Полная версия

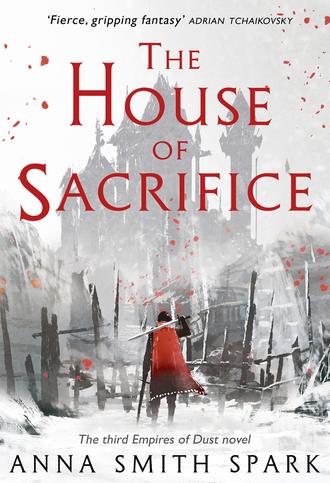

The House of Sacrifice

She looked out over the frozen landscape. ‘I suppose we should. I could stand here forever.’ She sighed, laughed, put her hands on his wet snow-crusted cloak. ‘You’re getting cold?’

‘The horses,’ he said with dignity, ‘are getting cold.’

They rode back through the ruins of Arunmen. Thalia wanted to see. Always, she wanted to see.

‘I need to remember,’ she said. ‘I am not ashamed of it: they fought us, they lost. Such is the way of things. Some draw the red lot, some draw the black or the white. But … I should remember. See it for myself.’

The city was a desolation, black rubble, the great obsidian walls tumbled down. Pools of blood, frozen, black and hard like the stone, the whole city glazed in blood. Fires still burning, dragon fire so hot the very stones were cracked open, holes in the earth where the fury of the fighting had devoured itself. Bodies in the rubble, under ice and ash and snowfall, dead faces masked in snow, rimed in blood. Burned. Dismembered. Hacked up and swallowed and spat out. Marith steered the horses carefully away from the ruined temple. Fragments of yellow paint. Around the palace, a new city of the Army of Amrath was forming: soldiers’ tents, cookfires, canteens, workshops. A smithy was working: Marith heard again the ring of the hammer, breathed in the hot metal scent. A hiss that was molten bronze being poured. A boy in a scarlet jacket embroidered with seed pearls, gold at his neck and waist and ankles, his face running with hatha sores, touting offering himself for one iron piece. A pedlar shouting his wares: ‘Tea and soap! Salt and honey! Spices! Herbs! Lucky charms!’ Two women washing clothes in a silver bowl that must once have graced a lord’s table. Plump glossy children in fur and satin, playing snowballs in the ruins of a nobleman’s great house. One of them hit another straight on, got snow all over her coat, and Marith laughed.

Some enterprising person had got a tavern back open. The front wall and the roof had been completely demolished; they’d made the best of it by setting up a fire for mulled wine and laying out some brightly coloured rugs; rigged up the remains of a soldier’s campaign tent to keep off the snow. It all looked very charming. Marith nodded at Thalia, they dismounted and tethered the horses, wandered up.

Everyone recognized them, of course, so they walked through a sea of prostrate bodies, more and more people running to kneel, to be in his presence, to see him through half-closed eyes. Voices ran like seawater: ‘The king! The king! Amrath Reborn! Ansikanderakesis Amrakane! The king! The king!’ Someone starting a song of praise for him.

Bliss.

Blush rising in his face from sheer delight at it. He laughed with joy.

They sat down on the bright pretty rugs, the woman running the place rushed over with cups of hot spiced wine, a dish of keleth seeds, a dish of cakes. The cups were enamelled silver, yellow garlands around a scene of fighting birds. Very finely done, actually: he’d guess not from the tavern but looted from somewhere in the east and lugged halfway across Irlast. The wine was delicious, thick and golden. Also looted. The cakes were stale and dry as sand.

The tavern woman prostrated herself flat on her face in the snow. ‘I am honoured beyond all honour. My Lord King, My Lady Queen, I kneel at your feet, I am your slave. Take the cups, the plates, everything here in this tavern, our gifts, our token of our love for you.’

Beyond bliss. Ah, such a good thing, to be loved like this. He smiled down at the tavern woman, told her to get up, kissed her hand. Drained his cup, waved over a passing soldier: ‘Take this cup back to the palace. Have Lord Durith summoned, tell him to send a dozen gold cups to this woman in place of this one she has kindly given me.’ The woman went pink with astonishment. Tears in her eyes. Thalia laughed with delight.

‘My Lord King. My Lord King. Thank you. Thank you.’

‘I’ll take a bottle of this wine, too, then, if I may?’ Marith said, smiling at the tavern woman. ‘It’s better than the wine they served my court last night.’

More laughter. The woman said, a look of great daring in her face, ‘I need the wine, My Lord King, for my customers, who must have higher standards in drink than your court.’

Ha! ‘They do. They do. Anyone in Irlast has higher standards than my court.’

