Полная версия

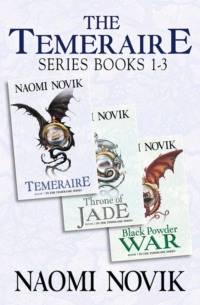

Temeraire

He had always entertained a certain private longing for a home of his own, imagined in detail through the long, lonely nights at sea: smaller by necessity than the one in which he had been raised, yet still elegant; kept by a wife whom he could trust with the management of their affairs and their children both; a comfortable refuge when he was at home, and a warm memory while at sea.

Every feeling protested against the sacrifice of this dream; yet under the circumstances, he was not even sure he could honourably make Edith an offer which she might feel obliged to accept. And there was no question of courting someone else in her place; no woman of sense and character would deliberately engage her affections on an aviator, unless she was of the sort who preferred to have a complacent and absent husband leaving his purse in her hands, and to live apart from him even while he was in England; such an arrangement did not appeal to Laurence in the slightest.

The sleeping dragon, swaying back and forth in his cot, tail twitching unconsciously in time with some alien dream, was a very poor substitute for hearth and home. Laurence stood and went to the stern windows, looking over the Reliant’s wake, a pale and opalescent froth streaming out behind her in the light from the lanterns; the ebb and flow was pleasantly numbing to watch.

His steward Giles brought in his dinner with a great clatter of plate and silver, keeping well back from the dragon’s cot. His hands trembled as he laid out the service; Laurence dismissed him once the meal was served and sighed a little when he had gone; he had thought of asking Giles to come along with him, as he supposed even an aviator might have a servant, but there was no use if the man was spooked by the creatures. It would have been something to have a familiar face.

In solitude, he ate his simple dinner quickly; it was only salt beef with a little glazing of wine, as the fish had gone into Temeraire’s belly, and he had little appetite in any case. He tried to write some letters, afterwards, but it was no use; his mind would wander back into gloomy paths, and he had to force his attention to every line. At last he gave it up, looked out briefly to tell Giles he would take no supper this evening, and climbed into his own cot. Temeraire shifted and snuggled deeper within the bedding; after a brief struggle with uncharitable resentment, Laurence reached out and covered him more securely, the night air being somewhat cool, and then fell asleep to the sound of his regular deep breathing, like the heaving of a bellows.

Chapter Two

The next morning Laurence woke when Temeraire proceeded to envelop himself in his cot, which turned around twice as he tried to climb down. Laurence had to unhook it to disentangle him, and he burst out of the unwound fabric in hissing indignation. He had to be groomed and petted back into temper, like an affronted cat, and then he was at once hungry again.

Fortunately, it was not very early, and the hands had met with some luck fishing, so there were still eggs for his own breakfast, the hens being spared another day, and a forty-pound tunny for the dragon’s. Temeraire somehow managed to devour the entire thing and then was too heavy to get back into his cot, so he simply dropped in a distended heap upon the floor and slept there.

The rest of the first week passed similarly: Temeraire was asleep except when he was eating, and he ate and grew alarmingly. By the end of it, he was no longer staying below, because Laurence had grown to fear that it would become impossible to get him out of the ship: he had already grown heavier than a carthorse, and longer from tip to tail than the launch. After consideration of his future growth, they decided to shift stores to leave the ship heavier forward and place him upon the deck towards the stern as a counterbalance.

The change was made just in time: Temeraire only barely managed to squeeze back out of the cabin with his wings furled tightly, and he grew another foot in diameter overnight by Mr. Pollitt’s measurements. Fortunately, when he lay astern his bulk was not greatly in the way, and there he slept for the better part of each day, tail twitching occasionally, hardly stirring even when the hands were forced to clamber over him to do their work.

At night, Laurence slept on deck beside him, feeling it his place; as the weather held fair, it cost him no great pains. He was increasingly worried about food; the ox would have to be slaughtered in a day or so, with all the fishing they could do. At this rate of increase in his appetite, even if Temeraire proved willing to accept cured meat, he might exhaust their supplies before they reached shore. It would be very difficult, he felt, to put a dragon on short commons, and in any case it would put the crew on edge; though Temeraire was harnessed and might be in theory tame, even in these days a feral dragon, escaped from the breeding grounds, could and occasionally would eat a man if nothing more appetizing offered; and from the uneasy looks no one had forgotten it.

