полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Besides the exhaustion of men and ships, it must also be admitted that no blockade could be relied on certainly to check the exit of an enemy's fleet. Villeneuve escaped from Toulon, Missiessy from Rochefort. "I am here watching the French squadron in Rochefort," wrote Collingwood, "but feel that it is not practicable to prevent their sailing; and yet, if they should get by me, I should be exceedingly mortified.... The only thing that can prevent their sailing is the apprehension that they may get among us, as they cannot know exactly where we are."238

Nevertheless, the strain then was endured. The English fleets girdled the shores of France and Spain; losses were made good; ships were repaired; as one officer fell, or was worn out at his post, another took his place. The strict guard over Brest broke up the emperor's combinations; the watchfulness of Nelson, despite an unusual concurrence of difficulties, followed the Toulon fleet, from the moment of its starting, across the Atlantic and back to the shores of Europe. It was long before they came to blows, before strategy stepped aside and tactics completed the work at Trafalgar; but step by step and point by point the rugged but disciplined seamen, the rusty and battered but well-handled ships, blocked each move of their unpractised opponents. Disposed in force before each arsenal of the enemy, and linked together by chains of smaller vessels, they might fail now and again to check a raid, but they effectually stopped all grand combinations of the enemy's squadrons.

The ships of 1805 were essentially the same as those of 1780. There had doubtless been progress and improvement; but the changes were in degree, not in kind. Not only so, but the fleets of twenty years earlier, under Hawke and his fellows, had dared the winters of the Bay of Biscay. "There is not in Hawke's correspondence," says his biographer, "the slightest indication that he himself doubted for a moment that it was not only possible, but his duty, to keep the sea, even through the storms of winter, and that he should soon be able to 'make downright work of it.'"239 If it be urged that the condition of the French navy was better, the character and training of its officers higher, than in the days of Hawke and Nelson, the fact must be admitted; nevertheless, the admiralty could not long have been ignorant that the number of such officers was still so deficient as seriously to affect the quality of the deck service, and the lack of seamen so great as to necessitate filling up the complements with soldiers. As for the personnel of the Spanish navy, there is no reason to believe it better than fifteen years later, when Nelson, speaking of Spain giving certain ships to France, said, "I take it for granted not manned [by Spaniards], as that would be the readiest way to lose them again."

In truth, however, it is too evident to need much arguing, that the surest way for the weaker party to neutralize the enemy's ships was to watch them in their harbors and fight them if they started. The only serious objection to doing this, in Europe, was the violence of the weather off the coasts of France and Spain, especially during the long nights of winter. This brought with it not only risk of immediate disaster, which strong, well-managed ships would rarely undergo, but a continual strain which no skill could prevent, and which therefore called for a large reserve of ships to relieve those sent in for repairs, or to refresh the crews.

The problem would be greatly simplified if the blockading fleet could find a convenient anchorage on the flank of the route the enemy must take, as Nelson in 1804 and 1805 used Maddalena Bay in Sardinia when watching the Toulon fleet,—a step to which he was further forced by the exceptionally bad condition of many of his ships. So Sir James Saumarez in 1800 even used Douarnenez Bay, on the French coast, only five miles from Brest, to anchor the in-shore squadron of the blockading force in heavy weather. The positions at Plymouth and Torbay cannot be considered perfectly satisfactory from this point of view; not being, like Maddalena Bay, on the flank of the enemy's route, but like Sta. Lucia, rather to its rear. Nevertheless, Hawke proved that diligence and well-managed ships could overcome this disadvantage, as Rodney also afterward showed on his less tempestuous station.

In the use of the ships at its disposal, taking the war of 1778 as a whole, the English ministry kept their foreign detachments in America, and in the West and East Indies, equal to those of the enemy. At particular times, indeed, this was not so; but speaking generally of the assignment of ships, the statement is correct. In Europe, on the contrary, and in necessary consequence of the policy mentioned, the British fleet was habitually much inferior to that in the French and Spanish ports. It therefore could be used offensively only by great care, and through good fortune in meeting the enemy in detail; and even so an expensive victory, unless very decisive, entailed considerable risk from the consequent temporary disability of the ships engaged. It followed that the English home (or Channel) fleet, upon which depended also the communications with Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, was used very economically both as to battle and weather, and was confined to the defence of the home coast, or to operations against the enemy's communications.

