полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

I have never seen this animal in the flesh, and can only therefore give what I gather from others about it, which is not much, as it is not very well known.

SIZE.—Stands nearly four feet at the shoulder.

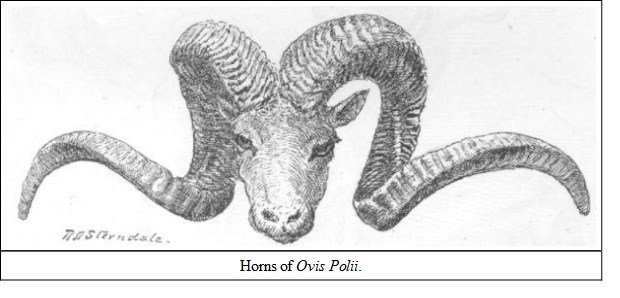

In the article on Asiatic sheep by Sir Victor Brooke and Mr. B. Brooke in the 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society' in 1875, there is an excellent series of engravings of horns of these animals, amongst which are two of Ovis Polii. The description of the animal itself appears to be faulty, for it is stated that around the neck is a pure white mane, whereas Mr. Blanford wrote to the Society a few months later to the effect that he had examined a series of skins brought from Kashgar, and found that none possess a trace of a mane along the neck, as represented in a plate of the animal, there being some long hair behind the horns and a little between the shoulders, but none on the back of the neck. The animal has a very short tail also—so short it can hardly be seen in life. According to M. Severtzoff there is a dark line above the spinal column from the shoulders to the loins; a white anal disc surrounds the tail; this disc above is bordered by a rather dark line, but below it extends largely over the hinder parts of the thighs, shading gradually into the brown colour of the legs. The light greyish-brown of the sides shades off into white towards the belly.

He gives the following particulars concerning its habits: "It is not a regular inhabitant of the mountains, but of high situated hilly plains, where Festuca, Artemisia, and even Salsolæ form its principal food. It only takes to the mountains for purposes of concealment, avoiding even then the more rocky localities. It keeps to the same localities summer and winter. Its speed is very great, but the difficulty in overtaking wounded specimens may be partly attributed to the distressing effect of the rarefied air upon the horses, which has apparently no effect whatever on the sheep. The weight of an old specimen killed and gralloched by M. Severtzoff was too much for a strong mountain camel, the animal requiring four hours to do four versts (2·6 miles), and being obliged to lie down several times during the journey. He reckons the entire weight of a male Ovis Polii to be not less than 16 or 17 poods (576 to 612 lbs.); the head and horns alone weigh over two poods (72 lbs.)."33

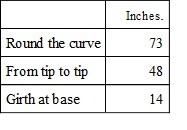

I have before me a beautiful photograph by Mr. Oscar Malitte, of Dehra Doon, of a very large skull of this sheep, with the measurements given. The photograph is an excellent one of a magnificent head, and I should say if the measurements have been correctly made, that the horns are the longest, though not the thickest, on record.

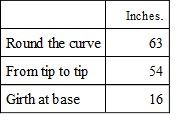

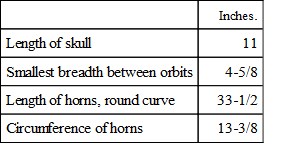

The dimensions given are as follows:—

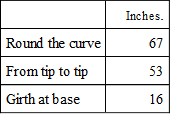

The next largest head to this is the very fine one in the Indian Museum, presented by Major Biddulph:—

There is another in the British Museum:—

From the above measurements it will be seen that the horns in the photograph before me are of greater length, but not so massive as the other two. They are also more compressed in their curvature than the others, and so the tip to tip measurement is less. The skull appears to be that of a very old animal; the horns are quite joined at the base, and from the incrustation on the bones I should say it had been picked up, and was not a shikar trophy. Anyhow it is a valuable specimen.34