He settled himself further back on the rugs, stretching himself leaning against Thalia. Ate another stale cake. The tavern woman poured him another drink in a new cup. She was wearing a ring on every finger; they clinked musically against the glass of the bottle. She had silver earrings that jingled, her dress was green velvet. She was positively fat.

Raised a toast to her. ‘I’ll buy a bottle for a hundred thalers. Make you a lady of my court.’

‘But I’ll make far more than a hundred thalers, My Lord King, telling my customers they’re drinking wine I refused to sell to the Ansikanderakesis Amrakane the joy of the world the King of All Irlast.’

Gods, she was good. He got up and bowed to her. ‘Like the wine, you’re too fine for my court. I’ll give you a hundred thalers anyway.’

‘And I’ll give you another bottle of this wine for free, My Lord King.’ Her earrings rattled, she looked at Thalia sitting in her thick fur cloak. ‘And, if I may, if I may be so bold, My Lady Queen …’

Oh ho. Marith tensed, Thalia tensed, relaxed both together, smiling at each other, squeezed hands. The whole army knows. The tavern woman went into the back of her shop, Marith ate a third stale cake in the time she was gone.

Thalia whispered, ‘A horrible itchy baby’s dress? A blanket? A pair of absurdly tiny booties?’

‘A blanket. Hand-knitted. Shush. You’re being cruel.’

‘And you’re getting cake crumbs on my cloak. How can you eat them, anyway? They must have been baked last week.’

‘Amrath lived rough with his army …’ Wiped crumbs from the white fur, leaving a yellowy smudge. Whoops. Maybe she wouldn’t notice. He tried surreptitiously to pick at the mess. ‘Anyway, shush, she’s coming back.’

‘A blanket,’ Thalia whispered. ‘Dark red. With a sword pattern on it.’

He almost choked crumbs over her. ‘Shush!’

The woman returned smiling. Didn’t look like she was carrying a blanket … She held out a branch of white flowers to Thalia. ‘The tree behind the tavern here flowered this morning, My Lady Queen. All out of season – the dragon fire, we thought maybe, My Lady Queen, the heat. But here. Perhaps it flowered for you.’

‘Thank you.’ Thalia bent to sniff the flowers’ sweet perfume. ‘Thank you very much.’ They finished the wine, Thalia made a face of mock terror at Marith that they’d be offered another plate of cakes. When they had ridden away out of earshot they both burst out laughing. The sun rises, the sun sets, and not everyone in the world thinks only of tiny booties and baby blankets.

‘But the flowers are very beautiful,’ said Thalia. ‘How strange, that the tree flowered in the snow. Do you think it was really the dragon fire?’

‘It’s wintersweet blossom. It’s meant to be in flower now.’ He was beginning to feel rather sleepy after all the wine and cakes. ‘That’s what it does. Hence the name.’

Thalia looked down at the branch, which she had woven into her horse’s reins. ‘It’s still beautiful. We should plant it in the gardens at Ethalden.’ Looking down at the flowers, she noticed where he’d got crumbs rubbed into her cloak. ‘What’s this? My new cloak … Oh, Marith. Cake crumbs.’

He looked at her belly. ‘Get used to it. I had to have cake crumbs cut out of my hair once.’

Chapter Six

‘I had to have cake crumbs cut out of my hair, once.’

Ti’s hair. His mother – his stepmother, the bitch who killed his mother, remember, remember that – his stepmother had had to cut cake crumbs out of Ti’s hair, once. He had killed Ti and he had killed his mother. Hung their bodies from the walls of Malth Elelane. He remembered the way his mother’s hair had blown in the wind.

Three miscarriages. But after three months, four months, the pregnancy is more established, the baby is more likely to be born and live.

He felt sick. The stupid stale cakes.

The next day Marith rode out alone. The land was very empty, the burned fields blanketed in snow. A few surviving villages clinging on in the ruins, ragged-faced farmers tending their cattle. His soldiers were out, rounding up the cattle, pillaging the villages for food and men for the army to consume. A ravening beast, an army. Never ceased its hunger. Indeed, its hunger grew and grew.

Rode past a line of men and women in tattered clothing too thin for the weather, sick faces staring. Rounded up to march in his army. Men and women and children and old men and cripples and the maimed and the half-dead. It didn’t matter who they were. Whether they were strong or weak. If they had no other use, they would deflect an arrow or a sword. If they had no other use, they would die. The soldiers with them prostrated themselves in the snow when they saw him. The new conscripts stared, then did the same. Whispers. His name cried in blessing. The joy in their eyes, radiating off them, the fulfilment of their lives, to see him.

