Полная версия

Temeraire

‘You are very kind, sir,’ Laurence said formally, bowing. The compliment had not been a natural one, but he could see that the rest of the remark was meant sincerely enough, and it made perfect sense. Certainly Temeraire would do better in the hands of a trained aviator, a fellow who would handle him properly, the same way a ship would do better in the hands of a real seaman. It had been wholly an accident that Temeraire had been settled upon him, and now that he knew the truly extraordinary nature of the dragon, it was even more obvious that Temeraire deserved a partner with an equal degree of skill. ‘Of course you would prefer a trained man in the position if at all possible, and I am happy if I have been of any service. Shall I take Mr. Dayes to Temeraire now?’

‘No!’ Dayes said sharply, only to fall silent at a look from Portland.

Portland answered more politely, ‘No, thank you, Captain; on the contrary, we prefer to proceed exactly as if the dragon’s handler had died, to keep the procedure as close as possible to the set methods which we have devised for accustoming the creature to a new handler. It would be best if you did not see the dragon again at all.’

That was a blow. Laurence almost argued, but in the end he closed his mouth and only bowed again. If it would make the process of transition easier, it was only his duty to keep away.

Still, it was very unpleasant to think of never seeing Temeraire again; he had made no fare well, said no last kind words, and to simply stay away felt like a desertion. Sorrow weighed on him heavily as he left the Commendable, and it had not dissipated by evening; he was meeting Riley and Wells for dinner, and when he came into the parlour of the hotel where they were waiting for him, it was an effort to give them a smile and say, ‘Well, gentlemen, it seems you are not to be rid of me after all.’

They looked surprised; shortly they were both congratulating him enthusiastically, and toasting his freedom. ‘It is the best news I have heard in a fortnight,’ Riley said, raising a glass. ‘To your health, sir.’ He was very clearly sincere despite the promotion it would likely cost him, and Laurence was deeply affected; consciousness of their true friendship lifted the grief at least a little, and he was able to return the toast with something approaching his usual demeanour.

‘It does seem they went about it rather strangely, though,’ Wells said a little later, frowning over Laurence’s brief description of the meeting. ‘Almost like an insult, sir, and to the Navy, too; as though a naval officer were not good enough for them.’

‘No, not at all,’ Laurence said, although privately he did not feel very sure of his interpretation. ‘Their concern is for Temeraire, I am sure, and rightly so, as well as for the Corps; one could scarcely expect them to be glad at the prospect of having an untrained fellow on the back of so valuable a creature, any more than we would like to see an Army officer given command of a first-rate.’

So he said, and so he believed, but that was not very much of a consolation. As the evening wore on, he grew more rather than less conscious of the grief of parting, despite the companionship and the good food. It had already become a settled habit with him to spend the nights reading with Temeraire, or talking to him, or sleeping by his side, and this sudden break was painful. He knew that he was not perfectly concealing his feelings; Riley and Wells gave him anxious glances as they talked more to cover his silences, but he could not force himself to a feigned display of happiness which would have reassured them.

The pudding had been served and he was making an attempt to get some of it down when a boy came running in with a note for him: it was from Captain Portland; he was asked in urgent terms to come to the cottage. Laurence started up from the table at once, barely making a few words of explanation, and dashed out into the street without even waiting for his overcoat. The Madeira night was warm, and he did not mind the lack, particularly after he had been walking briskly for a few minutes; by the time he reached the cottage he would have been glad of an excuse to remove his neckcloth.

The lights were on inside; he had offered the use of the establishment to Captain Portland for their convenience, as it was near the field. When Fernao opened the door for him he came in to find Dayes with his head in his hands at the dinner table, surrounded by several other young men in the uniform of the Corps, and Portland standing by the fireplace and gazing into it with a rigid, disapproving expression.

‘Has something happened?’ Laurence asked. ‘Is Temeraire ill?’

‘No,’ Portland said shortly, ‘he has refused to accept the replacement.’

Dayes abruptly pushed up from the table and took a step towards Laurence. ‘It is not to be borne! An Imperial in the hands of some untrained Navy clodpole—’ he cried. He was stifled by his friends before anything more could escape him, but the expression had still been shockingly offensive, and Laurence at once gripped the hilt of his sword.

‘Sir, you must answer,’ he said angrily, ‘that is more than enough.’

‘Stop that; there is no duelling in the Corps,’ Portland said. ‘Andrews, for God’s sake put him to bed and get some laudanum into him.’ The young man restraining Dayes’s left arm nodded, and he and the other three pulled the struggling lieutenant out of the room, leaving Laurence and Portland alone, with Fernao standing wooden-faced in the corner still holding a tray with the port decanter upon it.