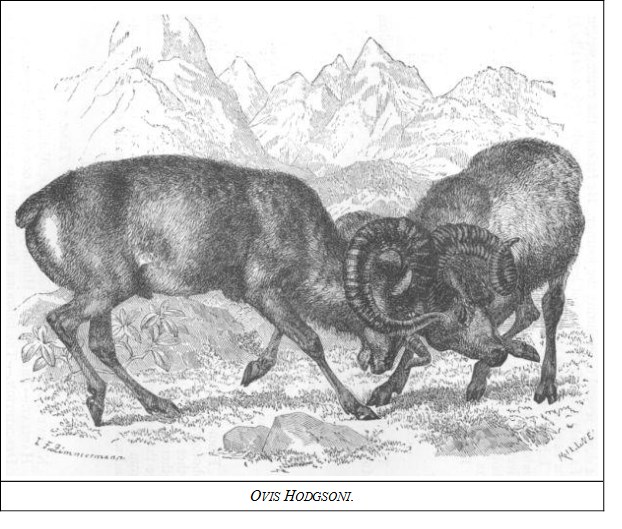

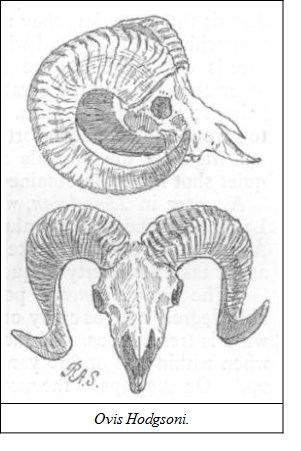

NO. 439. OVIS HODGSONIThe Argali or Ovis Ammon of ThibetNATIVE NAMES.—Hyan, Nuan, Nyan, Niar, Nyaud or Gnow.

HABITAT.—The Thibetan Himalayas at 15,000 feet and upwards.

DESCRIPTION.—The following description was given by a correspondent of the Civil and Military Gazette in the issue of the 21st October, 1880: "The male dark earthy brown above, lighter below; rump lighter coloured; tail one inch; white ruff of long hairs on throat and chin; hair of body short, brittle, and close-set. The female darker coloured than the male, and may often be distinguished, when too far to see the horns, by the dark hue of the neck." Both male and female are horned; the horns of the former are very large, some are reported as being as much as four feet long, and 22 inches in circumference at the base. Dr. Jerdon quotes Colonel Markham in giving 24 inches as the circumference of one pair. They are deeply rugose, triangular, and compressed, deeper than broad at the base, forming a bold sweep of about four-fifths of a circle, the points turning outwards, and ending obtusely. The horns of the female are mentioned by various writers as being from 18 to 22 inches, slightly curved; but the correspondent of the Civil and Military Gazette above quoted gives 24 inches as his experience.

SIZE.—From 10 to 12 hands, sometimes an inch over.

A very interesting account of this animal, with a good photograph of the head, is given in Kinloch's 'Large Game-shooting in Thibet and the North-west.' He says: "In winter the Ovis Ammon inhabits the lower and more sheltered valleys, where the snow does not lie in any great quantity. As summer advances, the males separate from the females, and betake themselves to higher and more secluded places. They appear to be particular in their choice of a locality, repairing year after year to the same places, where they may always be found, and entirely neglecting other hills which apparently possess equal advantages as regards pasturage and water. Without a knowledge of their haunts a sportsman might wander for days and never meet with old rams, although perhaps never very far from them. I have myself experienced this, having hunted for days over likely ground without seeing even the track of a ram, and afterwards, under the guidance of an intelligent Tartar, found plenty of them on exactly similar ground a mile or two from where I had been. The flesh of the Ovis Ammon, like that of all the Thibetan ruminants, is excellent; it is always tender, even on the day it is killed, and of very good flavour, possibly caused by the aromatic herbs which constitute so large a portion of the scanty vegetation of those arid regions.

"No animal is more wary than the Ovis Ammon, and this, combined with the open nature of the ground which it usually inhabits, renders it perhaps the most difficult of all beasts to approach. It is however, of course, sometimes found on ground where it can be stalked, but even then it is most difficult to obtain a quiet shot, as the instant one's head is raised one of the herd is nearly sure to give the alarm, and one only gets a running shot.