When the first change in the air came, midway through the second week, Laurence felt the alteration unconsciously and woke near dawn, some hours before the rain began to fall. The lights of the Amitié were nowhere to be seen: the ships had drawn apart during the night, under the increasing wind. The sky grew only a little lighter, and presently the first thick drops began to patter against the sails.

Laurence knew that he could do nothing; Riley must command now, if ever, and so Laurence set himself to keeping Temeraire quiet and no distraction to the men. This proved difficult, for the dragon was very curious about the rain, and kept spreading his wings to feel the water beating upon them.

Thunder did not frighten him, nor lightning; ‘What makes it?’ he only asked, and was disappointed when Laurence could offer him no answer. ‘We could go and see,’ he suggested, partly unfolding his wings again, and taking a step towards the stern railing. Laurence started with alarm; Temeraire had made no further attempts to fly since the first day, being more pre occupied with eating, and though they had enlarged the harness three times, they had never exchanged the chain for a heavier one. Now he could see the iron links straining and beginning to come open, though Temeraire was barely exerting any pull upon it.

‘Not now, Temeraire, we must let the others work, and watch from here,’ he said, gripping the nearest side-strap of the harness and thrusting his left arm through it; though he realized now, too late, that his weight would no longer be an impediment, at least if they went aloft together, he might be able to persuade the dragon to come back down eventually. Or he might fall; but that thought he pushed from his mind as quickly as it came.

Thankfully, Temeraire settled again, if regretfully, and returned to watching the sky. Laurence looked about with a faint idea of calling for a stronger chain, but the crew were all occupied, and he could not interrupt. In any case, he wondered if there were any on board that would serve as more than an annoyance; he was abruptly aware that Temeraire’s shoulder topped his head by nearly a foot, and that the foreleg which had once been as delicate as a lady’s wrist was now thicker around than his thigh.

Riley was shouting through the speaking-trumpet to issue his orders. Laurence did his best not to listen; he could not intervene, and it could only be unpleasant to hear an order he did not like. The men had already been through one nasty gale as a crew and knew their work; fortunately the wind was not contrary, so they might go scudding before the gale, and the topgallant masts had already been struck down properly. So far all was well, and they were keeping roughly on their eastern heading, but behind them an opaque curtain of whirling rain blotted out the world, and it was outpacing the Reliant.

The wall of water crashed upon the deck with the sound of gunfire, soaking him through to the skin immediately despite his oilskin and sou’wester. Temeraire snorted and shook his head like a dog, sending water flying, and ducked down beneath his own hastily opened wings, which he curled about himself. Laurence, still tucked up against his side and holding to the harness, found himself also sheltered by the living dome. It was exceedingly strange to be so snug in the heart of a raging storm; he could still see out through the places where the wings did not overlap, and a cool spray came in upon his face.

‘That man who brought me the shark is in the water,’ Temeraire said presently, and Laurence followed his line of sight; through the nearly solid mass of rain he could see a blur of red and white shirt some six points abaft the larboard beam, and something like an arm waving: Gordon, one of the hands who had been helping with the fishing.

‘Man overboard,’ he shouted, cupping his hands around his mouth to make it carry, and pointed out to the struggling figure in the waves. Riley gave one anguished look; a few ropes were thrown, but already the man was too far back; the storm was blowing them before it, and there was no chance of retrieving him with the boats.

‘He is too far from those ropes,’ Temeraire said. ‘I will go and get him.’

Laurence was in the air and dangling before he could object, the broken chain swinging free from Temeraire’s neck beside him. He seized it with his loose arm as it came close and wrapped it around the straps of the harness a few times to keep it from flailing and striking Temeraire’s side like a whip; then he clung grimly and tried only to keep his head, while his legs hung out over empty air with nothing but the ocean waiting below to receive him if he should lose his grip.

Instinct had sufficed to get them aloft, but it might not be adequate to keep them there; Temeraire was being forced to the east of the ship. He kept trying to fight the wind head on; there was a hideous dizzying moment where they went tumbling before a sharp gust, and Laurence thought for an instant that they were lost and would be dashed into the waves.

