Полная версия

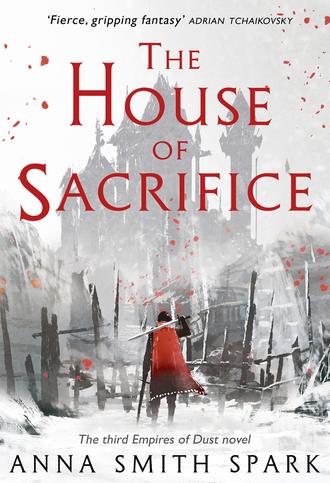

The House of Sacrifice

‘Turain, here we come!’

‘Woop woop!’

Tobias wandered off. Gods. Fucking gods. Tears in his eyes.

We were all that bloody innocent, once.

His own belongings were the basic definition of basic. A blanket. A cookpot. A couple of spare shirts and leggings. A spare pair of boots. The blanket was silk velvet, a stunning deep emerald green with a pattern of silver flowers, seed pearls crusted around the edge. The cookpot was copper and had an enamelled handle in the shape of a peacock, its tail fan spreading across the side of the pot. The shirts, leggings and boots must have been made for a prince. Several princes, as none of them matched. The Army of Amrath and the second army of camp followers following it marched around looking like peacocks themselves, resplendent, dazzling, a riot of colour, nothing fitting with anything else, nothing quite fitting the body it was draped on. There’d been excited chatter in the camp about Turain’s fashions and craft traditions for days now, everyone working out what they might want to get their hands on, putting in early orders with the soldiers, haggling over prices. Vultures. Though Tobias wouldn’t mind a new coat, if one happened to turn up.

Anyway. He bagged everything up, shouldered it. The whole camp was stirring, busying itself for the march.

‘Finally getting off, then,’ Naillil said cheerfully. A woman he knew, made her money doing the soldiers’ washing and sewing. She’d been with the army since Ith, way back. Longer than Tobias, in fact, technically. When Naillil started following the army, Tobias was still labouring under the impression he could do something else with his life.

Tobias nodded. ‘Finally.’ Had to say something more, really, somehow. Speak, Tobias! Don’t mumble at her and walk off.

Rovi said in his horrible dead voice, ‘Maybe King Marith’s hangover was really crippling him?’

Tobias shuddered. All this time and you’d think he’d have got used to Rovi’s voice and he never did and never would if he lived a thousand years and heard it every day.

Naillil said, ‘Rovi!’ Pretending shock.

‘Four days, we were all sitting around, after Lord Fiolt’s birthday. Ander almost had to sack itself.’ Dust puffing out of Rovi’s rotting toothless scar-tissue mouth. Smell like when you dredged the bottom of a pond after a sheep fell in. Rovi had been a goatherd. Thirty years man and boy tending his flocks in the highlands of Illyr, until the Army of Amrath turned up. Rovi had got stabbed in the chest and the gut and the neck during the battle of Ethalden. Rovi had ended up face down in the river Jaxertane, sunk in the mud and the filth for three days. Only somehow Rovi … hadn’t died. Kind of. Naillil had found him when she went to wash some shirts out. ‘Helpful for carrying my wash bags,’ she’d said once, and Tobias really wasn’t sure whether she meant something dirty by that or not. Really, really, really hoped not.

‘Here we go,’ said Rovi.

‘Here we go.’

Trumpets rang. Strange gathering sound of an army beginning to march. Tramp of feet and clatter of horses’ hooves. A rhythm to it, a music.

All day marching, through the mountains, beside the river that rushed down fast and wild and cold. The mountain slopes were covered with fruit trees, rich in birds and deer and wild goats. The sunlight came down through the leaves thick and golden, dappled the light, bathed their skin green. The men laughed and sang as they marched. A green tunnel, they were marching through, like being a child forcing your way through hedgerows, unable to see the sky, parting the leaves like parting the water of the sea. Then the path would rise, the trees would thin out, the sky would explode huge above them, deep joyous blue. The mountain peaks would appear then, and even in the warm damp growing heat, on the highest peaks of the mountains, there was snow. Marching on soft green grass, green bushes crusted with purple flowers, sweating in the sunlight, dazzled by the light and the blue of the sky. Then the path would dip again, the trees would close in around them, green soft damp cool heat. Felt different. Sounded different. The air tasted different in the mouth.

The fruit on the trees was poisonous, the camp followers had been warned. If you ate it, you’d swell up and sweat and die. When they stopped that night the trees had great knotted roots and twisting branches reaching almost to the ground. Hiding the world around them. Huge waxy pink and red flowers that attracted more insects than you’d believe possible. There were birds in the trees eating the insects, they had brilliant red feathers with black undersides to their wings. Tamas birds. They shrieked and called, sounded like they were speaking.