Laurence wheeled on Portland. ‘A gentleman cannot be expected to tolerate such a remark.’

‘An aviator’s life is not only his own; he cannot be allowed to risk it so pointlessly,’ Portland said flatly. ‘There is no duelling in the Corps.’

The repeated pronouncement had the weight of law, and Laurence was forced to see the justice in it; his hand relaxed minutely, though the angry colour did not leave his face. ‘Then he must apologize, sir, to myself and to the Navy; it was an outrageous remark.’

Portland said, ‘And I suppose you have never made nor listened to equally outrageous remarks made about aviators, or the Corps?’

Laurence fell silent before the open bitterness in Portland’s voice. It had never before occurred to him that aviators themselves would surely hear such remarks and resent them; now he understood still more how savage that resentment must be, given that they could not even make answer by the code of their service. ‘Captain,’ he said at last, more quietly, ‘if such remarks have ever been made in my presence, I may say that I have never been responsible for them myself, and where possible I have spoken against them harshly. I have never willingly heard disparaging words against any division of His Majesty’s armed forces; nor will I ever.’

It was now Portland’s turn to be silent, and though his tone was grudging, he did finally say, ‘I accused you unjustly; I apologize. I hope that Dayes, too, will make his apologies when he is less distraught; he would not have spoken so if he had not just suffered so bitter a disappointment.’

‘I understood from what you said that there was a known risk,’ Laurence said. ‘He ought not have built his expectations so high; surely he can expect to succeed with a hatchling.’

‘He accepted the risk,’ Portland said. ‘He has spent his right to promotion. He will not be permitted to make another attempt, unless he wins another chance under fire; and that is unlikely.’

So Dayes was in the same position which Riley had occupied before their last voyage, save perhaps with even less chance, dragons being so very rare in England. Laurence still could not forgive the insult, but he understood the emotion better; and he could not help feeling pity for the fellow, who was after all only a boy. ‘I see; I will be happy to accept an apology,’ he said; it was as far as he could bring himself to go.

Portland looked relieved. ‘I am glad to hear it,’ he said. ‘Now, I think it would be best if you went to speak to Temeraire; he will have missed you, and I believe he was not pleased to be asked to take on a replacement. I hope we may speak again tomorrow; we have left your bedroom untouched, so you need not shift for yourself.’

Laurence needed little encouragement; moments later he was striding to the field. As he drew near, he could make out Temeraire’s bulk by the light of the half-moon: the dragon was curled in small upon himself and nearly motionless, only stroking his gold chain between his foreclaws. ‘Temeraire,’ he called, coming through the gate, and the proud head lifted at once.

‘Laurence?’ he said; the uncertainty in his voice was painful to hear.

‘Yes, my dear,’ Laurence said, crossing swiftly to him, almost running at the end. Making a soft crooning noise deep in his throat, Temeraire curled both forelegs and wings around him and nuzzled him carefully; Laurence stroked the sleek nose.

‘He said you did not like dragons, and that you wanted to be back on your ship,’ Temeraire said, very low. ‘He said you only flew with me out of duty.’

Laurence went breathless with rage; if Dayes had been in front of him he would have flown at the man barehanded and beaten him. ‘He was lying, Temeraire,’ he said, with difficulty; he was half-choked by fury.

‘Yes; I thought he was,’ Temeraire said. ‘But it was not pleasant to hear, and he tried to take away my chain. It made me very angry. And he would not leave, until I put him out, and then you still did not come; I thought maybe he would keep you away, and I did not know where to go to find you.’

Laurence leaned forward and laid his cheek against the soft warm hide. ‘I am so very sorry,’ he said. ‘They persuaded me it was in your best interests to stay away and let him try; but I should have seen what kind of a fellow he was.’

Temeraire was quiet for several minutes, while they stood comfortably together, then said, ‘Laurence, I suppose I am too large to be on a ship now?’

‘Yes, pretty much, except for a dragon transport,’ Laurence said, lifting his head; he was puzzled by the question.

‘If you would like to have your ship back,’ Temeraire said, ‘I will let someone else ride me. Not him, because he says things that are not true; but I will not make you stay.’

Laurence stood motionless for a moment, his hands still on Temeraire’s head, with the dragon’s warm breath curling around him. ‘No, dear one,’ he said at last, softly, knowing it was only the truth. ‘I would rather have you than any ship in the Navy.’

