полная версия

полная версияContributions to the Theory of Natural Selection

It would thus appear as if there must be (or once have been) in the island of Celebes, some peculiar enemy to these larger-sized butterflies which does not exist, or is less abundant, in the surrounding islands. Increased powers of flight, or rapidity of turning, was advantageous in baffling this enemy; and the peculiar form of wing necessary to give this would be readily acquired by the action of “natural selection” on the slight variations of form that are continually occurring.

Such an enemy one would naturally suppose to be an insectivorous bird; but it is a remarkable fact that most of the genera of Fly-catchers of Borneo and Java on the one side (Muscipeta, Philentoma,) and of the Moluccas on the other (Monarcha, Rhipidura), are almost entirely absent from Celebes. Their place seems to be supplied by the Caterpillar-catchers (Graucalus, Campephaga, &c.), of which six or seven species are known from Celebes and are very numerous in individuals. We have no positive evidence that these birds pursue butterflies on the wing, but it is highly probable that they do so when other food is scarce. Mr. Bates has suggested to me that the larger Dragonflies (Æshna, &c.) prey upon butterflies; but I did not notice that they were more abundant in Celebes than elsewhere. However this may be, the fauna of Celebes is undoubtedly highly peculiar in every department of which we have any accurate knowledge; and though we may not be able satisfactorily to trace how it has been effected, there can, I think, be little doubt that the singular modification in the wings of so many of the butterflies of that island is an effect of that complicated action and reaction of all living things upon each other in the struggle for existence, which continually tends to readjust disturbed relations, and to bring every species into harmony with the varying conditions of the surrounding universe.

But even the conjectural explanation now given fails us in the other cases of local modification. Why the species of the Western islands should be smaller than those further east,—why those of Amboyna should exceed in size those of Gilolo and New Guinea—why the tailed species of India should begin to lose that appendage in the islands, and retain no trace of it on the borders of the Pacific,—and why, in three separate cases, the females of Amboyna species should be less gaily attired than the corresponding females of the surrounding islands,—are questions which we cannot at present attempt to answer. That they depend, however, on some general principle is certain, because analogous facts have been observed in other parts of the world. Mr. Bates informs me that, in three distinct groups, Papilios which on the Upper Amazon and in most other parts of South America have spotless upper wings obtain pale or white spots at Pará and on the Lower Amazon; and also that the Æneas-group of Papilios never have tails in the equatorial regions and the Amazons valley, but gradually acquire tails in many cases as they range towards the northern or southern tropic. Even in Europe we have somewhat similar facts; for the species and varieties of butterflies peculiar to the island of Sardinia are generally smaller and more deeply coloured than those of the mainland, and the same has recently been shown to be the case with the common tortoiseshell butterfly in the Isle of Man; while Papilio Hospiton, peculiar to the former island, has lost the tail, which is a prominent feature of the closely allied P. Machaon.

Facts of a similar nature to those now brought forward would no doubt be found to occur in other groups of insects, were local faunas carefully studied in relation to those of the surrounding countries; and they seem to indicate that climate and other physical causes have, in some cases, a very powerful effect in modifying specific form and colour, and thus directly aid in producing the endless variety of nature.

Mimicry

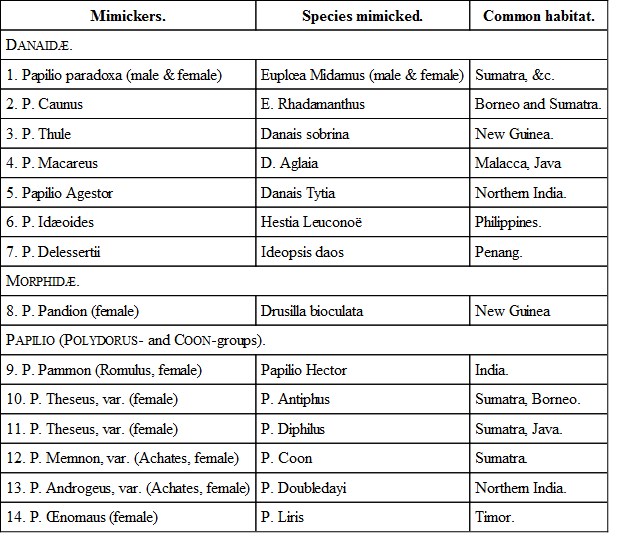

Having fully discussed this subject in the preceding essay, I have only to adduce such illustrations of it, as are furnished by the Eastern Papilionidæ, and to show their bearing upon the phenomena of variation already mentioned. As in America, so in the Old World, species of Danaidæ are the objects which the other families most often imitate. But besides these, some genera of Morphidæ and one section of the genus Papilio are also less frequently copied. Many species of Papilio mimic other species of these three groups so closely that they are undistinguishable when on the wing; and in every case the pairs which resemble each other inhabit the same locality.

