полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Putting entirely aside questions of international law, the wisdom and conduct of Suffren's attack, from the military point of view, invite attention. To judge them properly, we must consider what was the object of the mission with which he was charged, and what were the chief factors in thwarting or forwarding it. His first object was to protect the Cape of Good Hope against an English expedition; the chief reliance for effecting his purpose was to get there first; the obstacle to his success was the English fleet. To anticipate the arrival of the latter, two courses were open to him,—to run for it in the hope of winning the race, or to beat the enemy and so put him out of the running altogether. So long as his whereabouts was unknown, a search, unless with very probable information, would be a waste of time; but when fortune had thrown his enemy across his path, the genius of Suffren at once jumped to the conclusion that the control of the sea in southern waters would determine the question, and should be settled at once. To use his own strong expression, "The destruction of the English squadron would cut off the root of all the plans and projects of that expedition, gain us for a long time the superiority in India, a superiority whence might result a glorious peace, and hinder the English from reaching the Cape before me,—an object which has been fulfilled and was the principal aim of my mission." He was ill-informed as to the English force, believing it greater than it was; but he had it at disadvantage and surprised. The prompt decision to fight, therefore, was right, and it is the most pronounced merit of Suffren in this affair, that he postponed for the moment—dismissed, so to speak, from his mind—the ulterior projects of the cruise; but in so doing he departed from the traditions of the French navy and the usual policy of his government. It cannot be imputed to him as a fault that he did not receive from his captains the support he was fairly entitled to expect. The accidents and negligence which led to their failure have been mentioned; but having his three best ships in hand, there can be little doubt he was right in profiting by the surprise, and trusting that the two in reserve would come up in time.

The position taken by his own ship and by the "Hannibal," enabling them to use both broadsides,—in other words, to develop their utmost force,—was excellently judged. He thus availed himself to the full of the advantage given by the surprise and by the lack of order in the enemy's squadron. This lack of order, according to English accounts, threw out of action two of their fifty-gun ships,—a circumstance which, while discreditable to Johnstone, confirmed Suffren's judgment in precipitating his attack. Had he received the aid upon which, after all deductions, he was justified in counting, he would have destroyed the English squadron; as it was, he saved the Cape Colony at Porto Praya. It is not surprising, therefore, that the French Court, notwithstanding its traditional sea policy and the diplomatic embarrassment caused by the violation of Portuguese neutrality, should have heartily and generously acknowledged a vigor of action to which it was unused in its admirals.

It has been said that Suffren, who had watched the cautious movements of D'Estaing in America, and had served in the Seven Years' War, attributed in part the reverses suffered by the French at sea to the introduction of Tactics, which he stigmatized as the veil of timidity; but that the results of the fight at Porto Praya, necessarily engaged without previous arrangement, convinced him that system and method had their use.171 Certainly his tactical combinations afterward were of a high order, especially in his earlier actions in the East (for he seems again to have abandoned them in the later fights under the disappointment caused by his captains' disaffection or blundering). But his great and transcendent merit lay in the clearness with which he recognized in the English fleets, the exponent of the British sea power, the proper enemy of the French fleet, to be attacked first and always when with any show of equality. Far from blind to the importance of those ulterior objects to which the action of the French navy was so constantly subordinated, he yet saw plainly that the way to assure those objects was not by economizing his own ships, but by destroying those of the enemy. Attack, not defence, was the road to sea power in his eyes; and sea power meant control of the issues upon the land, at least in regions distant from Europe. This view out of the English policy he had the courage to take, after forty years of service in a navy sacrificed to the opposite system; but he brought to its practical application a method not to be found in any English admiral of the day, except perhaps Rodney, and a fire superior to the latter. Yet the course thus followed was no mere inspiration of the moment; it was the result of clear views previously held and expressed. However informed by natural ardor, it had the tenacity of an intellectual conviction. Thus he wrote to D'Estaing, after the failure to destroy Barrington's squadron at Sta. Lucia, remonstrating upon the half-manned condition of his own and other ships, from which men had been landed to attack the English troops:—

