полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Having carried out their orders for the summer cruise, the combined fleets returned to Cadiz. On the 10th of September they sailed thence for Algesiras, on the opposite side of the bay from Gibraltar, to support a grand combined attack by land and sea, which, it was hoped, would reduce to submission the key to the Mediterranean. With the ships already there, the total rose to nearly fifty ships-of-the-line. The details of the mighty onslaught scarcely belong to our subject, yet cannot be wholly passed by, without at least such mention as may recognize and draw attention to their interest.

The three years' siege which was now drawing to its end had been productive of many brilliant feats of arms, as well as of less striking but more trying proofs of steadfast endurance, on the part of the garrison. How long the latter might have held out cannot be said, seeing the success with which the English sea power defied the efforts of the allies to cut off the communications of the fortress; but it was seemingly certain that the place must be subdued by main force or not at all, while the growing exhaustion of the belligerents foretold the near end of the war. Accordingly Spain multiplied her efforts of preparation and military ingenuity; while the report of them and of the approaching decisive contest drew to the scene volunteers and men of eminence from other countries of Europe. Two French Bourbon princes added, by their coming, to the theatrical interest with which the approaching drama was invested. The presence of royalty was needed adequately to grace the sublime catastrophe; for the sanguine confidence of the besiegers had determined a satisfactory dénouement with all the security of a playwright.

Besides the works on the isthmus which joins the Rock to the mainland, where three hundred pieces of artillery were now mounted, the chief reliance of the assailants was upon ten floating batteries elaborately contrived to be shot and fire proof, and carrying one hundred and fifty-four heavy guns. These were to anchor in a close north-and-south line along the west face of the works, at about nine hundred yards distance. They were to be supported by forty gunboats and as many bomb vessels, besides the efforts of the ships-of-the-line to cover the attack and distract the garrison. Twelve thousand French troops were brought to reinforce the Spaniards in the grand assault, which was to be made when the bombardment had sufficiently injured and demoralized the defenders. At this time the latter numbered seven thousand, their land opponents thirty-three thousand men.

The final act was opened by the English. At seven o'clock on the morning of September 8, 1782, the commanding general, Elliott, began a severe and most injurious fire upon the works on the isthmus. Having effected his purpose, he stopped; but the enemy took up the glove the next morning, and for four days successively poured in a fire from the isthmus alone of six thousand five hundred cannon-balls and one thousand one hundred bombs every twenty-four hours. So approached the great closing scene of September 13. At seven A.M. of that day the ten battering-ships unmoored from the head of the bay and stood down to their station. Between nine and ten they anchored, and the general fire at once began. The besieged replied with equal fury. The battering-ships seem in the main, and for some hours, to have justified the hopes formed of them; cold shot glanced or failed to get through their sides, while the self-acting apparatus for extinguishing fires balked the hot shot.

About two o'clock, however, smoke was seen to issue from the ship of the commander-in-chief, and though controlled for some time, the fire continued to gain. The same misfortune befell others; by evening, the fire of the besieged gained a marked superiority, and by one o'clock in the morning the greater part of the battering-ships were in flames. Their distress was increased by the action of the naval officer commanding the English gunboats, who now took post upon the flank of the line and raked it effectually,—a service which the Spanish gunboats should have prevented. In the end, nine of the ten blew up at their anchors, with a loss estimated at fifteen hundred men, four hundred being saved from the midst of the fire by the English seamen. The tenth ship was boarded and burned by the English boats. The hopes of the assailants perished with the failure of the battering-ships.

There remained only the hope of starving out the garrison. To this end the allied fleets now gave themselves. It was known that Lord Howe was on his way out with a great fleet, numbering thirty-four ships-of-the-line, besides supply vessels. On the 10th of October a violent westerly gale injured the combined ships, driving one ashore under the batteries of Gibraltar, where she was surrendered. The next day Howe's force came in sight, and the transports had a fine chance to make the anchorage, which, through carelessness, was missed by all but four. The rest, with the men-of-war, drove eastward into the Mediterranean. The allies followed on the 13th; but though thus placed between the port and the relieving force, and not encumbered, like the latter, with supply-ships, they yet contrived to let the transports, with scarcely an exception, slip in and anchor safely. Not only provisions and ammunition, but also bodies of troops carried by the ships-of-war, were landed without molestation. On the 19th the English fleet repassed the straits with an easterly wind, having within a week's time fulfilled its mission, and made Gibraltar safe for another year. The allied fleet followed, and on the 20th an action took place at long range, the allies to windward, but not pressing their attack close. The number of ships engaged in this magnificent spectacle, the closing scene of the great drama in Europe, the after-piece to the successful defence of Gibraltar, was eighty-three of the line,—forty-nine allies and thirty-four English. Of the former, thirty-three only got into action; but as the duller sailers would have come up to a general engagement, Lord Howe was probably right in declining, so far as in him lay, a trial which the allies did not too eagerly court.

