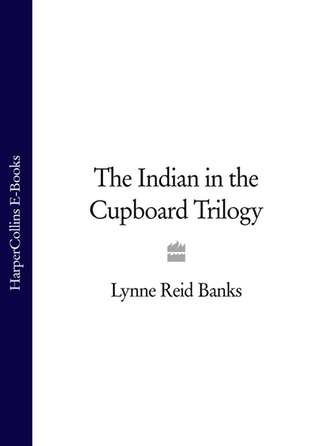

Полная версия

The Indian in the Cupboard Trilogy

“I don’t believe you killed so many people!” said Omri, shocked.

“Little Bull not lie. Great hunter. Great fighter. How show him son of Chief without many scalps?”

“Any white ones?” Omri ventured to ask.

“Some. French. Not take English scalps. Englishmen friends to Iroquois. Help Indian fight Algonquin enemy.”

Omri stared at him. He suddenly wanted to get away. “I’ll go and get you some – meat,” he said in a choking voice.

He went out of his room, closing the bedroom door behind him.

For a moment he did not move, but leant back against the door. He was sweating slightly. This was a bit more than he had bargained for!

Not only was his Indian no mere toy come to life; he was a real person, somehow magicked out of the past of over two hundred years ago. He was also a savage. It occurred to Omri for the first time that his idea of Red Indians, taken entirely from Western films, had been somehow false. After all, those had all been actors playing Indians, and afterwards wiping their war-paint off and going home for their dinners, not in tepees but in houses like his. Civilized men, pretending to be primitive, pretending to be cruel …

Little Bull was no actor. Omri swallowed hard. Thirty scalps … phew! Of course things were different in those days. Those tribes were always making war on each other, and come to that the English and French (whatever they thought they were doing, fighting in America) were probably no better, killing each other like mad as often as they could …

Come to that, weren’t soldiers of today doing the same thing? Weren’t there wars and battles and terrorism going on all over the place? You couldn’t switch on television without seeing news about people killing and being killed … Was thirty scalps, even including some French ones, taken hundreds of years ago, so very bad after all?

Still, when he tried to imagine Little Bull, full size, bent over some French soldier, holding his hair in one hand and running the point of his scalping-knife … Yuk!

Omri pushed away from the door and walked rather unsteadily downstairs. No wonder he had felt, from the first, slightly afraid of his Indian. He asked himself, swallowing repeatedly and feeling that just the same he might be sick, whether he wouldn’t do better to put Little Bull back in the cupboard, lock the door and turn him back into plastic, knife and all.

Down in the kitchen he ransacked his mother’s store-cupboard for a tin of meat. He found some corned beef at last and opened it with the tin-opener on the wall. He dug a chunk out with a teaspoon, put it absently into his own mouth and stood there chewing it.

The Indian hadn’t seemed very surprised about being in a giant house in England. He had shown that he was very superstitious, believing in magic and good and evil spirits. Perhaps he thought of Omri as – well, some kind of genie, or whatever Indians believed in instead. The wonder was that he wasn’t more frightened of him then, for genies, or giants, or Great Spirits, or whatever, were always supposed to be very powerful and often wicked. Omri supposed that if one happened to be the son of an Indian Chief, one simply didn’t get scared as easily as ordinary people. Especially, perhaps, if one had taken thirty scalps …

Maybe Omri ought to tell someone about Little Bull.

The trouble was that although grown-ups usually knew what to do, what they did was very seldom what children wanted to be done. What if he took the Indian to – say, some scientists, or – whoever knew about strange things like that, to question him and examine him and probably keep him in a laboratory or something of that sort? They would certainly want to take the cupboard away too, and then Omri wouldn’t be able to have any more fun with it at all.

Just when his mind was seething with ideas, such as putting in plastic bows and arrows, and horses, and maybe even other little people – well, no, probably that was too risky, who knew what sort you might land up with? They might start fighting each other! But still, he knew for certain he didn’t want to give up his secret, not yet, no matter how many Frenchmen had been scalped.

Having made his decision, for the moment anyway, Omri turned to go upstairs, discovering only halfway up that the tin of corned beef was practically empty. Still, there was a fair-sized bit left in the bottom. It ought to do.

