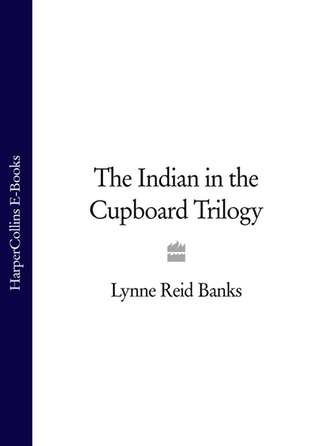

Полная версия

The Indian in the Cupboard Trilogy

“All the best cooks are men,” he retorted. “Come on, you’re going to eat with Boone.”

Little Bull’s laughter died instantly.

“Who Boone?”

“You know who he is. The cowboy.”

The Indian’s hands came off his hips and one of them went for his knife.

“Oh, knock it off, Little Bull! Have a truce for breakfast, otherwise you won’t get any.”

Leaving him with that thought to chew over, Omri crossed to the crate, in which Boone was grooming his white horse with a wisp of cloth he’d found clinging to a splinter. He’d taken off the little saddle, but the bridle was still on.

“Boone! I’ve brought something to eat,” said Omri.

“Yup. Ah thought Ah smelt some’n good,” said Boone. “Let’s git to it.”

Omri put his hand down. “Climb on.”

“Ah, shucks – where’m Ah goin’? Why cain’t Ah eat in mah box, where it’s safe?” whined Boone. But he clambered up into Omri’s palm and sat grumpily with his back against his middle finger.

“You’re going to eat with the Indian,” said Omri.

Boone leapt up so suddenly he nearly fell off, and had to grab hold of a thumb to steady himself.

“Hell, no, Ah ain’t!” he yelled. “You just put me down, son, ya hear? I ain’t sharin’ m’vittles with no lousy scalp-snafflin’ Injun and that’s m’last word!” It was, as it happened, his last word before being set down within a few centimetres of his enemy on the seed-tray.

They both bent their legs into crouches, as if uncertain whether to leap at each other’s throats or turn and flee. Omri hurriedly spooned up some egg and beans and held it between them.

“Smell that!” he ordered them. “Now you eat together or you don’t get any at all, so make up your minds to it. You can start fighting again afterwards if you must.”

He took a bit of clean paper and laid it, like a table cloth, under the spoon. Then he broke off some crumbs of bread crust and pushed a little into each of their hands. Still with their eyes fixed on each other’s faces, Indian and cowboy sidled towards the big, steaming ‘bowl’ of food from opposite sides. Little Bull, after hesitating, was first to shoot his arm out and dip the bread into the egg. The sudden movement startled Boone so much he let out a yell and tried to run, but Omri’s hand was blocking the way.

“Don’t be silly, Boone,” he said firmly.

“Ah ain’t bein’ silly! Them Injuns ain’t jest ornery and savage. Them’s dirty. And Ah ain’t eatin’ from the same bowl as no—”

“Boone,” said Omri quietly. “Little Bull is no dirtier than you. You should see your own face.”

“Is that mah fault? What kinda hallucy-nation are ya, anyways, tellin’ me Ah’m dirty when ya didn’t bring me no washin’ water?”

This was a fair complaint, but Omri wasn’t about to lose the argument on a side issue.

“You can have some after breakfast. But if you don’t agree to eat with my Indian, I’m going to tell him your nickname.”

The cowboy’s face fell. “Now that ain’t fair. That plumb ain’t no ways fair,” he muttered. But hunger was getting the better of him anyway, so, grumbling and swearing under his breath, he turned back and marched to his side of the spoon. By this time Little Bull was seated cross-legged on the piece of paper, a hunk of bean in one hand and a mess of egg in the other, eating heartily. Seeing this, Boone lost no time in tucking in, eyeing the Indian, who ignored him.

“Whur’s muh cawfee?” he complained after he’d eaten a few bites. “Ah cain’t start the day till Ah’ve had muh jug o’ cawfee!”

Omri had completely forgotten about coffee, but he was beginning to be pretty well fed up with being bossed around by ungrateful little men, so he settled down to eat the remains of the food and simply said, “Well, you’ll have to start this one without any.”

Little Bull finished his breakfast and stood up.

“Now we fight,” he announced, and reached for his knife.

Omri expected Boone to leap up and run, but he didn’t. He just sat there munching bread and beans.

“Ah ain’t finished yit,” he said. “Ain’t gonna fight till Ah’m plumb full o’vittles. So you kin jest sit down and wait, Redskin.”

Omri laughed. “Good for you, Boone! Take it easy, Little Bull. Don’t forget your promise.”

Little Bull scowled. But he sat down again.

Boone ate and ate. It was hard not to suspect, after a while, that he was eating as much and as slowly as possible, to put off the moment when he would have to fight.

At last, very reluctantly, he scraped the last bit of egg from the spoon, wiped his hands on the side of his trousers, and stood up. Little Bull was on his feet instantly. Omri stood ready to part them.

“Looka here, Injun,” said Boone. “If we’re gonna fight, we’re gonna fight fair. Probably ain’t even a word for ‘fair’ in your language, but Ah’m here to tell ya, with me it’s fight fair or don’t fight a-tall.”

“Little Bull fight fair, kill fair, scalp fair.”