Chapter Four

‘No, throw your chest out deeper, like so.’ Laetificat stood up on her haunches and demonstrated, the enormous barrel of her red and gold belly expanding as she breathed in.

Temeraire mimicked the motion; his expansion was less visually dramatic, as he lacked the vivid markings of the female Regal Copper and was of course less than a fifth of her size as yet, but this time he managed a much louder roar. ‘Oh, there,’ he said, pleased, dropping back down to four legs. The cows were all running around their pen in manic terror.

‘Much better,’ Laetificat said, and nudged Temeraire’s back approvingly. ‘Practice every time you eat; it will help along your lung capacity.’

‘I suppose it is hardly news to you how badly we need him, given how our affairs stand,’ Portland said, turning to Laurence; the two of them were standing by the side of the field, out of range of the mess the dragons were about to make. ‘Most of Bonaparte’s dragons are stationed along the Rhine, and of course he has been busy in Italy; that and our naval blockades are all that is keeping him from invasion. But if he gets matters arranged to his satisfaction on the Continent and frees up a few aerial divisions, we can say hail and farewell to the blockade at Toulon; we simply do not have enough dragons of our own here in the Med to protect Nelson’s fleet. He will have to withdraw, and then Villeneuve will go straight for the Channel.’

Laurence nodded grimly; he had been reading the news of Bonaparte’s movements with great alarm since the Reliant had put into port. ‘I know Nelson has been trying to lure the French fleet out to battle, but Villeneuve is not a fool, even if he is no seaman. An aerial bombardment is the only hope of getting him out of his safe harbour.’

‘Which means there is no hope, not with the forces we can bring to it at present,’ Portland said. ‘The Home Division has a couple of Longwings, and they might be able to do it; but they cannot be spared. Bonaparte would jump on the Channel fleet at once.’

‘Ordinary bombing would not do?’

‘Not precise enough at long range, and they have poisoned shrapnel guns at Toulon. No aviator worth a shilling would take his beast close to the fortifications.’ Portland shook his head. ‘No, but there is a young Longwing in training, and if Temeraire will be kind enough to hurry up and grow, then perhaps together they might shortly be able to take the place of Excidium or Mortiferus at the Channel, and even one of those two might be sufficient at Toulon.’

‘I am sure he will do everything in his power to oblige you,’ Laurence said, glancing over; the dragon in question was on his second cow. ‘And I may say that I will do the same. I know I am not the man you wished in this place, nor can I argue with the reasoning that would prefer an experienced aviator in so critical a role. But I hope that naval experience will not prove wholly useless in this arena.’

Portland sighed and looked down at the ground. ‘Oh, hell,’ he said. It was an odd response to make, but Portland looked anxious, not angry, and after a moment he added, ‘There is just no getting around it; you are not an aviator. If it were simply a question of skill or knowledge, that would mean difficulties enough, but—’ He stopped.

Laurence did not think, from the tone, that Portland meant to question his courage. The man had been more amiable this morning; so far, it seemed to Laurence that aviators simply took clannishness to an extreme, and once having admitted a fellow into their circle, their cold manners fell away. So he took no offence, and said, ‘Sir, I can hardly imagine where else you believe the difficulty might lie.’

‘No, you cannot,’ Portland said, uncommunicatively. ‘Well, and I am not going to borrow trouble; they may decide to send you somewhere else entirely, not to Loch Laggan. But I am running ahead of myself: the real point is that you and Temeraire must get to England for your training soonest; once you are there, Aerial Command can best decide how to deal with you.’

‘But can he reach England from here, with no place to stop along the way?’ Laurence asked, diverted by concern for Temeraire. ‘It must be more than a thousand miles; he has never flown further than from one end of the island to the other.’

‘Closer to two thousand, and no; we would never risk him so,’ Portland said. ‘There is a transport coming over from Nova Scotia; a couple of dragons joined our division from it three days ago, so we have its position pretty well fixed, and I think it is less than a hundred miles away. We will escort you to it; if Temeraire gets tired, Laetificat can support him for long enough to give him a breather.’

Laurence was relieved to hear the proposed plan, but the conversation made him aware how very unpleasant his circumstances would be until his ignorance was mended. If Portland had waved off his fears, Laurence would have had no way of judging the matter for himself. Even a hundred miles was a good distance; it would take them three hours or more in the air. But that at least he felt confident they could manage; they had flown the length of the island three times just the other day, while visiting Sir Edward, and Temeraire had not seemed tired in the least.

‘When do you propose leaving?’ he asked.