Little Bull was nowhere to be seen, but when Omri called him softly he ran out from under the bed, and stood waving both arms up at Omri.

“Bring meat?”

“Yes.” Omri put it on the miniature plate he’d cut the night before and placed it before the Indian, who seized it in both hands and began to gnaw on it.

“Very good! Soft! Your wife cook this?”

Omri laughed. “I haven’t got a wife.”

The Indian stopped and looked at him. “Omri not got wife? Who grow corn, grind, cook, make clothes, keep arrows sharp?”

“My mother,” said Omri, grinning at the idea of her sharpening arrows. “Have you got a wife then?”

The Indian looked away After a moment he said, “No.”

“Why not?”

“Dead,” said Little Bull shortly.

“Oh.”

The Indian finished eating in silence and then stood up, wiping his greasy hands on his hair. “Now. Do magic. Make things for Little Bull.”

“What do you want?”

“Gun,” he answered promptly. “White man’s gun. Like English soldier.”

Omri’s brain raced. If a tiny knife could stab, a tiny gun could shoot. Maybe it couldn’t do much harm, but then again, maybe it could.

“No, no gun. But I can make you a bow and arrows. I’ll have to buy plastic ones, though. What else? A horse?”

“Horse!” Little Bull seemed surprised.

“Don’t you ride? I thought all Indians rode.”

Little Bull shook his head.

“English ride. Indians walk.”

“But wouldn’t you like to ride, like the English soldiers?”

Little Bull stood quite still, frowning, wrestling with this novel idea. At last he said, “Maybe. Yes. Maybe. Show horse. Then I see.”

“Okay.”

Again Omri rummaged in the biscuit tin. There were a number of horses here. Big heavy ones for carrying armoured knights. Smaller ones for pulling gun-carriages in the Napoleonic wars. Several cavalry horses – those might be the best. Omri ranged five or six of various sizes and colours before Little Bull, whose black eyes began to shine.

“I have,” he said promptly.

“You mean all of them?”

Little Bull nodded hungrily.

“No, that’s too much. I can’t have herds of horses galloping all over my room. You can choose one.”

“One?” said Little Bull sadly.

“One.”

Little Bull then made a very thorough examination of every horse, feeling their legs, running his hands over their rumps, looking straight into their plastic faces. At last he selected a smallish, brown horse with two white feet which had originally (as far as Omri could remember) carried an Arab, brandishing a curved sword at a platoon of French Foreign Legionnaires.

“Like English horse,” grunted Little Bull.

“And he’s got a saddle and bridle, which will become real too,” gloated Omri.

“Little Bull not want. Ride with rope, bare-back. Not like white soldier,” he added contemptuously, having another spit. “When?”

“I still don’t know how long it takes. We can start now.”

Omri lifted the cupboard onto the floor, shut the horse in and turned the key. Almost at once they could hear the clatter of tiny hooves on metal. They looked at each other with joyful faces.

“Open! Open door!” commanded Little Bull.

Omri lost no time in doing so. There, prancing and pawing the white paint, was a lovely, shiny-coated little brown Arab pony. As the door swung open he shied nervously, turning his face and pricking his ears so far forward they almost met over his forelock. His tiny nostrils flared, and his black tail plumed over his haunches as he gave a high, shrill neigh.

Little Bull cried out in delight.

In a moment he had vaulted over the bottom edge of the cupboard and, as the pony reared in fright, jumped into the air under its flying hooves and grasped the leather reins. The pony fought to free its head, but Little Bull hung on with both hands. Even as the pony plunged and bucked, the Indian had moved from the front to the side. Grasping the high pommel of the saddle he swung himself into it. He ignored the swinging stirrups, holding on by gripping with his knees.

The pony flung himself back on his haunches, then threw himself forward in a mighty buck, head low, heels flying. To Omri’s dismay, Little Bull, instead of clinging on somehow, came loose and flew through the air in a curve, landing on the carpet just beyond the edge of the cupboard.

Omri thought his neck must be broken, but he had landed in a sort of somersault, and was instantly on his feet again. The face he turned to Omri was shining with happiness.

“Crazy horse!” he cried with fierce delight.

The crazy horse was meanwhile standing quite still, reins hanging loose, looking watchfully at the Indian through wild, wide-apart eyes.