King Marith! King Marith! Ansikanderakesis Amrakane! I can die now, for my heart and my eyes have beheld him.

Marith pulled up his horse before them. ‘We will fight,’ he called to them. ‘You will march in my army, and you will fight, and you will be victorious, and you will conquer the world! This gift, I give you. All of you, you will do this. Conquer the world!’

‘Death!’ the soldiers cried back to him. Shining in ecstasy. ‘Death! Death! Death!’

He stopped around midday in a bare high place without any signs of human life. No – there, to the west where the land dropped down into a valley, a single plume of hearth smoke rose. A little village sheltering there, perhaps.

No matter. He dismounted, stood against the white sky. Raised his arms. Called out.

‘Athelamyn Tiamenekyr. Ansikanderakesis teimre temeset kekilienet.’

Come, dragons. Your king summons you.

A long silence. And then the slow beating of vast wings.

Weak things, dragons. Far weaker than he had first thought. Ynthe the magelord saw them as gods and wonders. Osen and Alleen thought of them as toys: ‘Ride it, Marith’, ‘Just use it to kill them all, Marith’, ‘Make it sit up and beg and roll over at your feet’. He himself had thought that the dragons were like him, once. The only things in all the world that might understand him. Things of love and desire and hunger and grief and need. He had been a fool, to think that.

He thought: do dragons rear their children? Care for them? Feel love?

He thought: no.

The dragons came down in the snow before him. One black and red. One green and silver. Huge as dreams. He had summoned them out of the desert along the coast of the Sea of Grief, called into the dark and they had come together side by side, their wings almost touching. They could be mother and child, lovers, siblings; what they thought towards each other he did not know and could not know. What they did, when he did not need them, he did not know. Dark eyes looked at him. Like looking down into the depths of the sea. Never look into a dragon’s eyes. Look into a dragon’s eyes and you are lost. Eyes black with sorrow. Such hatred there, staring vast ancient unblinking down at him.

He thought: I call them and they come to me.

The dragons turned their heads away from him. Lowered their eyes. The red dragon spoke in a hiss of fire. Dry rasp of pain. Its breath stank of hot metal. Dead flesh rotting in its yellowed teeth.

‘Kel temen ysare genherhr kel Ansikanderakil?’

What is it that you want, my king?

I don’t know, he thought. What is it that I want? I want to die, he almost said. The red dragon almost spoke it. The words there in the stink of its breath. I want to die: kill me, he almost said.

Or kill the soldiers. My soldiers. Come down in fire, burn my army to dust. We spread out across the world in blood and fire, we have destroyed half the world but the world is endless, the road goes on and always there is another conquest waiting on the horizon. All I need to do now is speak one word to make it stop.

Dragons are not gods, he thought then. Not wonders. There was nothing in the world that they could give him. Huge things, huge as dreams; he stood between them tiny and vulnerable. He could crush them.

‘Kel temen ysare genherhr kel Ansikanderakil?’ the red dragon asked again.

‘Ekliket ysarken temeset emnek tythet. Ekliket ysarken temeset amrakyr tythet. Ekliket ysarken temeset kykgethet,’ Marith said in reply.

What is it that you want, my king?

I want you to bring death. I want you to bring fire. I want you to kill.

Always the same words. The same commands given. Kill! Kill! Kill! On and on forever. On and on until the world ends. So close to asking. But I don’t ask. Why do we waste our breath saying it?

If my army was destroyed, he thought, I would cease to be king. What would I be, if I were not a king?

‘You are tools,’ Marith shouted at the dragons. ‘Nothing more. Things I send out to kill.’

The dragons nodded their heads in obedience. The green dragon might smile, even. Scars on it deep in its body, wounded, its body moved with the awkwardness of something in pain. The red dragon thrashed its tail. Hating him. Tired. Old. Just wanting to sleep.

The green dragon said, as it always did, ‘Amrakane neke yenkanen ka sekeken.’ Amrath also did not know why. ‘Serelamyrnen teime immikyr. Ayn kel genher kel serelanei temen?’ We are your tools. And what are you?

They leapt into the air together. Red and black, green and silver, so huge he was left blinded. The snow where they had crouched was melted. He watched them spiralling up and outwards. Off to the south, towards the Forest of Calchas, the Sea of Tears, the Forest of Khotan. Tiny jets of flame on the horizon. Or perhaps he was imagining them. But when he closed his eyes he saw it burning. The trees burning. The sea rising up in steam.