"Notwithstanding the small results of the two cannonades of the 15th of December [directed against Barrington's squadron], and the unhappy check our land forces have undergone, we may yet hope for success. But the only means to have it is to attack vigorously the squadron, which, with our superiority, cannot resist, notwithstanding its land batteries, whose effects will be neutralized if we run them aboard, or anchor upon their buoys. If we delay, they may escape.... Besides, our fleet being unmanned, it is in condition neither to sail nor to fight. What would happen if Admiral Byron's fleet should arrive? What would become of ships having neither crews nor admiral? Their defeat would cause the loss of the army and the colony. Let us destroy that squadron; their army, lacking everything and in a bad country, would soon be obliged to surrender. Then let Byron come, we shall be pleased to see him. I think it is not necessary to point out that for this attack we need men and plans well concerted with those who are to execute them."

Equally did he condemn the failure of D'Estaing to capture the four crippled ships of Byron's squadron, after the action off Grenada.

Owing to a combination of misfortunes, the attack at Porto Praya had not the decisive result it deserved. Commodore Johnstone got under way and followed Suffren; but he thought his force was not adequate to attack in face of the resolute bearing of the French, and feared the loss of time consequent upon chasing to leeward of his port. He succeeded, however, in retaking the East India ship which the "Artésien" had carried out. Suffren continued his course and anchored at the Cape, in Simon's Bay, on the 21st of June. Johnstone followed him a fortnight later; but learning by an advance ship that the French troops had been landed, he gave up the enterprise against the colony, made a successful commerce-destroying attack upon five Dutch India ships in Saldanha Bay, which poorly repaid the failure of the military undertaking, and then went back himself to England, after sending the ships-of-the-line on to join Sir Edward Hughes in the East Indies.

Having seen the Cape secured, Suffren sailed for the Isle of France, arriving there on the 25th of October, 1781. Count d'Orves, being senior, took command of the united squadron. The necessary repairs were made, and the fleet sailed for India, December 17. On the 22d of January, 1782, an English fifty-gun ship, the "Hannibal," was taken. On the 9th of February Count d'Orves died, and Suffren became commander-in-chief, with the rank of commodore. A few days later the land was seen to the northward of Madras; but owing to head-winds the city was not sighted until February 15. Nine large ships-of-war were found anchored in order under the guns of the forts. They were the fleet of Sir Edward Hughes, not in confusion like that of Johnstone.172

Here, at the meeting point between these two redoubtable champions, each curiously representative of the characteristics of his own race,—the one of the stubborn tenacity and seamanship of the English, the other of the ardor and tactical science of the French, too long checked and betrayed by a false system,—is the place to give an accurate statement of the material forces. The French fleet had three seventy-fours, seven sixty-fours, and two fifty-gun ships, one of which was the lately captured English "Hannibal." To these Sir Edward Hughes opposed two seventy-fours, one seventy, one sixty-eight, four sixty-fours, and one fifty-gun ship. The odds, therefore, twelve to nine, were decidedly against the English; and it is likely that the advantage in single-ship power, class for class, was also against them.

It must be recalled that at the time of his arrival Suffren found no friendly port or roadstead, no base of supplies or repair. The French posts had all fallen by 1779; and his rapid movement, which saved the Cape, did not bring him up in time to prevent the capture of the Dutch Indian possessions. The invaluable harbor of Trincomalee, in Ceylon, was taken just one month before Suffren saw the English fleet at Madras. But if he thus had everything to gain, Hughes had as much to lose. To Suffren, at the moment of first meeting, belonged superiority of numbers and the power of taking the offensive, with all its advantages in choice of initiative. Upon Hughes fell the anxiety of the defensive, with inferior numbers, many assailable points, and uncertainty as to the place where the blow would fall.

It was still true, though not so absolutely as thirty years before, that control in India depended upon control of the sea. The passing years had greatly strengthened the grip of England, and proportionately loosened that of France. Relatively, therefore, the need of Suffren to destroy his enemy was greater than that of his predecessors, D'Aché and others; whereas Hughes could count upon a greater strength in the English possessions, and so bore a somewhat less responsibility than the admirals who went before him.