This time Little Bull made no sudden moves. He stood quite still for a long time, just looking back at the pony. Then, so slowly you could scarcely notice, he edged towards him, making strange hissing sounds between his clenched teeth which almost seemed to hypnotize the pony. Step by step he moved, softly, cautiously, until he and the pony stood almost nose to nose. Then, quite calmly, Little Bull reached up and laid his hand on the pony’s neck.

That was all. He did not hold the reins. The pony could have jumped away, but he didn’t. He raised his nose a little, so that he and the Indian seemed to be breathing into each other’s nostrils. Then, in a quiet voice, Little Bull said, “Now horse mine. Crazy horse mine.”

Still moving slowly, though not as slowly as before, he took the reins and moved alongside the pony. After a certain amount of fiddling he found out how to unbuckle the straps which held the Arabian saddle, and lifted it off, laying it on the floor. The pony snorted and tossed his head, but did not move. Hissing gently now, the Indian first leant his weight against the pony’s side, then lifted himself up by his arms until he was astride. Letting the reins hang loose on the pony’s neck, he squeezed with his legs. The pony moved forward, as tame and obedient as you please, and the pair rode once round the inside of the cupboard as if it had been a circus arena.

Suddenly Little Bull caught up the reins and pulled them to one side, turning the pony’s head. At the same time Little Bull kicked him sharply. The pony wheeled, and bounded forward towards the edge of the cupboard.

This metal rim, about two centimetres high, was up to the pony’s chest – like a five-barred gate to a full-sized horse. There was no room to ride straight at it, from the back of the cupboard to the front, so Little Bull rode diagonally – a very difficult angle, yet the pony cleared it in a flying leap.

Omri realized at once that the carpet was too soft for him – his feet simply sank into it like soft sand.

“Need ground. Not blanket,” said Little Bull sternly. “Blanket no good for ride.”

Omri looked at his clock. It was still only a little after six in the morning – at least another hour before anyone else would be up.

“I could take you outside,” he said hesitantly.

“Good!” said Little Bull. “But not touch pony. You touch, much fear.”

Omri quickly found a small cardboard box which had held a Matchbox lorry. It even had a sort of window through which he could see what was happening inside. He laid that on the carpet with the end flaps open.

Little Bull rode the pony into the box, and Omri carefully shut the end up and even more carefully lifted it. Then, in his bare feet, he carried the box slowly down the stairs and let himself out through the back door.

It was a lovely fresh summer morning. Omri stood on the back steps with the box in his hands, looking round for a suitable spot. The lawn wasn’t much good – the grass would be over the Indian’s head in most places. The terrace at the foot of the steps was no use at all, with its hard uneven bricks and the cracks between them. But the path was beaten earth and small stones – real riding-ground if they were careful. Omri walked to the path and laid the Matchbox carton down.

For a moment he hesitated. Could the Indian run away? How fast could such a small pony run? As fast as, say, a mouse? If so, and they wanted to escape, Omri wouldn’t be able to catch them. A cat, on the other hand, would. Omri knelt on the path in his pyjamas and put his face to the cellophane ‘window’. The Indian stood inside holding the pony’s head.

“Little Bull,” he said clearly, “we’re outdoors now. I’m going to let you out to ride. But remember – you’re not on your prairie now. There are mountain lions here, but they’re big enough to swallow you whole and the pony too. Don’t run away, you wouldn’t survive. Do you understand?”

Little Bull looked at him steadily and nodded. Omri opened the flap and Indian and pony stepped out into the morning sunlight.

4

The Great Outdoors

Both horse and man seemed to sniff the air, tasting its freshness and testing it for danger at the same time. The pony was still making circles with his nose when Little Bull sprang onto his back.

The pony, startled, reared slightly, but this time Little Bull clung on to his long mane. The pony’s front feet had no sooner touched the path than he was galloping. Omri leapt to his feet and gave chase.

