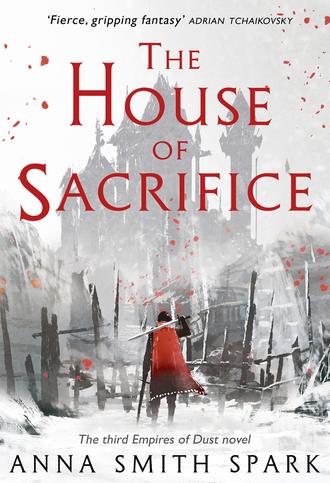

Полная версия

The House of Sacrifice

‘He?’

She blinked. ‘Our son.’

‘You know? How can you know?’ I don’t want it to be a boy, he found he was thinking, not a boy, not another murderer, parricide, dead thing, rot thing like I am. Will it kill her, tearing itself out of her? Cut her up into shreds, laugh in her face, curse her, take her heart to pieces slowly over years and years? I don’t want a child. I don’t want a boy. I want it to die like the rest, before it can harm her or I can harm it. It struck him suddenly: it is not dangerous for the mother to lose a child in the first early months.

She said, ‘I … Of course I don’t know.’

Did I kill them? he thought. The other children? Kill them in her, will them dead, give her poison in her sleep? I cannot father a living child. One of your generals himself plots to destroy you! Conspires against you! What if one of them is poisoning her, killing our children?

‘Why do you call it “he”, then? As though you think it will live, as though you pretend it will live?’ A wound, a rotting wound inside her already infected and dead.

‘He will live.’ Her hands clutched over her belly, tight, so tight like she might crush it, smother it in the womb. She was lying, they both knew it, it would die soon, any day, any moment, like the rest, just let it live let it live.

‘Don’t call it “he”.’

‘I – I want—’ And it came to him sick and horrified that she did not want it to be a girl. Look at her, the former High Priestess of the Great Temple, sacred holy beloved chosen of god who was born and raised to kill children, men dreaming in hot sweat about her hands stabbing them. She doesn’t want to have a daughter any more than I want to have a son. A perfect clarity, as he coughed the black sand of human bodies from his lungs: we both want this child more than all we have in the world, the last hopeful thing left to us, the only reason for anything. A child, to build an empire for. A child, to show our happiness and love. And we both want it to die unborn.

He remembered, so clearly, kissing Ti’s pink screwed-up face, kissing Ti’s pink flailing fist.

‘He will live,’ Thalia said again. ‘We should not be talking about this, Marith. Not now. You’re frightened, angry,’ she said. ‘You need to calm, to sleep.’

‘I saw …’ I can’t tell you, he thought, not you, I can’t speak it, I can’t have the child, my son, he can’t hear. Black sand crunched between his teeth.

Chapter Eight

It was a nightmare brought on by drink and stupid songs, he thought the next morning. There had been grains of black sand in the bed, he had woken to feel them itching him. A scalding hot bath; he drank and spat water, drank and spat, drank and spat. He still could not speak of what he had seen.

He drank a cup of wine and his mouth felt cleaner. He was dressing when a message was brought that Alleen wanted to see him urgently. Thalia looked at him in fear and surprise.

‘What is it?’

‘How should I know?’

‘Show him in, then.’

Perhaps, he thought for a moment, he should see Alleen alone, without Thalia there.

‘Marith …’ Alleen was nervous. Excited, afraid. ‘Marith, I’ve someone here you need to see. Now.’

‘I … Bring him in, then.’ Should I tell Thalia to leave? he almost thought. He could hardly tell her to leave in front of Alleen and the guards prowling around.

What will I do, he thought, if it is coming now that she is the one betraying me? Or Osen? But I love her, and Osen is my best friend.

There was a young man waiting in the bedroom doorway. A servant, from the look of him … no, Marith looked closer, a soldier, unarmed and as frightened as Alleen was, but a soldier. Blood smell on him. Bronze and blood ground down onto him, marking him. The man was looking down at his feet, too afraid to look up.

‘Well?’

Gods, he needed a drink.

‘Speak,’ Alleen said.

We’ve been here before, and he’ll say … Not Thalia. Not Osen. Please. He’ll say it.

‘Lord Erith,’ the man said.

‘Valim Erith offered him gold,’ Alleen said, ‘to kill you. Gold and—’

‘Lord Erith gave me this.’ The man held up a dagger. Carefully, cautiously, between finger and thumb, hanging down like a live thing. Blue fire on the blade. A blue jewel in the hilt. Marith reached for it.

