полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

The following day, April 30, De Grasse, having thrown away his chance, attempted to follow Hood; but the latter had no longer any reason for fighting, and his original inferiority was increased by the severe injuries of some ships on the 29th. De Grasse could not overtake him, owing to the inferior speed of his fleet, many of the ships not being coppered,—a fact worthy of note, as French vessels by model and size were generally faster than English; but this superiority was sacrificed through the delay of the government in adopting the new improvement.

Hood rejoined Rodney at Antigua; and De Grasse, after remaining a short time at Fort Royal, made an attempt upon Gros Ilot Bay, the possession of which by the English kept all the movements of his fleet under surveillance. Foiled here, he moved against Tobago, which surrendered June 2, 1781. Sailing thence, after some minor operations, he anchored on the 26th of July at Cap Français (now Cape Haytien), in the island of Hayti. Here he found awaiting him a French frigate from the United States, bearing despatches from Washington and Rochambeau, upon which he was to take the most momentous action that fell to any French admiral during the war.

The invasion of the Southern States by the English, beginning in Georgia and followed by the taking of Charleston and the military control of the two extreme States, had been pressed on to the northward by way of Camden into North Carolina. On the 16th of August, 1780, General Gates was totally defeated at Camden; and during the following nine months the English under Cornwallis persisted in their attempts to overrun North Carolina. These operations, the narration of which is foreign to our immediate subject, had ended by forcing Cornwallis, despite many successes in actual encounter, to fall back exhausted toward the seaboard, and finally upon Wilmington, in which place depots for such a contingency had been established. His opponent, General Greene, then turned the American troops toward South Carolina. Cornwallis, too weak to dream of controlling, or even penetrating, into the interior of an unfriendly country, had now to choose between returning to Charleston, to assure there and in South Carolina the shaken British power, and moving northward again into Virginia, there to join hands with a small expeditionary force operating on the James River under Generals Phillips and Arnold. To fall back would be a confession that the weary marching and fighting of months past had been without results, and the general readily convinced himself that the Chesapeake was the proper seat of war, even if New York itself had to be abandoned. The commander-in-chief, Sir Henry Clinton, by no means shared this opinion, upon which was justified a step taken without asking him. "Operations in the Chesapeake," he wrote, "are attended with great risk unless we are sure of a permanent superiority at sea. I tremble for the fatal consequences that may ensue." For Cornwallis, taking the matter into his own hands, had marched from Wilmington on the 25th of April, 1781, joining the British already at Petersburg on the 20th of May. The forces thus united numbered seven thousand men. Driven back from the open country of South Carolina into Charleston, there now remained two centres of British power,—at New York and in the Chesapeake. With New Jersey and Pennsylvania in the hands of the Americans, communication between the two depended wholly upon the sea.

