полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol. 6, No 2, August, 1864

The chief duties of officers belonging to the corps of engineers, when connected with an army acting in the field, are the supervision of routes of communication, the laying of bridges, the selection of positions for fortifications, and the indication of the proper character of works to be constructed. Should a siege occur, a new and very important class of duties devolves on them, relating to the trenches, saps, batteries, etc.

Not only is there in Virginia a lack of good roads, but the numerous streams have few or no bridges. In many cases where bridges have existed, one or the other of the contending armies has destroyed them to impede the march of its opponents. Streams which have an average depth of three or four feet are, however, generally without bridges, except where crossed by some turnpike, the common country roads mostly leading to fords. The famous Bull Run is an example. There were but two or three bridges over this stream in the space of country penetrated by the roads generally pursued by our army in advancing or retreating, and these have been several times destroyed and rebuilt. The stream varies from two to six feet in depth—the fords being at places of favorable depth, and where the bottom is gravelly and the banks sloping. Often such streams as this, and indeed smaller ones, become immensely swelled in volume by storms, so that a comparatively insignificant rivulet might greatly delay the march of an army, if means for quickly crossing should not be provided. The general depth of a ford which a large force, with its appurtenances, can safely cross, is about three feet, and even then the bottom should be good and the current gentle. With a greater depth of water, the men are likely to wet their cartridge boxes, or be swept off their feet. There is a small stream about three miles from Alexandria, crossing the Little River turnpike, which has never been bridged, and which was once so suddenly swollen by rain that all the artillery and wagons of a corps were obliged to wait about twelve hours for its subsidence. The mules of some wagons driven into it were swept away. Fords, unless of the best bottom, are rendered impassable after a small portion of the wagons and artillery of an army have crossed them—the gravel being cut through into the underlying clay, and the banks converted into sloughs by the dripping of water from the animals and wheels.

A very amusing scene was presented at the crossing of Hazel River (a branch of the Rappahannock) last fall, when the Army of the Potomac first marched to Culpepper. The stream was at least three feet deep, and at various places four—the current very rapid—the bottom filled with large stones, and the banks steep, except where a narrow road had been cut for the wagons. The men adopted various expedients for crossing. Some went in boldly all accoutred; some took off shoes and stockings, and carefully rolled up their trousers; others (and they were the wisest) divested themselves of all their lower clothing. The long column struggled as best it could through the water, and occasionally, amid vociferous shouts, those who had been careful to roll up their trousers would step into a hole up to the middle; others, who had taken still more precautions, would stumble over a stone and pitch headlong into the roaring waters, dropping their guns, and splashing vainly about with their heavy knapsacks, in the endeavor to regain a footing, until some of their comrades righted them; and others, after getting over safely, would slip back from the sandy bank, and take an involuntary immersion. Some clung to the rear of the wagons, but in the middle of the stream the mules would become fractious, or the wagon would get jammed against a stone, and the unfortunate passengers were compelled to drop off and wade ashore, greeted by roars of derisive laughter. On such occasions soldiers give full play to their humor. They accept the hardships with good nature, and make the best of any ridiculous incident that may happen. At the time referred to, many conscripts had just joined the ranks, and cries resounded everywhere among the old soldiers: 'Hello, conscripts, how do you like this?' 'What d'ye think of sogering now?' 'This is nothing. You'll have to go in up to yer neck next time.'

Generally, when the exigencies of the march will permit, bridges are made over such streams, either by the engineers of the army, or detachments from the various corps which are passing upon the roads. They are simple 'corduroy bridges,' and can be laid very expeditiously. Two or three piers of stones and logs are placed in the stream, string pieces are stretched upon them, and cross pieces of small round logs laid down for the flooring. The most extensive bridges of this kind used by the Army of the Potomac were those over the Chickahominy in the Peninsular campaign. 'Sumner's bridge,' by which reinforcements crossed at the battle of Fair Oaks, was laid in this manner. Of course such bridges are liable to be carried away and to be easily destroyed. Some of the bridges over the Chickahominy were laid much more thoroughly. 'Cribs' of logs were piled in cob-house fashion, pinned together, and sunk vertically in the stream. Then string pieces and the flooring were laid, the whole covered with brush and dirt. Men worked at these bridges up to the waist in water for many days in succession.