Go back four years. Marith sits in his new-built fortress of Ethalden, new-crowned King of the White Isles and Ith and the Wastes and Illyr. He has taken his father’s kingdom. Yes, well, any number of sons have done that. He has taken the neighbouring kingdom. That’s not exactly novel behaviour from a new ambitious young king with his people to impress. He has taken the kingdom of his holy ancestors, he is a king returned in glory, he has restored a blighted land to greatness, he has been revenged on the evil-doers who ill-treated him. That’s absolutely right and proper. Expected by everyone. And then …

‘Gods, this is glorious,’ Osen Fiolt says one night in the new-built fortress of Ethalden, as they sit together in a feasting hall with walls and floor and ceiling of solid gold. ‘Goodbye sleeping in a stinking tent in the pissing rain. Hello sitting by the fire with our feet up. We’re richer than gods and worshipped like gods and we’ve still got our whole lives ahead of us to do absolutely nothing but enjoy ourselves in.

‘Look at my hands,’ Osen says, stretching out his right hand. ‘Look, the calluses are finally going down. I might grow a beard, you know? Befitting my noble status as First Lord of Illyr. Or get my wife pregnant. You’re going to have a child, Marith, you should maybe grow a beard as well. Dress like a respectable family man, stop wearing all black. Kings wear long robes, have well-combed beards, feast and wench rather than drink and mope. Those pretentious boys quoting godsawful poetry and weeping over life’s burden … and now we’ve got wives and children and kingdoms to rule. Gods, who’d have thought?

‘I will do nothing,’ Osen says, ‘but sit by the fire and drink the finest wines and eat the choicest meats and fuck my wife and my servants. Raise a horde of spoilt brat children. Never pick up a sword again.’

‘It feels strange walking,’ Marith says, ‘without a sword at my hip. Unbalanced.’

‘Lighter,’ Osen says. ‘Much lighter. The joys of not wearing armour! A real spring in my step.’

‘That too.’

They both go to bed early, dozy with warmth. It’s very restful, doing nothing. It’s amazing how tiring paperwork and bureaucracy and helping your wife choose baby things can be. He goes to bed early, wakes late in a warm room in a bed of gold and ivory and red velvet, soft as thistledown after campaign beds. His bedchamber looks very much like the one he slept in at Malth Salene. He is not sure whether Thalia realizes this. Unlike at Malth Salene, the morning sun shines in on his face. He tries to put this thing he feels into words; even to himself he cannot say what it is.

Two days later he is reviewing the Army of Amrath. Dismissing most of it. Illyr is taken. The Wastes are taken. Ith is taken. The White Isles were and are his own. He is king. War is done. All is at peace.

‘You have to disband some of them,’ Lord Nymen the Fishmonger says to him. ‘They are driving the people of Ethalden mad with their brawling, the women fear to walk the streets after dark because of them, innkeeps and merchants shut up shop at a soldier’s approach. As they say: a friendly army without a purpose is more dangerous than an enemy army at the gates. Also, more seriously, My Lord King – do you know how much this army costs?’

‘I have the wealth of three kingdoms at my feet.’

There is a short pause. ‘You had the wealth of three kingdoms at your feet, My Lord King,’ Aris Nymen says.

A thousand times a thousand soldiers. And horses. And armour. And equipment. And engineers and doctors and weaponsmiths and farriers and grooms and camp servants and carters and …

‘Yes, yes, I suppose. I see. Yes.’

‘The cost of Queen Thalia’s temple, My Lord King … It being made of solid gold … Amrath’s tomb … The work on the harbour is proving more expensive than we thought …’

‘Hang the man who thought up the original cost then. No. No. I’m joking. You’re right.’ I am King of Illyr and Ith and the Wastes and the White Isles. I am invincible, invulnerable, soon I will have a strong son to follow me. What am I afraid of, that I need an army of a thousand times a thousand men? He rubs his eyes. For the first time since he took Illyr, he does not sleep well. He stands in the great courtyard in Ethalden, raised up before his army on a dais of sweetwood hung with silver cloth. They cheer him. They hold out their hands to him. Their faces shine with love.

‘Amrath! Amrath! Amrath! King Marith!’

He smiles, basking in it. They shine so brightly, his soldiers, so strong, so proud. He begins to speak.

Stirring. Faces grow pale. Eyes stare up at him in astonishment.

The war is over. They have won eternal glory, until the drowning of the world the poets will sing of them. They can go home now in triumph to their friends and families, tell them of their prowess, show them the riches they have won. If they do not want to go home they can have land in Illyr, slaves to work it, a life of leisure, farming: the soil in Illyr now is rich and good. That is what all men want, isn’t it? A house, a garden in which children are playing, fruit trees, clear sweet water, fresh meat, fresh bread. Long days of peace stretch before them. They are heroes from the poems, every one of them. They will look back on what they have done with pride all their lives.

