Полная версия

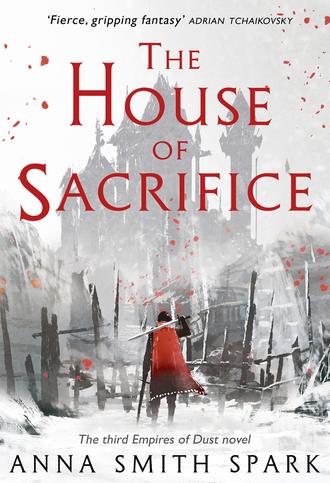

The House of Sacrifice

‘I can’t afford to pay them double. I can’t afford to pay them anything. You wouldn’t happen to have two months’ pay arrears in your jewellery box?’ Already, he thinks. Already. I thought they might stay there calling on me a little longer. As Thalia says, they suffered for me, they were victorious with me, they shed their blood for me. And yet this is so very easy. I have my kingdom, my palace, my queen, soon I will have a son. Sweet golden dreams of peace. In the courtyard only a very few of the soldiers are left now. Outraged shouts turn to muttered grumbles. Grumbles to knowing complaints. ‘Oh well,’ they say to one another, ‘oh well, we knew it would be coming. If he packs us off soon at least we’ll be home for the spring.’ ‘Got my wife a diamond necklace when we sacked Tyrenae. Was looking forward to giving it to her. Lost it to a whore one night when I was hammered. If the bastard pays us off, maybe I’ll buy her another one.’ ‘A farm, yeah? Never been outside Morr Town’s walls before we started marching. A farm might be nice.’ ‘Bastard. Throwing us over. But that’s kings, yeah? What else did we expect?’

That night the city of Ethalden is filled with whispers. Some of the soldiers drink to celebrate their return to homes and families. Some sit in lonely silence, weeping. Some shout their anger to the night sky and the sea. Marith walks the walls of his fortress, paces the corridors and halls. Seabirds scream in the darkness. Something that might be a hawk screams. It cannot be this easy. In the grey light of dawn he comes back into his chambers. In the bedchamber Thalia lies asleep, her face crumpled and strained.

‘The day when we were crowned King and Queen of Illyr, Thalia. Do you remember that?’ Little more than a month ago. He cannot remember it properly now. Too bright. Too unreal. Too wonderful. They stood in the great golden feasting hall, silver trumpets rang out like birdsong, every living soul in Illyr acclaimed them, the air itself seemed to blaze with gold. ‘The most perfect moment in any human lifetime.’ Grief overwhelms him. Self-pity and shame.

There are reports the next morning that there has been fighting in the city, groups of soldiers fighting each other, a mob of soldiers has been looting houses and shops. A small group of soldiers returns to the great courtyard to entreat him. Alis Nyman and Yanis Stansel go out to them, pay them off with silver pennies. They are grateful. Cheer their king. File away. Marith and Thalia, Osen and his wife Matrina, Kiana Sabryya and Alleen Durith go out for a day’s hunting. Blackthorn is budding in all the hedgerows. There are snowdrops in bloom by the roadside and faint traceries of frost on the north slopes. In the distance the great central spire of his fortress flashes out silver and pearl, hung with red banners that dance in the morning wind.

‘Are you growing a beard, Osen?’ Thalia asks.

Osen strokes the stubble on his chin, grins at Marith. ‘Possibly.’ He seems to be wearing a very ugly new brown coat as well, loose and badly fitting.

Thalia looks very hard at Marith’s chin.

They ride past a stream where the willow trees are furzed yellow with catkins. In the fields, they are ploughing the soil for the summer wheat. Thalia says, ‘I might well have two months’ pay arrears in my jewel box.’ The air smells so nearly of spring. When they get back to Ethalden there are petitioners waiting to ask the king’s judgement. A dispute needs to be settled concerning an Ithish lord’s inheritance rights. A messenger has come from Malth Tyrenae to report on the work rebuilding the city. The tax official on Third Isle has been dismissed for embezzlement, the king must approve his replacement. There is a letter from Malth Elelane reporting the financial situation on the White Isles, so that the king can be advised and take action. There is a letter from Malth Elelane reporting that a lord’s son on Seneth Isle has run off with another lord’s wife, the lord’s son’s mother is asking the king to do something.

That evening a group of soldiers gathers before the closed gates of the fortress, shout demands to see the king. But in many taverns the soldiers are drinking happily, raising a cup to their king who will soon send them home.