‘Careful!’ Alleen pulled his hand back away. ‘The blade is poisoned, he says.’

‘Poisoned.’ Marith took it, held it up to see the light move in the jewel. Pressed the very tip against his finger, drawing out a single bead of red blood. Heard voices gasp and wince.

‘Valim Erith gave it to you? To kill me? You swear this?’

‘Valim Erith gave it to me, My Lord King, I swear it.’

‘On your own life?’

‘On my own life, My Lord King.’

‘Why you?’ Thalia asked. ‘Who are you?’

A long, stuttering, gasping noise. The poor man. Wretched man, brought to this. He’s nobody, Thalia, Marith thought. Some poor man doing as Valim Erith ordered him.

‘Speak,’ Alleen said harshly.

‘My name is Kalth, My Lord King, I am an Islands man, My Lord King, I’ve been a soldier under Lord Erith since you were crowned king at Malth Elelane, I’ve fought in every one of your battles since you sailed to Ith, I’ve fought and survived them all.’ There was so much pride in his voice as he said that; his pride filled the room with warmth. ‘My brother died at Balkash. My lover died here in Arunmen, on the first day of the siege. Perhaps I … I said some things I didn’t mean, after he died, mourning him. He … It took him five days to die. So I was angry, and perhaps I said things … I’m sorry. But Lord Erith – I served him, my family have served the Eriths as soldiers and servants for a hundred years, he himself was a guest at my sister’s wedding, but I would not do it, My Lord King, not what he asked me to do.’

‘He came to me this morning,’ said Alleen. ‘He was supposed to do it last night. He hid, came to me instead.’ Alleen rubbed his eyes. ‘A hangover and four hours’ sleep. Curse Valim.’

Thalia said, ‘Can we trust him? This man?’

Alleen said, ‘Look at him. He has no reason to lie, I think.’

Thalia looked thoughtful. Marith rubbed at his own eyes, ‘Have Valim brought in, then. And fetch Osen here.’ Valim: yes, it made sense to him, he could see it; Valim whom he had known since he was a child, bright in his bright armour, his hard face, a proud young man in King Illyn’s hall. Not a friend. A friend of his father’s.

Valim Erith was brought in shaking his head, chained, guards all around him. His eyes bulged when he saw Kalth. But he did not speak.

‘You conspired to kill me.’ It was not a question. Managed to keep the question out of his voice. He remembered Valim Erith from when he was a child. A stern, cold man. He had always known that beneath the cold Valim Erith was weak.

‘Why?’ What do I expect, Marith thought, that he’ll say anything more than anyone else ever does? The same old same old things, the same words, the Altrersyr are vile and poison and hateful and should be wiped off the face of the world and I, I alone will manage it …

‘Where did you get the knife?’ Osen asked Valim.

Valim said in a whisper, ‘It’s not mine. I have never seen it before.’

‘Your man has told us everything, Valim,’ Thalia said, ‘stop lying.’

Marith held the knife up close to Valim’s face. ‘Was it you the prisoner was talking about? One of my generals, betraying me. You.’ Brought the knife so close to Valim’s face.

In the eyes. His own eyes itched and burned.

In the eyes. The blue jewel in the knife handle, blue as Thalia’s eyes. Is that some joke?

‘Are you killing my children?’ he shouted at Valim. ‘Are you making my children die in the womb? What are you giving her, to make it happen?’

In the eyes. So close to the eyes. His own face, reflected there. The knife, reflected there.

Thalia moaned in pain at that.

‘Are you conspiring against me? Are you?’

Kill him. Kill all of them.

I don’t want the child to live. Thalia doesn’t want the child to live. Thank him.

Valim said, ‘No. Marith. No. No. No. No. No. No. No.’ A flood of filth coming out of his mouth. Puking out his lies.

‘Stop it,’ Marith almost screamed at him. All the voices, so many, his own: no don’t do this please please no please. ‘No no no no no. Marith, no,’ Valim screamed.

Alleen said, ‘You cannot possibly have thought Arunmen would be able to defeat us.’

‘You were the one who brought the Arunmenese ringleader in to judgement,’ said Osen. ‘Gods, you snake.’

‘No,’ Valim whispered. ‘No.’ He stared at Marith, pleading. Stared at the knife. His body slumped. ‘I followed you, I loved you, I … You are my king, Marith … My son died for you … Marith!’ His voice rose again screaming. ‘It wasn’t me! You cannot believe this! You are my king! Always! Always!’ Scrabbled towards Marith, chains rattling stupidly. Dead body on a gibbet. ‘Always!’