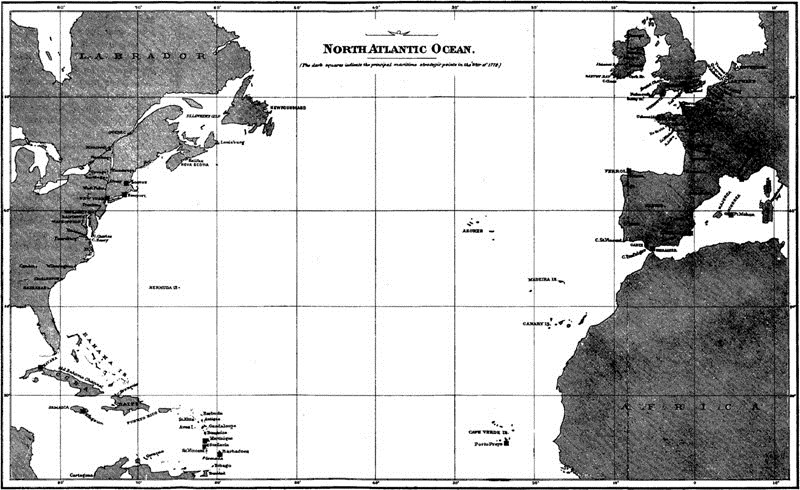

India was so far distant that no exception can be taken to the policy there. Ships sent there went to stay, and could be neither reinforced nor recalled with a view to sudden emergencies. The field stood by itself. But Europe, North America, and the West Indies should have been looked upon as one large theatre of war, throughout which events were mutually dependent, and whose different parts stood in close relations of greater or less importance, to which due attention should have been paid.

Assuming that the navies, as the guardians of the communications, were the controlling factors in the war, and that the source, both of the navies and of those streams of supplies which are called communications, was in the mother-countries, and there centralized in the chief arsenals, two things follow: First, the main effort of the Power standing on the defensive, of Great Britain, should have been concentrated before those arsenals; and secondly, in order to such concentration, the lines of communication abroad should not have been needlessly extended, so as to increase beyond the strictest necessity the detachments to guard them. Closely connected with the last consideration is the duty of strengthening, by fortification and otherwise, the vital points to which the communications led, so that these points should not depend in any way upon the fleet for protection, but only for supplies and reinforcements, and those at reasonable intervals. Gibraltar, for instance, quite fulfilled these conditions, being practically impregnable, and storing supplies that lasted very long.

If this reasoning be correct, the English dispositions on the American continent were very faulty. Holding Canada, with Halifax, New York, and Narragansett Bay, and with the line of the Hudson within their grip, it was in their power to isolate a large, perhaps decisive, part of the insurgent territory. New York and Narragansett Bay could have been made unassailable by a French fleet of that day, thus assuring the safety of the garrisons against attacks from the sea and minimizing the task of the navy; while the latter would find in them a secure refuge, in case an enemy's force eluded the watch of the English fleet before a European arsenal and appeared on the coast. Instead of this, these two ports were left weak, and would have fallen before a Nelson or a Farragut, while the army in New York was twice divided, first to the Chesapeake and afterward to Georgia, neither part of the separated forces being strong enough for the work before it. The control of the sea was thus used in both cases to put the enemy between the divided portions of the English army, when the latter, undivided, had not been able to force its way over the ground thus interposed. As the communication between the two parts of the army depended wholly upon the sea, the duty of the navy was increased with the increased length of the lines of communication. The necessity of protecting the seaports and the lengthened lines of communication thus combined to augment the naval detachments in America, and to weaken proportionately the naval force at the decisive points in Europe. Thus also a direct consequence of the southern expedition was the hasty abandonment of Narragansett Bay, when D'Estaing appeared on the coast in 1779, because Clinton had not force enough to defend both it and New York.240