He goes to bed early. Thalia is tired out after hunting. He lies in bed listening to her breathing, and he cannot sleep. He goes up to the window, throws open the shutters, Thalia makes a moaning sound in her sleep. The night is clear and cold. He thinks of riding down to the sea, standing in the dark to listen to the waves beating on the shoreline. Tastes the salt damp on his skin. A gull screams high in the rooftops of his fortress. He thinks of dead bodies cast up on a beach.

At noon the next day he again summons the Army of Amrath before him. Stands again to address them on a dais hung with silver silk. The men stare up at him. They are wary. Frightened of themselves. Frightened of him They move and murmur like waves. A voice shouts, ‘Pay us!’ and is hushed. A voice shouts, ‘Don’t abandon us! Lord King! Please!’

How could he have thought it could simply end?

He cannot speak, at first. His mouth feels dry as desert sand. He stares down at them. They stare back at him.

His hand rests on the hilt of his sword. I don’t have to do this, he thinks. All I have to do is walk away.

He rubs hard at his eyes. His voice and his hands tremble as he speaks. ‘The army will not be disbanded. Not a single man of you. My companions, my most loyal ones, my friends. The Army of Amrath will be doubled in number! Every one of you shall be re-equipped in new armour with a new sword sharp enough to draw blood from the wind. There will be places in my army for your children, your lovers, your friends. All your arrears of pay will be compensated twice over. And in three weeks’ time the Army of Amrath will march out! You will be glutted with gold and with killing! My companions! My friends!’ He draws the sword Joy, holds it shining aloft, white light dancing along its blade. ‘We will see victory and triumph!’ His soldiers cheer with tears of happiness running down their faces. Alis Nymen cheers. Osen Fiolt cheers louder than any of them.

He thinks of Thalia cupping her hands over her belly. She just about shows now, when she wears a tight dress. The women of the court croon over her, fussing, ‘Oh, My Lady, how wonderful, how wonderful, oh, the greatest blessing a woman can have, My Lady, oh, joy to you, joy to you, My Lady Queen, My Lord King.’ Many of them had mothers or sisters or friends who died in childbirth. His own mother died in childbirth, a dead child rotting in her womb, it had to be cut up inside her, they say, extracted piece by rotting piece. The sounds a woman makes, in childbirth …’ The greatest joy of your life,’ the women say to Thalia, fussing. He knows it is.

He has some claim to the throne of Immier. His great-great-great-great-grandfather’s second wife was a princess of Immier; her father died without a male heir and the crown passed to someone else. Disgraceful. The throne should have gone to … whatever the girl’s name was. And the first Amrath conquered Immier a thousand years ago. Well, then. Immier is not a rich land. But there are many people there for his army to kill.

‘Death!’ the men chant, loud as trumpets. How much they love him! ‘Glory! Glory! King Marith!’

His uncle’s voice, mocking him: ‘You were such a happy child, Marith. But one might have guessed, even then, that this would be where you’d come to in the end.’ Where any man would come to, once they started on this.

He thinks: Immier, Cen Andae, Cen Elora, the Forest of Maun in the furthest south of Irlast … it doesn’t matter where we go. We will march, we will fight, we will kill, we will march on. We dream of glory, and we must have more glory, and more, and more. Men grow restless, look wistfully on swords growing blunted, dream of times past when they were as gods. Looted coin is soon spent.

Thalia miscarries that same evening. The first of them: she has lost two more children since, on the march; they are marching still and now she is pregnant again. He still owes his men two months’ arrears of pay. But, now, behold, half the world is conquered.

The dragons were black dots in the white snow sky. Marith rode back to Arunmen through the snow falling heavier. Thick soft white flakes like feathers. Falling until he could barely see his hand in front of his face. He rode along unconcerned. A king in his kingdom. Silent in the snow. A wolf slunk past almost in front of his horse’s hooves. Looked at him. Sadder eyes than the dragons. What might have been a scrap of human flesh in its mouth. The horse snorted, rolled its eyes. The wolf was injured, like the green and silver dragon, a long wound running down its flank. Maggots crawled there, even in the winter snowfall. It was heavy and fat from glutting itself on his dead.

‘Denakt,’ he shouted at it, as though it was another dragon. Go. Leave. It stared at him. Padded off, disappeared into the snow. He rode on, in a while came across the body it had been feeding on, a man, torn apart lying there. Someone who didn’t want to be a soldier, he’d guess. Tried to escape his men. The face was untouched. Mouth open. Eyes open. The snow slowly covering it.