A whole village of camp followers setting down for the night. Endless babble of women warning their children against eating the poison fruit, smell of food cooking, smell of sweaty bodies, smell of human excrement. The sun was just setting. Warm and red like a healing wound.

Naillil was cooking stew. Asked Tobias if he’d like to join her and Rovi in having some.

‘Uh … Yeah.’ Paused. He could sit downwind of Rovi. And the stew smelled good. ‘Thank you.’

‘Want to help me wring out some shirts, afterwards?’

‘Uh … No.’ Paused. ‘Okay, then. Just this once.’

Tobias the bastard-hard sellsword! Hell yeah! Eased off his boots. Gods, his leg was bloody killing him this evening. Bad enough to make him forget about the pain in his arm and his ribs. When they’d eaten, Naillil called him over; he bent down over a pot of warm water, sank his hands in. Lifted the wet cloth up, water running back down into the wash-pot, the heavy feel of the wet cloth, solid and satisfying, the smell of the warm water in the warm air, the smell of the wet cloth. Twisted the shirt up to wring out the water, flicked it out with a good loud noise to get the creasing out. Water sprayed on his own clothes.

‘You’re good at this,’ Naillil said. She sounded surprised. Made a noncommittal secretly pleased nothing sound in his throat in answer, wrung out another shirt and enjoyed the feel of twisting the wet cloth. Naillil said, ‘Want to help me soap the next load, as well?’

Raeta the gestmet’s voice, weary: Not much else you can do with your life, I’m guessing, except kill? Tobias flicked the shirt out with a snap. Showered water over Naillil, who swore at him and laughed. Rovi sort of laughed.

From somewhere far off in the trees, a voice screamed.

Naillil looked up. Tobias looked up.

A howl in the air. A great gust of hot wind. More voices shouting. Screaming.

‘The dragon! The dragon!’ The sky lit up crimson. Fire blazing across the sky. ‘The dragon!’ a voice screamed. ‘The dragon!’

It came rushing over them, green and silver, huge as thinking, writhing and twisting and tearing at itself, swimming in the flames. Spewing out fire. Again. Again. Again. Again.

Soldiers came tramping towards them. Armed. Began killing them. Killing women. Killing children. The trail of lives that followed where the army led. Their women. Their children. Killing them.

Run.

Just run.

Tobias was gasping, wheezing, limping. His leg shrieking in pain and his arm shrieking and his heart and his ribs. Rovi next to him staggering, gasping, rot stink coming off him. Almost fell. Teeth gritted with pain. Up the slope of the mountain, towards … something. Nothing. Just run. Good rich black earth clinging sucking to his boots. Streams of people. Soldiers. Panic. Naillil shouted, ‘Look.’ A dark little cleft in the rocks, a cave, could hardly see it in the night and it looked like a wound in the hillside and it stank of blood like everything everywhere they had been. They scrambled up to it, crouched into it, sat in the dark, like sitting inside a wound. Stone walls close around them. Tobias gasping and sobbing in pain. Trying to gasp loud enough to drown out Rovi wheezing his horrible broken dead bad-water breath.

‘It will be over soon,’ said Naillil. ‘Few hours, at most.’

‘Yeah. Few hours. Like last time.’

‘She’ll stop it. Or Lord Fiolt will.’

Noises in the night. Wing beats. Voices shouting. Then horsemen passing very near them, riding hard. Trumpet calls. Then silence.

They emerged from the cave in the first light of morning. Voices crying. Footsteps on loose pebbles, jangle of bronze. A soldier’s voice shouting commands.

‘Line up there! We’re marching now.’

The slope of the mountain fell away very steeply beneath them, they must have scrambled up it climbing, Tobias could barely remember except that it had hurt. In the valley beneath them, a column of soldiers was marching off south. Staring straight ahead, everything neat and tidy, armour polished, red crests to their helmets very bright. They marched past in silence. Another column, spearmen with long sarriss, a raw red banner at the head of their files. It hung limp in the still air. Further up the slope, very near them, a party of horsemen. The smell of the horses was strong and pleasant.

There were great burn marks across the mountain. The fruit trees were burned away, rocks smashed up. The earth bare and black and dead. Figures picked their way across a wasteland of black ash.

A woman was standing a short distance from them. A dead baby in her arms. Her face and body were streaked with blood. Further down the slope a dead child lay sprawled, flies buzzing over it. A dead woman lay near it, her arms thrown out towards it. There were flies everywhere.