Such were the results of this great contest in the European seas, marked on the part of the allies by efforts gigantic in size, but loose-jointed and flabby in execution. By England, so heavily overmatched in mere numbers, were shown firmness of purpose, high courage, and seamanship; but it can scarcely be said that the military conceptions of her councils, or the cabinet management of her sea forces, were worthy of the skill and devotion of her seamen. The odds against her were not so great—not nearly so great—as the formidable lists of guns and ships seemed to show; and while allowance must justly be made for early hesitations, the passing years of indecision and inefficiency on the part of the allies should have betrayed to her their weakness. The reluctance of the French to risk their ships, so plainly shown by D'Estaing, De Grasse, and De Guichen, the sluggishness and inefficiency of the Spaniards, should have encouraged England to pursue her old policy, to strike at the organized forces of the enemy afloat. As a matter of fact, and probably from the necessities of the case, the opening of every campaign found the enemies separated,—the Spaniards in Cadiz, the French in Brest.164 To blockade the latter in full force before they could get out, England should have strained every effort; thus she would have stopped at its head the main stream of the allied strength, and, by knowing exactly where this great body was, would have removed that uncertainty as to its action which fettered her own movements as soon as it had gained the freedom of the open sea. Before Brest she was interposed between the allies; by her lookouts she would have known the approach of the Spaniards long before the French could know it; she would have kept in her hands the power of bringing against each, singly, ships more numerous and individually more effective. A wind that was fair to bring on the Spaniards would have locked their allies in the port. The most glaring instances of failure on the part of England to do this were when De Grasse was permitted to get out unopposed in March, 1781; for an English fleet of superior force had sailed from Portsmouth nine days before him, but was delayed by the admiralty on the Irish coast;165 and again at the end of that year, when Kempenfeldt was sent to intercept De Guichen with an inferior force, while ships enough to change the odds were kept at home. Several of the ships which were to accompany Rodney to the West Indies were ready when Kempenfeldt sailed, yet they were not associated with an enterprise so nearly affecting the objects of Rodney's campaign. The two forces united would have made an end of De Guichen's seventeen ships and his invaluable convoy.

Gibraltar was indeed a heavy weight upon the English operations, but the national instinct which clung to it was correct. The fault of the English policy was in attempting to hold so many other points of land, while neglecting, by rapidity of concentration, to fall upon any of the detachments of the allied fleets. The key of the situation was upon the ocean; a great victory there would have solved all the other points in dispute. But it was not possible to win a great victory while trying to maintain a show of force everywhere.166

North America was a yet heavier clog, and there undoubtedly the feeling of the nation was mistaken; pride, not wisdom, maintained that struggle. Whatever the sympathies of individuals and classes in the allied nations, by their governments American rebellion was valued only as a weakening of England's arm. The operations there depended, as has been shown, upon the control of the sea; and to maintain that, large detachments of English ships were absorbed from the contest with France and Spain. Could a successful war have made America again what it once was, a warmly attached dependency of Great Britain, a firm base for her sea power, it would have been worth much greater sacrifices; but that had become impossible. But although she had lost, by her own mistakes, the affection of the colonists, which would have supported and secured her hold upon their ports and sea-coast, there nevertheless remained to the mother-country, in Halifax, Bermuda, and the West Indies, enough strong military stations, inferior, as naval bases, only to those strong ports which are surrounded by a friendly country, great in its resources and population. The abandonment of the contest in North America would have strengthened England very much more than the allies. As it was, her large naval detachments there were always liable to be overpowered by a sudden move of the enemy from the sea, as happened in 1778 and 1781.

