полная версия

полная версияA Manual of the Operations of Surgery

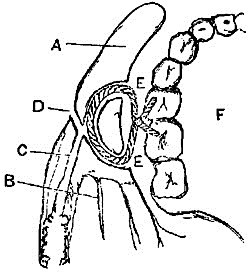

4. Double Harelip combined with fissures of the hard palate, and projection of a central bone. This is the analogue of the inter-maxillary bone in the lower animals, and bears the two middle incisor teeth, and projects very variously in different cases. In some it projects horizontally forwards in the most hideous manner, in others it lies at an angle more or less oblique; in very few does it maintain its proper position; when projecting forwards, and as the teeth also share in its projection, it entirely prevents approximation of the edges of the fissures by operation, so it must first be dealt with in one of two ways, either—

Fig. xxvi. 107

(1.) It may be at once removed with bone-pliers, the piece of skin over it being saved. This is the best that can be done in cases of old standing after the first year or two, though attempts have been made to break the neck of the projecting portion, and thus permit of its being shoved back.

(2.) By gradual pressure by a spring truss, strapping, or a bandage, it may be forced back. This is possible only in cases where the deformity has been comparatively slight, and the patient has been seen early. The edges must then be pared and approximated as directed above.

One or two points about the operation for harelip require a special notice:—

1. When to operate.—Great differences in opinion exist. Some say not before two or three years, others within two or three days, or even hours, after birth.

Probably the safest time is not much earlier than the second month in very strong children, the fifth in weakly ones, up to the commencement of the first dentition; and when once dentition has commenced it is not so safe to operate till it is over.

Prior to dentition the operation is attended with rather more risk, but again, if delayed, there is great risk that the teeth do not come in properly.

2. With regard to the most delicate part of the operation, the management of the prolabium.—Some are satisfied, and I believe rightly, with careful apposition by a silk suture after a sufficient amount of the edges has been removed; others have proposed various plans to obviate any risk of an angle remaining.

Malgaigne proposes to retain a small portion of the parings of the edge to make small flap at each side; Lloyd a single one from the long half of the lip, and brings it up under the opposite one, securing it with a stitch.

CHAPTER VII.

OPERATIONS ON THE JAWS

1. Excision of the Upper Jaw.—With regard to the morbid conditions for which this operation is undertaken, it may be sufficient here to observe, that in no case can the operation be called justifiable in which the disease extends beyond the upper jaw-bone and the corresponding palate-bone, for unless the morbid growth be entirely removed, recurrence is inevitable, and no advantage is gained by the operation. It is undertaken for the removal of tumours of the antrum and of the alveolar margins, in all which cases the section for its removal must be made through healthy bone, and wide of the disease, so as to insure that the whole is removed. There are other cases in which the whole or part of the upper jaw has been removed for the purpose of giving access to disease behind, for example, to naso-pharyngeal polypi with extensive attachments.

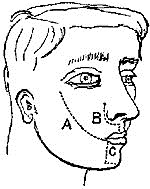

In describing the operation for the excision of the entire upper jaw, we have to consider—(1.) what incisions through the soft parts will expose the tumour best, and with least deformity; (2.) what bony processes require to be divided, and where. Very various incisions have been recommended by various authors; some describing three, in various directions, forming flaps of different sizes, while others, again, are satisfied with a very small division of the upper lip into the nose, or even attempt removal of the bone without any incision through the skin at all. These discrepancies depend in great measure on different views of what constitutes excision of the upper jaw, the more complicated ones contemplating removal of the whole bone anatomically so called, including the floor of the orbit, while the less complicated ones are suitable for cases in which a much less extensive removal is required.

To remove the whole bone, an incision (Fig. xxvii. A) of the skin must extend from the angle of the mouth upwards and outwards in a slightly curved direction with its convexity downwards, as far on the malar bone as half an inch outside of the outer angle of the eye. The flaps must then be raised in both directions, the inner one specially dissected off the bones, so as to expose thoroughly the nasal cavity. It is of great importance thoroughly to display the floor of the orbit, so that the attachment of the orbital fascia may be accurately cut through, the inferior oblique muscle divided at its origin, and the eye and the fat of the orbit cautiously raised from its floor.

