полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Another cause than incapacity as a seaman has usually been assigned by French historians for the impotent action of D'Estaing on this occasion. He looked upon Grenada, they say, as the real objective of his efforts, and considered the English fleet a very secondary concern. Ramatuelle, a naval tactician who served actively in this war and wrote under the Empire, cites this case, which he couples with that of Yorktown and others, as exemplifying the true policy of naval war. His words, which probably reflect the current opinion of his service in that day, as they certainly do the policy of French governments, call for more than passing mention, as they involve principles worthy of most serious discussion:—

"The French navy has always preferred the glory of assuring or preserving a conquest to that, more brilliant perhaps, but actually less real, of taking a few ships; and in that it has approached more nearly the true end to be proposed in war. What in fact would the loss of a few ships matter to the English? The essential point is to attack them in their possessions, the immediate source of their commercial wealth and of their maritime power. The war of 1778 furnishes examples which prove the devotion of the French admirals to the true interests of the country. The preservation of the island of Grenada, the reduction of Yorktown where the English army surrendered, the conquest of the island of St. Christopher, were the result of great battles in which the enemy was allowed to retreat undisturbed, rather than risk giving him a chance to succor the points attacked."

The issue could not be more squarely raised than in the case of Grenada. No one will deny that there are moments when a probable military success is to be foregone, or postponed, in favor of one greater or more decisive. The position of De Grasse at the Chesapeake, in 1781, with the fate of Yorktown hanging in the balance, is in point; and it is here coupled with that of D'Estaing at Grenada, as though both stood on the same grounds. Both are justified alike; not on their respective merits as fitting the particular cases, but upon a general principle. Is that principle sound? The bias of the writer quoted betrays itself unconsciously, in saying "a few ships." A whole navy is not usually to be crushed at a blow; a few ships mean an ordinary naval victory. In Rodney's famous battle only five ships were taken, though Jamaica was saved thereby.

In order to determine the soundness of the principle, which is claimed as being illustrated by these two cases (St. Christopher will be discussed later on), it is necessary to examine what was the advantage sought, and what the determining factor of success in either case. At Yorktown the advantage sought was the capture of Cornwallis's army; the objective was the destruction of the enemy's organized military force on shore. At Grenada the chosen objective was the possession of a piece of territory of no great military value; for it must be remarked that all these smaller Antilles, if held in force at all, multiplied large detachments, whose mutual support depended wholly upon the navy. These large detachments were liable to be crushed separately, if not supported by the navy; and if naval superiority is to be maintained, the enemy's navy must be crushed. Grenada, near and to leeward of Barbadoes and Sta. Lucia, both held strongly by the English, was peculiarly weak to the French; but sound military policy for all these islands demanded one or two strongly fortified and garrisoned naval bases, and dependence for the rest upon the fleet. Beyond this, security against attacks by single cruisers and privateers alone was needed.

Such were the objectives in dispute. What was the determining factor in this strife? Surely the navy, the organized military force afloat. Cornwallis's fate depended absolutely upon the sea. It is useless to speculate upon the result, had the odds on the 5th of September, 1781, in favor of De Grasse, been reversed; if the French, instead of five ships more, had had five ships less than the English. As it was, De Grasse, when that fight began, had a superiority over the English equal to the result of a hard-won fight. The question then was, should he risk the almost certain decisive victory over the organized enemy's force ashore, for the sake of a much more doubtful advantage over the organized force afloat? This was not a question of Yorktown, but of Cornwallis and his army; there is a great deal in the way things are put.

So stated,—and the statement needs no modifications,—there can be but one answer. Let it be remarked clearly, however, that both De Grasse's alternatives brought before him the organized forces as the objective.

Not so with D'Estaing at Grenada. His superiority in numbers over the English was nearly as great as that of De Grasse; his alternative objectives were the organized force afloat and a small island, fertile, but militarily unimportant. Grenada is said to have been a strong position for defence; but intrinsic strength does not give importance, if the position has not strategic value. To save the island, he refused to use an enormous advantage fortune had given him over the fleet. Yet upon the strife between the two navies depended the tenure of the islands. Seriously to hold the West India Islands required, first, a powerful seaport, which the French had; second, the control of the sea. For the latter it was necessary, not to multiply detachments in the islands, but to destroy the enemy's navy, which may be accurately called the army in the field. The islands were but rich towns; and not more than one or two fortified towns, or posts, were needed.

