very fine canula-scissors to cut the adhesions.91 Such a further complication of the operation practically alters its character into an operation for artificial pupil, q.v.

Fig. xiv. 92

Iridectomy.—In cases of acute glaucoma, irido-choroiditis, and all deep inflammations of the eye in which the ocular tension is increased, also in certain cases of flap extraction already alluded to, the operation of iridectomy as originally proposed by Von Graefe will be found of use.

Operation.—The patient recumbent, and the eye absolutely fixed by speculum and forceps, a linear incision, varying in length from one-sixth to one-fourth of an inch, is made just at the margin of the cornea. The point of election is the upper pole of the cornea. The lens must not be wounded. The best instrument for making the section is an ordinary linear extraction knife, bent at an angle to admit of its being introduced from above. The iris will protrude through the wound, or, if adherent, must be drawn out by forceps, and then is to be cut off with scissors. The operation is rarely successful, unless a third, or at least a fourth, of the iris be removed.

Excision of a Staphylomatous Cornea.—There are certain cases in which the whole or greater part of the cornea bulges forward in a great blue projecting tumour. It is very ugly as it protrudes between the lids and prevents their closure; besides this, from its exposure it frequently inflames, even ulcerates, and has a most injurious effect on the other eye. In the cases suitable for operation vision is completely gone, without hope of its restoration by any operative procedure.

The best thing for the patient is to have just enough of the staphyloma removed to enable the remains of the eyeball to form a good stump for an artificial eye. Various means have been suggested for doing this, varying in extent and severity from a mere shaving off the apex of the staphyloma to excision of the whole eyeball.

By far the best method of operating is the one proposed and practised by Mr. Critchett.

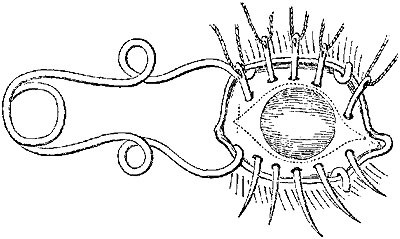

Fig. xv. 93

Fig. xvi. 94

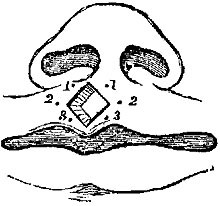

The object of it is to remove an elliptical portion of the front of the staphyloma, or the whole staphyloma, when it is possible, and at the same time to prevent as far as possible the escape of the vitreous.

Operation.—Three, four, or five small curved needles armed with thread are passed through the staphyloma from above downwards, being each entered a little above the line of the intended upper incision, and brought out a little below the line of the intended lower one (Fig. xv.)

To remove the included elliptical portion, Mr. Critchett pierces the sclerotic with a Beer's knife, just in front of the tendinous insertion of the external rectus. Through this incision a pair of probe-pointed scissors is introduced, and the piece cut just within the points of the needles. On the removal, the needles, which have retained the vitreous by their pressure, are drawn through and the threads cautiously tied.

Union by first intention very often occurs, and an excellent stump is left with a narrow depressed transverse cicatrix95 (Fig. xvi.)

Extirpation of the Eyeball.—1. Of the Eyeball only.—A circular incision should be made with curved scissors through the conjunctiva, a little beyond the corneal margin, then, beginning with the external rectus, muscle after muscle should be raised with the forceps, and divided, after which the optic nerve is cut through with the scissors. A slight preliminary extension outwards of the optic commissure will facilitate the dissection, and must be secured with metallic sutures; any vessels should be tied, and the orbit filled up with a light compress of charpie secured with a bandage.

2. Of the contents of the Orbit.—This may be required for malignant disease, but with a very poor prognosis. The optic commissure should be freely divided, and then, by bold strokes of curved scissors, or curved probe-pointed bistoury, the orbit may be fairly emptied by scooping out its contents. Even the periosteum may require to be scraped off, and the optic nerve divided as far back as possible. The hæmorrhage may be pretty smart, but can generally be easily checked by compresses; if necessary, these can be soaked in the solution of the perchloride of iron.