To the abandonment of America as hopelessly lost, because no military subjection could have brought back the old loyalty, should have been added the giving up, for the time, all military occupancy which fettered concentration, while not adding to military strength. Most of the Antilles fell under this head, and the ultimate possession of them would depend upon the naval campaign. Garrisons could have been spared for Barbadoes and Sta. Lucia, for Gibraltar and perhaps for Mahon, that could have effectually maintained them until the empire of the seas was decided; and to them could have been added one or two vital positions in America, like New York and Charleston, to be held only till guarantees were given for such treatment of the loyalists among the inhabitants as good faith required England to exact.

Having thus stripped herself of every weight, rapid concentration with offensive purpose should have followed. Sixty ships-of-the-line on the coast of Europe, half before Cadiz and half before Brest, with a reserve at home to replace injured ships, would not have exhausted by a great deal the roll of the English navy; and that such fleets would not have had to fight, may not only be said by us, who have the whole history before us, but might have been inferred by those who had watched the tactics of D'Estaing and De Guichen, and later on of De Grasse. Or, had even so much dispersal been thought unadvisable, forty ships before Brest would have left the sea open to the Spanish fleet to try conclusions with the rest of the English navy when the question of controlling Gibraltar and Mahon came up for decision. Knowing what we do of the efficiency of the two services, there can be little question of the result; and Gibraltar, instead of a weight, would, as often before and since those days, have been an element of strength to Great Britain.

The conclusion continually recurs. Whatever may be the determining factors in strifes between neighboring continental States, when a question arises of control over distant regions, politically weak,—whether they be crumbling empires, anarchical republics, colonies, isolated military posts, or islands below a certain size,—it must ultimately be decided by naval power, by the organized military force afloat, which represents the communications that form so prominent a feature in all strategy. The magnificent defence of Gibraltar hinged upon this; upon this depended the military results of the war in America; upon this the final fate of the West India Islands; upon this certainly the possession of India. Upon this will depend the control of the Central American Isthmus, if that question take a military coloring; and though modified by the continental position and surroundings of Turkey, the same sea power must be a weighty factor in shaping the outcome of the Eastern Question in Europe.

If this be true, military wisdom and economy, both of time and money, dictate bringing matters to an issue as soon as possible upon the broad sea, with the certainty that the power which achieves military preponderance there will win in the end. In the war of the American Revolution the numerical preponderance was very great against England; the actual odds were less, though still against her. Military considerations would have ordered the abandonment of the colonies; but if the national pride could not stoop to this, the right course was to blockade the hostile arsenals. If not strong enough to be in superior force before both, that of the more powerful nation should have been closed. Here was the first fault of the English admiralty; the statement of the First Lord as to the available force at the outbreak of the war was not borne out by facts. The first fleet, under Keppel, barely equalled the French; and at the same time Howe's force in America was inferior to the fleet under D'Estaing. In 1779 and 1781, on the contrary, the English fleet was superior to that of the French alone; yet the allies joined unopposed, while in the latter year De Grasse got away to the West Indies, and Suffren to the East. In Kempenfeldt's affair with De Guichen, the admiralty knew that the French convoy was of the utmost importance to the campaign in the West Indies, yet they sent out their admiral with only twelve ships; while at that time, besides the reinforcement destined for the West Indies, a number of others were stationed in the Downs, for what Fox justly called "the paltry purpose" of distressing the Dutch trade. The various charges made by Fox in the speech quoted from, and which, as regarded the Franco-Spanish War, were founded mainly on the expediency of attacking the allies before they got away into the ocean wilderness, were supported by the high professional opinion of Lord Howe, who of the Kempenfeldt affair said: "Not only the fate of the West India Islands, but perhaps the whole future fortune of the war, might have been decided, almost without a risk, in the Bay of Biscay."167 Not without a risk, but with strong probabilities of success, the whole fortune of the war should at the first have been staked on a concentration of the English fleet between Brest and Cadiz. No relief for Gibraltar would have been more efficacious; no diversion surer for the West India Islands; and the Americans would have appealed in vain for the help, scantily given as it was, of the French fleet. For the great results that flowed from the coming of De Grasse must not obscure the fact that he came on the 31st of August, and announced from the beginning that he must be in the West Indies again by the middle of October. Only a providential combination of circumstances prevented a repetition to Washington, in 1781, of the painful disappointments by D'Estaing and De Guichen in 1778 and 1780.

CHAPTER XII

Events in the East Indies, 1778-1781.—Suffren sails from Brest, 1781.—His Brilliant Naval Campaign in the Indian Seas, 1782, 1783.