In the West Indies the problem before the English government was not to subdue revolted territory, but to preserve the use of a number of small, fruitful islands; to keep possession of them itself, and to maintain their trade as free as possible from the depredations of the enemy. It need not be repeated that this demanded predominance at sea over both the enemy's fleets and single cruisers,—"commerce-destroyers," as the latter are now styled. As no vigilance can confine all these to their ports, the West Indian waters must be patrolled by British frigates and lighter vessels; but it would surely be better, if possible, to keep the French fleet away altogether than to hold it in check by a British fleet on the spot, of only equal force at any time, and liable to fall, as it often did, below equality. England, being confined to the defensive, was always liable to loss when thus inferior. She actually did lose one by one, by sudden attack, most of her islands, and at different times had her fleet shut up under the batteries of a port; whereas the enemy, when he found himself inferior, was able to wait for reinforcements, knowing that he had nothing to fear while so waiting.241

Nor was this embarrassment confined to the West Indies. The nearness of the islands to the American continent made it always possible for the offence to combine his fleets in the two quarters before the defence could be sure of his purpose; and although such combinations were controlled in some measure by well-understood conditions of weather and the seasons, the events of 1780 and 1781 show the perplexity felt from this cause by the ablest English admiral, whose dispositions, though faulty, but reflected the uncertainties of his mind. When to this embarrassment, which is common to the defensive in all cases, is added the care of the great British trade upon which the prosperity of the empire mainly depended, it must be conceded that the task of the British admiral in the West Indies was neither light nor simple.

In Europe, the safety of England herself and of Gibraltar was gravely imperilled by the absence of these large detachments in the Western Hemisphere, to which may also be attributed the loss of Minorca. When sixty-six allied ships-of-the-line confronted the thirty-five which alone England could collect, and drove them into their harbors, there was realized that mastery of the Channel which Napoleon claimed would make him beyond all doubt master of England. For thirty days, the thirty ships which formed the French contingent had cruised in the Bay of Biscay, awaiting the arrival of the tardy Spaniards; but they were not disturbed by the English fleet. Gibraltar was more than once brought within sight of starvation, through the failure of communications with England; and its deliverance was due, not to the power of the English navy suitably disposed by its government, but to the skill of British officers and the inefficiency of the Spaniards. In the great final relief, Lord Howe's fleet numbered only thirty-four to the allied forty-nine.

Which, then, in the difficulties under which England labored, was the better course,—to allow the enemy free exit from his ports and endeavor to meet him by maintaining a sufficient naval force on each of the exposed stations, or to attempt to watch his arsenals at home, under all the difficulties of the situation, not with the vain hope of preventing every raid, or intercepting every convoy, but with the expectation of frustrating the greater combinations, and of following close at the heels of any large fleet that escaped? Such a watch must not be confounded with a blockade, a term frequently, but not quite accurately, applied to it. "I beg to inform your Lordship," wrote Nelson, "that the port of Toulon has never been blockaded by me; quite the reverse. Every opportunity has been offered the enemy to put to sea, for it is there we hope to realize the hopes and expectations of our country." "Nothing," he says again, "ever kept the French fleet in Toulon or Brest when they had a mind to come out;" and although the statement is somewhat exaggerated, it is true that the attempt to shut them up in port would have been hopeless. What Nelson expected by keeping near their ports, with enough lookout ships properly distributed, was to know when they sailed and what direction they took, intending, to use his own expression, to "follow them to the antipodes." "I am led to believe," he writes at another time, "that the Ferrol squadron of French ships will push for the Mediterranean. If it join that in Toulon, it will much outnumber us; but I shall never lose sight of them, and Pellew (commanding the English squadron off Ferrol) will soon be after them." So it happened often enough during that prolonged war that divisions of French ships escaped, through stress of weather, temporary absence of a blockading fleet, or misjudgment on the part of its commander; but the alarm was quickly given, some of the many frigates caught sight of them, followed to detect their probable destination, passed the word from point to point and from fleet to fleet, and soon a division of equal force was after them, "to the antipodes" if need were. As, according to the traditional use of the French navy by French governments, their expeditions went not to fight the hostile fleet, but with "ulterior objects," the angry buzz and hot pursuit that immediately followed was far from conducive to an undisturbed and methodical execution of the programme laid down, even by a single division; while to great combinations, dependent upon uniting the divisions from different ports, they were absolutely fatal. The adventurous cruise of Bruix, leaving Brest with twenty-five ships-of-the-line in 1799, the rapidity with which the news spread, the stirring action and individual mistakes of the English, the frustration of the French projects242 and the closeness of the pursuit,243 the escape of Missiessy from Rochefort in 1805, of the divisions of Willaumez and Leissegues from Brest in 1806,—all these may be named, along with the great Trafalgar campaign, as affording interesting studies of a naval strategy following the lines here suggested; while the campaign of 1798, despite its brilliant ending at the Nile, may be cited as a case where failure nearly ensued, owing to the English having no force before Toulon when the expedition sailed, and to Nelson being insufficiently provided with frigates. The nine weeks' cruise of Ganteaume in the Mediterranean, in 1808, also illustrates the difficulty of controlling a fleet which has been permitted to get out, unwatched by a strong force, even in such narrow waters.