Fig. xxvii. 108

Three processes of bone then require attention and division.

(1.) The articulation with the opposite bone in the hard palate. To divide this, one incisor tooth at least must be drawn, the soft palate divided by a knife to prevent laceration, and the thick alveolar portion sawn through in a longitudinal direction from before backwards.

(2.) The articulation with the malar bone at the upper angle of the incision through the skin. This must be notched with a small saw in a direction corresponding to the articulation, and then wrenched asunder by a pair of strong bone-pliers.

(3.) The nasal process of the upper jaw must now be divided by the pliers, one limb of which is cautiously inserted into the orbit, the other into the nose. If the disease extends high up in this process, it may be necessary partially to separate the corresponding nasal bone, and thus reach the suture between the nasal process and the frontal bone. The pliers must now be inserted into the groove already made by the saw on the hard palate, and the separation continued to the full extent backwards. A comparatively slight force exerted on the tumour either by the hand, or (when the tumour is small) by a pair of strong claw forceps, will suffice to break down the posterior attachments of the bone and remove it entire. The necessary laceration of the soft parts behind is so far an advantage, as it lessens the risk of hæmorrhage from the posterior palatine vessels.

The hæmorrhage from this operation was at one time much dreaded, but is rarely excessive; very few vessels require ligature, except those divided in the early stages in making the skin flaps; the hollow left should be stuffed with lint, which may be soaked in the perchloride of iron should there be any oozing.

The incisions recommended for this operation have been very various, and a knowledge of some of them may occasionally be useful, on account of specialities in the shape and size of the tumour. Liston "entered the bistoury over the external angular process of the frontal bone, and carried it down through the cheek to the corner of the mouth. Then the knife is to be pushed through the integument to the nasal process of the maxilla, the cartilage of the ala is detached from the bone, and lip cut through in the mesial line; the flap thus formed is to be dissected up and the bones divided."109 Dieffenbach made an incision through the upper lip and along the back or prominent part of the nose, up towards the inner canthus, from whence he carried the knife along the lower eyelid, at a right angle to the first incision as far as the malar bone.

In cases where the tumour is of moderate size, Sir W. Fergusson found110 it sufficient to divide the upper lip by a single incision exactly in the middle line, this incision to be continued into one or both nostrils, if required. The ala of the nose is so easily raised, and the tip so moveable as to give great facilities to the operator for clearing the bone even to the floor of the orbit.

In cases where the tumour is larger, or the bones more extensively affected, Sir W. Fergusson preferred an extension of the foregoing incision (Fig. xxvii. B) upwards along the edge of the nose almost to the angle of the eye, and thence at a right angle along the lower eyelid, as far as may be necessary, even to the zygoma. The advantages claimed for such procedures are that the deformity is less and the vessels are divided at their terminal extremities.

2. Excision of the Lower Jaw.—Removal of portions, greater or smaller, of the lower jaw, for tumours, simple or malignant, are now operations of very frequent occurrence, while in some few cases the whole bone has been removed at both its articulations.

The operative procedures vary much, according to the amount of bone requiring removal, and also the position of the portion to be excised.

(1.) Of a portion only of one side of the body of the bone.—This is perhaps the simplest form of operation, and is frequently required for tumours, specially for epulis.

Incision.—If the parts are tolerably lax and the tumour small, a single incision just at the lower edge of the bone, of a length rather greater than the piece of bone to be removed, will suffice; this will divide the facial artery, which must be tied or compressed,111 while the surgeon, dissecting on the tumour, separates the flaps in front, cutting upwards into the mouth, and then detaches the mylohyoid below, and clears the bone freely from mucous membrane. He then, with a narrow saw, notches the bone beyond the tumour at each side, and, introducing strong bone-pliers into the notches, is enabled to separate the required portion. The wound is then stitched up, and a very rapid cure generally results with very little deformity, as the cicatrix is in shadow. If from the size of the tumour more room is needed, it can easily be got by an additional incision from the angle of the mouth joining the former.