Nevertheless, the sea was still by far the most important factor in the coming strife, and for its proper control it was necessary to disable more or less completely the enemy's fleet, and to have some reasonably secure base. For the latter purpose, Trincomalee, though unhealthy, was by far the best harbor on the east coast; but it had not been long enough in the hands of England to be well supplied. Hughes, therefore, inevitably fell back on Madras for repairs after an action, and was forced to leave Trincomalee to its own resources until ready to take the sea again. Suffren, on the other hand, found all ports alike destitute of naval supplies, while the natural advantages of Trincomalee made its possession an evident object of importance to him; and Hughes so understood it.

Independently, therefore, of the tradition of the English navy impelling Hughes to attack, the influence of which appears plainly between the lines of his letters, Suffren had, in moving toward Trincomalee, a threat which was bound to draw his adversary out of his port. Nor did Trincomalee stand alone; the existing war between Hyder Ali and the English made it imperative for Suffren to seize a port upon the mainland, at which to land the three thousand troops carried by the squadron to co-operate on shore against the common enemy, and from which supplies, at least of food, might be had. Everything, therefore, concurred to draw Hughes out, and make him seek to cripple or hinder the French fleet.

The method of his action would depend upon his own and his adversary's skill, and upon the uncertain element of the weather. It was plainly desirable for him not to be brought to battle except on his own terms; in other words, without some advantage of situation to make up for his weaker force. As a fleet upon the open sea cannot secure any advantages of ground, the position favoring the weaker was that to windward, giving choice of time and some choice as to method of attack, the offensive position used defensively, with the intention to make an offensive movement if circumstances warrant. The leeward position left the weaker no choice but to run, or to accept action on its adversary's terms.

Whatever may be thought of Hughes's skill, it must be conceded that his task was difficult. Still, it can be clearly thought down to two requisites. The first was to get in a blow at the French fleet, so as to reduce the present inequality; the second, to keep Suffren from getting Trincomalee, which depended wholly on the fleet.173 Suffren, on the other hand, if he could do Hughes, in an action, more injury than he himself received, would be free to turn in any direction he chose.

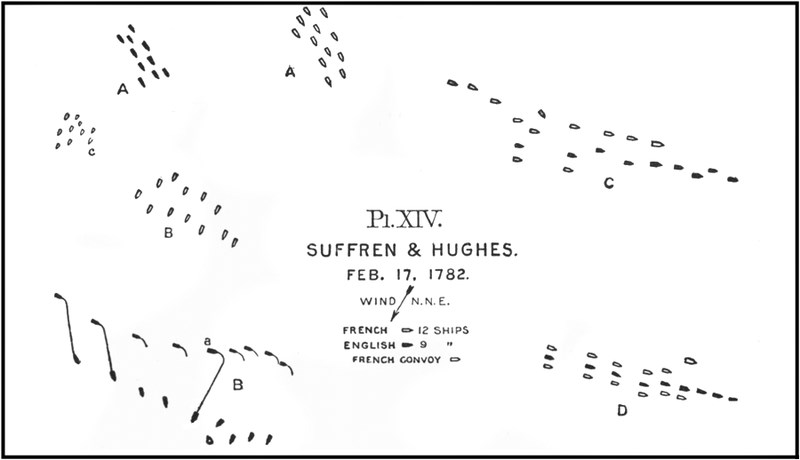

Suffren having sighted Hughes's fleet at Madras, February 15, anchored his own four miles to the northward. Considering the enemy's line, supported by the batteries, to be too strong for attack, he again got under way at four P.M., and stood south. Hughes also weighed, standing to the southward all that night under easy sail, and at daylight found that the enemy's squadron had separated from the convoy, the ships of war being about twelve miles east, while the transports were nine miles southwest, from him (Plate XIV. A, A). This dispersal is said to have been due to the carelessness of the French frigates, which did not keep touch of the English. Hughes at once profited by it, chasing the convoy (c), knowing that the line-of-battle ships must follow. His copper-bottomed ships came up with and captured six of the enemy, five of which were English prizes. The sixth carried three hundred troops with military stores. Hughes had scored a point.

Suffren of course followed in a general chase, and by three P.M. four of his best sailers were two or three miles from the sternmost English ships. Hughes's ships were now much scattered, but not injudiciously so, for they joined by signal at seven P.M. Both squadrons stood to the southeast during the night, under easy sail.