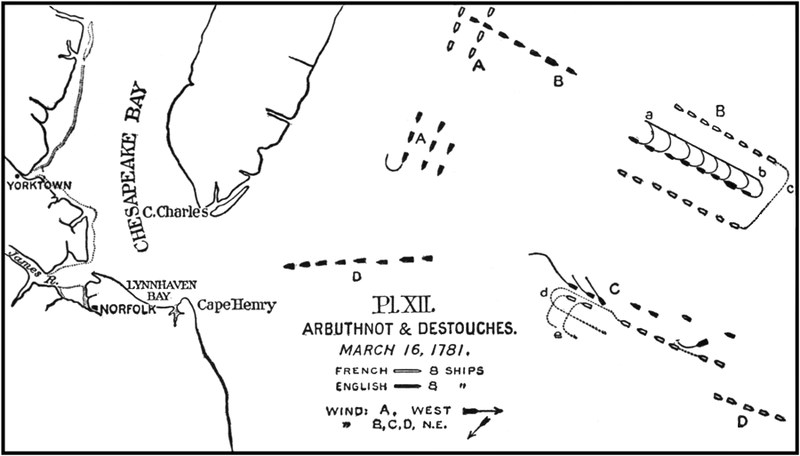

Despite his unfavorable criticism of Cornwallis's action, Clinton had himself already risked a large detachment in the Chesapeake. A body of sixteen hundred men under Benedict Arnold had ravaged the country of the James and burned Richmond in January of this same year. In the hopes of capturing Arnold, Lafayette had been sent to Virginia with a nucleus of twelve hundred troops, and on the evening of the 8th of March the French squadron at Newport sailed, in concerted movement, to control the waters of the bay. Admiral Arbuthnot, commanding the English fleet lying in Gardiner's Bay,145 learned the departure by his lookouts, and started in pursuit on the morning of the 10th, thirty-six hours later. Favored either by diligence or luck, he made such good time that when the two fleets came in sight of each other, a little outside of the capes of the Chesapeake, the English were leading146 (Plate XII., A, A). They at once went about to meet their enemy, who, on his part, formed a line-of-battle. The wind at this time was west, so that neither could head directly into the bay.

The two fleets were nearly equal in strength, there being eight ships on each side; but the English had one ninety-gun ship, while of the French one was only a heavy frigate, which was put into the line. Nevertheless, the case was eminently one for the general French policy to have determined the action of a vigorous chief, and the failure to see the matter through must fall upon the good-will of Commodore Destouches, or upon some other cause than that preference for the ulterior objects of the operations, of which the reader of French naval history hears so much. The weather was boisterous and threatening, and the wind, after hauling once or twice, settled down to northeast, with a big sea, but was then fair for entering the bay. The two fleets were by this time both on the port tack standing out to sea, the French leading, and about a point on the weather bow of the English (B, B). From this position they wore in succession (c) ahead of the latter, taking the lee-gage, and thus gaining the use of their lower batteries, which the heavy sea forbade to the weather-gage. The English stood on till abreast the enemy's line (a, b), when they wore together, and soon after attacked in the usual manner, and with the usual results (C). The three van ships were very badly injured aloft, but in their turn, throwing their force mainly on the two leaders of the enemy, crippled them seriously in hulls and rigging. The French van then kept away, and Arbuthnot, in perplexity, ordered his van to haul the wind again. M. Destouches now executed a very neat movement by defiling. Signalling his van to haul up on the other tack (e), he led the rest of his squadron by the disabled English ships, and after giving them the successive broadsides of his comparatively fresh ships, wore (d), and out to sea (D). This was the end of the battle, in which the English certainly got the worst; but with their usual tenacity of purpose, being unable to pursue their enemy afloat, they steered for the bay (D), made the junction with Arnold, and thus broke up the plans of the French and Americans, from which so much had been hoped by Washington. There can be no doubt, after careful reading of the accounts, that after the fighting the French were in better force than the English, and they in fact claimed the victory; yet the ulterior objects of the expedition did not tempt them again to try the issue with a fleet of about their own size.147

Pl. XII.

The way of the sea being thus open and held in force, two thousand more English troops sailing from New York reached Virginia on the 26th of March, and the subsequent arrival of Cornwallis in May raised the number to seven thousand. The operations of the contending forces during the spring and summer months, in which Lafayette commanded the Americans, do not concern our subject. Early in August, Cornwallis, acting under orders from Clinton, withdrew his troops into the peninsula between the York and James rivers, and occupied Yorktown.

Washington and Rochambeau had met on the 21st of May, and decided that the situation demanded that the effort of the French West Indian fleet, when it came, should be directed against either New York or the Chesapeake. This was the tenor of the despatch found by De Grasse at Cap Français, and meantime the allied generals drew their troops toward New York, where they would be on hand for the furtherance of one object, and nearer the second if they had to make for it.

In either case the result, in the opinion both of Washington and of the French government, depended upon superior sea power; but Rochambeau had privately notified the admiral that his own preference was for the Chesapeake as the scene of the intended operations, and moreover the French government had declined to furnish the means for a formal siege of New York.148 The enterprise therefore assumed the form of an extensive military combination, dependent upon ease and rapidity of movement, and upon blinding the eyes of the enemy to the real objective,—purposes to which the peculiar qualities of a navy admirably lent themselves. The shorter distance to be traversed, the greater depth of water and easier pilotage of the Chesapeake, were further reasons which would commend the scheme to the judgment of a seaman; and De Grasse readily accepted it, without making difficulties or demanding modifications which would have involved discussion and delay.