“You ain’t gonna scalp nobody. Less’n ya take it off with yer teeth.”

For answer, Little Bull raised his knife, which flashed in the morning light. Omri, his hands on his knees, waited.

“Yeah, Ah see it. But you ain’t gonna have it much longer. And why aincha? Because Ah ain’t got one. Ah only got m’gun, and m’gun’s run plumb outa bullets. What Ah got, and all Ah got, is m’fists. Oh – and one other thing. Ah got mah hallucy-nation here.” He waved a hand at Omri without taking his eyes off Little Bull for a second. “And Ah know he don’t want to see this here purty red scalp o’mine hangin’ from no stinkin’ redskin’s belt. So if Ah fight, it’s gonna be fist to fist, face to face – man to man, Injun! D’ja hear me? No weapons! Jest us two, and let’s see if a white man cain’t lick a red man in a fair fight. Less’n mebbe – jest mebbe – you ain’t red a-tall, but yeller?” And Boone stepped round the bowl of the spoon, threw his empty gun on the ground, and put up his fists like a boxer.

Little Bull was nonplussed. He lowered his knife and stared at Boone. Whether Little Bull had completely understood the cowboy’s strange speech was doubtful, but he couldn’t mistake the gesture of throwing the gun away. As Boone began to dance round him, fists up, making little mock jabs towards his face, Little Bull was getting madder and madder. He made a sudden swipe at him with his knife. Boone jumped back.

“Oh, you naughty Injun! Ah see Ah’ll have to set mah hallucy-nation on to you!”

But Omri didn’t have to do anything. Little Bull had got the message. Throwing down the knife in a fury, he hurled himself on to Boone.

What followed was not a fist fight, or a wrestling match, or anything so well organized. It was just an all-in, no-holds-barred two-man war. They rolled on the ground pummelling, kicking and butting with their heads. At one point Omri thought he saw Boone trying to bite. Maybe he succeeded, because Little Bull suddenly let him go and Boone rolled away swift as a barrel down a slope and on to his legs and then, with a spring, like a bow-legged panther on to the Indian again. Feet first.

Little Bull let out a noise like ‘OOOF!’ – caught Boone by both ankles, and heaved him off. Little Bull picked up a clod of compost and flung it after him, catching him full in the face. Then Little Bull got up and ran at him, holding both fists together and swinging them as he had swung the battle-axe. They caught the cowboy a heavy whack on the ear which sent him flying to one side. But as he flew, he caught Little Bull a blow in the chest with one boot. That left them both on the ground.

The next moment each of the men found himself pinned down by a giant finger.

“All right, boys. That’s enough,” said Omri, in his father’s firm end-of-the-fight voice. “It’s a draw. Now you must get cleaned up for school.”

11

School

He brought them a low type of egg-cup full of hot water and a corner of soap cut off a big cake, to wash with. They stood one on each side of it. Little Bull, already naked to the waist, lost no time in plunging his arms in and began energetically rubbing the whole of the top part of his body with his wet hands, throwing water everywhere. He made a lot of noise about it and seemed to be enjoying himself, though he ignored the soap.

Boone was a different matter. Omri had already noticed that Boone was none too fussy about being clean, and in fact didn’t look as if he’d washed or shaved for weeks. Now he approached the hot water gingerly, eyeing Omri as if to see how little washing he could actually get away with.

“Come on, Boone! Off with that shirt, you can’t wash your neck with a shirt on,” said Omri briskly, echoing his mother.

With extreme reluctance, shivering theatrically, Boone dragged off his plaid shirt, keeping his hat on.

“I should think your hair could do with a wash too,” said Omri.

Boone stared at him.

“Wash mah hair?” he asked incredulously. “Washin’ hair’s fur wimmin, ’tain’t fer men!” But he did consent to rub his hands lightly over the piece of soap, although grimacing hideously as if it were some slimy dead thing. Then he rinsed them hastily, smeared some water on his face, and reached for his shirt without even drying himself.

“Boone!” said Omri sternly. “Just look at Little Bull! You called him dirty, but at least he’s washing himself thoroughly! Now you just do something about your neck and – well, under your arms.”

Boone’s look was now one of stark horror.

“Under mah arms!”

“And your chest I should think. I’m not taking you to school all sweaty.”

“Hell! Don’t you go runnin’ down sweat! It’s sweat that keeps a man clean!”

After a lot of bullying, Omri managed to get him to wash at least a few more bits of himself.

“You’ll have to wash your clothes some time, too,” he said.

But this was too much for Boone.

“Ain’t nobody gonna touch muh duds, and that’s final,” he said. “Ain’t bin washed since ah bought ’em. Water takes all the stuffin’ outa good cloth. Without all the dust ’n’ sweat they don’t keep ya warm no more.”

At last they were ready, and Omri pocketed them and ran down to breakfast. He felt tense with excitement. He’d never carried them around the house before. It was risky, but not so risky as taking them to school – he felt that having family breakfast with them secretly in his pocket was like a training for taking them to school.

Breakfast in his house was often a dicey meal anyway, with everybody more or less bad-tempered. Today, for instance, Adiel had lost his football shorts and was blaming everybody in turn, and their mother had just discovered that Gillon, contrary to his assurances the night before when he had wanted to watch television, had not finished his homework. Their father was grumpy because he had wanted to do some gardening and it was raining yet again.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.