Marith took up the knife again. Blue fire blue jewel. Fine bronze blade. A good weapon, well-balanced. It felt good in his hand. Could imagine it, very easily, sinking in. Now he knew it was poisoned, he could see a slight sheen to the killing edge. A slight scent, even, sweetish, dirty, reminding him of childhood sickness, over the cold smell of the bronze. His finger ached, where he had pricked himself with the knife. Wondered if this really could have harmed him.

‘Curse you! Curse you!’ A pause, a sudden look on Valim’s face like a cruel sly child: ‘I wish now that I had done these things.’ Then Valim said nothing more. Silent, hate in his eyes, as Marith killed him. The man Kalth screamed and shrieked, tried to break away, ended up on his belly wriggling, pleading, mass of snot and tears, clawing at the ground. Tal and Brychan killed him.

The wounds on Valim’s corpse blackened. Smoked and crumbled away. Black slugs, crawling over the knife wounds.

‘Bury it. Bury the knife, too.’ The first man to touch the corpse leapt back screaming. His fingers turned black. They had to wrap the body in raw hides, bloody and dripping, before they could carry it off. They threw Kalth’s body on top, shovelled the earth fast over it. Marked it with a pile of white stones: this place is cursed, keep away.

There was a sense of relief, afterwards. Marith felt a kind of lightness in him. Purged. Younger, brighter men than Valim around him. It must have been Valim. It must. Don’t speak more of it. Ignore it. His skin crawled running crawling with lice sand in his throat. Never speak of it.

‘He was never part of it, not like we are,’ Osen said, ‘he was thick with your father, gods know how long he has been plotting it.’

‘Filth,’ said Alleen. ‘You heard him at the end, confess it. “I had done these things”. I’ve been through the men who fought under him,’ Alleen said. ‘Had a good think and killed a couple of them.’

Thalia frowned, looked troubled, agreed it was for the best. ‘Are you sure, Marith? That it was Valim Erith?’

‘Yes.’

‘It just seems … I don’t know …’

Too neat, is I think what you may be saying, Thalia my wife. But blink it and drink it away. If it was more complicated than that, well. It’s done You did it, I think, or Osen, or someone all of you my dead children my unborn son. Valim Erith probably deserved it for something. Sand crunched in his mouth. So don’t think of it, don’t talk of it. Close your eyes, point at the map, give an order, march on.

The Army of Amrath left Arunmen behind it. Marched south through the wheat fields of Tarn Brathal, following the course of the sacred river Alph. The river ran cold through frosted landscapes. The earth was fresh and hard, the horses pushed on eagerly, the men marched singing, their voices crisp in the cold, puffing out their breath as they went. ‘Marith! Marith Altrersyr, Ansikanderakesis Amrakane! Death! Death! Death!’ Tereen, he besieged and destroyed, despite it having sworn allegiance to him as king. They had been lying. They would have betrayed him eventually, as Arunmen had. Risen up, cast off his rule, cursed him. Thus better to get it over with. The city fell and he went through the streets killing anything in his path, and he felt triumph and shame and relief. Filth. Rot. Corruption. They all loathe you, King Ruin. Want to see you dead. They deserve this, he thought. They would have come to this in the end.

Samarnath, he loosed his dragons on. A champion came out, dressed in black armour, a mage blade running with blue fire in his hand. ‘Fight me, Marith Altrersyr! Amrath! Fight me, I will destroy you! I have sworn it! Fight!’ They fought together, Marith and the challenger, wrestled and hacked at each other while all the living men and the dead looked on. He is invulnerable. He is death and ruin. He ached and stumbled and sweated and his mouth tasted of dust and blood and vomit, and he killed the fool in his black armour and sent him crashing down to the earth where his teeth stirred up the dust.

On again, still southwards, leaving the river Alph behind them. At its mouth was a great delta, a thousand miles of marshland, reeds and waterfowl, the people there lived on islands made of reeds, in huts raised up on poles above the water, in houseboats that rocked on the tide. They lived by hunting and fishing, prowled the wetlands on stilts looking like the wading birds they sought. Some of the marsh dwellers, it was said, had never set foot on firm hard ground. Stone to them was a marvel, more precious than bronze or iron: and what use was iron, indeed, when it rusted away in the constant damp? They worshipped the mud and the waterbirds, believed that the world was hatched from the egg of a giant black-winged crane. It might have been pleasant, Marith thought, to visit there, go hunting in the marshes, it was the season when the cranes would be gathering there to breed, from Theme, Cen Elora and Mar and all of Irlast. The sky would be dark with them; their wingbeats were said to make a sound like heavy rain. It was almost Sunreturn: back home on the White Isles it would be icy cold, dark even at midday, but here they were moving south, the air was warmer, the air had a different feel on the face, a new taste in the mouth.