The following list exhibits the most important and best marked cases of mimicry which occur among the Papilionidæ of the Malayan region and India:—

We have, therefore, fourteen species or marked varieties of Papilio, which so closely resemble species of other groups in their respective localities, that it is not possible to impute the resemblance to accident. The first two in the list (Papilio paradoxa and P. Caunus) are so exactly like Euplœa Midamus and E. Rhadamanthus on the wing, that although they fly very slowly, I was quite unable to distinguish them. The first is a very interesting case, because the male and female differ considerably, and each mimics the corresponding sex of the Euplœa. A new species of Papilio which I discovered in New Guinea resembles Danais sobrina, from the same country, just as Papilio Marcareus resembles Danais Aglaia in Malacca, and (according to Dr. Horsfield’s figure) still more closely in Java. The Indian Papilio Agestor closely imitates Danais Tytia, which has quite a different style of colouring from the preceding; and the extraordinary Papilio Idæoides from the Philippine Islands, must, when on the wing, perfectly resemble the Hestia Leuconoë of the same region, as also does the Papilio Delessertii imitate the Ideopsis daos from Penang. Now in every one of these cases the Papilios are very scarce, while the Danaidæ which they resemble are exceedingly abundant—most of them swarming so as to be a positive nuisance to the collecting entomologist by continually hovering before him when he is in search of newer and more varied captures. Every garden, every roadside, the suburbs of every village are full of them, indicating very clearly that their life is an easy one, and that they are free from persecution by the foes which keep down the population of less favoured races. This superabundant population has been shown by Mr. Bates to be a general characteristic of all American groups and species which are objects of mimicry; and it is interesting to find his observations confirmed by examples on the other side of the globe.

The remarkable genus Drusilla, a group of pale-coloured butterflies, more or less adorned with ocellate spots, is also the object of mimicry by three distinct genera (Melanitis, Hyantis, and Papilio). These insects, like the Danaidæ, are abundant in individuals, have a very weak and slow flight, and do not seek concealment, or appear to have any means of protection from insectivorous creatures. It is natural to conclude, therefore, that they have some hidden property which saves them from attack; and it is easy to see that when any other insects, by what we call accidental variation, come more or less remotely to resemble them, the latter will share to some extent in their immunity. An extraordinary dimorphic form of the female of Papilio Ormenus has come to resemble the Drusillas sufficiently to be taken for one of that group at a little distance; and it is curious that I captured one of these Papilios in the Aru Islands hovering along the ground, and settling on it occasionally, just as it is the habit of the Drusillas to do. The resemblance in this case is only general; but this form of Papilio varies much, and there is therefore material for natural selection to act upon, so as ultimately to produce a copy as exact as in the other cases.

The eastern Papilios allied to Polydorus, Coon, and Philoxenus, form a natural section of the genus resembling, in many respects, the Æneas-group of South America, which they may be said to represent in the East. Like them, they are forest insects, have a low and weak flight, and in their favourite localities are rather abundant in individuals; and like them, too, they are the objects of mimicry. We may conclude, therefore, that they possess some hidden means of protection, which makes it useful to other insects to be mistaken for them.

The Papilios which resemble them belong to a very distinct section of the genus, in which the sexes differ greatly; and it is those females only which differ most from the males, and which have already been alluded to as exhibiting instances of dimorphism, which resemble species of the other group.

The resemblance of P. Romulus to P. Hector is, in some specimens, very considerable, and has led to the two species being placed following each other in the British Museum Catalogues and by Mr. E. Doubleday. I have shown, however, that P. Romulus is probably a dimorphic form of the female P. Pammon, and belongs to a distinct section of the genus.