At daylight of the 17th—the date of the first of four actions fought between these two chiefs within seven months—the fleets were six or eight miles apart, the French bearing north-northeast from the English (B, B). The latter formed line-ahead on the port tack (a), with difficulty, owing to the light winds and frequent calms. Admiral Hughes explains that he hoped to weather the enemy by this course so as to engage closely, counting probably on finding himself to windward when the sea-breeze made. The wind continuing light, but with frequent squalls, from north-northeast, the French, running before it, kept the puffs longer and neared the English rapidly, Suffren's intention to attack the rear being aided by Hughes's course. The latter finding his rear straggling, bore up to line abreast (b), retreating to gain time for the ships to close on the centre. These movements in line abreast continued till twenty minutes before four P.M., when, finding he could not escape attack on the enemy's terms, Hughes hauled his wind on the port tack and awaited it (C). Whether by his own fault or not, he was now in the worst possible position, waiting for an attack by a superior force at its pleasure. The rear ship of his line, the "Exeter," was not closed up; and there appears no reason why she should not have been made the van, by forming on the starboard tack, and thus bringing the other ships up to her.

Pl. XIV.

The method of Suffren's attack (C) is differently stated by him and by Hughes, but the difference is in detail only; the main facts are certain. Hughes says the enemy "steered down on the rear of our line in an irregular double line-abreast," in which formation they continued till the moment of collision, when "three of the enemy's ships in the first line bore right down upon the 'Exeter,' while four more of their second line, headed by the 'Héros,' in which M. de Suffren had his flag, hauled along the outside of the first line toward our centre. At five minutes past four the enemy's three ships began their fire upon the 'Exeter,' which was returned by her and her second ahead; the action became general from our rear to our centre, the commanding ship of the enemy, with three others of their second line, leading down on our centre, yet never advancing farther than opposite to the 'Superbe,' our centre ship, with little or no wind and some heavy rain during the engagement. Under these circumstances, the enemy brought eight of their best ships to the attack of five of ours, as the van of our line, consisting of the 'Monmouth,' 'Eagle,' 'Burford,' and 'Worcester,' could not be brought into action without tacking on the enemy," for which there was not enough wind.

Here we will leave them, and give Suffren's account of how he took up his position. In his report to the Minister of Marine he says:—

"I should have destroyed the English squadron, less by superior numbers than by the advantageous disposition in which I attacked it. I attacked the rear ship and stood along the English line as far as the sixth. I thus made three of them useless, so that we were twelve against six. I began the fight at half-past three in the afternoon, taking the lead and making signal to form line as best could be done; without that I would not have engaged. At four I made signal to three ships to double on the enemy's rear, and to the squadron to approach within pistol-shot. This signal, though repeated, was not executed. I did not myself give the example, in order that I might hold in check the three van ships, which by tacking would have doubled on me. However, except the 'Brilliant,' which doubled on the rear, no ship was as close as mine, nor received as many shots."

The principal point of difference in the two accounts is, that Suffren asserts that his flag-ship passed along the whole English line, from the rear to the sixth ship; while Hughes says the French divided into two lines, which, upon coming near, steered, one on the rear, the other on the centre, of his squadron. The latter would be the better manœuvre; for if the leading ship of the attack passed, as Suffren asserts, along the enemy's line from the rear to the sixth, she should receive in succession the first fire of six ships, which ought to cripple her and confuse her line. Suffren also notes the intention to double on the rear by placing three ships to leeward of it. Two of the French did take this position. Suffren further gives his reason for not closing with his own ship, which led; but as those which followed him went no nearer, Hughes's attention was not drawn to his action.

The French commodore was seriously, and it would seem justly, angered by the inaction of several of his captains. Of the second in command he complained to the minister: "Being at the head, I could not well see what was going on in the rear. I had directed M. de Tromelin to make signals to ships which might be near him; he only repeated my own without having them carried out." This complaint was wholly justified. On the 6th of February, ten days before the fight, he had written to his second as follows:—

"If we are so fortunate as to be to windward, as the English are not more than eight, or at most nine, my intention is to double on their rear. Supposing your division to be in the rear, you will see by your position what number of ships will overlap the enemy's line, and you will make signal to them to double174 [that is, to engage on the lee side].... In any case, I beg you to order to your division the manœuvres which you shall think best fitted to assure the success of the action. The capture of Trincomalee and that of Negapatam, and perhaps of all Ceylon, should make us wish for a general action."

