Полная версия

The Kitchen Diaries II

Enough for 6

JANUARY 2

A bunch of parsley

Few herbs have much to offer in winter, save bay. Even that is more aromatic when it is dried. They need the heat of the sun to concentrate the aromatic oils that lurk in their leaves and, sometimes, their stems. Parsley, though, has plenty of flavour even in the dead of winter, unless it has frozen in the ground. Parsley heals (John Gerard, the sixteenth-century herbalist, used it to quell stomach complaints) and has a high vitamin C content. Where basil stirs the senses, parsley brings us back to earth.

There is much talk about parsley stems and where they are useful. I don’t mind them in a leaf salad if they are fine and young, no thicker than a needle, but I don’t include them in ‘chopped parsley’, rough or otherwise. The stem occasionally carries an inherent bitterness and can be string-like too. Fastidiously stripping the leaves from their stems is something worth doing.

The stalks add a pleasing mineral quality to stock and soup (they possess a long tap root, like horseradish, that can stretch a foot or more into the earth) but you might prefer to add them towards the end of cooking, otherwise they will introduce a cabbagy note. Twenty minutes is time enough.

Wasted in its usual role as a garnish, if not downright pointless, this biennial, slow-germinating herb prefers rich soil, ideally slightly alkaline. Liking a little shade and winter shelter, it does well in my dampest bed, under the medlar tree. You can grow it from seed if you have the patience. I ‘rescue’ large pots of it from the supermarket and plant it in the garden just as others rescue battery hens.

There is little of interest in the cupboards and the fridge is as bare as I have seen it. But there is a granite-like lump of Parmesan in an airtight box in the fridge, a packet of rice in the cupboard and therefore the possibility of risotto. Parsley makes a surprisingly luxurious addition to rice as long as you are generous with the butter and cheese.

A parsley risotto with Parmesan crisps

Timing wise, you can manage to give the risotto its last ladle of stock, then start on the crisps. They will stay warm and crisp(ish) for long enough.

flat-leaf parsley: a good 50g

hot stock (chicken, turkey, vegetable at a push): a litre

a shallot or very small onion

butter: a thick slice

Arborio rice: 300g

a small glass of white wine or vermouth

To finish:

butter and grated Parmesan

For the Parmesan crisps:

finely grated Parmesan: 4 heaped tablespoons

Prepare the parsley. Pull the leaves from their stems, crack the stems with the back of a knife – their mineral scent is worth inhaling – then put them in a pan with the stock and bring to the boil. As the stock boils, turn the heat down to a low simmer. Finely chop the parsley leaves.

Peel and very finely chop the shallot and let it cook in the butter in a saucepan, without taking on any colour. Add the rice, turn the grains briefly in the butter till glossy, then pour in the wine and let it cook for a minute or two. Add a ladle of the stock. Stirring almost constantly, add another ladle of stock and continue to stir until the rice has soaked it all up. Now add the remaining stock, a ladle at a time, stirring pretty much all the time till the rice has soaked up the stock, the grains are plump and the texture creamy.

Stir in the chopped parsley, a thick slice of butter and a couple of handfuls of grated Parmesan. Season carefully.

For the Parmesan crisps, simply put heaped tablespoons of the grated Parmesan into a warm, non-stick frying pan. Press the cheese down flat with a palette knife and leave to melt. As soon as it has melted, turn once and continue cooking for a minute or so. Lift off with the palette knife and cool briefly. They will probably crisp up in seconds. Place on top of the risotto and serve.

Enough for 4

JANUARY 3

A crisp salad for a winter’s day

There are some pears and cheese left from Christmas, a couple of heads of crisp, hardy salad leaves still in fine fettle, and a plastic box of assorted sprouted seeds in the fridge. I put them together almost in desperation, yet what results is a salad that is both refreshing and uplifting, clean tasting and bright.