The marshes were dying. Scouts brought the news in, proud and delighted to be the first to tell him. The waters of the Alph brought down rotting bodies, blood, disease, banefire, ash. The marshes choked on the poisoned waters, the reeds withered, the birds and the fish floated on the surface of the water bloated and green. Children sickened, their lives dribbling out of their mouths. Babies were stillborn. The old and the weak died of hunger. The strong died of grief.

So not much point going there, then, to hunt and boat. The cranes, the scouts said, were dying in such numbers that the channels of the river were choked with their bodies and their unhatched eggs.

The river is cursed. From being sacred, it is a river of death. It is punishing you, King Marith, by destroying itself. It worships you, you see? They marched instead for the Forest of Calchas, fragrant cedar wood, wild pears, walnut trees. Burned it. The dragons swept over it, belched fire, and the smell of the burning was sweet, as it always was. The flames, like the water, worshipping Marith the king.

Another feast, by the light of the forest burning. Osen had found a troop of acrobats who could jump and tumble higher than should be possible, they wore bells sewn over their costumes, mirrors on their costumes and on masks covering their faces and their hair. The air was warm, they could sit beneath the open sky. A great wall of flame and smoke to the west. The flames must be visible in Issykol, even on the shores of the Small Sea.

A cheer rose up in the distance. The whole camp was celebrating, the army enjoying itself. Singing and music. It would be lovely, Marith thought, to wander down there, join them, dance and drink with them as a man among them.

‘The Battle of Geremela!’ the lead acrobat shouted. The troop formed itself into two sides, took up long poles painted bronze. They vaulted, climbed the poles, flipped and darted over and under each other; clashed the poles together in the air; fell and leapt back up. It did look like a battle, a little, if one had never seen a battle. Osen and Alleen Durith cheered and clapped, their eyes very bright. ‘Do you remember?’ ‘Do you remember?’ ‘Do you remember?’ Gods. He could remember everything, every sword stroke, only had to close his eyes and he was back there. That moment, kicking his horse to charge down on the Ithish ranks, his men and his shadows following him. He had been the point of an arrow, the tip of a sarriss. That moment as he struck the Ithish ranks. So long ago now it seemed. The acrobats unfurled red scarves, whipped them behind them as they leapt, red banners snapped out from the tops of their poles. Bodies falling, leaping over each other. A final clash of all the poles together, the red silk burst over them, a girl threw a clay pot into the air, struck it with her pole to break it: white silk flowers showered down. ‘Hail King Marith! Hail King Marith!’ the troop shouted in unison.

Oh, that was lovely. Nothing like Geremela, but lovely. The acrobats bowed, a servant passed him a pouch of gold to throw to them.

‘Very clever. Very fine. Where did you find them?’

Osen was beaming, ‘Samarnath. Good, aren’t they? And the girl there, the one who threw the pot at the end … the things she can do …’

Kiana tossed her head at that, like she didn’t care. Which she didn’t. But who wants to be scorned even if they don’t return their suitor’s ardent love? Now you have a wife and a child and a true love and an acrobat mistress, Osen, Marith thought. A positive crowd of women. It was pleasing. The second most powerful man in Irlast shouldn’t just be moping about after Kiana Sabryya. And Alleen has his foul-mouthed singer; isn’t it a joy to see my friends so happy in love? Why else are we conquering all the world, wading through the blood of innocents, if not to meet beautiful young women with unusual talents?

A few days later he led an assault on a village fortress on the coast south of Calchas, a bandits’ nest, nothing of importance save that it sat on their march bristling with spears, could sit thus on their rear as a threat. Three days alone in command of fifty men, sleeping without tents or blankets under clear skies brilliant with stars, then a short sharp fight hand-to-hand at the end. The fortress was built over a spring of ice-cold water, tasting strongly of iron, Marith bathed in it, drank great gulps of it, it washed away any last memory of sand crunching in his mouth. When he got back to the army Thalia said his hair was curlier, too, from washing in it. In the bandits’ treasure store there was a necklace of rose-pink rubies, made for her, surely, and a string of green pearls that she gave away to Alleen’s foul-mouthed skylark-tongued girl. ‘Osen is happier, also,’ Thalia said, ‘than he has been. His acrobat is good for him.’ She laughed in bafflement at these men.

‘Why was Valim Erith such a fool?’ Marith asked. ‘Why? When he could have been part of this?’