The pony’s speed was remarkable, but Omri found that by running along the lawn beside the path he could keep up quite easily. The ground was dry and as Indian and pony raced along, a most satisfying cloud of dust rose behind them so that Omri could easily imagine that they were galloping across some wild, unbroken territory …

More and more, he found, he was able to see things from the Indians point of view. The little stones on the path became huge boulders which had to be dodged, weeds became trees, the lawn’s edge an escarpment twice the height of a man … As for living things, an ant, scuttling across the pony’s path, made him shy wildly. The shadow of a passing bird falling on him brought him to a dead stop, crouching and cowering as a full-sized pony might if some huge bird of prey swooped at him. Once again, Omri marvelled at the courage of Little Bull, faced with all these terrors.

But it was not the courage of recklessness. Little Bull clearly recognized his peril and, when he had had his gallop, turned the pony’s head and came trotting back to Omri, who crouched down to hear what he said.

“Danger,” said the Indian. “Much. I need bow, arrows, club. Maybe gun?” he asked pleadingly. Omri shook his head. “Then Indian weapons.”

“Yes,” said Omri. “You need those. I’ll find them today. In the meantime we’d better go back in the house.”

“Not go shut-in place! Stay here. You stay, drive off wild animals.”

“I can’t. I’ve got to go to school.”

“What school?”

“A place where you learn.”

“Ah! Learn. Good,” said Little Bull approvingly. “Learn law of tribe, honour for ancestors, ways of the spirits?”

“Well … something like that.”

Little Bull was clearly reluctant to return to the house, but he had the sense to realize he couldn’t cope outside by himself. He galloped back along the path, with Omri running alongside, and dismounting, re-entered the carton.

Omri was just carrying it up the back steps when the back door suddenly opened and there was his father.

“Omri! What on earth are you doing out here in your pyjamas? And nothing on your feet, you naughty boy! What are you up to?”

Omri clutched the box to him so hard in his fright that he felt the sides bend and quickly released his hold. He felt himself break into a sweat.

“Nothing – I – couldn’t sleep. I wanted to go out.”

“What’s wrong with putting on your slippers, at least?”

“Sorry. I forgot.”

“Well, hurry up and get dressed now.”

Omri rushed upstairs and, panting, laid the box on the floor. He opened the flap. The pony rushed out alone, and stood under the table, whinnying and trembling – he had had a rough ride. Full of foreboding, Omri bent down and peered into the box. Little Bull was sitting in a corner of it, hugging his leg, which Omri saw, to his horror, was bleeding right through his buckskin leggings.

“Box jump. Pony get fear. Kick Little Bull,” said the Indian, who, though calm, was clearly in pain.

“Oh, I’m sorry!” cried Omri. “Can you come out? I’ll see what I can do.”

Little Bull stood up and walked out of the box. He did not let himself limp.

“Take off your leggings – let me see the cut,” said Omri.

The Indian obeyed him and stood in his breech-cloth. On his tiny leg was a wound from the pony’s hoof, streaming blood onto the carpet. Omri didn’t know what to do, but Little Bull did.

“Water,” he ordered. “Cloths.”

Omri, through his panic, forced himself to think clearly. He had water in a toothmug by his bed, but that would not be clean enough to wash a wound. His mother had some Listerine in her medicine cupboard; when any of the boys had a cut she would add a few drops to some warm water and that was a disinfectant.

Omri dashed to the bathroom, and with trembling hands did what he had seen his mother do. He took a small piece of cotton-wool. What could be used as a bandage he had no idea at all. But he hurried back with the water, and poured some into the Action Man’s mess-tin. The Indian tore off a minute wisp of cotton-wool and dipped it into the liquid and applied it to his leg.

The Indian’s eyes opened wide though he did not wince. “This not water! This fire!”

“It’s better than water.”

“Now tie,” said the Indian next. “Hold in blood.”

Omri looked round desperately. A bandage small enough for a wound like that! Suddenly his eyes lighted on the biscuit tin. There, lying on top, was a First World War soldier with the red armband of a medical orderly. In his hand was a doctor’s bag with a red cross on it. What might that contain if Omri could make it real?

Not stopping to think too far ahead, he snatched the figure up and thrust it into the cupboard, shutting the door and turning the key.

A moment later a thin English voice from inside called: “Here! Where am I? Come back you blokes – don’t leave a chap alone in the dark!”

5

Tommy

Omri felt himself grow weak. What an idiot he’d been! Not to have realized that the man and not just the medical bag would be changed! Or had he? After all, what did he need more just then than a bandage of the right size for the Indian? Someone of the right size to put it on! And, unless he was sadly mistaken, that was just what was waiting inside the magic cupboard.