A salad of pears and cheese with sprouted seeds

Crisp, mild, light and fresh, this is the antidote to the big-flavoured salad. I prefer to use hard, glassy-fleshed pears straight from the fridge for this, rather than the usual ripe ones. Any sprouted seeds can be used, such as radish seeds, sunflower or mung beans. The easy-to-find bags of mixed sprouts are good here, too. The cheese is up to you. Something with a deep, fruity flavour is probably best, though I have used firm goat’s cheeses on occasion too. Rather than slicing it thickly, I remove shavings from the cheese with a vegetable peeler. A sort of contemporary ploughman’s lunch.

crisp pears: 2

bitter leaves such as frisée or trevise: 4 handfuls

firm, fruity cheese such as Berkswell: 150g

assorted sprouts (radish, alfalfa, sunflower, amaranth, etc.): a couple of handfuls

For the dressing:

natural yoghurt: 150ml

olive oil: 2 tablespoons

herbs, such as chervil, parsley, chives: a handful

Put the yoghurt into a bowl and whisk in the olive oil and a little salt and black pepper. Chop the herbs and stir them into the yoghurt.

Halve the pears, remove the cores and slice the pears thinly, then add them to the herb and yoghurt dressing.

Put the salad leaves in a serving dish. Pile the pears and their dressing on top. Using a vegetable peeler, shave off small, thin slices of the cheese and scatter them over the salad with the assorted sprouted seeds.

Enough for 2

JANUARY 5

Twelfth Night

The day that precedes Twelfth Night is often the darkest in my calendar. The sadness of taking down The Tree, packing up the mercury glass decorations in tissue and cardboard and rolling up the strings of tiny lights has long made my heart sink. Today I descend further than usual.

The rain is torrential and continuous. I clean the bedroom cupboards, make neat piles of books and untidy ones of clothes ready for the charity shop and make a list of major and minor jobs to do in the house over the next few months.

The local council collects discarded Christmas trees and recycles them for compost. I keep mine at home, cutting every branch from the main stem with secateurs and packing them into sacks. Over the next few weeks, the needles will fall and end their days around the blueberries and cloudberries in the garden. There is much that appeals about this annual cycle of the tree going back into the earth.

You would think that this day of darkness would be predictable enough for me to organise something to lift the spirits – dinner with friends or a day away from home. But the consequences of evergreens left in the house after Twelfth Night is too great a risk, even though this superstition is quite recent. So a day of dark spirits it is.

JANUARY 6

Epiphany

After yesterday’s darkness and self-indulgence, I open the kitchen door to find the garden refreshed after the rain. The air is suddenly sweet and clean, you can smell the soil, and the ivy and yew are shining bright. The dead leaves are blown away, the sky clear and white. There is a new energy and I want to cook again.

Today is an important day for those who grow their vegetables bio-dynamically, when the Three Kings preparation – a stir-up containing gold, frankincense and myrrh – is ground for an hour, then made into a paste with rain or pond water and offered to the land. Jane Scotter at Fern Verrow, the Herefordshire farmer from whom I buy the vegetables I cannot grow for myself (for which read most), says it smells ‘like a fine fruity Christmas cake’. ‘We do this to invite elemental life forces to help and guide us for the coming growing season. We ask for good things to happen and give the preparation as an offering to the earth and to give thanks for what the universe provides. It is a lovely thing to do and a chance to walk around the farm on a route not usually taken, holding thoughts of thanks and wishes to the farm on a spiritual level.’

Hippy-dippy hocus-pocus it may sound, but I have far less of a problem believing in this than I do many of the religious ceremonies practised by millions. Actually, much less so.

My energy and curiosity may be renewed but the larder isn’t. There is probably less food in the house than there has ever been. I trudge out to buy a few chicken pieces and a bag of winter greens to make a soup with the spices and noodles I have in the cupboard. What ends up as dinner is clear, bright and life-enhancing. It has vitality (that’s the greens), warmth (ginger, cinnamon) and it is economical and sustaining too. I suddenly feel ready for anything the New Year might throw at me.

Chicken noodle broth

chicken pieces and wings: 400g

black peppercorns: 8

star anise: 2

half a cinnamon stick

palm sugar: a scant teaspoon

fresh ginger: a small lump

fine, rice noodles: 200g

greens: about 400g

Thai or Vietnamese basil: a small handful

Make the chicken broth: put the chicken pieces and wings in a deep pan with the whole peppercorns, star anise, cinnamon stick and palm sugar. Peel the ginger, cut it into coins and add to the pan. Pour in a litre of water and bring to the boil. Turn down the heat and leave to simmer, at a gentle bubble, for twenty-five minutes. Remove from the heat and set aside.

Cook the noodles according to the instructions on the packet, then drain and set aside. Trim, wash and lightly steam the greens, then refresh under cold running water.

Divide the hot broth between four bowls, add the noodles and greens and finish with the basil.