Chapter Seven

Envoys came to Arunmen from Chathe and Immish and every city of his empire, brought him gifts from every corner of the world. Treasures and jewels, objects of great beauty and wealth. White horses. Silver cloth as light as sea foam. A thousand ingots each of iron and copper and lead and tin. The emissaries from Chathe came to kneel before him, swear their loyalty. He smiled at them, raised them up, promised them his faith back in return as long as they remained loyal to him. Ryn Mathen nodded, eyes bright with happiness. On a whim, Marith ordered the emissaries to be given a hundred chests of gold and silver, to bring back to King Heldan as an honour gift. The lords of Marith’s empire knelt and crowned him with wreaths of flowers. He held races and dances and feasts. The soldiers paraded for him, dressed in their finery, polished bronze, red plumes nodding on their helmets, red cloaks, gleaming, marching and wheeling in the snow. The music of the bronze: they danced the sword dance, clashed their spears, shouted for joy. So many of them, uncountable, like the trees in a forest. They roared out his name with triumph, he who had given them mastery of the world, made them lords of life and death. Their love burned off them, warm and joyous; Marith gasped as he watched them, his face radiant, breathless, still, after everything, half unbelieving, all this, all this, for him. The emissaries departed, leaving more allied troops in his army’s ranks. The Army of Amrath prepared to march out. The forges rang with the clash of hammers, the glowing fire of liquid metal, burning day and night. More swords! More spears! More helms! More armour! Grain carts rumbled in beneath the ruins of the gateways. Provisions for a long hard march. A new levy of troops marched in from Illyr, young men who had not yet seen the glory of his conquests, staring wide-eyed and hungry at the ruins of the city, the tents piled with plunder, the campfires of his army numberless as the stars. They marched in between towers of white newly slain bones, white skulls grinning, the shriek of carrion birds. He saw in their eyes the wonder, the longing to be part of this. They saw him, and he felt their love rise like mountains. A marvel, a gift unparalleled, that they could look upon him, fight for him, swear to him their swords and their spears and the strength in their body and all the length of their lives, to kill and to die at his will.

Onwards. Ever onwards. New lands to conquer. The road goes on and on. Issykol. Khotan, with its sunless forests. The lawless peoples of the Mountains of Pain. Turain, with its wheat fields and its silver river. Mar. Maun. Allene.

The Sekemleth Empire of the Golden City of Sorlost.

Gods, he sees it, so clear in his mind. Yellow dust, yellow sand, yellow light. Magnolia trees and lilac trees and jasmine, all in flower; women in silk dresses, bells tinkling at their wrists and ankles; in the warm dusk the poets sing of fading beauty and the women dance with grief on their crimson lips. The golden dome of the Summer Palace. A boy falling backwards through a window, lit by a thousand glittering shards of mage glass. In Sorlost I saw her face for the first time, radiant, and when I saw her I knew. My hands wallowing for the first time in innocent blood there. In Sorlost I killed a baby, I looked down and I ran my sword through it because I could. Sickness filled him. Fear. He thought: don’t think of it. There are so many places to conquer before I have to go back there.

At night he lay with Thalia in the bedroom with the green glass windows, beneath the mage-glass stars. Thalia naked and glowing, bathed in light. He rested his head on her stomach, imagined he could hear the child’s heart beating. In the dark inside her body it swam and dreamed. Absurd and impossible.

‘I can feel it move,’ she said. ‘Fluttering inside me. Like a bird. Like a butterfly landing on my hand.’ My child! he thought. My child!

He said, ‘This time it will live.’

The shadow flickered across his mind. He who had killed his own family. The fear, that it would live.

Alleen Durith held a celebration dinner the last evening before they marched. A private thing, Marith, Thalia, Osen, Kiana Sabryya, Dansa Arual, Ryn Mathen. Alleen’s chambers were decked with silk flowers. Marith was noisy, happy, laughing, the lights were very bright, the air smelled fresh and good. Thalia glittered in his vision, silver and bronze, silk and water, summer rain.

‘Do you remember the morning it rained,’ he said to her, ‘in the desert, and the flowers came out pink, and the stream came rushing down?’

Thalia said in surprise, ‘No. I … I don’t remember.’

‘I remember it so clearly. The way the desert came alive. How can you not—?’ Or …? ‘No, that was before, wasn’t it? You didn’t see that. We saw the stream with the willows, and that first stream, where we threw pebbles, and I told you who I was. It didn’t rain in the desert when you were there with me. But you’d never seen running water, until I showed you the stream, and you bathed your hands and feet in it …’

‘No,’ Thalia said, confused. ‘No. I hadn’t. I—’ She smiled then: ‘It was beautiful, Marith, when we saw the stream. I remember that. I’ll never forget that. Like seeing the hawk – was that on the same day?’