The author has done this operation many times, in cases extensive and of old standing, for malignant disease, melanotic and encephaloid. All have recovered, and in no instance has there been any trouble in stopping the bleeding.

CHAPTER VI.

OPERATIONS ON THE NOSE AND LIPS

Rhinoplastic Operations.—The operations for the restoration or repair of lost or mutilated noses are so various, and the minuteness of detail necessary for full description of them so great, that a complete account in a manual such as this is impossible; a brief notice of some of the most important varieties of the operation is all that can be given.

Principles.—1. It is necessary in every case that a suitable edge be prepared on which to fix the flap of skin, however obtained. To be suitable, this edge, should be (a) made in healthy skin, not in old or weak cicatrices; hence no trace of the original disease should be left; (b) it should be made thoroughly raw, by the removal of an appreciable amount of its edge; it should be pared, not merely scraped.

2. It is useless to attempt to restore a nose unless the patient is in good general health, well nourished, and perfectly free from all remains of disease in the nose or its neighbourhood. The flaps which are to form the new nose may be obtained either from (1.) the cheeks; (2.) the forehead; (3.) a distant part either of the patient or of another person.

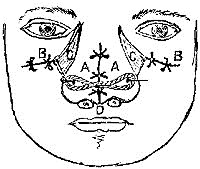

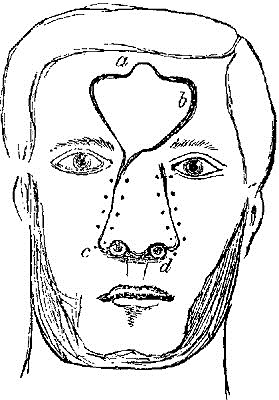

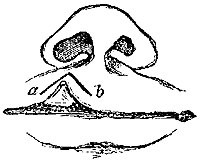

(1.) From the Cheeks.—When the cheeks are healthy, and specially if they are tolerably full and lax, the flaps from the cheeks produce much the most satisfactory result. As performed by Mr. Syme, the operation consists in the shaping of two equal flaps (a, a) from the skin of the cheek at each side, having the attachment above. A site for each flap is formed by the careful paring away of the whole thickness of the edge of the cavity of the lost organ (see Fig. xvii.)

Fig. xvii. 96

The flaps are then raised from their attachments to the upper jaw-bone, and approximated in the middle line by several points of metallic suture and the outer edges stitched to the raw surface on each side at a proper distance from the nasal orifice. If any septum remains of the old nose, it may be made very useful as a fixed point, a straight needle being thrust through one flap close to its outer lower edge, then through the septum, and out at a corresponding point of the other flap. The edges of the wound left in the cheek at each side can generally be, to a certain extent, approximated by silver stitches (b, b) and the triangular portion (c, c), which is necessarily left to heal by granulation, proves an advantage, as by its depression it enhances the apparent height and prominence of the new organ. The cavity should be very gently distended with lint, and may be supported by the blades of a small pair of forceps, applied so as to embrace the nose.

(2.) From the Forehead.—The Indian operation may be used as a last resource, in cases where, from disease, the cheeks also have suffered, and are not to be trusted to for flaps.

Operation.—1. It should be decided as to the shape and size of the portion of skin necessary, by fitting on pieces of soft leather or moulding wax. To allow for shrinking, the flap should be made at least one-third larger than is at first apparently necessary. The exact boundaries of the flap to be raised should then be marked out on the forehead by lightly pencilling it with nitrate of silver, the mark from which is not effaced by blood, as is sure to be the case with an ink line. Various shapes have been proposed for the flap varying in length of neck, in the shape of the angles, and especially in the arrangements made for the formation of a columna. Some (as Liston) prefer afterwards to provide for the columns separately, by a flap raised from the upper lip in a subsequent operation. The flap is then to be raised from the forehead, care being taken not to injure the periosteum. The incision is to be carried lower down on the side (generally the left), to which the flap is to be twisted. The flap is then to be brought round (Fig. xviii.) and carefully fitted on to the edges previously prepared for its reception. The neck must be left as lax as possible, lest by tight twisting the supply of blood be cut off, and the flaps thus deprived of nourishment. Both silk and metallic sutures are recommended. Hamilton of Dublin,97 after a large experience of both, prefers the former.