It may safely be said that the principle which led to D'Estaing's action was not, to say the least, unqualifiedly correct; for it led him wrong. In the case of Yorktown, the principle as stated by Ramatuelle is not the justifying reason of De Grasse's conduct, though it likely enough was the real reason. What justified De Grasse was that, the event depending upon the unshaken control of the sea, for a short time only, he already had it by his greater numbers. Had the numbers been equal, loyalty to the military duty of the hour must have forced him to fight, to stop the attempt which the English admiral would certainly have made. The destruction of a few ships, as Ramatuelle slightingly puts it, gives just that superiority to which the happy result at Yorktown was due. As a general principle, this is undoubtedly a better objective than that pursued by the French. Of course, exceptions will be found; but those exceptions will probably be where, as at Yorktown, the military force is struck at directly elsewhere, or, as at Port Mahon, a desirable and powerful base of that force is at stake; though even at Mahon it is doubtful whether the prudence was not misplaced. Had Hawke or Boscawen met with Byng's disaster, they would not have gone to Gibraltar to repair it, unless the French admiral had followed up his first blow with others, increasing their disability.

Grenada was no doubt very dear in the eyes of D'Estaing, because it was his only success. After making the failures at the Delaware, at New York, and at Rhode Island, with the mortifying affair at Sta. Lucia, it is difficult to understand the confidence in him expressed by some French writers. Gifted with a brilliant and contagious personal daring, he distinguished himself most highly, when an admiral, by leading in person assaults upon intrenchments at Sta. Lucia and Grenada, and a few months later in the unsuccessful attack upon Savannah.

During the absence of the French navy in the winter of 1778-79, the English, controlling now the sea with a few of their ships that had not gone to the West Indies, determined to shift the scene of the continental war to the Southern States, where there was believed to be a large number of loyalists. The expedition was directed upon Georgia, and was so far successful that Savannah fell into their hands in the last days of 1778. The whole State speedily submitted. Operations were thence extended into South Carolina, but failed to bring about the capture of Charleston.

Word of these events was sent to D'Estaing in the West Indies, accompanied by urgent representations of the danger to the Carolinas, and the murmurings of the people against the French, who were accused of forsaking their allies, having rendered them no service, but on the contrary having profited by the cordial help of the Bostonians to refit their crippled fleet. There was a sting of truth in the alleged failure to help, which impelled D'Estaing to disregard the orders actually in his hands to return at once to Europe with certain ships. Instead of obeying them he sailed for the American coast with twenty-two ships-of-the-line, having in view two objects,—the relief of the Southern States and an attack upon New York in conjunction with Washington's army.

Arriving off the coast of Georgia on the 1st of September, D'Estaing took the English wholly at unawares; but the fatal lack of promptness, which had previously marked the command of this very daring man, again betrayed his good fortune. Dallying at first before Savannah, the fleeting of precious days again brought on a change of conditions, and the approach of the bad-weather season impelled him, too slow at first, into a premature assault. In it he displayed his accustomed gallantry, fighting at the head of his column, as did the American general; but the result was a bloody repulse. The siege was raised, and D'Estaing sailed at once for France, not only giving up his project upon New York, but abandoning the Southern States to the enemy. The value of this help from the great sea power of France, thus cruelly dangled before the eyes of the Americans only to be withdrawn, was shown by the action of the English, who abandoned Newport in the utmost haste when they learned the presence of the French fleet. Withdrawal had been before decided upon, but D'Estaing's coming converted it into flight.

After the departure of D'Estaing, which involved that of the whole French fleet,—for the ships which did not go back to France returned to the West Indies,—the English resumed the attack upon the Southern States, which had for a moment been suspended. The fleet and army left New York for Georgia in the last weeks of 1779, and after assembling at Tybee, moved upon Charleston by way of Edisto. The powerlessness of the Americans upon the sea left this movement unembarrassed save by single cruisers, which picked up some stragglers,—affording another lesson of the petty results of a merely cruising warfare. The siege of Charleston began at the end of March,—the English ships soon after passing the bar and Fort Moultrie without serious damage, and anchoring within gunshot of the place. Fort Moultrie was soon and easily reduced by land approaches, and the city itself was surrendered on the 12th of May, after a siege of forty days. The whole State was then quickly overrun and brought into military subjection.