‘With the wind,’ he roared with every ounce of breath developed over eighteen years at sea, hoping Temeraire could hear him. ‘Go with the wind, damn you!’

The muscles beneath his cheek strained, and Temeraire righted himself, turning eastwards. Abruptly the rain stopped beating upon Laurence’s face: they were flying with the wind, going at an enormous rate. He gasped for breath, tears whipping away from his eyes with the speed; he had to close them. It was as far beyond standing in the tops at ten knots as that experience was beyond standing in a field on a hot, still day. There was a reckless laughter trying to bubble out of his throat, like a boy’s, and he only barely managed to stifle it and think sanely.

‘We cannot come straight at him,’ he called. ‘You must tack – you must go to north, then south, Temeraire, do you understand?’

If the dragon answered, the wind took the reply, but he seemed to have grasped the idea. He dropped abruptly, angling northwards with his wings cupping the wind; Laurence’s stomach dived as on a rowboat in a heavy swell. The rain and wind still battered them, but not so badly as before, and Temeraire came about and changed tacks as sweetly as a fine cutter, zigzagging through the air and making gradual progress back in a westerly direction.

Laurence’s arms were burning; he thrust his left arm through the breastband against losing his grip, and unwound his right hand to give it a respite. As they drew even with and then passed the ship, he could just see Gordon still struggling in the distance; fortunately the man could swim a little, and despite the fury of the rain and wind, the swell was not so great as to drag him under. Laurence looked at Temeraire’s claws dubiously; with the enormous talons, if the dragon were to snatch Gordon up, the manoeuvre might as easily kill the man as save him. Laurence would have to put himself into position to catch Gordon.

‘Temeraire, I will pick him up; wait until I am ready, then go as low as you can,’ he called; then lowered himself down the harness slowly and carefully to hang down from the belly, keeping one arm hooked through a strap at every stage. It was a terrifying progress, but once he was below, matters became easier, as Temeraire’s body shielded him from the rain and wind. He pulled on the broad strap that ran around Temeraire’s middle; there was perhaps just enough give. One at a time he worked his legs between the leather and Temeraire’s belly, so he might have both his hands free, then slapped the dragon’s side.

Temeraire stooped abruptly, like a diving hawk. Laurence let himself dangle down, trusting to the dragon’s aim, and his fingers made furrows in the surface of the water for a couple of yards before they hit sodden cloth and flesh. He blindly clutched at the feel, and Gordon grabbed at him in turn. Temeraire was lifting back up and away, wings beating furiously, but thankfully they could now go with the wind instead of fighting it. Gordon’s weight dragged on Laurence’s arms, shoulders, thighs, every muscle straining; the band was so tight upon his calves that he could no longer feel his legs below the knee, and he had the uncomfortable sensation of all the blood in his body rushing straight into his head. They swung heavily back and forth like a pendulum as Temeraire arrowed back towards the ship, and the world tilted crazily around him.

They dropped onto the deck ungracefully, rocking the ship. Temeraire stood wavering on his hind legs, trying at the same time to fold his wings out of the wind and keep his balance with the two of them dragging him downwards from the belly-strap. Gordon let go and scrambled away in panic, leaving Laurence to extract himself while Temeraire seemed about to fall over upon him at any moment. His stiff fingers refused to work on the buckles, and abruptly Wells was there with a knife flashing, cutting through the strap.

His legs thumped heavily to the deck, blood rushing back into them; Temeraire similarly dropped down to all fours again beside him, the impact sending a tremor through the deck. Laurence lay flat on his back and panted, not caring for the moment that rain was beating full upon him; his muscles would obey no command. Wells hesitated; Laurence waved him back to his work and struggled back onto his legs; they held him up, and the pain of the returning sensation eased as he forced them to move.

The gale was still blowing around them, but the ship was now set to rights, scudding before the wind under close-reefed topsails, and there was less of a feel of crisis upon the deck. Turning away from Riley’s handiwork with a sense of mingled pride and regret, Laurence coaxed Temeraire to shift back towards the centre of the stern where his weight would not unbalance the ship. It was barely in time; as soon as Temeraire settled down once again, he yawned enormously and tucked his head down beneath his wing, ready to sleep for once without making his usual demand for food. Laurence slowly lowered himself to the deck and leaned against the dragon’s side; his body still ached profoundly from the strain.