The next pair, Papilio Theseus, and P. Antiphus, have been united as one species both by De Haan and in the British Museum Catalogues. The ordinary variety of P. Theseus found in Java almost as nearly resembles P. Diphilus, inhabiting the same country. The most interesting case, however, is the extreme female form of P. Memnon (figured by Cramer under the name of P. Achates), which has acquired the general form and markings of P. Coon, an insect which differs from the ordinary male P. Memnon, as much as any two species which can be chosen in this extensive and highly varied genus; and, as if to show that this resemblance is not accidental, but is the result of law, when in India we find a species closely allied to P. Coon, but with red instead of yellow spots (P. Doubledayi), the corresponding variety of P. Androgeus (P. Achates, Cramer, 182, A, B,) has acquired exactly the same peculiarity of having red spots instead of yellow. Lastly, in the island of Timor, the female of P. Œnomaus (a species allied to P. Memnon) resembles so closely P. Liris (one of the Polydorus-group), that the two, which were often seen flying together, could only be distinguished by a minute comparison after being captured.

The last six cases of mimicry are especially instructive, because they seem to indicate one of the processes by which dimorphic forms have been produced. When, as in these cases, one sex differs much from the other, and varies greatly itself, it may happen that occasionally individual variations will occur having a distant resemblance to groups which are the objects of mimicry, and which it is therefore advantageous to resemble. Such a variety will have a better chance of preservation; the individuals possessing it will be multiplied; and their accidental likeness to the favoured group will be rendered permanent by hereditary transmission, and, each successive variation which increases the resemblance being preserved, and all variations departing from the favoured type having less chance of preservation, there will in time result those singular cases of two or more isolated and fixed forms, bound together by that intimate relationship which constitutes them the sexes of a single species. The reason why the females are more subject to this kind of modification than the males is, probably, that their slower flight, when laden with eggs, and their exposure to attack while in the act of depositing their eggs upon leaves, render it especially advantageous for them to have some additional protection. This they at once obtain by acquiring a resemblance to other species which, from whatever cause, enjoy a comparative immunity from persecution.

Concluding remarks on Variation in Lepidoptera

This summary of the more interesting phenomena of variation presented by the eastern Papilionidæ is, I think, sufficient to substantiate my position, that the Lepidoptera are a group that offer especial facilities for such inquiries; and it will also show that they have undergone an amount of special adaptive modification rarely equalled among the more highly organized animals. And, among the Lepidoptera, the great and pre-eminently tropical families of Papilionidæ and Danaidæ seem to be those in which complicated adaptations to the surrounding organic and inorganic universe have been most completely developed, offering in this respect a striking analogy to the equally extraordinary, though totally different, adaptations which present themselves in the Orchideæ, the only family of plants in which mimicry of other organisms appears to play any important part, and the only one in which cases of conspicuous polymorphism occur; for as such we must class the male, female, and hermaphrodite forms of Catasetum tridentatum, which differ so greatly in form and structure that they were long considered to belong to three distinct genera.

Arrangement and Geographical Distribution of the Malayan Papilionidæ

The genera Ornithoptera and Leptocircus are highly characteristic of Malayan entomology, but are uniform in character and of small extent. The genus Papilio, on the other hand, presents a great variety of forms, and is so richly represented in the Malay Islands, that more than one-fourth of all the known species are found there. It becomes necessary, therefore, to divide this genus into natural groups before we can successfully study its geographical distribution.

Owing principally to Dr. Horsfield’s observations in Java, we are acquainted with a considerable number of the larvæ of Papilios; and these furnish good characters for the primary division of the genus into natural groups. The manner in which the hinder wings are plaited or folded back at the abdominal margin, the size of the anal valves, the structure of the antennæ, and the form of the wings are also of much service, as well as the character of the flight and the style of colouration. Using these characters, I divide the Malayan Papilios into four sections, and seventeen groups, as follows:—

Genus Ornithoptera.

a. Priamus-group. Black and Green.

c. Brookeanus-group. Black and Green.

b. Pompeus-group. Black and yellow.

Genus Papilio.

Larvæ short, thick, with numerous fleshy tubercles; of a purplish colour.

a. Nox-group. Abdominal fold in male very large; anal valves small, but swollen; antennæ moderate; wings entire, or tailed; includes the Indian Philoxenus-group.

b. Coon-group. Abdominal fold in male small; anal valves small, but swollen; antennæ moderate; wings tailed.

c. Polydorus-group. Abdominal fold in male small, or none; anal valves small or obsolete, hairy; wings tailed or entire.