Having made his decision, the French admiral acted with great good judgment, promptitude, and vigor. The same frigate that brought despatches from Washington was sent back, so that by August 15th the allied generals knew of the intended coming of the fleet. Thirty-five hundred soldiers were spared by the governor of Cap Français, upon the condition of a Spanish squadron anchoring at the place, which De Grasse procured. He also raised from the governor of Havana the money urgently needed by the Americans; and finally, instead of weakening his force by sending convoys to France, as the court had wished, he took every available ship to the Chesapeake. To conceal his coming as long as possible, he passed through the Bahama Channel, as a less frequented route, and on the 30th of August anchored in Lynnhaven Bay, just within the capes of the Chesapeake, with twenty-eight ships-of-the-line. Three days before, August 27, the French squadron at Newport, eight ships-of-the-line with four frigates and eighteen transports under M. de Barras, sailed for the rendezvous; making, however, a wide circuit out to sea to avoid the English. This course was the more necessary as the French siege-artillery was with it. The troops under Washington and Rochambeau had crossed the Hudson on the 24th of August, moving toward the head of Chesapeake Bay. Thus the different armed forces, both land and sea, were converging toward their objective, Cornwallis.

The English were unfortunate in all directions. Rodney, learning of De Grasse's departure, sent fourteen ships-of-the-line under Admiral Hood to North America, and himself sailed for England in August, on account of ill health. Hood, going by the direct route, reached the Chesapeake three days before De Grasse, looked into the bay, and finding it empty went on to New York. There he met five ships-of-the-line under Admiral Graves, who, being senior officer, took command of the whole force and sailed on the 31st of August for the Chesapeake, hoping to intercept De Barras before he could join De Grasse. It was not till two days later that Sir Henry Clinton was persuaded that the allied armies had gone against Cornwallis, and had too far the start to be overtaken.

Admiral Graves was painfully surprised, on making the Chesapeake, to find anchored there a fleet which from its numbers could only be an enemy's. Nevertheless, he stood in to meet it, and as De Grasse got under way, allowing his ships to be counted, the sense of numerical inferiority—nineteen to twenty-four—did not deter the English admiral from attacking. The clumsiness of his method, however, betrayed his gallantry; many of his ships were roughly handled, without any advantage being gained. De Grasse, expecting De Barras, remained outside five days, keeping the English fleet in play without coming to action; then returning to port he found De Barras safely at anchor. Graves went back to New York, and with him disappeared the last hope of succor that was to gladden Cornwallis's eyes. The siege was steadily endured, but the control of the sea made only one issue possible, and the English forces were surrendered October 19, 1781. With this disaster the hope of subduing the colonies died in England. The conflict flickered through a year longer, but no serious operations were undertaken.

In the conduct of the English operations, which ended thus unfortunately, there was both bad management and ill fortune. Hood's detachment might have been strengthened by several ships from Jamaica, had Rodney's orders been carried out.149 The despatch-ship, also, sent by him to Admiral Graves commanding in New York, found that officer absent on a cruise to the eastward, with a view to intercept certain very important supplies which had been forwarded by the American agent in France. The English Court had laid great stress upon cutting off this convoy; but, with the knowledge that he had of the force accompanying it, the admiral was probably ill-advised in leaving his headquarters himself, with all his fleet, at the time when the approach of the hurricane season in the West Indies directed the active operations of the navies toward the continent. In consequence of his absence, although Rodney's despatches were at once sent on by the senior officer in New York, the vessel carrying them being driven ashore by enemy's cruisers, Graves did not learn their contents until his return to port, August 16. The information sent by Hood of his coming was also intercepted. After Hood's arrival, it does not appear that there was avoidable delay in going to sea; but there does seem to have been misjudgment in the direction given to the fleet. It was known that De Barras had sailed from Newport with eight ships, bound probably for the Chesapeake, certainly to effect a junction with De Grasse; and it has been judiciously pointed out that if Graves had taken up his cruising-ground near the Capes, but out of sight of land, he could hardly have failed to fall in with him in overwhelming force. Knowing what is now known, this would undoubtedly have been the proper thing to do; but the English admiral had imperfect information. It was nowhere expected that the French would bring nearly the force they did; and Graves lost information, which he ought to have received, as to their numbers, by the carelessness of his cruisers stationed off the Chesapeake. These had been ordered to keep under way, but were both at anchor under Cape Henry when De Grasse's appearance cut off their escape. One was captured, the other driven up York River. No single circumstance contributed more to the general result than the neglect of these two subordinate officers, by which Graves lost that all-important information. It can readily be conceived how his movements might have been affected, had he known two days earlier that De Grasse had brought twenty-seven or twenty-eight sail of the line; how natural would have been the conclusion, first, to waylay De Barras, with whom his own nineteen could more than cope. "Had Admiral Graves succeeded in capturing that squadron, it would have greatly paralyzed the besieging army [it had the siege train on board], if it would not have prevented its operations altogether; it would have put the two fleets nearly on an equality in point of numbers, would have arrested the progress of the French arms for the ensuing year in the West Indies, and might possibly have created such a spirit of discord between the French and Americans150 as would have sunk the latter into the lowest depths of despair, from which they were only extricated by the arrival of the forces under De Grasse."151 These are true and sober comments upon the naval strategy.