The very interesting and instructive campaign of Suffren in the East Indies, although in itself by far the most noteworthy and meritorious naval performance of the war of 1778, failed, through no fault of his, to affect the general issue. It was not till 1781 that the French Court felt able to direct upon the East naval forces adequate to the importance of the issue. Yet the conditions of the peninsula at that time were such as to give an unusual opportunity for shaking the English power. Hyder Ali, the most skilful and daring of all the enemies against whom the English had yet fought in India, was then ruling over the kingdom of Mysore, which, from its position in the southern part of the peninsula, threatened both the Carnatic and the Malabar coast. Hyder, ten years before, had maintained alone a most successful war against the intruding foreigners, concluding with a peace upon the terms of a mutual restoration of conquests; and he was now angered by the capture of Mahé. On the other hand, a number of warlike tribes, known by the name of the Mahrattas, of the same race and loosely knit together in a kind of feudal system, had become involved in war with the English. The territory occupied by these tribes, whose chief capital was at Poonah, near Bombay, extended northward from Mysore to the Ganges. With boundaries thus conterminous, and placed centrally with reference to the three English presidencies of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, Hyder and the Mahrattas were in a position of advantage for mutual support and for offensive operations against the common enemy. At the beginning of the war between England and France, a French agent appeared at Poonah. It was reported to Warren Hastings, the Governor-General, that the tribes had agreed to terms and ceded to the French a seaport on the Malabar coast. With his usual promptness, Hastings at once determined on war, and sent a division of the Bengal army across the Jumna and into Berar. Another body of four thousand English troops also marched from Bombay; but being badly led, was surrounded and forced to surrender in January, 1779. This unusual reverse quickened the hopes and increased the strength of the enemies of the English; and although the material injury was soon remedied by substantial successes under able leaders, the loss of prestige remained. The anger of Hyder Ali, roused by the capture of Mahé, was increased by imprudent thwarting on the part of the governor of Madras. Seeing the English entangled with the Mahrattas, and hearing that a French armament was expected on the Coromandel coast, he quietly prepared for war. In the summer of 1780 swarms of his horsemen descended without warning from the hills, and appeared near the gates of Madras. In September one body of English troops, three thousand strong, was cut to pieces, and another of five thousand was only saved by a rapid retreat upon Madras, losing its artillery and trains. Unable to attack Madras, Hyder turned upon the scattered posts separated from each other and the capital by the open country, which was now wholly in his control.

Such was the state of affairs when, in January, 1781, a French squadron of six ships-of-the-line and three frigates appeared on the coast. The English fleet under Sir Edward Hughes had gone to Bombay. To the French commodore, Count d'Orves, Hyder appealed for aid in an attack upon Cuddalore. Deprived of support by sea, and surrounded by the myriads of natives, the place must have fallen. D'Orves, however, refused, and returned to the Isle of France. At the same time one of the most skilful of the English Indian soldiers, Sir Eyre Coote, took the field against Hyder. The latter at once raised the siege of the beleaguered posts, and after a series of operations extending through the spring months, was brought to battle on the 1st of July, 1781. His total defeat restored to the English the open country, saved the Carnatic, and put an end to the hopes of the partisans of the French in their late possession of Pondicherry. A great opportunity had been lost.