Larvæ with third segment swollen, transversely or obliquely banded; pupa much bent. Imago with abdominal margin in male plaited, but not reflexed; body weak; antennæ long; wings much dilated, often tailed.

d. Ulysses-group.

e. Peranthus-group. Protenor-group (Indian) is somewhat intermediate between these, and is nearest to the Nox-group.

f. Memnon-group. Protenor-group (Indian) is somewhat intermediate between these, and is nearest to the Nox-group.

g. Helenus-group.

h. Erectheus-group.

i. Pammon-group.

k. Demolion-group.

Larvæ subcylindrical, variously coloured. Imago with abdominal margin in male plaited, but not reflexed; body weak; antennæ short, with a thick curved club; wings entire.

l. Erithonius-group. Sexes alike, larva and pupa something like those of P. Demolion.

m. Paradoxa-group. Sexes different.

n. Dissimilis-group. Sexes alike; larva bright-coloured; pupa straight, cylindric.

Larvæ elongate, attenuate behind, and often bifid, with lateral and oblique pale stripes, green. Imago with the abdominal margin in male reflexed, woolly or hairy within; anal valves small, hairy; antennæ short, stout; body stout.

o. Macareus-group. Hind wings entire.

p. Antiphates-group. Hind wings much tailed (swallow-tails).

q. Eurypylus-group. Hind wings elongate or tailed.

Genus Leptocircus.

Making, in all, twenty distinct groups of Malayan Papilionidæ.

The first section of the genus Papilio (A) comprises insects which, though differing considerably in structure, having much general resemblance. They all have a weak, low flight, frequent the most luxuriant forest-districts, seem to love the shade, and are the objects of mimicry by other Papilios.

Section B consists of weak-bodied, large-winged insects, with an irregular wavering flight, and which, when resting on foliage, often expand the wings, which the species of the other sections rarely or never do. They are the most conspicuous and striking of eastern Butterflies.

Section C consists of much weaker and slower-flying insects, often resembling in their flight, as well as in their colours, species of Danaidæ.

Section D contains the strongest-bodied and most swift-flying of the genus. They love sunlight, and frequent the borders of streams and the edges of puddles, where they gather together in swarms consisting of several species, greedily sucking up the moisture, and, when disturbed, circling round in the air, or flying high and with great strength and rapidity.

Geographical Distribution.—One hundred and thirty species of Malayan Papilionidæ are now known within the district extending from the Malay peninsula, on the north-west, to Woodlark Island, near New Guinea, on the south-east.

The exceeding richness of the Malayan region in these fine insects is seen by comparing the number of species found in the different tropical regions of the earth. From all Africa only 33 species of Papilio are known; but as several are still undescribed in collections, we may raise their number to about 40. In all tropical Asia there are at present described only 65 species, and I have seen in collections but two or three which have not yet been named. In South America, south of Panama, there are 150 species, or about one-seventh more than are yet known from the Malayan region; but the area of the two countries is very different; for while South America (even excluding Patagonia) contains 5,000,000 square miles, a line encircling the whole of the Malayan islands would only include an area of 2,700,000 square miles, of which the land-area would be about 1,000,000 square miles. This superior richness is partly real and partly apparent. The breaking up of a district into small isolated portions, as in an archipelago, seems highly favourable to the segregation and perpetuation of local peculiarities in certain groups; so that a species which on a continent might have a wide range, and whose local forms, if any, would be so connected together that it would be impossible to separate them, may become by isolation reduced to a number of such clearly defined and constant forms that we are obliged to count them as species. From this point of view, therefore, the greater proportionate number of Malayan species may be considered as apparent only. Its true superiority is shown, on the other hand, by the possession of three genera and twenty groups of Papilionidæ against a single genus and eight groups in South America, and also by the much greater average size of the Malayan species. In most other families, however, the reverse is the case, the South American Nymphalidæ, Satyridæ, and Erycinidæ far surpassing those of the East in number, variety, and beauty.

The following list, exhibiting the range and distribution of each group, will enable us to study more easily their internal and external relations.

Range of the Groups of Malayan Papilionidæ

Ornithoptera.

1. Priamus-group. Moluccas to Woodlark Island 5 species.

2. Pompeus-group. Himalayas to New Guinea, (Celebes, maximum) 11 species.

3. Brookeana-group. Sumatra and Borneo 1 species.

Papilio.