In regard to the admiral's tactics, it will be enough to say that the fleet was taken into battle nearly as Byng took his; that very similar mishaps resulted; and that, when attacking twenty-four ships with nineteen, seven, under that capable officer Hood, were not able to get into action, owing to the dispositions made.

On the French side De Grasse must be credited with a degree of energy, foresight, and determination surprising in view of his failures at other times. The decision to take every ship with him, which made him independent of any failure on the part of De Barras; the passage through the Bahama Channel to conceal his movements; the address with which he obtained the money and troops required, from the Spanish and the French military authorities; the prevision which led him, as early as March 29, shortly after leaving Brest, to write to Rochambeau that American coast pilots should be sent to Cap Français; the coolness with which he kept Graves amused until De Barras's squadron had slipped in, are all points worthy of admiration. The French were also helped by the admiral's power to detain the two hundred merchant-ships, the "West India trade," awaiting convoy at Cap Français, where they remained from July till November, when the close of operations left him at liberty to convoy them with ships-of-war. The incident illustrates one weakness of a mercantile country with representative government, compared with a purely military nation. "If the British government," wrote an officer of that day, "had sanctioned, or a British admiral had adopted, such a measure, the one would have been turned out and the other hanged."152 Rodney at the same time had felt it necessary to detach five ships-of-the-line with convoys, while half a dozen more went home with the trade from Jamaica.

It is easier to criticise the division of the English fleet between the West Indies and North America in the successive years 1780 and 1781, than to realize the embarrassment of the situation. This embarrassment was but the reflection of the military difficulty of England's position, all over the world, in this great and unequal war. England was everywhere outmatched and embarrassed, as she has always been as an empire, by the number of her exposed points. In Europe the Channel fleet was more than once driven into its ports by overwhelming forces. Gibraltar, closely blockaded by land and sea, was only kept alive in its desperate resistance by the skill of English seamen triumphing over the inaptness and discords of their combined enemies. In the East Indies, Sir Edward Hughes met in Suffren an opponent as superior to him in numbers as was De Grasse to Hood, and of far greater ability. Minorca, abandoned by the home government, fell before superior strength, as has been seen to fall, one by one, the less important of the English Antilles. The position of England from the time that France and Spain opened their maritime war was everywhere defensive, except in North America; and was therefore, from the military point of view, essentially false. She everywhere awaited attacks which the enemies, superior in every case, could make at their own choice and their own time. North America was really no exception to this rule, despite some offensive operations which in no way injured her real, that is her naval, foes.