"Ovis Ammon shooting requires a great deal of patience. In the first place, unless the sportsman has very good information regarding the ground, he may wander for days before he discovers the haunts of the old rams; and, secondly, he may find them on ground where it is hopeless to approach them. In the latter case all that can be done is to wait, watch them until they move to better ground, and if they will not do this the same day, they must be left till the next. Sooner or later they will move to ground where they can be stalked, and then, if proper care is exercised, they are not much more difficult to get near than other animals; but the greatest precautions must be taken to prevent being seen before one fires. Some men may think this sort of shooting too troublesome, and resort to driving, but this is very uncertain work, and frightens the animals away, when, by the exercise of patience, a quiet shot might be obtained."

A writer in The Asian, whose 'Sportsman's Guide to Kashmir and Ladakh' contains most valuable information, writes thus in the issue of August 30, 1881, of the keen sense of smell possessed by this animal, and I take the liberty of quoting a paragraph:—

"The Ovis Ammon is possessed of the sense of smell to a remarkable degree, and, as every one who has stalked in Ladakh is aware, the wind is treacherous. If the stalker feels a puff of wind on his back when within 700 or 800 yards of the game, he well knows that it is 'all up.' On the tops of the mountains and in the vicinity of glaciers these puffs of wind are of frequent occurrence; often they will only last for a few seconds, but that is sufficiently long to ruin the chance of getting a shot at the Ovis. Except for this one fact, we cannot admit that the nyan is harder to approach than any other hill sheep."

NO. 440. OVIS KARELINIKarelin's Wild SheepNATIVE NAMES.—Ar or Ghúljar (male), Arka (female), Khirghiz; Kúlja, Turki of Kashgar.

HABITAT.—Mountains north-west of Kashgar, and thence northwards beyond the Thian Shan mountains on to the Semiretchinsk Altai.

DESCRIPTION (by Sir Victor Brooke and Mr. Brooke, translated and abstracted from Severtzoff, see 'P. Z. S.' 1875, p. 512).—"The horns are moderately thick, with rather rounded edges; frontal surface very prominent, orbital surface rather flat, narrowing only in the last third of its length. The horns are three times as long as the skull. The basal and terminal axis of the horns rise parallel with each other; the median axis parallel with the axis of the skull. The neck is covered by a white mane, shaded with greyish-brown. The light brown of the back and sides is separated from the yellowish-white of the belly by a wide dark line. The light brown of the upper parts gets gradually lighter towards the tail, where it becomes greyish-white, but does not form a sharply marked anal disc. On the back there is a sharply marked dark line running from the shoulders to the loins. I did not find any soft hair under the long winter hair in October."

SIZE.—Height at the shoulder, 3 feet 6 inches; length of the horns, from 44 to 45 inches.

The following is a description by Dr. Stoliczka of this animal, which he took to be Ovis Polii, and described it as such, in the 'P. Z. S.' for 1874, page 425. In the same volume is a plate which, however, is shewn by Mr. Blanford ('Sc. Res. Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 83) to be inaccurate:—

"Male in winter dress.—General colour above hoary brown, distinctly rufescent or fawn on the upper hind neck and above the shoulders, darker on the loins, with a dark line extending along the ridge of tail to the tip. Head above and at the sides a greyish-brown, darkest on the hind head, where the central hairs are from four to five inches long, while between the shoulders somewhat elongated hairs indicate a short mane. Middle of upper neck hoary white, generally tinged with fawn; sides of body and the upper part of the limbs shading from brown to white, the hair becoming more and more tipped with the latter colour. Face, all the lower parts, limbs, tail, and all the hinder parts, extending well above towards the loins, pure white.

"The hairs on the lower neck are very much lengthened, being from five to six inches long. Ears hoary brown externally, almost white internally. Pits in front of the eye distinct, of moderate size and depth, and the hair round them generally somewhat darker brown than the rest of sides of the head. The nose is slightly arched and the muzzle sloping. The hair is strong, wiry, and very thickly set, and at the base intermixed with scanty, very fine fleece; the average length of the hairs on the back is 2 to 2½ inches. The iris is brown. The horns are subtriangular, touching each other at the base, curving gradually with a long sweep backwards and outwards; and, after completing a full circle, the compressed points again curve backwards and outwards; their surface is more or less closely transversely ridged.