4. Nox-group. North India, Java, and Philippines 5 species

5. Coon-group. North India to Java 2 species.

6. Polydorus-group. India to New Guinea and Pacific 7 species.

7. Ulysses-group. Celebes to New Caledonia 4 species.

8. Peranthus-group. India to Timor and Moluccas (India, maximum) 9 species.

9. Memnon-group. India to Timor and Moluccas (Java, maximum) 10 species.

10. Helenus-group. Africa and India to New Guinea 11 species.

11. Pammon-group. India to Pacific and Australia 9 species.

12. Erectheus-group. Celebes to Australia 2 species.

13. Demolion-group. India to Celebes 2 species.

14. Erithonius-group. Africa, India, Australia 1 species.

15. Paradoxa-group. India to Java (Borneo, maximum) 5 species.

16. Dissimilis-group. India to Timor (India, maximum) 2 species.

17. Macareus-group. India to New Guinea 10 species.

18. Antiphates-group. Widely distributed 8 species.

19. Eurypylus-group. India to Australia 15 species.

Leptocircus.

20. Leptocircus-group. India to Celebes 4 species.

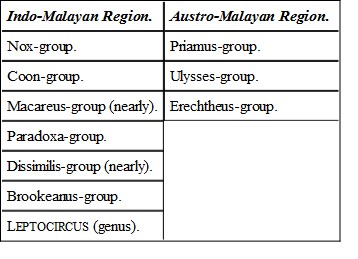

This Table shows the great affinity of the Malayan with the Indian Papilionidæ, only three out of the twenty groups ranging beyond, into Africa, Europe, or America. The limitation of groups to the Indo-Malayan or Austro-Malayan divisions of the archipelago, which is so well marked in the higher animals, is much less conspicuous in insects, but is shown in some degree by the Papilionidæ. The following groups are either almost or entirely restricted to one portion of the archipelago:—

The remaining groups, which range over the whole archipelago, are, in many cases, insects of very powerful flight, or they frequent open places and the sea-beach, and are thus more likely to get blown from island to island. The fact that three such characteristic groups as those of Priamus, Ulysses, and Erechtheus are strictly limited to the Australian region of the archipelago, while five other groups are with equal strictness confined to the Indian region, is a strong corroboration of that division which has been founded almost entirely on the distribution of Mammalia and Birds.

If the various Malayan islands have undergone recent changes of level, and if any of them have been more closely united within the period of existing species than they are now, we may expect to find indications of such changes in community of species between islands now widely separated; while those islands which have long remained isolated would have had time to acquire peculiar forms by a slow and natural process of modification.

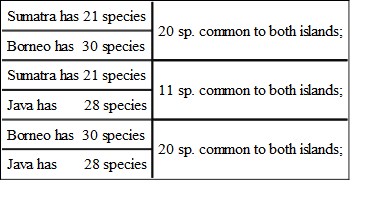

An examination of the relations of the species of the adjacent islands, will thus enable us to correct opinions formed from a mere consideration of their relative positions. For example, looking at a map of the archipelago, it is almost impossible to avoid the idea that Java and Sumatra have been recently united; their present proximity is so great, and they have such an obvious resemblance in their volcanic structure. Yet there can be little doubt that this opinion is erroneous, and that Sumatra has had a more recent and more intimate connexion with Borneo than it has had with Java. This is strikingly shown by the mammals of these islands—very few of the species of Java and Sumatra being identical, while a considerable number are common to Sumatra and Borneo. The birds show a somewhat similar relationship; and we shall find that the distribution of the Papilionidæ tells exactly the same tale. Thus:—

showing that both Sumatra and Java have a much closer relationship to Borneo than they have to each other—a most singular and interesting result, when we consider the wide separation of Borneo from them both, and its very different structure. The evidence furnished by a single group of insects would have had but little weight on a point of such magnitude if standing alone; but coming as it does to confirm deductions drawn from whole classes of the higher animals, it must be admitted to have considerable value.

We may determine in a similar manner the relations of the different Papuan Islands to New Guinea. Of thirteen species of Papilionidæ obtained in the Aru Islands, six were also found in New Guinea, and seven not. Of nine species obtained at Waigiou, six were New Guinea, and three not. The five species found at Mysol were all New Guinea species. Mysol, therefore, has closer relations to New Guinea than the other islands; and this is corroborated by the distribution of the birds, of which I will only now give one instance. The Paradise Bird found in Mysol is the common New Guinea species, while the Aru Islands and Waigiou have each a species peculiar to themselves.