Oh Thalia, Tobias thought. Oh Thalia, girl.

‘She’s lost four pregnancies now,’ said Naillil. ‘Four pregnancies in four years.’ Naillil’s hands folded over her stomach. ‘You could almost pity her.’

She must have heard the sound Tobias was trying not to make. ‘I said almost,’ she said.

They began to walk slowly down the burned slope. Following the way the horsemen had gone. Tobias groaned in pain, rubbed at his arm. ‘Any chance any of our stuff survived, you reckon?’ One of the pointless things they said. Survivors coming together, the old hands who knew what to do to avoid the soldiers on the bad nights. Pedlars began to shout that they had cloths and blankets and cookpots for sale, cheap and best quality, lined up waiting for those who had lost everything overnight. The woman holding the dead baby began walking behind them. After perhaps an hour she grew calmer. Dropped the baby’s body. Walked on and walked on.

They stopped that night to make camp on the banks of a stream. Tobias made up the fire. Naillil began to prepare a pot of stew. Rovi sat and stank.

‘Why … why did he … do it?’ the woman whose baby had died asked them. Her name was Lenae. Couldn’t bring himself to ask about the baby’s name. Her hands moved and for a moment Tobias almost saw a baby cradled in them.

Why? Oh gods. Don’t ask that.

‘You haven’t been with the army long, then?’ said Naillil at last.

Lenae flushed red as the fire. Pulled her cloak around her tight. ‘I … My husband was a merchant in Samarnath. When the Ansikanderakesis Amrakane’s army came … One of the soldiers was kinder to me. Stopped another from killing me. He – so I – everyone there was dead, and he – I – then he must have been killed, at Arunmen.’ She looked away. ‘Why did he do it? Kill the children? Burn the camp?’

A branch moved in the cookfire, sending up sparks. The fire died down to embers. ‘Damn,’ said Naillil. Tobias got up and poked at the fire and moved bits of wood around and eventually it flared up bright and hot.

‘The queen lost her baby,’ said Naillil. ‘She was pregnant, and she lost the child … And last night the king … He …’

‘He was angry,’ said Tobias. Say it. That fucking poison bastard Marith. That sick, vile, diseased, degenerate fucking bastard. My fault my fault my fault my fault. ‘He ordered the … the dragon … ordered his soldiers to kill the children. All the children in the camp. He’s done it before. Twice.’

‘He’ll feel remorse, soon enough,’ said Naillil. ‘He probably does already. Gets drunk, orders it, cries when he’s told what he did. He’ll probably give a bag of gold to anyone whose child died in it. To make amends.’

‘Like he did before,’ said Rovi. ‘Twice.’

‘So you’re quids in, then, woman,’ said Tobias. He stared into the fire. ‘You can go home to the smoking ruins of Samarnath and live rich as an empress in the ashes there.’

Thought then: I let Marith kill a baby, once.

Once?

A few years ago.

Let Marith do it?

Encouraged him. Swapped a baby’s life for a sleep in a bed.

You look like what you are, boy, he’d told Marith before the boy did it.

Three days later, Lenae had five thalers in a bag around her neck she didn’t know what to do with. Buy a house somewhere and live long and peaceful. Bury them in a hole and piss on them and curse Marith Altrersyr. Drink herself senseless and pay someone to slit her throat.

The first, almost certainly. That’s what most of the women had done. Twice before.

That’s not fair, Tobias thought. Not fair. She’s got every right to make the best of her crapped-on ruined wound of a life.

Chapter Eleven

Turain! The land fell away sharply, the plain of the Isther river opening up, black earth and rich fields before the desert and the mountains rose again. Groves of white oleander. Peach trees. Dates. Golden plump wheat. Ah, gods, the smell was mouthwatering. The wind blew up from the south scented with ripe fruit, everyone drooled as they breathed it in. The river lay a wide silver ribbon, fat, smooth and sleepy, worn out from rushing through the mountain slopes. It is good here, Tobias thought. Really bloody nice. Turain smiled at them on the horizon. Not a very big city. Maybe even just a large town. Not much to look at, either, said someone who knew someone who knew some bloke. Grey and square and low, houses with narrow windows, gloomy inside and out. It had been sacked and pillaged and burned and smashed up and basically completely annihilated a surprisingly large number of times. So it had very, very, very, very strong walls. Not like they weren’t short on old stone.

‘Is it really worth the amount of pain it’s going to take to take it?’ Snigger. ‘Stupid question, yeah.’