Fig. xviii. 98

There are various risks; sloughing of the whole flap at once, shrinking of it after weeks or even months; certain inevitable drawbacks, as the cicatrix on the forehead, the very various and ludicrous changes of colour to which the new organ is subject,—these cannot be remedied by further operation. Two points generally require a second use of the knife a few weeks after:—(1.) The neck of the flap is sure to be redundant and prominent, but can be pared. (2.) The columna almost always requires improving, and, in Liston's method, to be made. He pared the inner surface of the apex of the nose, and then raised a central flap of the lip in the middle line, about a quarter of an inch broad, and extending from the remains of the old septum to the free border, raising it from the gum, and stitched the free end of it to the prepared apex, bringing together the two divided portions of the lip by ordinary harelip sutures. Tho columna, if redundant, could be shaved down, and it was found that the mucous surface very quickly became like skin on exposure.

For other points with regard to the operation, reference may be made to the works of Liston and Skey, and Hamilton's monograph, referred to above.

Note.—The tongue and groove suture proposed by Professor Pancoast, and recommended by Professor Gross, is said to be specially suitable for such plastic operations. It is very complicated, as it requires one edge to be bevelled to a wedge shape, the other being grooved to include the wedge, thus opposing four raw surfaces, which are retained in contact by being transfixed by fine silk sutures.

(3.) There are certain cases in which neither cheeks nor forehead are available for flaps, and yet the patients press very much for some operation. If they have patience and determination, the Taliacotian or Italian operation may be attempted.

Without going into detail, the principle of it is as follows:—1. A piece of skin of suitable size was marked out over the left biceps, and defined by two longitudinal incisions, and raised from the subcutaneous cellular tissue, thus being left attached by its two ends only; a piece of linen was pulled below it. 2. After a few days the upper end was also divided, and the flap thus contracted. In a few days more the sides of the old nose were made raw, and the upper free surface of the flap also made raw and stitched to them, the arm being fastened up by a most elaborate series of bandages. 3. After a fortnight in this position, the last attachment of the flap to the arm was severed, and the new nose could then be modelled at pleasure.

The literature of the subject is exceedingly curious, especially the cases in which the new material was obtained from an accommodating friend or servant.

Operative Treatment of Lupus.—We may here notice a mode of treatment which has admirable results. The patient being put deeply under an anæsthetic, the surgeon with a sharp spoon carefully pares away all the diseased tissues, and then destroys the base either by nitric acid or a strong solution of chloride of zinc. The author has done this in a great number of cases with excellent effect.

Nasal Polypi, Removal of.—Of these there are different kinds.

1. Ordinary Mucous Polypi.—These grow from the spongy bones, generally the superior one, are non-malignant in their character, soft and vascular, often fill up the whole of both nasal cavities, and frequently hang down behind into the pharynx. The practical point to remember is that, however large and numerous they may be, they invariably have their origin from a comparatively limited spot, the edge of the spongy bone, and always hang from a narrow neck. Hence the treatment is easy and satisfactory, if the neck be attacked, and not the body of the tumour.

Slightly curved, narrow-bladed forceps should be passed along by the side of the superior spongy bone, with their blades open, till the neck of the polypus is seized. Holding it firmly, the forceps should then be slowly twisted round till the neck is destroyed and the polypus detached. This should be repeated till the patient can blow freely through both nostrils. If attempts are made to seize the body of the polypus, it will break down under the forceps, bleed, and give much trouble.