The fragments of D'Estaing's late fleet were joined by a reinforcement from France under the Comte de Guichen, who assumed chief command in the West Indian seas March 22, 1780. The next day he sailed for Sta. Lucia, which he hoped to find unprepared; but a crusty, hard-fighting old admiral of the traditional English type, Sir Hyde Parker, had so settled himself at the anchorage, with sixteen ships, that Guichen with his twenty-two would not attack. The opportunity, if it were one, did not recur. De Guichen, returning to Martinique, anchored there on the 27th; and the same day Parker at Sta. Lucia was joined by the new English commander-in-chief, Rodney.

This since celebrated, but then only distinguished, admiral was sixty-two years old at the time of assuming a command where he was to win an undying fame. Of distinguished courage and professional skill, but with extravagant if not irregular habits, money embarrassments had detained him in exile in France at the time the war began. A boast of his ability to deal with the French fleet, if circumstances enabled him to go back to England, led a French nobleman who heard it to assume his debts, moved by feelings in which chivalry and national pique probably bore equal shares. Upon his return he was given a command, and sailed, in January, 1780, with a fleet of twenty ships-of-the-line, to relieve Gibraltar, then closely invested. Off Cadiz, with a good luck for which he was proverbial, he fell in with a Spanish fleet of eleven ships-of-the-line, which awkwardly held their ground until too late to fly.139 Throwing out the signal for a general chase, and cutting in to leeward of the enemy, between them and their port, Rodney, despite a dark and stormy night, succeeded in blowing up one ship and taking six. Hastening on, he relieved Gibraltar, placing it out of all danger from want; and then, leaving the prizes and the bulk of his fleet, sailed with the rest for his station.

Despite his brilliant personal courage and professional skill, which in the matter of tactics was far in advance of his contemporaries in England, Rodney, as a commander-in-chief, belongs rather to the wary, cautious school of the French tacticians than to the impetuous, unbounded eagerness of Nelson. As in Tourville we have seen the desperate fighting of the seventeenth century, unwilling to leave its enemy, merging into the formal, artificial—we may almost say trifling—parade tactics of the eighteenth, so in Rodney we shall see the transition from those ceremonious duels to an action which, while skilful in conception, aimed at serious results. For it would be unjust to Rodney to press the comparison to the French admirals of his day. With a skill that De Guichen recognized as soon as they crossed swords, Rodney meant mischief, not idle flourishes. Whatever incidental favors fortune might bestow by the way, the objective from which his eye never wandered was the French fleet,—the organized military force of the enemy on the sea. And on the day when Fortune forsook the opponent who had neglected her offers, when the conqueror of Cornwallis failed to strike while he had Rodney at a disadvantage, the latter won a victory which redeemed England from the depths of anxiety, and restored to her by one blow all those islands which the cautious tactics of the allies had for a moment gained, save only Tobago.