The whole army sat and looked down on it. It sat and looked up at them back. The land around was completely empty. Abandoned villages, no people, not even a stray goat. Everyone and everything had fled inside the city. You got very, very, very, very strong walls, you’re hardly likely to do much else, are you?

‘They’d have been better off staying outside it, I’d have thought, myself,’ Tobias said conversationally to Lenae. ‘Those walls are like an insult to him.’

‘Never seen a city the Army of Amrath can’t break to tiny bits!’ a passing soldier shouted, riding past them leading a squad all in silver helmets, all mounted on beautiful white horses with gold saddle cloths. ‘Gravel, we’ll make of those walls. Use them as a grindstone for their defenders’ bones.’

‘Cowards, cowering there behind their walls! We’ll teach them the cost of cowardliness!’

Oh my eye, didn’t Lenae look impressed.

Tobias made a face after them. ‘Yup. As I was just saying. Only in a less naff way.’

The siege train got itself ready for action. The army went down into the plains and brought back a feast of ripe, slightly ash-stained fruit. Wonder the people of Turain hadn’t burned the fields themselves, in all honesty. But maybe they had too much pride for it. Or too much misplaced hope. Marith ordered the dragons out to soften up the city a bit. Everyone sat on the mountain slopes munching peaches and drinking date wine, to watch. Dazzling. Impressive. The red dragon had a great turn of speed on it, turned in the air on a penny, had this neat trick of rushing over, spinning around, rushing back so quick its fires almost seemed to meet. The green dragon was slower: it came down low, tore at the buildings with its claws as well as burning them with its breath. The people of Turain did pretty well against them, considering, loosed off various big missiles that did nothing, surprise surprise, but looked impressive and must have made everyone involved feel slightly better about things. Some mage bloke blasted light around: the spectators applauded politely when the green dragon shot up into the sky with one wing on fire, howling. Like watching a wrestling bout, you kind of wanted it to be a bit more of a matched fight. Support the underdog, like, for a while at the beginning. Not so interesting if the other side just caved from the off.

‘Date?’ Tobias asked Lenae. She shook her head, her mouth stuffed with peach. Juice running all sticky down her chin. Yeah. Nice to look at.

The mage bloke got the green dragon again, hurt it. Big groan rang over the mountainside. Gods, thought Tobias, gods, don’t tell me something’s actually going to go one up on him?

The green dragon and the red dragon met in the air. Quick conflab. Flew down over the city together. ‘Come on! Come on!’ the spectators all shouting. Underdog forgotten. Cheer of ‘Yesssss!’ as the mage sent up a blast of light that was abruptly snuffed out. Widespread applause. A curtain of fire came down over half the town.

The dragons seemed to decide that was game over. The place was indeed looking pretty well scorched and bashed up. They flew off overhead into the mountains, to oohs and aahs as they came low over. Nasty smell from the green one’s injured wing.

‘I’ll have a date, now, thanks,’ said Lenae. She got up. ‘That was amazing. When do you think we’ll go in?’

Weird, really, looking at the city, thinking this time tomorrow it was going to be rubble and human mince. The whole army lining up there, waving their sarriss around, marching back and forward pointlessly so King Marith can feel good about himself, knowing this time tomorrow they could be dead and there’s absolutely nothing any of them can do to make it any different.

Tobias sauntered off to use the nearest latrine trench. Most of the camp followers didn’t, filthy ignorant bastards, but. Pleasing, as always, that all the practical advice he’d given Marith about latrines had paid off. A lot of soldiers were squatting there with him, fresh from helping to chuck big rocks around and gasping with relief. All the fruit they’d been eating was, uh, having something of an effect.

‘Lovely display,’ said Tobias. Seemed apposite to say something, when you’re shoulder to shoulder with a bloke hearing the sound of his shit come out.

‘You what?’

Wait, no, not the— Oops, gods. Disgusting mind, you have, mate.

‘He means the siege, obviously,’ bloke on the other side of him said. And: thank you. Someone with a clean train of thought. Face burning, Tobias shuffled himself to sort of facing him.

‘Clews, man!’

Pause. ‘Uh, do I know you?’

Porridge boy. Yeah?

Oh, wait, no, he doesn’t know me. Can’t really say, ‘No, you don’t, but I wept over you, just recently, cause you reminded me of the life I fucked up.’

‘He’s a camp follower,’ the man who’d thought he was talking about the men lined up shitting said. ‘They know all our names, the camp followers do. Idolize us.’ Big, strong, solid-looking man, flashy hair, expensive cavalryman’s boots … some of the camp followers probably did know his name, yeah. He probably paid them extra if they screamed it.