He roused himself for only a moment longer; he felt the need to speak, though his tongue felt thick and stupid with fatigue. ‘Temeraire,’ he said, ‘that was well done. Very bravely done.’

Temeraire brought his head out and gazed at him, eyeslits widening to ovals. ‘Oh,’ he said, sounding a little uncertain. Laurence realized with a brief stab of guilt that he had scarcely given the dragonet a kind word before this. The convulsion of his life might be the creature’s fault, in some sense, but Temeraire was only obeying his nature, and to make the beast suffer for it was hardly noble.

But he was too tired at the moment to make better amends than to repeat, lamely, ‘Very well done,’ and pat the smooth black side. Yet it seemed to serve; Temeraire said nothing more, but he shifted himself a little and tentatively curled up around Laurence, partly unfurling a wing to shield him from the rain. The fury of the storm was muffled beneath the canopy, and he could feel the great heartbeat against his cheek; he was warmed through in moments by the steady heat of the dragon’s body, and thus sheltered he slid abruptly and completely into sleep.

‘Are you quite sure it is secure?’ Riley asked, anxiously. ‘Sir, I am sure we could put together a net, perhaps you had better not.’

Laurence shifted his weight and pulled against the straps wrapped snugly around his thighs and calves; they did not give, nor did the main part of the harness, and he remained stable in his perch atop Temeraire’s back, just behind the wings. ‘No, Tom, it won’t do, and you know it; this is not a fishing boat, and you cannot spare the men. We might very well meet a Frenchman one of these days, and then where would we be?’ He leaned forward and patted Temeraire’s neck; the dragon’s head was doubled back, observing the proceedings with interest.

‘Are you ready? May we go now?’ he asked, putting a forehand on the railing. Muscles were already gathering beneath the smooth hide, and there was a palpable impatience in his voice.

‘Stand clear, Tom,’ Laurence said hastily, casting off the chain and taking hold of the neck strap. ‘Very well, Temeraire, let us—’ A single leap, and they were airborne, the broad wings thrusting in great sweeping arcs to either side of him, the whole long body stretched out like an arrow driving upwards into the sky. He looked downwards over Temeraire’s shoulder; already the Reliant was shrinking to a child’s toy, bobbing lonely in the vast expanse of the ocean; he could even see the Amitié perhaps twenty miles to the east. The wind was enormous, but the straps were holding, and he was grinning idiotically again, he realized, unable to prevent himself.

‘We will keep to the west, Temeraire,’ Laurence called; he did not want to run the risk of getting too close to land and possibly encountering a French patrol. They had put a band around the narrow part of Temeraire’s neck beneath the head and attached reins to this, so Laurence might more easily give Temeraire direction; now he consulted the compass he had strapped into his palm and tugged on the right rein. The dragon pulled out of his climb and turned willingly, levelling out. The day was clear, without clouds, and a moderate swell only; Temeraire’s wings beat less rapidly now they were no longer going up, but even so the pace was devouring the miles: the Reliant and the Amitié were already out of sight.

‘Oh, I see one,’ Temeraire said, and they were plummeting down with even more speed. Laurence gripped the reins tightly and swallowed down a yell; it was absurd to feel so childishly gleeful. The distance gave him some more idea of the dragon’s eyesight: it would have to be prodigious to allow him to sight prey at such a range. He had barely time for the thought, then there was a tremendous splash, and Temeraire was lifting back away with a porpoise struggling in his claws and streaming water.

Another astonishment: Temeraire stopped and hovered in place to eat, his wings beating perpendicular to his body in swivelling arcs; Laurence had had no idea that dragons could perform such a manoeuvre. It was not comfortable, as Temeraire’s control was not very precise and he bobbed up and down wildly, but it proved very practical, for as he scattered bits of entrails onto the ocean below, other fish began to rise to the surface to feed on the discards, and when he had finished with the porpoise he at once snatched up two large tunnys, one in each forehand, and ate these as well, and then an immense swordfish also.