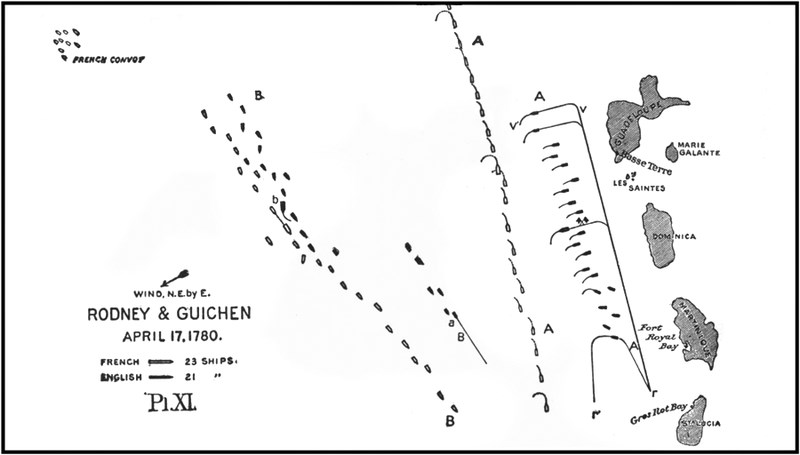

De Guichen and Rodney met for the first time on the 17th of April, 1780, three weeks after the arrival of the latter. The French fleet was beating to windward in the Channel between Martinique and Dominica, when the enemy was made in the southeast. A day was spent in manœuvring for the weather-gage, which Rodney got. The two fleets being now well to leeward of the islands140 (Plate XI.), both on the starboard tack heading to the northward and the French on the lee bow of the English, Rodney, who was carrying a press of sail, signalled to his fleet that he meant to attack the enemy's rear and centre with his whole force; and when he had reached the position he thought suitable, ordered them to keep away eight points (90°) together (A, A, A). De Guichen, seeing the danger of the rear, wore his fleet all together and stood down to succor it. Rodney, finding himself foiled, hauled up again on the same tack as the enemy, both fleets now heading to the southward and eastward.141 Later, he again made signal for battle, followed an hour after, just at noon, by the order (quoting his own despatch), "for every ship to bear down and steer for her opposite in the enemy's line." This, which sounds like the old story of ship to ship, Rodney explains to have meant her opposite at the moment, not her opposite in numerical order. His own words are: "In a slanting position, that my leading ships might attack the van ships of the enemy's centre division, and the whole British fleet be opposed to only two thirds of the enemy" (B, B). The difficulty and misunderstanding which followed seem to have sprung mainly from the defective character of the signal book. Instead of doing as the admiral wished, the leading ships (a) carried sail so as to reach their supposed station abreast their numerical opposite in the order. Rodney stated afterward that when he bore down the second time, the French fleet was in a very extended line of battle; and that, had his orders been obeyed, the centre and rear must have been disabled before the van could have joined.

Pl. XI.

There seems every reason to believe that Rodney's intentions throughout were to double on the French, as asserted. The failure sprang from the signal-book and tactical inefficiency of the fleet; for which he, having lately joined, was not answerable. But the ugliness of his fence was so apparent to De Guichen, that he exclaimed, when the English fleet kept away the first time, that six or seven of his ships were gone; and sent word to Rodney that if his signals had been obeyed he would have had him for his prisoner.142 A more convincing proof that he recognized the dangerousness of his enemy is to be found in the fact that he took care not to have the lee-gage in their subsequent encounters. Rodney's careful plans being upset, he showed that with them he carried all the stubborn courage of the most downright fighter; taking his own ship close to the enemy and ceasing only when the latter hauled off, her foremast and mainyard gone, and her hull so damaged that she could hardly be kept afloat.

An incident of this battle mentioned by French writers and by Botta,143 who probably drew upon French authorities, but not found in the English accounts, shows the critical nature of the attack in the apprehension of the French. According to them, Rodney, marking a gap in their order due to a ship in rear of the French admiral being out of station, tried to break through (b); but the captain of the "Destin," seventy-four, pressed up under more sail and threw himself across the path of the English ninety-gun ship.

"The action of the 'Destin' was justly praised," says Lapeyrouse-Bonfils. "The fleet ran the danger of almost certain defeat, but for the bravery of M. de Goimpy. Such, after the affair, was the opinion of the whole French squadron. Yet, admitting that our line was broken, what disasters then would necessarily threaten the fleet? Would it not always have been easy for our rear to remedy the accident by promptly standing on to fill the place of the vessels cut off? That movement would necessarily have brought about a mêlée, which would have turned to the advantage of the fleet having the bravest and most devoted captains. But then, as under the empire, it was an acknowledged principle that ships cut off were ships taken, and the belief wrought its own fulfilment."

The effect of breaking an enemy's line, or order-of-battle, depends upon several conditions. The essential idea is to divide the opposing force by penetrating through an interval found, or made, in it, and then to concentrate upon that one of the fractions which can be least easily helped by the other. In a column of ships this will usually be the rear. The compactness of the order attacked, the number of the ships cut off, the length of time during which they can be isolated and outnumbered, will all affect the results. A very great factor in the issue will be the moral effect, the confusion introduced into a line thus broken. Ships coming up toward the break are stopped, the rear doubles up, while the ships ahead continue their course. Such a moment is critical, and calls for instant action; but the men are rare who in an unforeseen emergency can see, and at once take the right course, especially if, being subordinates, they incur responsibility. In such a scene of confusion the English, without presumption, hoped to profit by their better seamanship; for it is not only "courage and devotion," but skill, which then tells. All these effects of "breaking the line" received illustration in Rodney's great battle in 1782.