To prevent deformity, which is apt to result from the centre of the chin crossing the middle line, it is often a wise precaution to have a silver plate prepared fitting the molar teeth of both jaws on the sound side, and thus acting as a splint. Such a precaution may be required in any operation in which the lower jaw is sawn through.

N.B.—There are certain cases in which the epulis is small and confined to the alveolar margin, in which an attempt may be made to retain the base of the jaw entire, and remove the tumour without any incision of the skin. The mucous membrane on both sides being carefully dissected from the affected part, the bone may be sawn as before, but only through the alveolar portion, the groves of the saw converging as they penetrate, then by a pair of strong curved bone-pliers, the affected alveolar portion is to be scooped out without injuring the base. This proceeding, which has been practised by Syme, Fergusson, Pollock, the author in many cases, and others, leaves no deformity, but, it must be owned, is much more liable to the risk of recurrence of the disease, and for this reason is strongly condemned by Gross.

Note.—In this, as in all other operations on the jaws, the very first thing to be done is to draw the teeth at the spots at which the saw is to be applied.

(2.) Excision of a portion involving the Symphysis.—Free access is of importance. The best incision is probably one which (Fig. xxvii. C) commences at the angle of the mouth opposite the healthy portion of jaw, extends down to the place at which the saw is to be applied and then along the base of the jaw past the middle line to the other point of section. The flap is to be thrown up and the bone cleared. The next point to be noticed is, that when, in clearing the bone behind, the muscles attached to the symphysis are divided, the tongue loses its support, and unless watched may tend to fall backwards, embarrassing respiration and even perhaps choking the patient. The tongue, being confided to a special assistant, must be drawn well forwards. Various plans have been devised for keeping it in position, as stitching it to the point of the patient's nose; putting a ligature into its apex, and fastening it to the cheek by a piece of strapping, and transfixing its roots with a harelip needle, used to stitch up a central incision in the chin. The tendency to retraction very soon ceases, new attachments are formed by the muscles, and after the first five or six days there is very little risk of the tongue giving rise to any untoward consequences by its displacement.

(3.) Disarticulation of one, or both Joints.—When the portion of bone implicated involves disarticulation for its complete removal, the difficulty of the operation is much increased. The remarkably strong attachments of the joint, especially the relation of the temporal muscle to the coronoid process, and the close proximity of large arteries and nerves, especially the internal maxillary artery and the lingual nerve, render this disarticulation very difficult.

The chief points to be attended to seem to be (1.) that the incision through the skin should extend quite up to the level of the articulation; (2.) that the bone should be sawn through at the other side of the tumour, and freely cleared from all its attachments, before any attempt be made at disarticulation, for by means of the tumour great leverage can be attained, so as to put the muscles on the stretch, and allow them to be safely divided; (3.) that the articulation should always be entered from the front, not from behind, and the inner side of the condyle should be very carefully cleaned, the surgeon cutting on the bone so as to avoid, if possible, the internal maxillary artery; (4.) free and early division of the attachment of the temporal muscle to the coronoid process.

Disarticulation of the entire bone has been very rarely performed.112 If necessary, it can be performed without any incision into the mouth, by one semilunar sweep from one articulation to the other, passing along the lower margin of each side of the body, and just below the symphysis of the chin.