"The colour of full-grown females does not differ essentially from that of the males, except that the former have much less white on the middle of the upper neck. The snout is sometimes brown, sometimes almost entirely white, the dark eye-pits becoming then particularly conspicuous. The dark ridge along the tail is also scarcely traceable. In size, both sexes of Ovis Polii appear to be very nearly equal, but the head of the female is less massive, and the horns, as in allied species, are comparatively small: the length of horn of one of the largest females obtained is 14 inches along the periphery, the distance at the tips being 15 inches, and at the base a little more than one inch. The horns themselves are much compressed; the upper anterior ridge is wanting on them; they curve gradually backwards and outwards towards the tip, though they do not nearly complete even a semicircle. In young males, the horns at first resemble in direction and slight curvature those of the female, but they are always thicker at the base and distinctly triangular.

"The length of the biggest horn of male along the periphery of curve was 56 inches, and the greatest circumference of a horn of a male specimen at the base 18½ inches.

"Mr. Blyth, the original describer of Ovis Polii, from its horns, was justified in expecting, from their enormous size, a correspondingly large-bodied animal; but in reality such does not appear to exist. Although the distance between the tips of the horns seems to be generally about equal to the length of the body, and although the horns are very much larger, but not thicker or equally massive, with those of the Ovis Ammon of the Himalayas, the body of the latter seems to be comparatively higher. Still it is possible that the Ovis Polii of the Pamir may stand higher than the specimens described, which were obtained from the Tian Shan range.

"Large flocks of Ovis Polii were observed on the undulating high plateau to the south of the Chadow-Kul, where grass vegetation is abundant. At the time the officers of the Mission visited this ground, i.e. in the beginning of January, it was the rutting season. The characters of the ground upon the Pamir and upon the part of the Tian Shan inhabited by these wild sheep are exactly similar."

The following remarks on the habits of this species are from Sir Victor Brooke's abstract of Servertzoft's description: "Ovis Karelini, like other sheep, does not live exclusively amongst the rocks, as is the case with the different species of Capra. It is not satisfied, like the latter, with small tufts of grass growing in the clefts of the rocks, but requires more extensive feeding grounds; it is, therefore, more easily driven from certain districts than is the case with Capra. In the neighbourhood of Kopal, for instance, the goats are abundant in the central parts of the steppes of Kara, whilst the sheep have been partially driven from these places, only visiting them in autumn.

"On the southern ranges of the Semiretchinsk Altai, in the vicinity of the river Ili, wherever good meadows and rocky places are found, Ovis Karelini occurs at elevations of from 2000 to 3000 feet; at the sources of the rivers Lepsa, Sarkan, Kora, Karatala, and Koksa it goes as high as 10,000, and even to 12,000 feet in the neighbourhood of the Upper Narin. In winter it is found at much lower elevations."

In a paper by Captain H. Trotter, R.E., read before the Royal Geographical Society on the 13th of May, 1878, on the geographical results of the mission to Kashgar under Sir Douglas Forsyth ('Journal R. G. S.' vol. xlviii., 1878, p. 193), I find the following account refering to this sheep, there mentioned under the name of Ovis Polii: "For twenty-five miles above Chakmák the road continues gently ascending along the course of the frozen stream, passing through volcanic rocks to Turgat Bela, a little short of which the nature of the country alters, and the precipitous hills are replaced by gently undulating grassy slopes, abounding with the Ovis Polii.35

"These extensive grassy slopes, somewhat resembling the English downs, are a very curious feature of the country, and not only attract the Kirghiz as grazing grounds for their cattle, but are equally sought after by the large herds of guljar, in one of which Dr. Stoliczka counted no less than eighty-five."

The Chakmák and Turgat Bela spoken of are on the southern slopes of the Thian Shan mountains, which form the boundary between Russia and Eastern Turkestan, separating the provinces of Semiretchinsk and Kashghar. The Turgat pass, about 12,760 feet, lies between the Kashgharian fort of Chakmák and the Russian fort Naryn or Narin. Captain Trotter mentions in a foot-note that these sheep, as well as ibex, abound in these hills in such large quantities that they form the principal food of the garrisons of the outposts. At Chakmák they saw a large shed piled up to the roof with the frozen carcases of these animals. (A most valuable map of the country is published in the 'Journal' with this paper.)