Thus situated, and putting aside questions of national pride or sensitiveness, what did military wisdom prescribe to England? The question would afford an admirable study to a military inquirer, and is not to be answered off-hand, but certain evident truths may be pointed out. In the first place, it should have been determined what part of the assailed empire was most necessary to be preserved. After the British islands themselves, the North American colonies were the most valuable possessions in the eyes of the England of that day. Next should have been decided what others by their natural importance were best worth preserving, and by their own inherent strength, or that of the empire, which was mainly naval strength, could most surely be held. In the Mediterranean, for instance, Gibraltar and Mahon were both very valuable positions. Could both be held? Which was more easily to be reached and supported by the fleet? If both could not probably be held, one should have been frankly abandoned, and the force and efforts necessary to its defence carried elsewhere. So in the West Indies the evident strategic advantages of Barbadoes and Sta. Lucia prescribed the abandonment of the other small islands by garrisons as soon as the fleet was fairly outnumbered, if not before. The case of so large an island as Jamaica must be studied separately, as well as with reference to the general question. Such an island may be so far self-supporting as to defy any attack but one in great force and numbers, and that would rightly draw to it the whole English force from the windward stations at Barbadoes and Sta. Lucia.

With the defence thus concentrated, England's great weapon, the navy, should have been vigorously used on the offensive. Experience has taught that free nations, popular governments, will seldom dare wholly to remove the force that lies between an invader and its shores or capital. Whatever the military wisdom, therefore, of sending the Channel fleet to seek the enemy before it united, the step may not have been possible. But at points less vital the attack of the English should have anticipated that of the allies. This was most especially true of that theatre of the war which has so far been considered. If North America was the first object, Jamaica and the other islands should have been boldly risked. It is due to Rodney to say that he claims that his orders to the admirals at Jamaica and New York were disobeyed in 1781, and that to this was owing the inferiority in number of Graves's fleet.

But why, in 1780, when the departure of De Guichen for Europe left Rodney markedly superior in numbers during his short visit to North America, from September 14 to November 14, should no attempt have been made to destroy the French detachment of seven ships-of-the-line in Newport? These ships had arrived there in July; but although they had at once strengthened their position by earthworks, great alarm was excited by the news of Rodney's appearance off the coast. A fortnight passed by Rodney in New York and by the French in busy work, placed the latter, in their own opinion, in a position to brave all the naval force of England. "We twice feared, and above all at the time of Rodney's arrival," wrote the chief of staff of the French squadron, "that the English might attack us in the road itself; and there was a space of time during which such an undertaking would not have been an act of rashness. Now [October 20], the anchorage is fortified so that we can there brave all the naval force of England."153

The position thus taken by the French was undoubtedly very strong.154 It formed a re-entrant angle of a little over ninety degrees, contained by lines drawn from Goat Island to what was then called Brenton's Point, the site of the present Fort Adams on the one side, and to Rose Island on the other. On the right flank of the position Rose Island received a battery of thirty-six 24-pounders; while twelve guns of the same size were placed on the left flank at Brenton's Point. Between Rose and Goat islands four ships, drawn up on a west-northwest line, bore upon the entrance and raked an approaching fleet; while three others, between Goat Island and Brenton's Point, crossed their fire at right angles with the former four.

On the other hand, the summer winds blow directly up the entrance, often with great force. There could be no question even of a considerably crippled attacking ship reaching her destined position, and when once confused with the enemy's line, the shore batteries would be neutralized. The work on Rose Island certainly, that on Brenton's Point probably, had less height than the two upper batteries of a ship-of-the-line, and could be vastly outnumbered. They could not have been casemated, and might indisputably have been silenced by the grapeshot of the ships that could have been brought against them. Rose Island could be approached on the front and on the west flank within two hundred yards, and on the north within half a mile. There was nothing to prevent this right flank of the French, including the line of ships, being enfiladed and crushed by the English ships taking position west of Rose Island. The essential points of close range and superior height were thus possible to the English fleet, which numbered twenty to the enemy's seven. If successful in destroying the shipping and reducing Rose Island, it could find anchorage farther up the bay and await a favorable wind to retire. In the opinion of a distinguished English naval officer of the day,155 closely familiar with the ground, there was no doubt of the success of an attack; and he urged it frequently upon Rodney, offering himself to pilot the leading ship. The security felt by the French in this position, and the acquiescence of the English in that security, mark clearly the difference in spirit between this war and the wars of Nelson and Napoleon.