Disarticulation of the Ramus without opening into the cavity of the Mouth.—That this operation is possible, though it may not be often required, is shown by the following case by Mr. Syme. It was a tumour of the ramus, extending only as far forwards as the wisdom-tooth:—

"An incision was made from the zygomatic arch down along the posterior margin of the ramus, slightly curved with its convexity towards the ear, to a little way beyond the base of the jaw. The parotid gland and masseter muscle being dissected off the jaw, it was divided by cutting-pliers immediately behind the wisdom-tooth, after being notched with a saw. The ramus was then seized by a strong pair of tooth-forceps, and notwithstanding strong posterior attachments, was drawn outwards, its muscular connections divided and turned out entire. There was thus no wound of the mucous membrane of the mouth, the masseter and pterygoid muscles were not completely divided, and the facial artery was intact."113

Fergusson114 holds that even the very largest tumours of the lower jaw may be successfully removed without opening into the orifice of the mouth at all by division of the lips. A large lunated incision below the lower margin of the bone, with its ends extending upwards to within half an inch of the lips, will give free access, and yet avoid both hæmorrhage and deformity, as the labial artery and vein are not cut, and there is no trouble in readjusting the lips. Some tumours of lower jaw can be removed without any wound of skin.

CHAPTER VIII.

OPERATIONS ON MOUTH AND THROAT

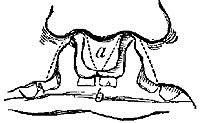

Salivary Fistula, Operation for.—After a wound or abscess of the cheek, in which the parotid duct is implicated, a salivary fistula is very apt to remain. The saliva thus discharges in the cheek, giving rise to considerable annoyance, as well as injury to the digestion. It is by no means easy to cure this. Perhaps the best operation is the one of which a rude diagram is given (Fig. xxviii.). The duct (c) communicates with the fistula (d). One end of a thread, either silken or metallic, should be passed through the fistula, and then as far backwards as convenient through the cheek into the mouth; the needle should then be withdrawn, the thread being left in. The other end being threaded should then be re-inserted at the fistula, and carried forwards in a similar manner; the needle should be again unthreaded in the mouth and withdrawn; the two ends should then be tied pretty tightly inside, and allowed to make their way by ulceration into the cavity of the mouth. A passage will thus be obtained for the saliva into the mouth, and every possible precaution should be taken to enable the external wound to close.

Fig. xxviii. 115

Excision of the Tongue, for malignant disease of the organ, may be either complete or partial. Complete excision affords a hope of permanent and complete relief from the disease, but it is an operation of extreme difficulty and danger. It may be performed in either of the following methods. The first is the only one in which absolute completeness of removal is insured.

1. Syme's method of excision.—The patient being seated on a chair, chloroform was not administered, so that the blood might escape forwards, and not pass into the pharynx. The operation is thus described:116—

"Having extracted one of the front incisors, I cut through the middle of the lip and continued the incision down to the os hyoides, then sawed through the jaw in the same line, and insinuating my finger under the tongue as a guide to the knife, divided the mucous lining of the mouth, together with the attachment of the genio-hyoglossi. While the two halves of the bone were held apart, I dissected backwards, and cut through the hyoglossi, along with the mucous membrane covering them, so as to allow the tongue to be pulled forward, and bring into view the situation of the lingual arteries, which were cut and tied, first on one side, and then on the other. The process might now have been at once completed, had I not feared that the epiglottis might be implicated in the disease, which extended beyond the reach of my finger, and thus suffer injury from the knife if used without a guide. I therefore cut away about two-thirds of the tongue, and then being able to reach the os hyoides with my finger, retained it there while the remaining attachments were divided by the knife in my other hand close to the bone. Some small arterial branches having been tied, the edges of the wound were brought together and retained by silver sutures, except at the lowest part, where the ligatures were allowed to maintain a drain for the discharge of fluids from the cavity." The patient was able to swallow from a drinking-cup with a spout on the day following the operation, and was able to travel upwards of 200 miles within four weeks of the operation.

2. By the Écraseur.—Nunneley of Leeds has recorded cases in which he made a small incision through the skin, and mylohyoid and geniohyoid muscles, and through this passed a curved needle bearing the chain of the écraseur completely round the base of the tongue. In one case the chain was unsatisfactory, but strong whipcord was introduced as it was withdrawn, and tied with all possible force. The organ eventually sloughed away, with a cure which lasted at least for some months.