2. The Fibrous Polypus.—This form is fortunately much more rare than the other. It is almost invariably single, is attached to the posterior margin of the nares by a narrow but very strong root, is extremely firm in consistence, may grow to a large size so as to obstruct both nostrils, generally gives rise to severe and frequent hæmorrhages. The hæmorrhage during any attempt to remove it is generally of the most severe character, but ceases immediately on its complete detachment.

We owe nearly all that we do know about the treatment of this form of polypus to Mr. Syme. His method is—By the ordinary polypus forceps described already, he seized the tumour through the nostril, and then with the fore and middle fingers of the left hand introduced behind the soft palate, he attacked the point of attachment, and by his nails, aided by the forceps, detached it from its narrow base.99

3. Malignant Polypi should not be meddled with unless it is absolutely certain that the whole of the bone from which they grow can be removed also. This is very rarely the case. (See Excision of Superior Maxilla.)

Operations on the Lips.—1. Epithelial cancers of the lower lip are very frequent, and require removal.

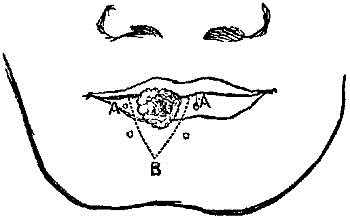

Fig. xix. 100

If the tumour or ulcer is small, and involves a considerable thickness of the lip, it is most easily removed by a V-shaped incision (Fig. xix. A B A). Its shape permits the most accurate apposition of the cut surfaces; and if the lips are full and the tumour small, very slight trace of the operation will remain.

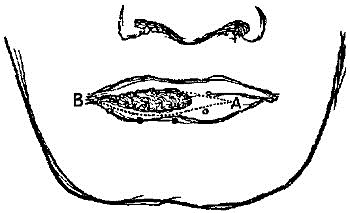

Again, if the tumour be more extensive, involving a large portion of the prolabium, and yet not extending deeply into the substance of the lip, it may be very easily removed by a pair of curved scissors, applied in the direction shown in the diagram (Fig. xx. A B). The skin must then be stitched to the mucous membrane by numerous points of interrupted suture.

But if the tumour be at once extensive and deep, mere removal is not sufficient, but some provision must be made for supplying the blank left by the operation.

Fig. xx. 101

In cases where a third, or even a half, of the lower lip has thus been removed, it may be found sufficient freely to dissect what is left of the lip from the gums, and thus approximate the cut surfaces in the middle line.

This alone, however, would so much diminish the buccal orifice, and twist its corners, as to cause great deformity. The addition of an incision horizontally outwards, at one or both angles of the mouth, will do away with such risk, and allow the surfaces to come together without puckering; while by stitching the skin and mucous membrane together in the course of these horizontal incisions, we can increase the size of the buccal orifice almost ad libitum.

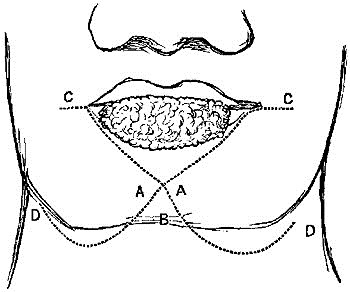

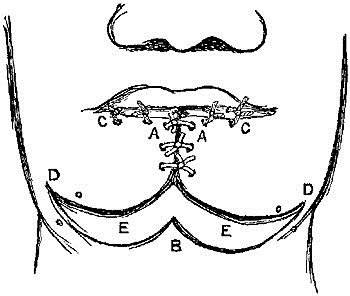

Lastly, when the lower lip has been entirely removed, it is still possible to supply its place in the following manner, which was devised by Mr. Syme: The tumour being fairly isolated by a V-shaped incision (Fig. xxi.) C A C including the whole thickness of the lip, each of the incisions should be prolonged downwards and outwards, as shown by the dotted lines A D, A D. The flaps thus marked out must be separated from the bone, brought upwards, and approximated in the middle line. Possibly it may be necessary still further to enlarge the buccal orifice by short lateral incisions, C C. Whether these are required or not, silk stitches are to be introduced to unite the skin and mucous membrane along the lines a c. The gap left between D B D must be left to granulate, but in most cases may be very much diminished in size by additional sutures at its outer corners, near d. The granulating surface E E very rapidly heals up, leaving a dimple on each side, which rather improves the appearance, by adding to the prominence of the chin, b.