The last two sentences reveal Suffren's own appreciation of the military situation in the Indian seas, which demanded, first, the disabling of the hostile fleet, next, the capture of certain strategic ports. That this diagnosis was correct is as certain as that it reversed the common French maxims, which would have put the port first and the fleet second as objectives. A general action was the first desideratum of Suffren, and it is therefore safe to say that to avoid such action should have been the first object of Hughes. The attempt of the latter to gain the windward position was consequently correct; and as in the month of February the sea-breeze at Madras sets in from the eastward and southward about eleven A.M., he probably did well to steer in that general direction, though the result disappointed him. De Guichen in one of his engagements with Rodney shaped the course of his fleet with reference to being to windward when the afternoon breeze made, and was successful. What use Hughes would have made of the advantage of the wind can only be inferred from his own words,—that he sought it in order to engage more closely. There is not in this the certain promise of any skilful use of a tactical advantage.

Suffren also illustrates, in his words to Tromelin, his conception of the duties of a second in command, which may fairly be paralleled with that of Nelson in his celebrated order before Trafalgar. In this first action he led the main attack himself, leaving the direction of what may be called the reserve—at any rate, of the second half of the assault—to his lieutenant, who, unluckily for him, was not a Collingwood, and utterly failed to support him. It is probable that Suffren's leading was due not to any particular theory, but to the fact that his ship was the best sailer in the fleet, and that the lateness of the hour and lightness of the wind made it necessary to bring the enemy to action speedily. But here appears a fault on the part of Suffren. Leading as he did involves, not necessarily but very naturally, the idea of example; and holding his own ship outside of close range, for excellent tactical reasons, led the captains in his wake naturally, almost excusably, to keep at the same distance, notwithstanding his signals. The conflict between orders and example, which cropped out so singularly at Vicksburg in our civil war, causing the misunderstanding and estrangement of two gallant officers, should not be permitted to occur. It is the business of a chief to provide against such misapprehensions by most careful previous explanation of both the letter and spirit of his plans. Especially is this so at sea, where smoke, slack wind, and intervening rigging make signals hard to read, though they are almost the only means of communication. This was Nelson's practice; nor was Suffren a stranger to the idea. "Dispositions well concerted with those who are to carry them out are needed," he wrote to D'Estaing, three years before. The excuse which may be pleaded for those who followed him, and engaged, cannot avail for the rear ships, and especially not for the second in command, who knew Suffren's plans. He should have compelled the rear ships to take position to leeward, leading himself, if necessary. There was wind enough; for two captains actually engaged to leeward, one of them without orders, acting, through the impulse of his own good will and courage, on Nelson's saying, "No captain can do very wrong who places his ship alongside that of an enemy." He received the special commendation of Suffren, in itself an honor and a reward. Whether the failure of so many of his fellows was due to inefficiency, or to a spirit of faction and disloyalty, is unimportant to the general military writer, however interesting to French officers jealous for the honor of their service. Suffren's complaints, after several disappointments, became vehement.

"My heart," wrote he, "is wrung by the most general defection. I have just lost the opportunity of destroying the English squadron.... All—yes, all—might have got near, since we were to windward and ahead, and none did so. Several among them had behaved bravely in other combats. I can only attribute this horror to the wish to bring the cruise to an end, to ill-will, and to ignorance; for I dare not suspect anything worse. The result has been terrible. I must tell you, Monseigneur, that officers who have been long at the Isle of France are neither seamen nor military men. Not seamen, for they have not been at sea; and the trading temper, independent and insubordinate, is absolutely opposed to the military spirit."

This letter, written after his fourth battle with Hughes, must be taken with allowance. Not only does it appear that Suffren himself, hurried away on this last occasion by his eagerness, was partly responsible for the disorder of his fleet, but there were other circumstances, and above all the character of some of the officers blamed, which made the charge of a general disaffection excessive. On the other hand, it remains true that after four general actions, with superior numbers on the part of the French, under a chief of the skill and ardor of Suffren, the English squadron, to use his own plaintive expression, "still existed;" not only so, but had not lost a single ship. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that of a French naval writer: "Quantity disappeared before quality."175 It is immaterial whether the defect was due to inefficiency or disaffection.