‘Pathetic, they are, camp followers,’ Clews said. Sneer in his voice. Trying to make his voice sound loud and strong. ‘Men camp followers! Cowardly. Should be soldiering.’

Don’t rise to it, ignore it, you know what he’s doing, he’s a boy, it’s only bugging you because … ‘I was a soldier,’ Tobias said. ‘I spent years soldiering, I’ll have you know.’ Killed more men than you’ve had hot meals – for the love of all the gods, don’t say that, don’t. The cavalryman was grinning at them both, still crouching over the latrine trench. He’s got you right riled up, Tobias, this kid, and you know why, and just finish your crap and walk away.

‘Got scared, did you?’ Clews said.

Tobias stood up, knees creaking. ‘Got old and aching.’ Started to walk off.

‘That’s no excuse. My squad commander’s probably older than you.’

Stopped. Oh, gods, this boy. ‘Your squad commander got a knackered leg and a knackered arm and a broken rib that never properly healed?’ Your squad commander fought a demon and a mage and a bloody fucking death god?

Clews snorted. ‘Got men in my squad injured worse than that, still fighting on. A man in my squad with one arm. A man in my squad with half his face burned off. A—’

‘Yes, all right, okay, great, well done them.’ Gods, if I had a sword right now, a knife, a bit of sharpened stick …

‘When Turain falls, tomorrow,’ Clews said, ‘I’ll bring enough loot home to my family that they can get my sister married. If we get through the gates early, get the pick of the houses, I can bring home enough so my dad can stop having to work. And they paid a silver penny a head, they say, at Tereen. Couple of good strikes, that’d be enough we could buy the next field, hire a man to work it … And look at you, pleading your knackered leg.’

The cavalryman with the hair was sniggering now. He and Tobias exchanged looks. Rolled their eyes at each other. Well, yes … There’s that, yes, true enough. Gods, poor dumb kid.

‘It’s fucking awful, the actual fighting,’ Clews said. ‘But worth it.’ Sneer came back, faking it so hard it hurt you to watch. ‘If you’re brave enough. A silver penny a head, they said.’ He gestured vaguely towards the camp. ‘As we’re talking … you want to go for a drink?’

Suppose the kid could just be desperate to fuck someone on possibly his last night of living. Let’s try to be charitable here. Part of him wanted to take the kid off and listen, even, lend him a handkerchief, tell him it would be all right in the end.

Tobias said, ‘I’ve got things to do. Cowardly old-man camp-follower things.’

Decided to turn in early. Curled up in the tent. Went to sleep thinking of dragons dancing, peach juice dripping down Lenae’s chin.

You miss it, Tobias, man, he thought as he drifted up off to sleep. Bronze and blood and fire and killing. You lie to yourself, but you always will. You, washing clothes? Yeah, right.

Warm water smell, heavy feel of wet cloth, washing the fucking blood out.

Symbolic, yeah, don’t you think?

Chapter Twelve

Landra Relast, Marith’s enemy, sworn to defeat him and destroy him

Ethalden the Tower of Life and Death, the first Amrath’s capital, the City of the Ansikanderakesis Amrakane, the King of Ruin, the King of Death

When Landra had last been here, Ethalden had been a city of workmen, of raw stone slabs and stacked timbers, building rubble, scaffolding, workers’ huts, soldiers’ tents. The air had smelled of sawdust and stonedust, great clouds of it stirred up; the air had resounded with the shouts and songs of labourers and craftsmen. Marith’s fortress had risen up in the midst of this chaos, a glory of gold and mage glass and marble, heavy silk and shining fur and bright gems. Throne rooms, banqueting halls, pleasure gardens, crystal fountains pouring out perfumed water coloured red or blue or deep lush forest green. A central tower like a beam of sunlight was set at its very centre, so high it seemed to come down from the heavens to the earth. It was made of silver and pearl, hung with red banners; on balconies at its heights bells and silver trumpets rang out. Beside it stood two temples, one of gold dedicated to Queen Thalia, one of iron dedicated to Marith himself. In its shadow stood a tomb of onyx, holding the bones of the first Amrath.

Every master builder in Irlast had been summoned to Ethalden. Men who could work stone to create marvels, for whom stone could flow like water, who could pour out beauty onto the bare earth. Men with hands running with magic, with power over stone and metal to raise them up into dreams. Thirty days, Marith Altrersyr Ansikanderakesis Amrakane had given them to build him a fortress. If it was not completed as the sun rose on the thirty-first day, he would kill them. On the morning of the thirty-first day, the feast of Sunreturn, Landra had watched Marith ride into his fortress to be crowned King of Illyr and of all Irlast.