полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol. 6, No 2, August, 1864

But should it happen—which fortunately is not a reasonable surmise—that the objects of this year's campaign should not be attained, we consider that the Southern confederacy exists only in pretence. Should its ports be to-day opened, should our armies fall back to their primary bases of operation, should European Powers formally declare that a slave republic exists, yet the new nation would be practically a nonentity. Does any one suppose that the United States would yield Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, Arkansas, New Orleans, and the Mississippi; that the freemen of Western Virginia would be forsaken; that Fortress Monroe and Port Royal would be abandoned? How long would a nation so surrounded, so intersected, exist, or how could it achieve any prosperity, character, and stability? Constant war, in the effort to expand and perfect its borders, would be its necessity; but such a necessity would be its destruction. There is no possibility of compromise or arrangement in the contest in which we are engaged, except with the parallel of the Potomac and the Ohio as the dividing border; but such an arrangement is impossible; entire reconquest becomes the imperative; it may be delayed, our present hopes may be disappointed, but the march of our armies thus far has trodden out the life from the Southern attempt at independence, and any future existence it may have will be merely muscular paroxysms—not the steady, regular, automatic movements of freedom and spontaneity.

Any notice of the operations of our armies would be incomplete without tributes to the ability of commanders and the valor of our soldiers. In no previous period of the war have these been more strikingly exemplified. The capacity of man to endure and his ability to exert himself continuously without exhausting his energy, are very wonderful. The reader of military history is constantly struck with this, in perusing accounts of sieges and marches and battles. War is always accompanied with a host of terrors—exposures to heat, cold, and tempests, marches through swamps and snows, suffering by hunger and thirst and fatigue, lying with bleeding wounds for days and nights between the lines of friends and foes, toil, danger, privation, pain, in every form. But among the memorable campaigns in the history of war, none is more marked for its incessant activity and the cheerful alacrity with which every hardship was endured, than that in which our army marched from the Rapidan to the James. From Georgia, too, we have similar accounts of difficulties met only to be surmounted. Heaven bless our gallant soldiers everywhere! A nation's hopes and prayers are with them. May they know the soldier's dearest delight—victory!

1

Λἁβωρον, also λἁβουρον; derived, not from labor, nor from λἁφυρον, i.e., præda, nor from λαβεἱν, but probably from a barbarian root, otherwise unknown, and introduced into the Roman terminology, even before Constantine, by the Celtic or Germanic recruits. Comp. Du Cange, Glossar., and Suicer, Thesaur. s.h.v. The labarum, as described by Eusebius, who saw it himself (Vita Const. i. 30), consisted of a long spear overlaid with gold, and a cross piece of wood, from which hung a square flag of purple cloth, embroidered and covered with precious stones. On the top of the shaft was a crown composed of gold and precious stones, and containing the monogram of Christ (see next note), and just under this crown was a likeness of the emperor and his sons in gold. The emperor told Eusebius (I. ii. c. 7) some incredible things about this labarum, e.g. that none of its bearers was ever hurt by the darts of the enemy.

2

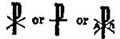

X and P, the first two letters of the name of Christ, so written upon one another as to make the form of the cross:

3

Cicero says, pro Raberio, c. 5: 'Nomen ipsum crucis absit non modo a corpore civium Romanorum, sed etiam a cogitatione, oculis, auribus.' With other ancient heathens, however, the Egyptians, the Buddhists, and even the aborigines of Mexico, the cross seems to have been in use as a religious symbol. Socrates relates (H.E. v. 17) that at the destruction of the temple of Serapis, among the hieroglyphic inscriptions, forms of crosses were found which pagans and Christians alike referred to their respective religions. Some of the heathen converts, conversant with hieroglyphic characters, interpreted the form of the cross to mean the Life to come. According to Prescott (Conquest of Mexico, iii. 338-340) the Spaniards found the cross among the objects of worship in the idol temples of Anahnac.

4

Late Southern newspapers speak of the obstinacy of the garrison at Fort Pillow, and assert that Forrest would have stopped the massacre at any time after the capture, if our soldiers had manifested any disposition to yield.

5

The writer's father saw these skulls hanging in the cars on a railway in Georgia, after first Bull Run, and saw them handed through the cars amid the jeers of passengers.