Having tucked his arm under the neck strap to keep himself from being flung about, Laurence was free to look around himself and consider the sensation of being master of the entire ocean, for there was not another creature or vessel in sight. He could not help but feel pride in the success of the operation, and the thrill of flying was extra ordinary: so long as he could enjoy it without thinking of all it was to cost him, he could be perfectly happy.

Temeraire swallowed the last bite of the swordfish and discarded the sharp upper jaw after inspecting it curiously. ‘I am full,’ he said, beating back upwards into the sky. ‘Shall we go and fly some more?’

It was a tempting suggestion; but they had been aloft more than an hour, and Laurence was not yet sure of Temeraire’s endurance. He regretfully said, ‘Let us go back to the Reliant, and if you like we may fly a bit more about her.’

And then racing across the ocean, low to the waves now, with Temeraire snatching at them playfully every now and again; the spray misting his face and the world rushing by in a blur, but for the constant solid presence of the dragon beneath him. He gulped deep draughts of the salt air and lost himself in simple enjoyment, only pausing every once and again to tug the reins after consulting his compass, and bringing them at last back to the Reliant.

Temeraire said he was ready to sleep again after all, so they made a landing; this time it was a more graceful affair, and the ship did not bounce so much as settle slightly lower in the water. Laurence unstrapped his legs and climbed down, surprised to find himself a little saddlesore; but he at once realized that this was only to be expected. Riley was hurrying back to meet them, relief written clearly on his face, and Laurence nodded to him reassuringly.

‘No need to worry; he did splendidly, and I think you need not worry about his meals in future: we will manage very well,’ he said, stroking the dragon’s side; Temeraire, already drowsing, opened one eye and made a pleased rumbling noise, then closed it again.

‘I am very glad to hear it,’ Riley said, ‘and not least because that means our dinner for you tonight will be respectable: we took the precaution of continuing our efforts in your absence, and we have a very fine turbot which we may now keep for ourselves. With your consent, perhaps I will invite some members of the gunroom to join us.’

‘With all my heart; I look forward to it,’ Laurence said, stretching to relieve the stiffness in his legs. He had insisted on surrendering the main cabin once Temeraire had been shifted to the deck; Riley had at last acquiesced, but he compensated for his guilt at displacing his former captain by inviting Laurence to dine with him virtually every night. This practice had been interrupted by the gale, but that having blown itself out the night before, they meant to resume this evening.

It was a good meal and a merry one, particularly once the bottle had gone round a few times and the younger midshipmen had drunk enough to lose their wooden manners. Laurence had the happy gift of easy conversation, and his table had always been a cheerful place for his officers; to help matters along further, he and Riley were fast approaching a true friendship now that the barrier of rank had been removed.

The gathering thus had an almost informal flavour to it, so that when Carver found himself the only one at liberty, having devoured his pudding a little more quickly than his elders, he dared to address Laurence directly, and tentatively said, ‘Sir, if I may be so bold as to ask, is it true that dragons can breathe fire?’

Laurence, pleasantly full of plum duff topped by several glasses of a fine Riesling, received the question tolerantly. ‘That depends upon the breed, Mr. Carver,’ he answered, putting down his glass. ‘However, I think the ability extremely rare. I have only ever seen it once myself: in a Turkish dragon at the battle of the Nile, and I was damned glad the Turks had taken our part when I saw it work, I can tell you.’

The other officers shuddered all around and nodded; few things were as deadly to a ship as uncontrolled fire upon her deck. ‘I was on the Goliath myself,’ Laurence went on. ‘We were not half a mile distant from the Orient when she went up, like a torch; we had shot out her deck-guns and mostly cleared her sharpshooters from the tops, so the dragon could strafe her at will.’ He fell silent, remembering; the sails all ablaze and trailing thick plumes of black smoke; the great orange-and-black beast diving down and pouring still more fire from its jaws upon them, its wings fanning the flames; the terrible roaring that was only drowned out at last by the explosion, and the way all sound had been muted for nearly a day thereafter. He had been in Rome once as a boy, and there seen in the Vatican a painting of Hell by Michelangelo, with dragons roasting the damned souls with fire; it had been very like.