Military art has devised many expedients for bridging streams, and use is made of any facilities that may be at hand for constructing the means of passage; but the only organized bridge trains which move with the army are those which carry the pontoons. Of these there are various kinds, made of wood, of corrugated iron, and of india rubber stretched over frames. But the wooden pontoon boats are most in use. They can be placed in a river and the flooring laid upon them with great rapidity. Several very fine bridges have been thus constructed—among them may be mentioned the one at the mouth of the Chickahominy, across which General McClellan's army marched in retreating from Harrison's Landing. It was about a mile long, and was constructed in a few hours.

To cross a river under the fire of an enemy is one of the most difficult operations in warfare. Yet it has been frequently accomplished by our armies. The crossing of the Rappahannock by General Burnside's army, previous to the great battle of Fredericksburg, in December, 1862, is one of the most remarkable instances of the kind during the war. The rebel rifle pits lined the southern bank, and the fire from them prevented our engineers from approaching—the river being only about seventy-five yards wide. For a long time our artillery failed to drive the rebels away. About noon of the day on which the crossing was made, General Burnside ordered a concentration of fire on Fredericksburg, in the houses of which place the rebels had concealed their forces. A hundred guns, hurling shot and shell into every building and street of the city, soon riddled it; but the obstinate foes hid themselves in the cellars till the storm was over, and then emerged defiantly. They were only dislodged by sending over a battalion in boats to attack them in flank, when they retreated, and the bridges were laid.

It is impossible to explain in articles of this character the mysteries of intrenchment and fortification, so that they will be comprehensible. A few notes, however, on some of the principal terms constantly employed, may be found useful and interesting.

Rifle pits—as the term is now generally used—are small embankments, made by throwing up dirt from an excavation inside. They can be erected quickly, for it will be seen that those behind them have the advantage, not only of the height of the embankment, but also of the depth of the ditch. Thus an excavation of two feet would give a protection of four feet. This is the ordinary rifle pit, but when time permits it receives many improvements.

Breastworks are any erections of logs, dirt, etc., raised breast high, to shelter the men behind them.

An abatis consists of obstructions placed in front of a work to form obstacles to a storming party. The most convenient method of forming it is to cut down trees and allow them to lie helterskelter. When there is time, the trees are laid with the butts toward the work, and the branches outward—the small limbs being removed, and the ends of the remainder sharpened.

A redan is a letter V, with the point toward the enemy, and is used generally to cover the heads of bridges, etc.

A lunette is the redan with flanking wings.

A redoubt is an enclosed parallelogram.

These works are very imperfect, because they have exposed points. The angles are not protected by the fire from the sides. To remedy this difficulty, the next most usual work is the star fort, made in the form of a regular or irregular star. It will be perceived that the fire from the sides covers the angles.

The next and still more improved form of work is the bastioned fort, which consists of projecting bastions at the corners, the fire from which enfilades the ditches.

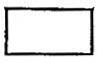

The following is a diagram of a vertical section of the parapet and ditch used in all fully constructed field works:

A B is the slope of the banquette.

B C head of the banquette, or place where the men stand to deliver their fire.

C D the interior slope of the parapet.

D E superior slope of the same.

F G the berme, or place left to prevent the parapet from washing down into the ditch.

G H the scarp or interior wall of the ditch.

H I the bottom of the ditch.

I K the counterscarp.

L M N the glacis, which, except the abatis near the ditch, is left free and open, so as to expose the assailants to the fire from the parapet.

The proportions and angles of all the lines given are fixed according to mathematical rules.

The operations of a siege present many incidents of great interest; but we can do nothing more in this article than illustrate the methods in which the approaches are made to the works the capture of which is designed. When reconnoissances have established the conclusion that the works of an enemy cannot be carried by assault, the lines of the investing army are advanced as near to them as is compatible with safety; advantage is then taken of the opportunities afforded by the ground to cover working parties, which are thrown forward to the place fixed for the first parallel; sometimes these parties can commence their work only at night. The parallel is only a deep trench with the dirt thrown toward the enemy; and after the excavation has progressed, the trench is occupied by parties of troops to resist any sorties of the enemy, and to prevent attempts against the batteries established behind the parallel.

The first parallel being completed, zigzag excavations are made toward the front to cover the passage of men who proceed to dig the second parallel. Meanwhile the batteries have commenced to play, and riflemen have been advanced in trenches at convenient places, whose fire annoys the gunners of the enemy. The second parallel being made, the batteries are moved up to it, and the third parallel is proceeded with in a manner similar to that used for the second.

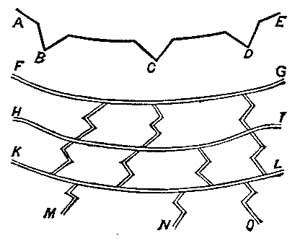

We give below a rough diagram of these operations:

A B C D E is the work of the enemy to be besieged. The working parties advance by the zigzag paths M N and O to the position chosen for the first parallel, K L. At the proper time they proceed by the zigzag paths to the second parallel, H I, and then to the third, F G. When this is reached, the enemy's work can generally be carried by storm, unless already evacuated, for ceteris paribus the advantages generally lie with the besieging party. The zigzags are called boyaux, and they are dug in the form represented, so that the bank of earth thrown up may be always in front of them. Were they in straight lines this could not be.

The above refers exclusively to the siege of a field work. The principles for besieging a walled fort or a fortified town are the same, but the operations are much more complicated.]

LITERARY NOTICES

Popular Edition. Results of Emancipation. By Augustin Cochin, Ex-Maire and Municipal Councillor of Paris. Work crowned by the Institute of France (Académie Française). Translated by Mary L. Booth, Translator of Count de Gasparin's work on America, etc. Fourth thousand. Boston: Walker, Wise & Co., 245 Washington street. 1864.

A remarkable book, indicative of a new era in the discussion of social, religious, political, and economical questions. Prejudice, misstatement, and fanaticism are apparently so opposed to the clear, candid mind of the author, that he has needed no effort to avoid them, and in their stead give us simple truth, broad views of men and things, and the highest conceptions of duty and charity, together with the nicest consideration of the rights and material interests, even the local prejudices and misconceptions, of our fellow mortals. He shows clearly that a moral wrong can never long tend to material advantage, and that the laws of society cannot be made ultimately to triumph over the laws of nature; neither, in general, can a wrong be righted without some suffering by way of expiation.

Although filled with statistical details, the work cannot fail to be intensely interesting to the general reader. Lofty, hopeful, rational, and yet progressive in its tone, it is calculated to do great good, not only through the useful information and instructive generalizations it makes known, but also as a model of right feeling, and consequent good breeding, in its peculiar sphere.

The chapters upon the sugar question are wonderfully lucid and convincing. Their bearing upon mooted points of political economy recommend them to the study of all interested in that intricate subject. The distressing relations necessarily existing between slavery and religious instruction are also plainly set forth, and the general conclusion of the book (that 'emancipation' is not only possible, but most expedient, and that, with certain care upon the part of the Government and of slave owners, an immediate and simultaneous liberation is likely to breed fewer disturbances and less evil than gradual disenthralment) seems to be rapidly gaining ground in the convictions of our own countrymen. The conscience, and prophetic dreams of priests, women, and poets, have long given assurance of such results, but the world, of course, required definite experience and practical essays before instituting any extensive course of action in that direction.