Enough for 4

JANUARY 9

An old-fashioned ham, a new sauce

We have never been what you might call a ‘close’ family. A mother and father dead by the time I reached my late teens; a brother who emigrated; an uncle distanced by his obsession with religion. The family member I was closest to was a mischievous, twinkly-eyed aunt whose diet consisted solely of Cup-a-Soup, Bailey’s Irish Cream and a regular swig of Benylin. She lived to be a hundred, which puts the healthy-eating lobby firmly in its place.

When I was a child, she would take me to see my grandmother, a tiny, bent woman (I have inherited her shoulders), whose curtains were permanently drawn. My grandmother’s kitchen always had a pot on the stove and condensation running down the windows. The room was dark and smelled of boiling gammon and the smoke from the coal fire in the parlour. Yet despite the suggestion of food on its way, the scene was less than welcoming. No jolly granny with a laden tea table here, just a tired old lady, exhausted from a hard life spent bringing up five children on her own.

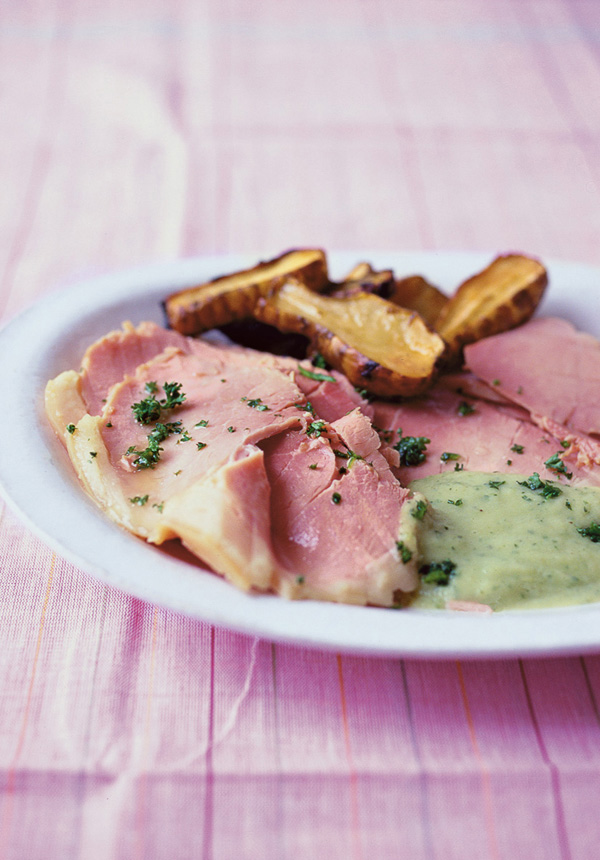

The smell of a ham puttering away in my own kitchen still reminds me of her – I suspect it always will – but now comes with a welcome. Thinly cut ham, warm from its cooking liquor, is a dish I too bring out to feed the hordes. Reasonably priced, presented on a large, oval plate with a jug of bright-green sauce, it seems to go a long way. A piece weighing just over a kilo will feed six, with leftovers for a winter salad the following day.

Parsley sauce is the old-school accompaniment to a dish of warm ham, but far from the only one. This week I put a bag of knobbly Jerusalem artichokes to good use, serving them roasted as a side dish to the ham and to add interest to the accompanying parsley sauce. Artichokes and parsley have an affinity with pork and with each other – I like to add bacon and the chopped herb to the roasted tubers, and snippets of crisp smoked streaky often find their way on to the surface of a bowl of parsley-freckled artichoke soup.

Any large lump of ham will do for slow cooking in water (I sometimes use apple juice). A ‘hand’ of pork, which comes from the top of the front legs and is what the French call jambonneau, is a sound cut for those who want to cook theirs on the bone. A piece of rolled and tied leg is easier to carve for a large number. A cut cooked on the bone shouldn’t give any trouble after an hour and a half on the stove. The meat should fall away with just a tug from a fork.

This is an unapologetically old-fashioned dish and the best accompaniments are those of a gentle nature: a quiet, cosseting sauce, some floury steamed potatoes and possibly the inclusion of some mild mustard, either in the sauce or on the edge of the plate. The recipe can be energised a bit in summer, when it will benefit from a bright-green, olive-oil-and herb-based sauce. But on a day as bone chilling as this, it needs an accompaniment as comforting as a goose-down duvet. We passed round a plate of apples and a lump of milky Cotherstone afterwards.