Thalia opened her mouth to speak. Shook her head. ‘Because he was a fool,’ she said. ‘I don’t know.’

Thalia dreamed still of sweet water, wild places, birds: the feel of water, the smell of water, would be good for the child, she said. They made a fast ride to the shores of the Small Sea, Marith and Thalia, Osen and Alleen and Kiana and Ryn Mathen, camped there, watched the sun rise over the water. There was a great mystery in its waters, which in places were saltier than the Bitter Sea, in places sweet and fresh, safe to drink. One could swim, even, between areas of the two. It was the season in which the birds of the Small Sea raised their young, and the sky was filled with them, white feathers floated on the water’s edge.

‘We will take our daughter here.’ He stretched out full-length on the grass. He could no longer rest his head in Thalia’s lap but she ran her fingers through his hair. ‘We can teach her to swim in the water – much nicer than the freezing ponds I learnt in. The White Isles in winter, for snow and sledging and skating. Illyr in the summer, when the meadows are full of wild flowers for her to run through, as high as the top of her head. The shores of the Small Sea in the spring and the autumn, when it does nothing on the White Isles but rain and Ti and I would go mad stuck indoors for weeks.’

A great flock of white egrets came down on the water together, churning the water up, sending waves lapping against the sand on which they sat. So thickly packed that where they floated together they looked like an island. There were said to be dolphin in the water, and silver-coloured fish with long yellow curling hair like women. On the further shore the river Ekat ran down from the Mountains of the Heart, tasting of honey, the mountains were so high and so shrouded in ice that no one knew where in the mountains it rose. Some said the river Ekat was the tears of a dragon chained to a mountain. Some said it welled up from a great cavern glittering with diamonds, that led down to another world beneath. Some said there was a valley in the Mountains of the Heart where the people had wings like birds. Some said there was a city in the Mountains of the Heart where dragon princes lived.

Osen said, ‘When we get to Mar, the far south coast … we’ll have marched from the furthest north to the furthest south, when we get to Pen Amrean. The far end of the world. The Sea of Tears, and they say it goes on forever until you are no longer sailing on water but on … light, perhaps, or mist.’ He shrugged. ‘Until nothing. No one has ever sailed out, to come back. Unless they have tales of it in Mar or in Pen Amrean.’

‘I should like to see it,’ Thalia said. They had stood on the cliffs of the far north coast of Illyr, looking into the northern sea that has no end: ‘I should like to see it here at the south,’ Thalia said.

‘We can set up a marker there,’ said Osen. ‘They say the sea is warm there, the sea winds smell of spices there and the cliffs are silver-shining. An empire stretching from sea to sea. A tower, a monument, a mirror-image of the tower of Ethalden, silver and pearl. A tower greater and more beautiful than Ethalden, a palace, a house of glory for the king who had conquered from the furthest north to the furthest south, a monument to all his victories.’

Yes. On and on. On and on. Alleen shouted in agreement. Marith said, very quietly, ‘And then what we will do?’

‘Then what will we do?’

The sound of men’s feet, marching. The flash of their bronze spears held high. ‘Don’t abandon us, My Lord King!’ ‘Pension us off, will you?’ ‘Pay us, you bastard shit!’ Marith and Thalia, Marith and Osen, sitting by the fireside, children rolling happily at their feet, Marith and Osen have well-combed long beards, Thalia is stout and grey. Marith said, ‘When we have conquered the world. When there is nothing left to conquer. What will we do?’

Thalia sat up, looked at him. Osen said, laughing, ‘What do you want to do?’

‘Eralad, Issykol, Khotan, Mar, Allene, Maun, Medana, Sorlost …’ The awkwardness in his voice again, Osen was frowning, still trying to think it was fooling, Thalia made a little laugh noise in her throat to show she understood, and he brushed it away. ‘Chathe is our ally, Immish is our ally.’ Counting the places off on his fingers as he named them. ‘And then … we’ve conquered the world. There’s nothing left. So what will we do?’

‘That’s still a lot of places still to conquer, Marith,’ Ryn Mathen the King of Chathe’s cousin said.

‘Fewer places than we’ve conquered already, Ryn.’

Kiana said, ‘Pol Island. The Forest of Maun where there are a thousand miles of wilderness where a man has never been.’

‘Ae-Beyond-the-Waters!’ said Alleen Durith. ‘If Ae-Beyond-the-Waters is even a real place!’

‘That bit of rock off the coast of Allene!’ Osen shouted. ‘Those bits off rock off Maun’s coast! Places we’ve made up!’