North Atlantic Ocean.

No parallel instances can be cited from the war of 1778, although the old monarchy did not cover the movements of its fleets with the secrecy enforced by the stern military despotism of the Empire. In both epochs England stood on the defensive; but in the earlier war she gave up the first line of the defence, off the hostile ports, and tried to protect all parts of her scattered empire by dividing the fleet among them. It has been attempted to show the weakness of the one policy, while admitting the difficulties and dangers of the other. The latter aims at shortening and deciding the war by either shutting up or forcing battle upon the hostile navy, recognizing that this is the key of the situation, when the sea at once unites and separates the different parts of the theatre of war. It requires a navy equal in number and superior in efficiency, to which it assigns a limited field of action, narrowed to the conditions which admit of mutual support among the squadrons occupying it. Thus distributed, it relies upon skill and watchfulness to intercept or overtake any division of the enemy which gets to sea. It defends remote possessions and trade by offensive action against the fleet, in which it sees their real enemy and its own principal objective. Being near the home ports, the relief and renewal of ships needing repairs are accomplished with the least loss of time, while the demands upon the scantier resources of the bases abroad are lessened. The other policy, to be effective, calls for superior numbers, because the different divisions are too far apart for mutual support. Each must therefore be equal to any probable combination against it, which implies superiority everywhere to the force of the enemy actually opposed, as the latter may be unexpectedly reinforced. How impossible and dangerous such a defensive strategy is, when not superior in force, is shown by the frequent inferiority of the English abroad, as well as in Europe, despite the effort to be everywhere equal. Howe at New York in 1778, Byron at Grenada in 1779, Graves off the Chesapeake in 1781, Hood at Martinique in 1781 and at St. Kitt's in 1782, all were inferior, at the same time that the allied fleet in Europe overwhelmingly outnumbered the English. In consequence, unseaworthy ships were retained, to the danger of their crews and their own increasing injury, rather than diminish the force by sending them home; for the deficiencies of the colonial dock-yards did not allow extensive repairs without crossing the Atlantic. As regards the comparative expense of the two strategies, the question is not only which would cost the more in the same time, but which would most tend to shorten the war by the effectiveness of its action.