The chief difference between this species and Ovis Polii consists in the much greater length and divergence of horns of the latter and the longer hair on the neck.

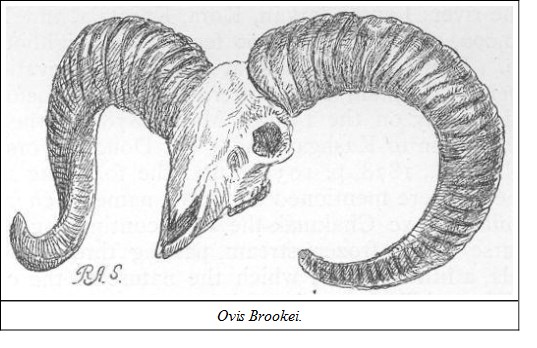

NO. 441. OVIS BROOKEIBrooke's Wild SheepHABITAT.—Ladakh, or probably the Kuenluen range north of Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—This species is founded on a single specimen, which, in the opinion of Mr. Blyth, Mr. Edwin Ward, F.Z.S., Sir Victor Brooke and others, differed materially from all other wild sheep, but, as they had only a head to go upon, further investigation in this direction is necessary. It is not even certain where the animal was shot, but it is believed to have been obtained in the vicinity of Leh in Ladakh. It is apparently allied to the O. Ammon of Thibet, which Sir Victor and Mr. B. Brooke term in their paper O. Hodgsonii, but it differs in its much smaller size, in its deeply sulcated horns, the angles of which are very much rounded, and the terminal curve but slightly developed. It differs also from O. Vignei and O. Karelini. The orbits project less, with greater width between them, the length of the molar teeth also exceeds the others. There are two wood-cuts of the skull and horns in the 'P. Z. S.' 1874, page 143, illustrating Mr. Edwin Ward's paper on the subject.

The following are the dimensions of the specimen:—

NATIVE NAMES.—Sha or Shapoo.

HABITAT.—Little Thibet; Ladakh, from 12,000 to 14,000 feet.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour brownish-grey, beneath paler; belly white; a short beard of stiffish brown hair; the horns of the male are sub-triangular, rather compressed laterally and rounded posteriorly, deeply sulcated, curving outward and backward from the skull; points divergent. The female is beardless, with small horns. The male horns run from 25 to 35 inches, but larger have been recorded.

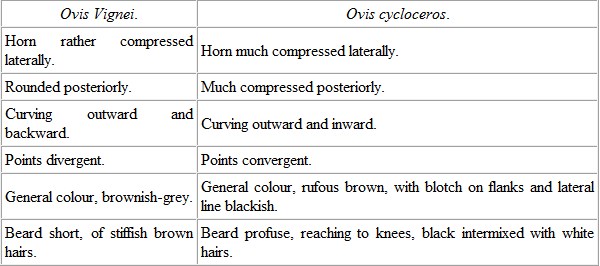

This sheep was for some time, and is still by some, confounded with the oorial (Ovis cycloceros), but there are distinct differences, as will be seen further on, when I sum up the evidence. It inhabits the elevated ranges of Ladakh, and is found in Baltistan, where it is called the oorin.

NO. 443. OVIS CYCLOCEROSThe Punjab Wild Sheep (Jerdon's No. 236)NATIVE NAMES.—Oorial or Ooria, in the Punjab; Koch or Kuch, in the Suleiman range.

HABITAT.—The Salt range of the Punjab; on the Suleiman range; the Hazarah hills; and the vicinity of Peshawar.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour rufous brown; face livid, side of mouth and chin white; a long thick black beard mixed with white hairs from throat to breast, reaching to the knees; legs below knees and feet white; belly white, a blotch on the flanks; outside of legs and a lateral line blackish. The horns of the male are sub-triangular, much compressed laterally and posteriorly; in fact one may say concave at the sides, that is, from the base of the horn to about one half; transversely sulcated; curving outwards, and returning inward towards the face; points convergent. The female is more uniform pale brown, with whitish belly; no beard, and short straight horns.