Fig. xxi. 102

Fig. xxii. 103

The Operations for Harelip, though all conducted on the same general principles, vary considerably in extent required according to the position and size of the fissure or fissures to be remedied.

1. For Single Harelip.—Where the fissure extends only from the prolabium up to the attachment of the lip to the gums: this is very easily remedied, the chief risk being lest the surgeon should not remove enough of the edges of the fissure.

Operation.—Bleeding being controlled by an assistant, the surgeon fixes a pair of spring artery forceps into the mucous membrane and skin at the salient angle at each side of the fissure. Taking one of these in his left hand, he puts the edge to be pared on the stretch, and then with a sharp narrow straight bistoury he transfixes the lip at the point just beyond the upper angle of the fissure, and cuts outwards, being careful to remove the whole thinner part of the lip, and to leave the edge rather concave than convex. If left convex, or even quite straight, there is a risk that, after union has taken place, an angle remain showing the position of the cleft. The same is then to be done on the other side. The bleeding is then to be controlled by twisting the larger vessels, and if oozing still continues from the smaller ones, a pad of lint should be placed in the wound, and a few minutes' delay given, as, to facilitate immediate union, it is of the greatest importance that all hæmorrhage should have ceased before the edges are brought together.

When the bleeding has ceased, the edges should be approximated by two or more points of interrupted metallic suture inserted very deeply through the tissues, and taking a good hold of the edges of the wound. If the edges do not fit accurately, one or two horse-hair sutures will help. Some surgeons still prefer the old harelip needles secured by a figure-of-eight suture. A silk suture inserted through the prolabium is of great advantage, as it keeps the inner surface of the wound closed, which without it is very apt to be kept open by the pressure of the teeth or gums, and in infants by the movements of the tip of the tongue.

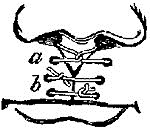

Various methods have been devised to utilise, if possible, the portion of the edge of the lip which is separated during the operation of refreshing the edges, for the purpose of filling up the sort of cleft or gap which is apt to be noticed at the edge of the prolabium. The most ingenious and simplest of these is that proposed by M. Nelaton, for use in cases where the fissure does not extend so far up as the nose. It consists in leaving the two portions which are pared off (Fig. xxiii.) the sides of the cleft attached to each other as well as to the free edge of the lip, then pulling them down, so as to bring their bleeding surfaces into apposition, and make a diamond-shaped wound instead of a triangular cleft (Fig. xxiv.) When brought together by sutures a projection is left at the edge of the lip; this, in most cases, disappears; if it does not, it can easily be pared down.

Fig. xxiii. 104

Fig. xxiv. 105

2. When the fissure, though single, extends upwards into the nose, the operation is more difficult, and the result frequently less satisfactory. The first thing to be done is to separate the lips from the gums, so as to make them more freely mobile. The whole edges of the cleft require refreshing.

3. Double Harelip, without bony deformity, and where the intervening portion of the skin is vertical, does not project, and can be made useful for the new lip. Such cases are not very common, but when they do occur the question arises, How are they to be managed—in two separate operations or at once? I believe, in every case, at once. The central wedge-shaped portion is not large enough to extend downwards as far as the prolabium, but still should not be removed altogether, as it may be of great use, especially in bearing the columna nasi, and allowing its full development. The edges should be pared in the same way, and to the same extent as in single harelip, with the addition that the intervening portion should have its edges completely removed, and be left in the form of a wedge, with its apex downwards. The highest suture should be passed through first one side, then the base of the wedge, and then the other side; the second one through both, and the apex of the wedge; and a third should unite the prolabium, not including the wedge.

Fig. xxv. 106