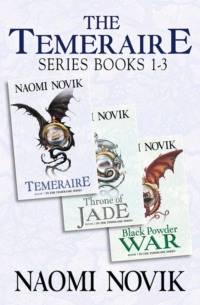

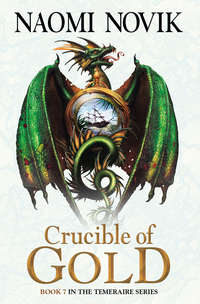

Temeraire

Полная версия

Temeraire

Жанр: фэнтезизарубежная фантастикакниги о войнесовременная зарубежная литературазарубежное фэнтезиисторическое фэнтезигероическое фэнтезисерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу