Полная версия

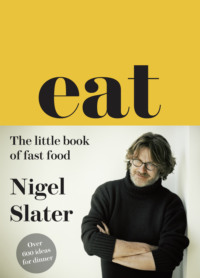

The Kitchen Diaries II

potatoes: 400g

a large onion

olive oil: 2 tablespoons

gurnard or similar white fish: 4 large fillets (about 450g), skinned

basil leaves: 15g

double cream: 250ml

butter

Peel the potatoes, slice them roughly the thickness of a pound coin, bring them to the boil in lightly salted water, then leave to cook at a gentle boil for five or six minutes. Drain and set aside. Set the oven at 200°C/Gas 6.

Peel and finely slice the onion, then let it cook in the oil in a shallow oven-proof pan for five to ten minutes, till it has softened but not coloured. Switch off the heat. Season the fish fillets with salt and black pepper, then place them on top of the onion. Shred the basil leaves and stir them into the cream with a light seasoning of salt. Pour the cream over the fish, then lay the sliced potatoes on top, neatly and slightly overlapping. Season and dot the surface with butter.

Bake for thirty to forty minutes, till the potatoes have lightly browned.

Enough for 2

…and the beauty of a winter salad

The crisp, winter leaves – trevise, radicchio, in fact all the chicories – have a beauty not present in the lush green leaves of summer. Their wayward curls, like tendrils of squid, the flashes of magenta, rose and blood-red on white as if they have been painted by hand, all lead us to want to use these leaves whole rather than chopped or torn. The shape of the leaves is as much a part of their attraction as their flavour, their dazzling colours only becoming clear and bright in cold weather. Just as importantly, there is a bitterness to the winter leaves that makes them a perfect match for the sweetness of walnuts, mild cheeses (the Gloucesters, the Beaufort family) and bacon.

I find something endearing about the fact that the sweeter leaves are those nearest the heart. The most bitter – and the ones I like the most – are the ones that grow on the outside. The more light they receive, the deeper their pungency. The intensely coloured, rabbit-eared raddichios are especially handsome on a white plate. The one that melts people’s hearts is the Castelfranco variety, with its cream, rough-edged leaves speckled with maroon and pink. It’s a rare find, but a showstopper on the plate, perhaps with slices of Russet apple.

I grow several varieties of winter lettuce in pots in the cold frame. They seem to sit there sulking, then take me by surprise by appearing as fist-sized whorls of beautiful, rose-tinted leaves with freckles of deepest burgundy. The cold spurs on their growth, just as it does the snowdrops and narcissi in the garden. There is the curiously waxy claytonia, sometimes known as winter purslane, landcress with its iron-rich flavour, buttery lamb’s lettuce, and all of them can be grown outdoors, even when there is frost on the ground. Sow in August and harvest all winter.

The dressings for winter salads are something I tend to introduce a touch of sweetness to, in the form of walnut oil or balsamic vinegar, as a knee-jerk contrast. Occasionally it is worth flying more dangerously and adding other pungent flavours – capers, gherkins, mustard and salty, palate-cleansing cheeses – to the leaves too. The shock of the bitter, the sour and the pungent, together with the crunch of the leaves, makes for refreshing, sense-awakening eating.

Winter leaves with gherkins and mustard

white chicory, frisée or other crisp, bitter winter leaves: 4 double handfuls

watercress: a large bunch

For the dressing:

a large egg yolk

Parmesan: 50g, finely grated

Dijon mustard: a teaspoon

white wine vinegar: a teaspoon

mild olive oil: about 100ml

gherkins: 2 tablespoons, finely chopped

capers: a teaspoon, rinsed

To make the dressing, put the egg yolk into a food processor, add the grated Parmesan, mustard and wine vinegar and switch the machine on. Pour in the oil rather slowly, as if you were making mayonnaise. Stop adding it when you have a smooth sauce that is thin enough to fall slowly from a spoon. Stir in the chopped gherkins and rinsed capers. Add no salt.

Rinse and trim the salad leaves, removing any tough stalks from the watercress. Spin or shake dry. Gently toss the leaves in the dressing and pile on to plates.

Enough for 4

JANUARY 28

Using up the marzipan

There is some marzipan left over from Christmas. It’s the uncoloured sort, a soft shade of buttermilk, which I brought back from a trip to Oslo at the beginning of Advent. Made from ground almonds, sugar and egg moulded into a stiff paste, marzipan is a like-it or loathe-it thing. I like it best coated with bitter chocolate, partly because the coating keeps the almond paste moist but also because of the contrast of crisp chocolate and soft, sweet marzipan. I must admit to a curious soft spot for those slightly stale-tasting marzipan fruits and vegetables from Palermo (carrots, apples, peaches and even cauliflowers) that you can buy at Christmas.

Although marzipan originated in Persia, where it is often flavoured with orange flower water, almost every almond-producing country has its own version. The almond paste is linked to any manner of ceremonies, from the wedding feasts of the Aegean to All Souls’ Day – il giorno dei morti – in Palermo. But mostly, marzipan, massepain (French), mazpon (India) or mazapan (Philippines), is just as much a part of Christmas as mince pies.

I bought mine in Norway only because I had browsed a little too long in a cake-decorating shop and felt guilty not making a purchase, but it is essential to read the packet. A few versions sold abroad are made with peanuts or cashews instead of almonds. I have yet to taste persipan, the version made from peach kernels. It sounds fun.

The marzipan from Lübeck in Germany is reputed to be the finest, partly because of the high percentage of almonds to sugar. A general rule is that the more gaudy the presentation, the lower the quality is likely to be. The cheaper brands tend to contain sugar syrup and a hefty dose of colouring and flavouring.

I sometimes make my own, combining finely ground almonds with a mixture of icing and caster sugar, egg yolk and a little grated orange zest. It’s a pleasing sugar and spice job, something for a frosty or even snowy afternoon.

Whilst in Norway, I came across some shallow, moist almond cakes studded with dark berries that had a little almond paste in them. Once home, I set about tinkering with my classic almond sponge mixture and some frozen blackcurrants and blueberries, but it was only once I added some crumblings of marzipan that my cakes approached those I had eaten rather too many of in Oslo. Recipes like this are trial and error, but I eventually got it to where I wanted it to be: the cake crumb moist and slightly squidgy, the fruit seeping its sharp juice, and here and there sweet nuggets of almond paste.

Almond, marzipan and berry cakes

My version of the sweet, almond-scented cakes I ate in one of Oslo’s most popular new-wave bakeries.

You will need six shallow round cake tins about 10cm in diameter or rectangular baking tins, about 8cm x 10cm.

butter: 180g

caster sugar: 180g

eggs: 2, lightly beaten

plain flour: 80g

ground almonds: 150g

marzipan: 100g

berries (assorted blueberries and currants), fresh or frozen: 200g

icing sugar

Line the cake tins with baking parchment. Set the oven at 180°C/Gas 4.

Using an electric beater, cream the butter and sugar together till pale and fluffy. Gradually beat in the eggs, then slowly introduce the flour and ground almonds. Once they are incorporated, stop the machine immediately.

Break the marzipan into small pieces about 1–2cm in diameter. Stir these into the mixture. Divide it between the baking tins, then scatter the fruit over the top of each. Bake for forty minutes, till lightly firm to the touch. Remove from the oven, dust with icing sugar and leave to cool before serving.

Makes 6

JANUARY 30

And using up the marmalade

The opened jars of sweet preserves in the fridge seem to be multiplying. I don’t mind, I think of them as treasure. Right now there are blackcurrant, damson and mulberry jams; a pot of lemon curd and another of damson jelly; French apricot jam, some Lebanese rose petal jelly and three different marmalades. Three. One of these jars of orange preserve I proudly made myself last February from organic, green-tinged Seville oranges, the other two were gifts, finer than my own and with fewer strips of peel. I have the urge to use all three up, scraping out every last amber mouthful with a teaspoon, getting my knuckles sticky in the process, and use the sweet-sharp jelly in an ice cream. The recipe is an experiment, a marriage of shards of bitter chocolate and orange preserve. I end up with beautiful, custard-coloured, soft-scoop ice cream of which I am almost absurdly proud.

Ice cream, when it is home made, has a habit of setting like a brick. Many is the time I have sat, well beyond midnight, chipping off little shards and flakes with a teaspoon. The classical way round this is to add some glucose syrup to the mix, resulting in a soft-scoop texture. Adding marmalade turns out to work much the same magic, only in a way that seems more wholesome. The ice is the most silkily textured I have ever made. The flavours are stunning. If only cooking was always like this.

Marmalade chocolate chip ice cream

single or whipping cream: 500ml

egg yolks: 4

golden caster sugar: 2 tablespoons

marmalade: 400g

dark chocolate: 100g, roughly chopped

Bring the cream to the boil. Beat the egg yolks and sugar in a heatproof bowl till thick, then pour in the hot cream and stir. Rinse the saucepan and return the custard to it, stirring the mixture over a low heat till it starts to thicken slightly. It won’t become really thick. Cool the custard quickly – I do this by plunging the pan into a shallow sink of cold water – stirring constantly, then chill thoroughly.

Stir the marmalade into the chilled custard. Now you can either make the ice cream by hand or use an ice-cream machine. If making it in a machine, pour in the custard and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When the ice cream is almost thick enough to transfer to the freezer, fold in the chopped chocolate, churning briefly to mix. Scoop into a plastic, lidded box and freeze till you are ready.

If you are making it by hand, pour the custard and the chopped chocolate into a freezer box and place it in the freezer, removing it and giving it a quick beat with a whisk every hour until it has set.

Enough for 6

February

FEBRUARY 4

It wasn’t, on reflection, the wisest of days to make marmalade. I had pruned the roses, the temperature was a degree or two below freezing, and the skin around my thumbnail had cracked open in the cold. Each drop of bitter orange juice, each squirt of lemon zest sent shots of stinging pain through my thumb. But the Seville orange season is over in the blink of an eye and sometimes you just have to shut up and get on with things.

Marmalade making is about as pleasurable as cooking can get. It isn’t something for those whose only reason for cooking is the finished product. If the process of peeling oranges, painstakingly cutting their skin into fine strands and constantly checking their progress on the stove is a chore, then don’t do it. There is enough exceptionally good cottage-industry marmalade out there. Go and buy it. Making marmalade is a kitchen job to wallow in, to breathe in every bittersweet spray of zest, enjoy the prickle of the fruit’s oils on your skin and fill the house with the scent of orange nectar (or, of course, screech with pain as the bitter juice gets into your wounds).

Each stage, and there are several, carries with it waves of extraordinary pleasure. I say extraordinary because it is not every day you get the chance to fill the house with a lingering smell that starts as bright and clean as orange blossom on a cold winter breeze and ends, a day later, with a house that smells as welcoming as warm honey. There is something heart-warmingly generous about marmalade makers. I can’t tell you how many jars I have been given over the years. In my experience they like nothing more than passing their golden pots of happiness on to others.

There must be hundreds of recipes, but it is the method that changes rather than the ratio of ingredients. Some cooks swear by boiling the oranges whole, then chopping them; others cut the fruit into whole slices, others still include the pith in the jam itself, while some nitpickingly remove it. I have met cooks who chuck their boiled peel in the food processor, some who add a lemon or two, and those who introduce a couple of sweet oranges. It probably goes without saying that there is someone out there making it in minutes in the microwave (and surely missing the whole damn point).

The method you choose will depend on how you like your marmalade. Don’t probe a marmalade fan on the subject of texture unless you are actually in need of a Mogadon. Some of us like ours soft and syrupy, others prefer a jam that will stand to attention on the spoon. I like my peel in thin, hair-like strips, while friends insist on juicy chunks. Then there are those who leave the fruit in whole slices or cut it into fat nuggets. In my experience the latter produces the marmalade most likely to fall off your toast while you are engrossed in Nancy Banks-Smith or the Today programme. Lastly, there’s the lot who insist on sieving their pith out altogether. And the lovely thing is that each and every one of us is right.

I like my marmalade to shine in the morning sun. A bright, jewel-like mixture with thin strands of peel, quivering, but not so loosely set that it drips down the sleeves of my dressing gown. The point of this golden jam is its bittersweet quality. It’s a wake-up call in a jar. That is why we eat it first thing in the morning. The bitter oranges you need are available for a short season in January and February.

I know I am stepping into deep water giving a marmalade recipe, which is partly why it has taken me twenty years to get round to offering you one, but marmalade recipes are very personal things and we marmalade makers are a proud bunch (which is possibly another reason why we give so much of it away). But here it is, a little pot or two of bright, shining happiness, full of bittersweet flavour and stinging thumbs.

Seville orange marmalade

I made two batches this year. One with organic fruit, the other not. The flavour of the organic one shone most brilliantly and took less time to reach setting point.

Makes enough to fill about 5 or 6 jam jars.

Seville oranges: 1.3kg

lemons: 2

golden granulated sugar: 2.6kg

Using a small, particularly sharp kitchen knife, score four lines down each fruit from top to bottom, as if you were cutting it into quarters. Let the knife cut through the peel without piercing the fruit. Remove the peel, cut each quarter of peel into fine shreds (or thicker slices if you like a chunkier texture) and put into a large bowl. Squeeze in the juice from the peeled oranges and lemons with your hands, chop the pulp and add it, removing the pips. Add 2.5 litres of cold water. Tie the pips in a muslin bag and push into the peel and juice. Set aside in a cold place and leave overnight.

The next day, tip the mixture into a large stainless steel or enamelled pan (or a preserving pan for those lucky enough to have one) and push the muslin bag down under the juice. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat so that the liquid continues to simmer merrily. It is ready when the peel is totally soft and translucent. This can take anything from forty minutes to a good hour and a half, depending purely on how thick you have cut your peel (this time, mine took forty-five minutes).

Once the fruit is ready, lift out the muslin bag and leave it in a bowl until it is cool enough to handle. Add the sugar to the peel and juice and turn up the heat, bringing the marmalade to a rolling boil. Squeeze every last bit of juice from the reserved muslin bag into the pan. Skim off any froth that rises to the surface (if you don’t, your preserve will be cloudy). Leave at a fast boil for fifteen minutes. Remove a tablespoon of the preserve, put it on a plate and pop it into the fridge for a few minutes. If a thick skin forms on the surface of the refrigerated marmalade, then it is ready and you can switch the heat off. If the tester is still liquid, then let the marmalade boil for longer, testing every ten to fifteen minutes. Some mixtures can take up to fifty minutes to reach setting consistency. Ladle into sterilised pots and seal immediately.

FEBRUARY 7

Fish, some new thoughts

I like February, with its grey-white skies and snowdrops. In the kitchen it is the time for long-cooked dishes of earth-coloured pulses, meat on its bones and home-made cakes. A month of beans, bones and baking. But it is also the month I go on holiday. Not towards warmth and bright sunshine, but places cold and icy, with crisp air that reminds you that you are alive.

Little feels more right than eating fish within a few steps of the sea. A lunch in Oslo, now a favourite place to escape, of fish soup flavoured with basil, eaten within sight of seventy white masts in a harbour with water like a black mirror, feels about as right as any meal I have ever eaten. Even more so as I saw the fish arrive barely twenty minutes before.