Ham with artichoke and parsley sauce

Some cooks like to soak their ham before cooking – a precaution against a salty ham. Overly salted hams seem to be a thing of the past, so I don’t bother. It is worth doing if you are unsure of your ham. I’m not convinced the sauce needs any cream but, should you wish to soften it further, 3 tablespoons of double cream will be enough. Serve with the roast artichokes below and large chunks of steamed potato.

a piece of boiling ham weighing about 1.5kg

onions: 2

bay leaves: 2

thyme: 4 short sprigs

black peppercorns: 15 or so

parsley stalks: 6–8

For the sauce:

Jerusalem artichokes: 250g

butter: a thin slice, about 20g

the onions from the ham liquor

parsley: a small bunch, about 15g

grain mustard: a tablespoon

a squeeze of lemon juice

Put the ham in a very large pot. Peel and halve the onions, then tuck them around the meat with the bay leaves, thyme sprigs and peppercorns (reserve the parsley stalks for adding later). Pour in enough water just to cover the meat – a good 2 litres. Bring to the boil, skim off the froth that rises to the surface, then leave to boil for a few minutes before turning down the heat to a simmer. Keep the liquid just below the boil (at a gentle simmer), partially covered with a lid, for an hour. Add the parsley stalks, then let it cook for a further half hour.

About half an hour or so before you are due to serve the ham, make the sauce (timing is not crucial here; both ham and sauce can keep warm without harm). Scrub and chop the artichokes. Warm the butter in a medium saucepan. Remove the onions from the ham pot with a draining spoon and put them into the butter with the artichokes. Let the artichokes cook for three or four minutes, then pour in 750ml water (you could add some of the ham cooking water if you wish, but no more than a third) and bring to the boil. Add a little salt, then turn the heat down and continue to let the artichokes simmer enthusiastically for twenty minutes or until they are on the verge of falling apart.

Roughly chop the parsley and add just over half of it to the artichokes, holding back the rest for later. Grind in a little black pepper. Simmer for five minutes or so, then remove from the heat. Whiz the sauce in a blender (never more than half filling it) till smooth and pale green. Check the seasoning, adding salt, pepper, the mustard, the reserved chopped parsley and a squeeze of lemon juice, if you wish (if you are adding cream, then you can add it now). Set aside till needed. It will take just a few minutes to reheat.

Remove the ham from its cooking liquor. Slice thinly and serve with the sauce and the roast artichokes below.

Enough for 6

Roast artichokes

You only need a couple of artichokes each. Trust me.

Jerusalem artichokes: 12 (about 800g)

olive oil

the juice of half a lemon

About an hour before the ham is due to be ready, set the oven at 180°C/Gas 4. Scrub the artichokes, slice them in half lengthways and put them in a baking dish. Pour over about 4 tablespoons of olive oil – just enough to moisten them – squeeze over the lemon, then grind over a little salt and black pepper. Toss gently and settle the artichokes cut-side down. Place in the preheated oven and bake for fifty minutes or until the outsides of the artichokes are golden and the insides meltingly soft.

JANUARY 12

Juniper – a cool spice for an arctic day

I consider leftovers as treasure, morsels of frugal goodness on which we can snack or feast, depending on the quantity. A few nuggets of leg meat from Sunday’s roast chicken are likely to be wolfed while standing at the fridge, but a decent bowlful of meat torn from the carcass could mean a filling for a pie (with onions, carrots, tarragon and cream). Today there is a thick wodge of leftover ham, its fat as white as the snow on the hedges outside, still sitting on its carving plate. A little dry round the edges from where I forgot to seal it in kitchen film, it is nevertheless going to be a base for tonight’s supper. On a warmer day, I might have eaten it sliced with a mound of crimson-fruited chutney and a bottle of beer, but the temperature is well below freezing and cold cuts and pickles will not hit the spot.

I am probably alone in holding juniper as one of my favourite spices. Its clean, citrus ‘n’ tobacco scent is both warming and refreshing. Where cumin, cinnamon and nutmeg offer us reassuring earthiness, juniper brings an arctic freshness and tantalising astringency. Growing on coniferous bushes and trees throughout the northern hemisphere and beyond, the berries, midnight blue when fresh, dry to an inky black. I delighted in finding them growing in Scotland amongst the heather. In a stoppered jar in a dark place, they keep their magic longer than almost any other spice.