De Guichen and Rodney met twice again in the following month, but on neither occasion did the French admiral take the favorite lee-gage of his nation. Meanwhile a Spanish fleet of twelve ships-of-the-line was on its way to join the French. Rodney cruised to windward of Martinique to intercept them; but the Spanish admiral kept a northerly course, sighted Guadeloupe, and thence sent a despatch to De Guichen, who joined his allies and escorted them into port. The great preponderance of the coalition, in numbers, raised the fears of the English islands; but lack of harmony led to delays and hesitations, a terrible epidemic raged in the Spanish squadron, and the intended operations came to nothing. In August De Guichen sailed for France with fifteen ships. Rodney, ignorant of his destination, and anxious about both North America and Jamaica, divided his fleet, leaving one half in the islands, and with the remainder sailing for New York, where he arrived on the 12th of September. The risk thus run was very great, and scarcely justifiable; but no ill effect followed the dispersal of forces.144 Had De Guichen intended to turn upon Jamaica, or, as was expected by Washington, upon New York, neither part of Rodney's fleet could well have withstood him. Two chances of disaster, instead of one, were run, by being in small force on two fields instead of in full force on one.

Rodney's anxiety about North America was well grounded. On the 12th of July of this year the long expected French succor arrived,—five thousand French troops under Rochambeau and seven ships-of-the-line under De Ternay. Hence the English, though still superior at sea, felt forced to concentrate at New York, and were unable to strengthen their operations in Carolina. The difficulty and distance of movements by land gave such an advantage to sea power that Lafayette urged the French government further to increase the fleet; but it was still naturally and properly attentive to its own immediate interests in the Antilles. It was not yet time to deliver America.

Rodney, having escaped the great hurricane of October, 1780, by his absence, returned to the West Indies later in the year, and soon after heard of the war between England and Holland; which, proceeding from causes which will be mentioned later, was declared December 20, 1780. The admiral at once seized the Dutch islands of St. Eustatius and St. Martin, besides numerous merchant-ships, with property amounting in all to fifteen million dollars. These islands, while still neutral, had played a rôle similar to that of Nassau during the American Civil War, and had become a great depot of contraband goods, immense quantities of which now fell into the English hands.

The year 1780 had been gloomy for the cause of the United States. The battle of Camden had seemed to settle the English yoke on South Carolina, and the enemy formed high hopes of controlling both North Carolina and Virginia. The treason of Arnold following had increased the depression, which was but partially relieved by the victory at King's Mountain. The substantial aid of French troops was the most cheerful spot in the situation. Yet even that had a checkered light, the second division of the intended help being blocked in Brest by the English fleet; while the final failure of De Guichen to appear, and Rodney coming in his stead, made the hopes of the campaign fruitless.

A period of vehement and decisive action was, however, at hand. At the end of March, 1781, the Comte de Grasse sailed from Brest with twenty-six ships-of-the-line and a large convoy. When off the Azores, five ships parted company for the East Indies, under Suffren, of whom more will be heard later on. De Grasse came in sight of Martinique on the 28th of April. Admiral Hood (Rodney having remained behind at St. Eustatius) was blockading before Fort Royal, the French port and arsenal on the lee side of the island, in which were four ships-of-the-line, when his lookouts reported the enemy's fleet. Hood had two objects before him,—one to prevent the junction of the four blockaded ships with the approaching fleet, the other to keep the latter from getting between him and Gros Ilot Bay in Sta. Lucia. Instead of effecting this in the next twenty-four hours, by beating to windward of the Diamond Rock, his fleet got so far to leeward that De Grasse, passing through the channel on the 29th, headed up for Fort Royal, keeping his convoy between the fleet and the island. For this false position Hood was severely blamed by Rodney, but it may have been due to light winds and the lee current. However that be, the four ships in Fort Royal got under way and joined the main body. The English had now only eighteen ships to the French twenty-four, and the latter were to windward; but though thus in the proportion of four to three, and having the power to attack, De Grasse would not do it. The fear of exposing his convoy prevented him from running the chance of a serious engagement. Great must have been his distrust of his forces, one would say. When is a navy to fight, if this was not a time? He carried on a distant cannonade, with results so far against the English as to make his backwardness yet more extraordinary. Can a policy or a tradition which justifies such a line of conduct be good?