SIZE.—About 5 feet in length, and 3 feet high; horns from 25 to 30 inches round the curve.36 The marked distinctions between the two species may be thus briefly summed up:—

Mr. Sclater, with reference to the two in his paper on the Punjab Sheep living in the Zoological Society's Garden in 1860 ('P. Z. S.' 1860, page 126), says: "On comparing the skull (of O. cycloceros) with that of the shapoo we observe a general resemblance. But it may be noted that the sub-orbital pits in the present species are smaller, deeper, and more rounded; the nasal bones are considerably shorter and more pointed, and the series of molar teeth (formed in each skull of three premolars and three molars) measures only 2·85 instead of 3·20 inches in total length."

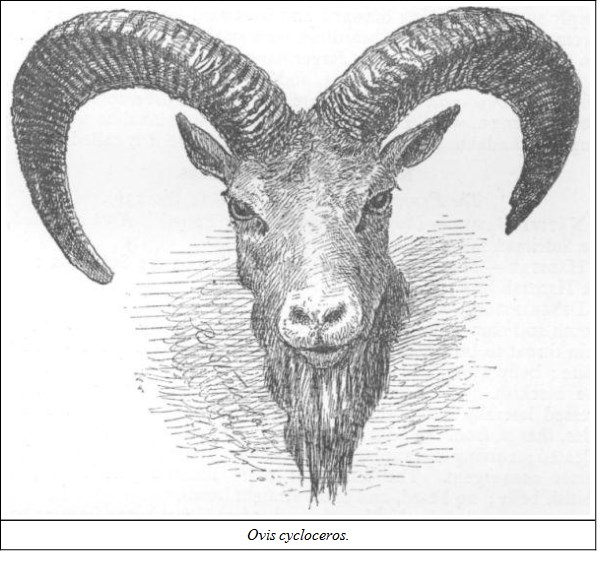

There is a fine coloured plate of this animal in that magnificent folio work—Wolf's 'Zoological Sketches,' showing the male, female, and lambs; and in that valuable book of Kinloch's, 'Large Game-shooting in Thibet and the North-west' is a very clear photograph of the oorial's head, from which I give the above sketch. He gives the following account of its habits: "The oorial is found among low stony hills and ravines, which are generally more or less covered with thin jungle, consisting principally of thorny bushes. During the heat of the day the oorial conceal themselves a good deal, retiring to the most secluded places, but often coming down to feed in the evening on the crops surrounding the villages. Where not much disturbed, they will stay all day in the neighbourhood of their feeding grounds, and allow sheep and cattle to feed amongst them without concern; but where they have been much fired at they usually go a long distance before settling themselves for the day. They are generally found on capital ground for stalking, the chief drawback being the stony nature of the hills, which renders it difficult to walk silently. When fired at, oorial usually go leisurely away, stopping to gaze every now and then, so that several shots may often be fired at one herd."

Dr. Leith Adams says regarding it, that it "frequents bleak and barren mountains, composed of low ranges intersected by ravines and dry river courses, where vegetation is scanty at all seasons, and goats and sheep are seldom driven to pasture. It is found in small herds, and, being fond of salt, is generally most abundant in the neighbourhood of salt mines. Shy and watchful, it is difficult to approach, and possesses in an eminent degree the senses of sight and smell. It is seldom seen in the day-time, being secreted among rocks, whence it issues at dusk to feed in the fields and valleys, returning to its retreat at daybreak.

"When suddenly alarmed the males gives a loud shrill whistle, like the ibex. This is an invariable signal for the departure of the herd, which keeps moving all the rest of the day until dusk. Their bleat is like that of the tame species; and the males fight in the same way, but the form of the body and infra-orbital pits simulate the deer, hence it is often called the 'deer-sheep.' It equals the deer in speed and activity. The female gestates seven months. The rutting season is in September."

According to Captain Hutton the flesh is good and well-flavoured, "while the horns are placed as trophies of success and proofs of skill upon tombs and temples."