Sir James Paget operates as follows:—

The patient is placed under the influence of chloroform, and the mouth held widely open. The tongue is then drawn forwards, the mucous membrane and soft parts of the floor of the mouth, including the attachment of the genio-hyoglossi to the symphysis being divided close to the bone. The steel wire of an écraseur is then passed round its root as low down as possible, slowly tightened, and the tongue thus divided through its whole thickness in a very few minutes. The bleeding is slight, being almost entirely from the parts cut with the knife. Recovery has been rapid in the recorded cases.117

To Dr. George Buchanan of Glasgow the credit is due of the invention of the operation of removal of the half of the tongue in the median line. In at least one instance the cure after five years is still permanent.

Partial excisions of the tongue are as unsatisfactory in their results as they are unsound in principle, yet many cases present themselves, in which, while the patient urges some operative measure for his relief, the tumour is so limited as not to warrant the exceedingly dangerous operation of complete excision.

Portions may be removed in various ways:—

1. By the knife. If in the apex, by a V-shaped incision; if in the lateral regions, by a bold free incision with a probe-pointed bistoury round the tumour.

2. By ligature, drawn as tightly as possible, and, if the portion included be large, in successive portions.

3. By the écraseur.

Mr. Furneaux Jordan has removed the whole tongue with success by means of two écraseurs worked at the same time.118

4. By the galvano-caustic wire.

5. The author has in nine cases removed the affected half of the tongue by means of the thermo-cautery, first splitting it in the middle line and then cutting through the base with a curved platinum knife at a low red heat. In one only was there any trouble from hæmorrhage, and all made good recoveries.

Mr. Barwell has recorded (Lancet, 1879, vol. i.) an easy, safe, and comparatively painless mode of removing the tongue by écraseurs.

Mr. Walter Whitehead,119 of Manchester, has had a very large experience of an operation devised by himself, in which, after pulling the tongue well forward by a string previously introduced near its apex, and the mouth being held open by a gag, he detaches the organ from jaw and fauces by successive short snips with scissors, and then in same manner divides the muscles, tying or twisting the vessels as they bleed. His success has been very great by this method, though others who have tried it have sometimes found bleeding troublesome.

It is comparatively seldom now necessary to split the jaw and perform Syme's operation, and in all operations on the tongue the thermocautory (Paquelin's) is of great use.

Regnoli's method120 may deserve a brief notice. A semilunar incision along the base of the jaw, from one angle to the other, detaches the muscles and soft structures, and is thrown down; the tongue is then drawn through the opening, and can be freely dealt with either by knife or ligature. After removal the flap is replaced.

Fissures in the Palate.—The operations requisite for the cure of fissures in the soft and hard palates are so complicated in their details, that a small treatise would be required thoroughly to describe the various procedures.

Different cases vary so much in the nature and amount of their deformity, that at least five different sets of cases have been described. It is sufficient here merely to describe the absolutely essential principles of the operations for the cure of fissures of the hard and soft palate respectively.

In all operations on the palate, two conditions used to be considered requisite for success:—1. That the patient should have arrived at years of discretion, at twelve or fourteen years at least; that he be possessed of considerable firmness, and be extremely anxious for a cure, so as to give full and intelligent co-operation. 2. That for some days or weeks prior to the operation the mouth and palate should have been trained to open widely and to bear manipulation, without reflex action being excited. Professor Billroth of Vienna,121 and Mr. Thomas Smith122 of London, have had cases which prove the possibility of performing this operation in childhood, under chloroform, with the assistance, in the English cases, of a suitable gag, invented by Mr. Smith. The effect of the operation on the voice of the child has been very encouraging, as much more improvement takes place than in cases where the operation is performed late in life.

Fissure in the soft palate only appears as a triangular cleft, the apex of which is above, the base being a line between the points of the bifid uvula, which are widely separated. To cure this it is required—