'A council held in the city of London in 1102, under the presidency of St. Anselm, interdicted trade in slaves. This was eight hundred years before the same object was debated in the same city before Parliament. In 1780, Thomas Clarkson proposed to abolish the slave trade. In 1787, Wilberforce renewed the proposition. Seven times presented from 1793 to 1799, the bill seven times failed. Successively laid over, it triumphed at length in 1806 and 1807. All the Christian nations followed this memorable example. At the Congress of Vienna, all the Powers pledged themselves to unite their efforts to obtain the entire and final abolition of a traffic so odious and so loudly reproved by the laws of religion and nature. The slave trade was abolished in 1808 by the American United States; in 1811, by Denmark, Portugal, and Chili; in 1813, by Sweden; in 1814 and 1815, by Holland; in 1815, by France; in 1822, by Spain. In this same year, 1822, Wilberforce attacked slavery after the slave trade, and won over public opinion by appeals and repeated meetings, while his friend Mr. Buxton proposed emancipation in Parliament. The Emancipation Bill was presented in 1833. On the 1st of August, 1834, slavery ceased to sully the soil of the English colonies. In 1846, Sweden, in 1847, Denmark, Uruguay, Wallachia, and Tunis, obeyed the same impulse, which France followed in 1848, Portugal in 1856, and which Holland promised to imitate in 1860. An earnest movement agitated Brazil.'

In Poland, the serfdom of the peasants was never sanctioned by law, but existed in later times by reason of exception and abuse. Stanislas Leszczynski, King of Poland, in 1720 raised his voice in favor of the peasant population; the same principles were in 1768 defended, sword in hand, by the Confederation of Bar, discussed in the diets of 1776, 1780, 1788, and finally adopted by the famous Constituent Assembly of 1791. Thadeus Kosciuszko (May 7th, 1794), then Dictator of Poland, issued a document giving entire personal liberty to all serfs; and on the 22d of January, 1863, the members of the 'National Polish Government' decreed that the peasants were not only free, but were entitled to a certain portion of land, of which they should be the sole proprietors. In 1861, Russia emancipated all serfs within her borders. In the United States, the stern 'logic of events' seems to be rapidly bringing about similar results, although indeed 'slavery' and 'serfdom' should never be mentioned together, being so essentially different; the one the possession of the man, the other merely the ownership of his labor or of a portion of its results.

We cannot better conclude than by giving the following extract from the Introduction of M. Cochin, who, by the way, is a man of good family and ample fortune, an eminent publicist, and a Catholic of the school of Lacordaire, Montalembert, Monseigneur d'Orleans, and the Prince de Broglie:

'It was once exclaimed, Perish the colonies, rather than a principle! The principle has not perished, the colonies have not perished.

'It is not correct that interests should yield to principles; between legitimate interests and true principles, harmony is infallible; this is truth. Those who look only to interests are sooner or later deceived in their calculations; those who, exclusively occupied with principles, are generous without being practical, cease to be generous, for they lead the cause which they serve to certain destruction. It is the will of God that realities should mingle with ideas, and that material obstacles should compel the purchase of progress by toil.'

The publishers tell us that, a large demand for this work having arisen, they have issued this 'popular edition,' wherein the figures in the original are given as nearly as possible in the American currencies, measures, etc.

Stumbling Blocks. By Gail Hamilton, Author of 'Country Living and Country Thinking,' 'Gala Days,' etc. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, For sale by D. Appleton & Co., New York.

Gail Hamilton's religious position gives her vast advantages. She is thoroughly orthodox, Calvinistic, and Congregational, and being neither Unitarian nor Catholic, will not be regarded as one of the 'Suspect' by the great community of the so-called evangelical Christians. But she is a bold, independent thinker, and spurns the trammels of bigotry and prescription. No party spirit blinds her clear vision, no sectarian prejudice vitiates her statements of the creeds of others, or induces her to veil the faults and follies of those worshipping in the same church with herself. Ministers are by no means immaculate saints in her eyes. Seating herself in the pews, she preaches better sermons to them than they are in the habit of giving to their people; taking possession of their pulpits, she shows them what might and ought to be done from that throne of power. Petty vanities, subjective experiences recorded in morbid journals, religious frames of mind frequently dwelt upon until the tortured self-watcher is driven into insanity, fall under her scathing rebuke.