‘The sooner the better; the transport is headed away from us, after all,’ Portland said. ‘Can you be ready in half an hour?’

Laurence stared. ‘I suppose I can, if I have most of my things sent back to the Reliant for transport,’ he said dubiously.

‘Why would you?’ Portland said. ‘Laet can carry anything you have; we shan’t weigh Temeraire down.’

‘No, I only mean that my things are not packed,’ Laurence said. ‘I am used to waiting for the tide; I see I will have to be a little more beforehand with the world from now on.’

Portland still looked puzzled, and when he came into Laurence’s room twenty minutes later he stared openly at the sea chest that Laurence had turned to this new purpose. There had hardly been time to fill half of it; Laurence paused in the act of putting in a couple of blankets to take up the empty space at the top. ‘Is something wrong?’ he asked, looking down; the chest was not so large that he thought it would give Laetificat any difficulty.

‘No wonder you needed the time; do you always pack so carefully?’ Portland said. ‘Could you not just throw the rest of your things into a few bags? We can strap them on easily enough.’

Laurence swallowed his first response; he no longer needed to wonder why the aviators looked, to a man, rumpled in their dress; he had imagined it due to some advanced technique of flying. ‘No, thank you; Fernao will take my other things to the Reliant, and I can manage perfectly well with what I have here,’ he said, putting the blankets in; he strapped them down and made all fast, then locked the chest. ‘There; I am at your service now.’

Portland called in a couple of his midwingmen to carry the chest; Laurence followed them outside, and was witness, for the first time, to the operation of a full aerial crew. Temeraire and he both watched with interest from the side as Laetificat stood patiently under the swarming ensigns, who ran up and down her sides as easily as they hung below her belly or climbed upon her back. The boys were raising up two canvas enclosures, one above and one below; these were like small, lopsided tents, framed with many thin and flexible strips of metal. The front panels which formed the bulk of the tent were long and sloped, evidently to present as little resistance to the wind as possible, and the sides and back were made of netting.

The ensigns all looked to be below the age of twelve; the midwingmen ranged more widely, just as aboard a ship, and now four older ones came staggering with the weight of a heavy leather-wrapped chain they dragged in front of Laetificat. The dragon lifted it herself and laid it over her withers, just in front of the tent, and the ensigns hurried to secure it to the rest of the harness with many straps and smaller chains.

Using this strap, they then slung a sort of hammock made of chain links beneath Laetificat’s belly. Laurence saw his own chest tossed inside along with a collection of other bags and parcels; he winced at the haphazard way in which the baggage was stowed, and was doubly grateful that he had been careful in his packing: he was confident they might turn his chest completely about a dozen times without casting his things into disarray.

A large pad of leather and wool, perhaps the thickness of a man’s arm, was laid on top of all, then the hammock’s edges were drawn up and hooked to the harness as widely as possible, spreading the weight of the contents and pressing them close to the dragon’s belly. Laurence felt a sense of dissatisfaction with the proceedings; he privately thought he would have to find a better arrangement for Temeraire, when the time came.

However, the process had one significant advantage over naval preparations: from beginning to end it took fifteen minutes, and then they were looking at a dragon in full light-duty rig. Laetificat reared up on her legs, shook out her wings, and beat them a half dozen times; the wind was strong enough to nearly stagger Laurence, but the assembled baggage did not shift noticeably.

‘All lies well,’ Laetificat said, dropping back down to all fours; the ground shook with the impact.

‘Lookouts aboard,’ Portland said; four ensigns climbed on and took up positions at the shoulders and hips, above and below, hooking themselves onto the harness. ‘Topmen and bellmen.’ Now two groups of eight midwingmen climbed up, one going into the tent above, the other below: Laurence was startled to perceive how large the enclosures really were; they seemed small only by virtue of comparison to Laetificat’s immense size.

The crews were followed in turn by the twelve riflemen, who had been checking and arming their guns while the others rigged out the gear. Laurence noticed Lieutenant Dayes leading them, and frowned; he had forgotten about the fellow in the rush. Dayes had offered no apology; now most likely they would not see one another for a long time. Although perhaps it was for the best; Laurence was not sure that he could have accepted the apology, after hearing Temeraire’s story, and as it was impossible to call the fellow out, the situation would have been uncomfortable to say the least.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

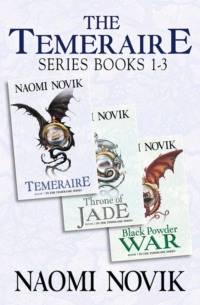

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.