The military policy of the allies is open to severer condemnation than that of England, by so much as the party assuming the offensive has by that very fact an advantage over the defensive. When the initial difficulty of combining their forces was overcome,—and it has been seen that at no time did Great Britain seriously embarrass their junction,—the allies had the choice open to them where, when, and how to strike with their superior numbers. How did they avail themselves of this recognized enormous advantage? By nibbling at the outskirts of the British Empire, and knocking their heads against the Rock of Gibraltar. The most serious military effort made by France, in sending to the United States a squadron and division of troops intended to be double the number of those which actually reached their destination, resulted, in little over a year, in opening the eyes of England to the hopelessness of the contest with the colonies and thus put an end to a diversion of her strength which had been most beneficial to her opponents. In the West Indies one petty island after another was reduced, generally in the absence of the English fleet, with an ease which showed how completely the whole question would have been solved by a decisive victory over that fleet; but the French, though favored with many opportunities, never sought to slip the knot by the simple method of attacking the force upon which all depended. Spain went her own way in the Floridas, and with an overwhelming force obtained successes of no military value. In Europe the plan adopted by the English government left its naval force hopelessly inferior in numbers year after year; yet the operations planned by the allies seem in no case seriously to have contemplated the destruction of that force. In the crucial instance, when Derby's squadron of thirty sail-of-the-line was hemmed in the open roadstead of Torbay by the allied forty-nine, the conclusion of the council of war not to fight only epitomized the character of the action of the combined navies. To further embarrass their exertions in Europe, Spain, during long periods, obstinately persisted in tying down her fleet to the neighborhood of Gibraltar; but there was at no time practical recognition of the fact that a severe blow to the English navy in the Straits, or in the English Channel, or on the open sea, was the surest road to reduce the fortress, brought more than once within measurable distance of starvation.

In the conduct of their offensive war the allied courts suffered from the divergent counsels and jealousies which have hampered the movements of most naval coalitions. The conduct of Spain appears to have been selfish almost to disloyalty, that of France more faithful, and therefore also militarily sounder; for hearty co-operation and concerted action against a common objective, wisely chosen, would have better forwarded the objects of both. It must be admitted, too, that the indications point to inefficient administration and preparation on the part of the allies, of Spain especially; and that the quality of the personnel244 was inferior to that of England. Questions of preparation and administration, however, though of deep military interest and importance, are very different from the strategic plan or method adopted by the allied courts in selecting and attacking their objectives, and so compassing the objects of the war; and their examination would not only extend this discussion unreasonably, but would also obscure the strategic question by heaping up unnecessary details foreign to its subject.

As regards the strategic question, it may be said pithily that the phrase "ulterior objects" embodies the cardinal fault of the naval policy. Ulterior objects brought to nought the hopes of the allies, because, by fastening their eyes upon them, they thoughtlessly passed the road which led to them. Desire eagerly directed upon the ends in view—or rather upon the partial, though great, advantages which they constituted their ends—blinded them to the means by which alone they could be surely attained; hence, as the result of the war, everywhere failure to attain them. To quote again the summary before given, their object was "to avenge their respective injuries, and to put an end to that tyrannical empire which England claims to maintain upon the ocean." The revenge they had obtained was barren of benefit to themselves. They had, so that generation thought, injured England by liberating America; but they had not righted their wrongs in Gibraltar and Jamaica, the English fleet had not received any such treatment as would lessen its haughty self-reliance, the armed neutrality of the northern powers had been allowed to pass fruitlessly away, and the English empire over the seas soon became as tyrannical and more absolute than before.

Barring questions of preparation and administration, of the fighting quality of the allied fleets as compared with the English, and looking only to the indisputable fact of largely superior numbers, it must be noted as the supreme factor in the military conduct of the war, that, while the allied powers were on the offensive and England on the defensive, the attitude of the allied fleets in presence of the English navy was habitually defensive. Neither in the greater strategic combinations, nor upon the battlefield, does there appear any serious purpose of using superior numbers to crush fractions of the enemy's fleet, to make the disparity of numbers yet greater, to put an end to the empire of the seas by the destruction of the organized force which sustained it. With the single brilliant exception of Suffren, the allied navies avoided or accepted action; they never imposed it. Yet so long as the English navy was permitted thus with impunity to range the seas, not only was there no security that it would not frustrate the ulterior objects of the campaign, as it did again and again, but there was always the possibility that by some happy chance it would, by winning an important victory, restore the balance of strength. That it did not do so is to be imputed as a fault to the English ministry; but if England was wrong in permitting her European fleet to fall so far below that of the allies, the latter were yet more to blame for their failure to profit by the mistake. The stronger party, assuming the offensive, cannot plead the perplexities which account for, though they do not justify, the undue dispersal of forces by the defence anxious about many points.