This volume deals chiefly with the shortcomings of the orthodox religious world. Its faults of temper, its repulsive manners, its custom of making home unlovely, its distaste of innocent amusement, its habits of censure, its self-sufficiency and pharisaical character, are touched with a caustic but healing power. Only the hand of a friend could have done this thing. No point of doctrine is questioned, no principle of faith invaded, no charity wounded. She probes in love—her object is cure. This book is fresh and vigorous, worth thousands of lifeless sermons and unprofitable religious journals. No prejudice or falsehood is spared, though it may have taken refuge in the very sanctuary. Her every shaft is well directed, every arrow powerfully sent, every shot strikes the bull's eye in its centre. Her words are hailstones rattling fell and fast, but melt into and soften the heart on which they fall. Delusions disappear, cant and want of courtesy become odious, shams grow shameful, while all lovely things bloom lovelier in the light of truth emanating from this large brain, and poured through this living heart. We bask in its sunshine, growing strong and happy as we read. Christian fervor and charity, love for Redeemer and redeemed, for saint and sinner, cheer us through all these well-deserved denunciations. Her style is clear and rapid, her matter of daily and urgent import, her characterizations of classes and types of men worthy of La Bruyère himself, her satire melts into humor, her humor into pathos. She has been attacked by some of the religious papers, and has herein taken a true Christian and magnanimous revenge. O Gail! the clergy should open wide their hearts to take you in, their gifted child, the iconoclast within the temple, the faithful disciple of Christ, the lover of purity and truth!

We quote the following brave words from this remarkable book:

'We sometimes see religious newspapers charging each other with acts which should exclude the perpetrators from the fraternity of honest men; for, through the medium of religious newspapers, one church, or one fraction of a church, or one ecclesiastical body, or one member of it, accuses another of an act, or a course of action, which, in sober truth, amounts to nothing more or less than obvious, persistent deception, dishonesty and trickery.... Can such be correct transcripts of facts? Is it true that a church, or any body corporate, whose very existence as such is professedly to cultivate and disseminate the principles of sound morality and true religion, does fall so far short of the faith delivered to the saints—does so far forget its origin, and pervert its aims, as to violate common law and common honesty, and persist in its violation, deliberately, against repeated remonstrances, by sheer force? Yet we see no convulsion in the community. Nothing intimates that a great grief is fallen upon Israel. Everybody eats, drinks, and sleeps as usual. The pulpits still stand, and the law and the gospel are appealed to from that vantage ground. The sacramental cup is still raised to devout lips. The gray heads of the culprits still go in and out among the people with no diminishing of honor—no odium is attached to their persons; no stigmas to their names. What a state of things does this argue! A whole church plunges into darkness, and the

'Majestic heaven

Shines not the less for that one vanished star.'

'Can we wonder that the world will not let itself be converted? To what should it be converted, if it were willing? Would it be an advance for a community that sends its thieves to prison when it catches them to merge itself in a community that is content to print a few columns of exposé on the subject? If the stream where you wish to drink is muddy, you will scarcely find clear waters by descending. You want to go up, not down; up on the high lands where threads of crystal cleave the gray old rocks, and gather purity from earth's deep bosom and the sky's clear blue.

'If it is not so, if the acts only appear dishonest because we are looking at one side, why do we not say so, or why do we say anything about it? Every man is to be held innocent till he is proved guilty. If there is any standpoint from which we can view our opponent's position and find it not dishonest, we ought to mention it. We have no right to look at him from a standpoint, and hold him up to view as a criminal, and ignore another, from which he may be seen as simply mistaken, or deceived, or blameless. Still less have we a right to take innocent facts and construct upon them a guilty hypothesis to suit our foregone conclusion. A right to do it? It is sin. It is more than murder. It may rob a man of what is more precious to him than his life. It attempts to take away from a man what, taken, would leave him stripped of his manhood, and a man's manhood is worth more to him and his friends than his bone and muscle.'