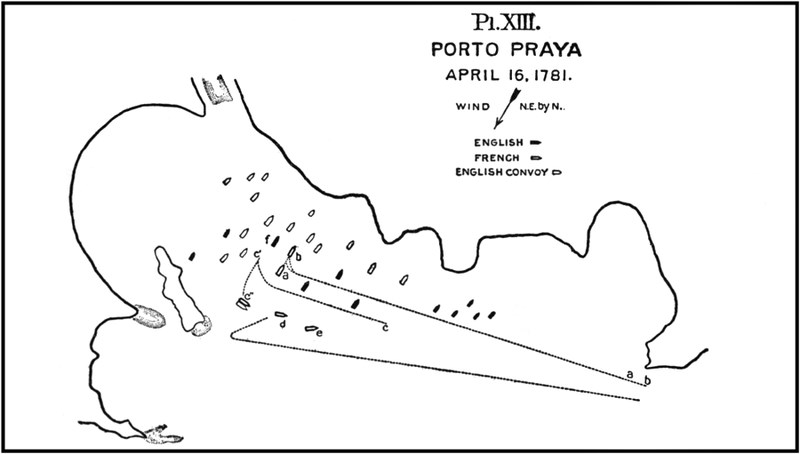

Meanwhile a French officer of very different temper from his predecessors was on his way to the East Indies. It will be remembered that when De Grasse sailed from Brest, March 22, 1781, for the West Indies, there went with his fleet a division of five ships-of-the-line under Suffren. The latter separated from the main body on the 29th of the month, taking with him a few transports destined for the Cape of Good Hope, then a Dutch colony. The French government had learned that an expedition from England was destined to seize this important halting-place on the road to India, and Suffren's first mission was to secure it. In fact, the squadron under Commodore Johnstone168 had got away first, and had anchored at Porto Praya, in the Cape Verde Islands, a Portuguese colony, on the 11th of April. It numbered two ships-of-the-line, and three of fifty guns, with frigates and smaller vessels, besides thirty-five transports, mostly armed. Without apprehension of attack, not because he trusted to the neutrality of the port but because he thought his destination secret, the English commodore had not anchored with a view to battle.

It so happened that at the moment of sailing from Brest one of the ships intended for the West Indies was transferred to Suffren's squadron. She consequently had not water enough for the longer voyage, and this with other reasons determined Suffren also to anchor at Porto Praya. On the 16th of April, five days after Johnstone, he made the island early in the morning and stood for the anchorage, sending a coppered ship ahead to reconnoitre. Approaching from the eastward, the land for some time hid the English squadron; but at quarter before nine the advance ship, the "Artésien," signalled that enemy's ships were anchored in the bay. The latter is open to the southward, and extends from east to west about a mile and a half; the conditions are such that ships usually lie in the northeast part, near the shore (Plate XIII).169 The English were there, stretching irregularly in a west-northwest line. Both Suffren and Johnstone were surprised, but the latter more so; and the initiative remained with the French officer. Few men were fitter, by natural temper and the teaching of experience, for the prompt decision required. Of ardent disposition and inborn military genius, Suffren had learned, in the conduct of Boscawen toward the squadron of De la Clue,170 in which he had served, not to lay weight upon the power of Portugal to enforce respect for her neutrality. He knew that this must be the squadron meant for the Cape of Good Hope. The only question for him was whether to press on to the Cape with the chance of getting there first, or to attack the English at their anchors, in the hope of so crippling them as to prevent their further progress. He decided for the latter; and although the ships of his squadron, not sailing equally well, were scattered, he also determined to stand in at once, rather than lose the advantage of a surprise. Making signal to prepare for action at anchor, he took the lead in his flag-ship, the "Héros," of seventy-four guns, hauled close round the southeast point of the bay, and stood for the English flag-ship (f). He was closely followed by the "Hannibal," seventy-four (line a b); the advance ship "Artésien" (c), a sixty-four, also stood on with him; but the two rear ships were still far astern.

Pl. XIII.

The English commodore got ready for battle as soon as he made out the enemy, but had no time to rectify his order. Suffren anchored five hundred feet from the flag-ship's starboard beam (by a singular coincidence the English flag-ship was also called "Hero"), thus having enemy's ships on both sides, and opened fire. The "Hannibal" anchored ahead of her commodore (b), and so close that the latter had to veer cable and drop astern (a); but her captain, ignorant of Suffren's intention to disregard the neutrality of the port, had not obeyed the order to clear for action, and was wholly unprepared,—his decks lumbered with water-casks which had been got up to expedite watering, and the guns not cast loose. He did not add to this fault by any hesitation, but followed the flag-ship boldly, receiving passively the fire, to which for a time he was unable to reply. Luffing to the wind, he passed to windward of his chief, chose his position with skill, and atoned by his death for his first fault. These two ships were so placed as to use both broadsides. The "Artésien," in the smoke, mistook an East India ship for a man-of-war. Running alongside (c’), her captain was struck dead at the moment he was about to anchor, and the critical moment being lost by the absence of a head, the ship drifted out of close action, carrying the East-Indiaman along with her (c’’). The remaining two vessels, coming up late, failed to keep close enough to the wind, and they too were thrown out of action (d, e). Then Suffren, finding himself with only two ships to bear the brunt of the fight, cut his cable and made sail. The "Hannibal" followed his movement; but so much injured was she that her fore and main masts went over the side,—fortunately not till she was pointed out from the bay, which she left shorn to a hulk.