The hawk? What about the hawk? ‘We’ll go back there soon,’ he almost said.

‘Drink up, everyone,’ Osen shouted. Bustling around, refilling cups. ‘Tastes like goat’s piss, but we can all manage another cup.’ A good and clever man, Osen Fiolt. A good friend.

‘Goat’s piss? Goat’s piss?’ Alleen raised his cup. ‘I looted this stuff personally, Osen, you barbarian. Horse’s piss, at least.’

Kiana threw a flower at Osen. ‘War horse’s piss. I helped him choose it.’

‘Did that woman ever send a bottle of her good wine?’ asked Thalia.

‘I don’t know.’ Looked at Osen and Alleen. ‘Did she?’

‘I have no idea what you’re talking about, Marith.’ Osen chucked Kiana’s flower at him and shoved over a plate of sweets.

‘I found a girl in Arunmen who can sing like a skylark,’ said Alleen, ‘if anyone’s interested in hearing her sing?’

‘“Sing like a skylark”?’ said Kiana. ‘Cousin, really.’

Thalia yawned. ‘I will go to bed, I think, Marith. I’m tired.’ She was very tired, suddenly, the last few days, slept and ate a lot. But she looked well, her face was shining, it would be well, this time, surely, the doctors said that it was good that she was tired, because it showed that the baby was strong. It will live, it must live … he felt sickened, thinking of it, gulped down his drink, found himself looking away from her. My child. My child. I who killed my mother and my father and all of them, what will my child be if it lives?

‘Stay a bit longer, Marith,’ said Osen. ‘This girl of Alleen’s can sing The Deed of the New King and The Revenge of the King Against Illyr like a skylark. The proper songs and the dirty versions.’

‘Her dirty version of The Revenge is … dirty,’ said Alleen. ‘You have no idea.’

Osen began to sing, ‘His big big sword thrusts hard and wide.’

‘I will certainly go to bed,’ said Thalia.

‘I fear you may be wise, Thalia my queen,’ said Osen. ‘Whole cities call him to thrust inside.’

‘Come to bed soon, Marith,’ Thalia said as she left them. Her hand brushed his arm as she walked away. ‘Won’t you?’ Pregnancy seemed to leave her insatiable. It made her flatulent, also. Slept and ate and farted and wanted to fuck. All the good things.

‘And she sings it completely straight-faced, too,’ said Alleen. ‘A marvel.’

Umm …? Oh. Yes. ‘Do I really want to hear a woman singing obscene songs about my triumphs?’

‘Of course you do,’ said Alleen.

‘Do I really want to find myself humming it the next time I …?’

‘Of course you do,’ said Alleen. ‘And it makes me happy just thinking of it. Why else are we conquering all the world, wading through the blood of innocents, if not for people to make you the subject of obscene songs?’

A loud click of metal as Kiana put her cup down. Alleen went white.

‘It’s no worse reason than some.’ Try to laugh. Try to smile. Try to laugh. His face felt so hot. That feeling, that he had had when they were cheering him, singing his name outside the ruined wine shop, joy, bliss, wonder, but I felt shame, he thought, then, hearing them, and I feel shame thinking about it now, and thinking about a girl singing songs about me … My eternal fame, my glory, the songs of my triumphs … His face felt hot and red. Like it’s humiliating, that they praise me. Like they and I are both wrong, should be ashamed.

My head hurts, he thought. I need to go to bed as well. I should have gone with Thalia just now.

‘I won’t have the girl summoned,’ said Alleen. ‘I’m sorry, I don’t know where that came from. Stay and have another drink, don’t leave looking like that. Please.’

‘One drink.’ It is no worse reason. He’s my friend, I …

Osen and Alleen were singing something. Kiana was crying with laughter at it. He was singing it too. He was stumbling back to his chambers. It suddenly seemed to have got very late. The girl had sung like a skylark. Even Kiana had admitted as much. Kiana had smiled at Osen: it would be so good if she was to return Osen’s feelings. Make him happy to see it. Poor old Matrina, Osen’s wife. He had always rather liked Matrina. But Osen liked Kiana. Kiana didn’t seem to like Osen. I wonder if Matrina would like Kiana? he thought.

‘My Lord King!’ his guardsman Tal shouted.