I have eaten nothing but fish for several days now – give or take the odd marzipan-filled, cardamom-scented maple syrup bun. The most curious was my lunch yesterday, of Arctic char served with chestnuts, bacon and apple purée. You feel it shouldn’t work, the flavours being more suited to pork or perhaps reindeer, but it does. A dish ordered partly out of novelty, partly out of disbelief. It’s clever, because the apples are cut into the tiniest imaginable dice and mixed with celery before being fried and served with the fish. It is a bit of a nancy presentation, but it leaves me inspired enough to have a go at home.

I have always loved the colour grey. Peaceful, elegant, understated; the colour of stone, steel and soft, nurturing rain. The view from the window across the harbour has every shade, from driftwood to charcoal: the lagoon, the restaurant’s weathered cedar cladding, the moored boats, the trees on the opposite shore, all in delicate shades of calming grey.

The monotones through the window aren’t altered by my plate of scallops, two if we are being precise, shallow fried, with a julienne of apple on top. Creamy, buttery cauliflower purée, black pepper and tiny bits of fried cauliflower complete the dish. It’s a study in cream and white on a white plate, eaten under a stainless sky. A scene of such subtlety it makes everything else look gaudy and crass. There is risotto too, a blissful combination of smoked cod and spinach. As soon as I am off the plane, back in my own kitchen, I will ape that restaurant’s sublime risotto.

A risotto of smoked cod and spinach

And I did …

milk: 450ml

smoked cod or haddock: 400g

bay leaves: 2

black peppercorns: 6

hot stock: 450ml

a small onion

butter: 50g

Arborio or other risotto rice: 250g

a glass of white wine

spinach leaves: 2 handfuls

Pour the milk into a saucepan large enough to take the fish. Place the fish in the milk, add the bay leaves and peppercorns, then bring to the boil. As soon as the milk shows signs of foaming, lower the heat and simmer for ten minutes. Turn off the heat and leave the milk to infuse with the fish and aromatics. Heat the stock in a saucepan; it should simmer lightly whilst you are making the risotto.

Peel and finely chop the onion, then fry gently in the butter in a broad, heavy-bottomed pan. When the onion is soft and translucent, and before it colours, add the rice and briefly stir it through the butter to coat the grains. Pour in the wine, let it evaporate, then add the stock a ladleful at a time, allowing each one to be soaked up by the rice before adding the next, stirring continually and keeping the heat moderate to low. Once the stock has been used up, change to the milk, strained of its peppercorns. By the time almost all the milk has been absorbed, the grains should be soft and plump yet with a firm bite to them. Season carefully. The total cooking time will probably be about twenty minutes, maybe a few minutes longer.

Wash the spinach leaves, tear them into small pieces, then stir them into the rice. Break the fish into large, juicy flakes and add them to the rice, folding them in but keeping the flakes as whole as possible. Check the seasoning and serve.

Enough for 2 generous servings

FEBRUARY 9

A little brown stew for a little brown day

A certain calm comes over the kitchen when there is any sort of grain simmering on the stove. The steam from brown rice, spelt or pot barley brings with it a quiet benevolence that I am grateful for on a grey-brown day like today. With a house in turmoil (I remain holed up in my tiny study while the plasterers plaster, painters paint and welders weld) the homely smell of boiled rice is somehow reassuring.

All the grains appeal to me but I am becoming partial to the quiet pleasures of pearled spelt (think pearl barley but made from wheat). The pale-brown wheat grain makes a pleasing change from Arborio rice in a risotto and adds a chewy note to a herb salad, but is something to consider for bulking up a casserole, too. The small, oval grains plump up like Sugar Puffs with the aromatic cooking liquor from a stew, taking on a velvety texture whilst making the dish both more substantial and more economical.

The mushroom stew on the hob today is rich and earthy enough but is hardly going to fill anyone. A couple of handfuls of spelt, boiled in lightly salted water and drained, will help turn what is essentially an accompaniment into something resembling a main course. Mushroom sauce becomes mushroom stew.