The gin bottle aside, the berries are best known for their appearance in the fermented cabbage dish, sauerkraut (though I first met them in a dark, glossy sauce for pork chops). Their ability to slice through richness has led them to a life of pork recipes, from Swedish meatballs to pâté. I sometimes add them to a coarse, fat-speckled terrine for Christmas, dropping them into the mixture instead of the dusty-tasting mace. But their knife-edge quality makes them worth using with oily fish too, as in a marinade for fillets of mackerel (with sliced onions, cider vinegar, salt and dill) and a dry cure for sides of salmon (sea salt, dill and finely grated lemon zest).

Juniper berries are best used lightly squashed rather than finely ground. Crush them too much and they will bite rather than merely bark. Something you learn the hard way. A firm pounding with a pestle or the end of a rolling pin is all they need to release their oil. Their affinity with rich flesh is not confined to fat pork and oily fish. The berries have long been used to season game birds, especially towards the end of the season, when pigeon and partridge toughen and are brought to tenderness in a stew.

This (freezing) evening, as I crush the coal-black beads with the round end of a pestle, the piercing citrus notes come off the stone in cold, Nordic waves. They will invigorate my leftover ham, ripped into thick shards and tossed with onions and shredded white cabbage. Seasoned with sharp apples, brown sugar, cloves and white vinegar, my quick ham and cabbage fry up has its roots in the altogether more sophisticated sauerkraut.

A ham and cabbage fry up

A bottle of very cold beer would be appropriate here, if not downright compulsory.

butter: 30g

an onion cloves: 4

juniper berries: 15

a large, sharp apple: about 250g

white wine vinegar: 2 tablespoons

demerara sugar: a tablespoon

a hard, white cabbage: about 800g

leftover cooked ham: 250g

balsamic vinegar: a tablespoon

parsley: a small handful, roughly chopped

Melt the butter in a large, heavy-based pan over a low to moderate heat. Peel the onion and thinly slice into rounds, then add it to the butter. Throw in the cloves and the lightly crushed juniper berries (squash them flat with the side of a kitchen knife or in a pestle and mortar) and cover with a lid. Leave to cook, still over a low to moderate heat, with the occasional stir, for seven to ten minutes. The onion should be soft and lightly coloured.

Halve, core and thickly slice the apple. There is no need to peel it. Add it to the pan, then pour in the white wine vinegar and the sugar. Season with salt and pepper.

Shred the cabbage, not too finely, add it to the pan and mix lightly with the other ingredients. Cover with a tight lid and leave to soften over a lowish heat for about twenty minutes. The occasional stir will stop it sticking.

Tear or chop the ham into short, thick pieces. They are more satisfying if left large and uneven. Fold them into the cabbage, continue cooking for five minutes, then pour in the balsamic vinegar and toss in the chopped parsley. Pile into a warm dish and serve.

Enough for 2

JANUARY 13

The cook’s knife

There have been surprisingly few kitchen knives in my life. One, a thin, flexible filleting knife, has been with me since my cookery-school days; another from that era, its thin tang having come loose from the handle, is now used to gouge grass from between the garden paving stones. There is a fearsome carving blade from Sheffield, long the home of British knife making; a medium-sized, much-used Japanese knife that I regard as the perfect size and weight for me; and a tiny paring knife with a pale wooden handle that I hope stays with me to the grave.

The most used blade in my kitchen belongs to a heavy, 20cm cook’s knife. Thicker than is currently fashionable, its blade is made from carbon steel rather than the more usual stainless, which immediately marks me out as something of an old-fashioned cook. So be it. The blade, a mixture of iron and carbon, is the dull grey of a pencil lead, and heavily stained from years of lemon juice and vinegar. Its biggest sin is its habit of leaving an unpleasant grey streak on apples or tomatoes I have sliced with it, and occasionally on lemons too, but that, and the need to dry it thoroughly to prevent it rusting, is a small price to pay for a tool that is so ‘right’ it actually feels part of my body.

Picking up the right knife is like putting on a much-loved pullover. It may well have seen better days but the odd hole only seems to add to its qualities – like the wrinkles on a close friend. Price has little to do with it. My trusty vegetable peeler cost less than a loaf of bread and has dealt with a decade of potatoes and parsnips. And even if an expensive top-of-the-range Japanese knife is a pleasure to hold in the hand, it may not work any better for you than something as cheap as chips from the local ironmonger’s.