He unlocked the door.

Yes, there he was – pink cheeked, tousle-headed under his army cap, his uniform creased and mud-spattered and blood-stained, looking angry, frightened and bewildered.

He rubbed his eyes with his free hand.

“Praise be for a bit of daylight, anyway,” he said. “What the—”

Then he opened his eyes and saw Omri.

Omri actually saw him go white, and his knees gave way under him. He uttered a few sounds, half curses and half just noises. He dropped the bag and hid his face for a moment. Omri said hastily:

“Please don’t be afraid. It’s all right. I—” Then he had an absolute inspiration! “I’m a dream you’re having. I won’t hurt you, I just want you to do something for me, and then you’ll wake up.”

Slowly the little man lowered his hands and looked up again.

“A dream, is it? Well … I should’ve guessed. Yes, of course. It would be. The whole rotten war’s nightmare enough, though, without giants and – and—” He stared round Omri’s room. “Still and all, perhaps it’s a change for the better. At least it’s quiet here.”

“Can you bring your bag and climb out? I need your help.”

The soldier now managed a rather sickly smile and tipped his cap in a sort of salute. “Right you are! With you in a tick,” he said, and picking up the bag, clambered over the edge of the cupboard.

“Stand on my hand,” Omri commanded.

The soldier did not hesitate a moment, but swung himself up by hooking his free arm round Omri’s little finger. “Bit of a lark, this,” he remarked. “I won’t half enjoy telling the fellows about this dream of mine in the trenches tomorrow!”

Omri carried him to the spot where Little Bull sat on the carpet holding his leg which was still bleeding. The soldier stepped down and stood, knee-deep in carpet-pile, staring.

“Well, I’ll be jiggered!” he breathed. “A bloomin’ redskin! This is a rum dream and no mistake! And wounded, too. Well, I suppose that’s my job, is it – to patch him up?”

“Yes, please,” said Omri.

Without more ado, the soldier put the bag on the floor and snapped open its all-but-invisible catches. Omri leant over to see. Now he really did need a magnifying glass, and so badly did he want to see the details of that miniature doctor’s bag that he risked sneaking into Gillon’s room (Gillon always slept late, and anyway it wasn’t seven o’clock yet) and pinching his from his secret drawer.

By the time he got back to his own room, the soldier was kneeling at Little Bull’s feet, applying a neat tourniquet to the top of his leg. Omri peered through the magnifying glass into the open bag. It was amazing – everything was there, bottles, pill-boxes, ointments, some steel instruments including a tiny hypodermic needle, and as many rolls of bandages as you could want.

Omri then ventured to look at the wound. Yes, it was quite deep – the pony must have given him a terrific kick.

That reminded him – where was the pony? He looked round in a fright. But he soon saw it, trying forlornly to eat the carpet. “I must get it some grass,” thought Omri, meanwhile offering it a small piece of stale bread which it ate gratefully, and then some water in a tin lid. It was odd how the pony was not frightened of him. Perhaps it couldn’t see him very well.

“There now, he’ll do,” said the soldier, getting up.

Omri looked at the Indian’s leg through his magnifying glass. The wound was bandaged beautifully. Even Little Bull was examining it with obvious approval.

“Thank you very much,” said Omri. “Would you like to wake up now?”

“Might as well, I suppose. Not that there’s much to look forward to except mud and rats and German shells coming over … Still. Got to win the war, haven’t we? Can’t desert, even into a dream, not for long that is – duty calls and all that, eh?”

Omri gently picked him up and put him into the cupboard.

“Goodbye,” he said. “Perhaps, some time, you could dream me again.”

“A pleasure,” said the soldier cheerfully. “Tommy Atkins, at your service. Any night, except when there’s an attack on – none of us gets any sleep to speak of then.” And he gave Omri a smart salute.

Regretfully Omri shut and locked the door. He was tempted to keep the soldier, but it was too complicated just now. Anyway he could always bring him back to life again if he liked … A moment or two later he opened the door again to check. There was the orderly, bag in hand, standing just as Omri had last seen him, at the salute. Only now he was plastic again.