He was blind. Felt like he was being buried in sand. Thrashed about, gods, it was sticky, coating him. Hands flailing. Filth, coming all over him. His skin burning. Itching. Filth coming up through his skin. He had seen a dog once all covered crawling with ticks and sores and lice, its skin its fur moving. His skin was crawling. Erupting. Rotting. He retched. Vomit filling his mouth, vomit and sand, and he tried to swallow it, he couldn’t swallow it, it burned at his lungs, felt it in his nostrils, his eyes bulging, his head going to burst, choking, trying to claw at his nose and mouth. I’m drowning. Gasping to breathe and there was nothing. His arms and legs trembled. Cold sweat pouring off him. Tore at himself he itched he was crawling his skin was crawling his skin erupting his throat erupting choked blocked crumbling he was choking, drowning, his skin, his throat blocked with filth.

The sound of metal. Voices cheered. A trumpet rang.

Swords, he thought. Fighting. A vast battle, men fighting in their thousands in the hallway around him. A hundred thousand shining sword blades.

Gasped, vomited up sand. On his knees, sand pouring out of his mouth. Great gouts of it, like the dragons pouring out fire. Breathing again. Gasping down air. His throat and lungs raw. Sand and vomit dripping from his nose and mouth.

A shadow stood over him. A thing like a man. Dark, like a shadow, featureless, an outline of a man, like a man’s shadow in the half-light, and then it moved, poured itself back towards him, a thing like a man but all formed of black sand, crumbling away as it choked itself over him.

He had seen such things in the ruins of his victories. The destruction of the body in a wave of dragon fire. Flesh and bone turned into black ash.

Its hands reached again for him. Pouring towards his throat.

Buried his hands in it. It came apart around him. Flowed over him. The faceless head pressed towards him. Its arms embraced him. Pouring itself into him.

Threw his hands up over his face. Covered his mouth with his hands, bent down pressing his face into the stone floor. Hugging him to itself, kissing and devouring him. In his eyes. His ears. His mouth.

Vengeance. Hiss of sand in the wind. Tried to squeeze his eyes closed, tried not to breathe. It clambered itself swarmed itself over him into him. Vengeance.

A hand on his shoulder. He sat up.

‘Easy there, My Lord King. Careful.’ Tal helped him up carefully. Propped him against the wall. Marith bent forward and coughed up a last trickle of vomit.

‘Heavy night, was it, My Lord King?’

Blinked, stared down the corridor. ‘There was … was …’

Tal helped him up the stairs towards his own chambers; he had hardly gone a few steps when Thalia was rushing down to him, her guard Brychan there beside her with his sword out. Pain in her face when she saw him.

‘Marith!’

‘It’s nothing. Nothing.’

Her foot slipped on a step, he cried out but Brychan caught her arm, then she was beside him.

‘It was nothing,’ said Tal.

Black sand gushed off him. When he looked there was no sand on the floor. Sand crunched in his mouth. He spat. Thalia looked shocked at his spit on the floor. Gleaming. Someone else spat, he thought, I saw a man spit green phlegm at my feet.

‘Have some water, Marith.’ A cup in his hands, heavy goldwork that heaved beneath his fingers. Itching, crawling, moving. He drank and gulped it down. Tasted so sweet. A grating feeling in his throat as he swallowed. Hair and gristle. Dirt stuck in his throat. His mouth was running with lice. He gagged, his hand over his mouth, don’t be sick here in front of her, my wife, do I want my wife to see that? The shame … once I didn’t want her to see my face, because she’d see it there, vomit and death, I’m human fucking vomit, filth like I’m choking down.

Thalia brought all the lamps in the room to burning. They were in their bedchamber. He couldn’t remember walking there. The green glass windows were black and hollow, black voids; the lamplight made the mage-glass stars in the ceiling faint and dull. The silver hangings on the bed moved, trembled: the warm air from the lamps, someone had told him, one of the maidservants. Her sweat in the lamplight, running down inside the neck of her dress … The leaves and flowers on the walls looked too real, like wax flowers. Obscenities like a swollen body. Draw his sword, hack them down to bits. The scabs on his left hand were diseased. The scar tissue alive with parasites. The scars on Thalia’s left arm were alive with parasites. The scars on her arm were crusted cracking infested with maggots. His throat was dry with dust.

‘You almost slipped,’ he said. ‘On the stairs.’

‘Brychan caught me.’ She put her hands over her belly. Her nightgown was very sheer, very fine silk, he could see the swell of the child growing there. No other child had grown this big in her womb. Blood smear things on her thighs. Clots of stinking blood. Pregnancy had made her breasts huge. Sweat on her, between her breasts, staining the sheer cloth. He felt sick. For a moment it seemed to him that her belly was swollen not with a child but with ash.

‘He’s safe,’ she said. ‘I was worried about you.’