Muttering. Whispering. He can see tears on some of their faces, at the thought of this time ending. Feels tears himself, to dismiss them. They who have made him all he is. He hears his voice unwinding out of his mouth.

Their voices come back mournful as seabirds: ‘But … But … My Lord King …’ ‘You can’t … you cannot abandon us, Lord King …’ ‘We fought for you. We shed our own blood for you. You can’t abandon us. Please, Lord King, do not abandon us to live away from you.’ ‘We are the Army of Amrath! You are our king! Without this, we are … we are nothing.’ ‘Please! Please, Lord King!’

It feels … shameful, and sad, and delicious.

‘A farm?’ a voice shouts, bitter, croaking, it sounds like a raven cawing, like one of the old women who sell meat in the army’s camp. ‘A farm? What do we want with farming?’

‘What about our pay?’ a voice shouts. ‘Never mind bloody poetry. We’re two months’ pay in arrears, Lord King!’

There is something in that voice he has not heard for a long time. ‘Prince Ruin. Gods, you stink.’ ‘You’re disgusting, Marith, look at the state of you, how can you do this to me? To your father? Look what you’re doing to him.’

‘What about our pay? Yes!’

A great roar, like the waves when the tide is high and the storm wind is blowing, wave crashing against wave: ‘What about our pay, you cheap bastard? Pay us!’ ‘You can’t abandon us! You are our king! Don’t abandon us!’ ‘Pay us, you cheap bastard shit!’ A voice shouts, ‘Pension us off, will you? Who made you all this, eh? Who made you king?’ ‘You’ve got a fucking palace!’ a voice shouts. ‘What have we got?’ ‘You can’t abandon us,’ a voice shouts. ‘You owe us. We made you king.’

He looks down on his army who have conquered three kingdoms for him, and a great fear takes him.

‘You will have all that you are owed. Those who wish to remain here in Illyr will have land to farm. Those who wish to go home to their families I will provide with passage.’ His voice is shaking. His hand goes to the hilt of his sword. ‘You are dismissed.’ A few of them still jeer. Dogs’ faces, snarling at him. Many of them stand openly weeping. Frozen. The tears on their faces look like snowflakes. ‘You are dismissed,’ he shouts at them. He walks down from the dais away from them into his palace. His back is turned to them inviting a sword blade between his shoulders. He can almost, almost feel one of them stabbing a sword blade into him. No one dares to go near him: they see his eyes, they see the shadows around him, they hear the shadows scream in triumph. If he had dismissed them after he took Malth Tyrenae. After he took Malth Elelane. If they had never crowned him king … They howl and moan behind him, prayers, entreaties, curses, ‘Amrath,’ they beg him, ‘Amrath. You cannot do this to us.’ ‘They are dismissed,’ he shouts to Osen Fiolt and Alis Nymen. ‘Dismissed.’

Thalia looks at him with sorrow. ‘They don’t mean it, Marith. They have shed their blood for you. Of course they are upset.’ She says, ‘They will be glad enough soon, when they have got back home safe to their families.’ She is pregnant, soon he will have a family. ‘We marched all across the Wastes with them,’ she says, putting her arms around him as she will soon put her arms around their son. ‘They suffered for us. They shared in our glory, crowned us, celebrated victory with us. I feel sad myself,’ she says, ‘to see this ending, to be dismissing them after everything they have done for us. But we will be glad of it,’ she says, ‘and they will be. When we have our son and they have their homes and their families around them.’

Yes: he thinks of his own father King Illyn, running with him in the gardens of Malth Elelane, his father’s stern face creased up with laughing. ‘Catch me, Daddy!’ ‘Caught you, Marith! Caught you!’ He walks up and down in his chambers, trying to block out the sound of their voices, cursing them.

‘Leave them,’ Thalia says, ‘Marith. Look,’ her face changes, ‘look, Marith,’ she says suddenly, ‘they are beginning to disperse.’

‘They are?’ He comes to the window to join her. It is coming on to evening, growing colder, the smell of their evening meal cooking hangs warm in the air. It is true, they are beginning to drift away, more and more of them. Their shouts are fading. The courtyard cannot be more than half full.

‘I told you they would,’ Thalia says. Her voice too is almost regretful. ‘They suffered so much for us,’ she says. ‘Pay them double, Marith, when you send them off.’