полная версия

полная версияContributions to the Theory of Natural Selection

Alfred Russel Wallace

Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection / A Series of Essays

PREFACE

The present volume consists of essays which I have contributed to various periodicals, or read before scientific societies during the last fifteen years, with others now printed for the first time. The two first of the series are printed without alteration, because, having gained me the reputation of being an independent originator of the theory of “natural selection,” they may be considered to have some historical value. I have added to them one or two very short explanatory notes, and have given headings to subjects, to make them uniform with the rest of the book. The other essays have been carefully corrected, often considerably enlarged, and in some cases almost rewritten, so as to express more fully and more clearly the views which I hold at the present time; and as most of them originally appeared in publications which have a very limited circulation, I believe that the larger portion of this volume will be new to many of my friends and to most of my readers.

I now wish to say a few words on the reasons which have led me to publish this work. The second essay, especially when taken in connection with the first, contains an outline sketch of the theory of the origin of species (by means of what was afterwards termed by Mr. Darwin—“natural selection,”) as conceived by me before I had the least notion of the scope and nature of Mr. Darwin’s labours. They were published in a way not likely to attract the attention of any but working naturalists, and I feel sure that many who have heard of them, have never had the opportunity of ascertaining how much or how little they really contain. It therefore happens, that, while some writers give me more credit than I deserve, others may very naturally class me with Dr. Wells and Mr. Patrick Matthew, who, as Mr. Darwin has shown in the historical sketch given in the 4th and 5th Editions of the “Origin of Species,” certainly propounded the fundamental principle of “natural selection” before himself, but who made no further use of that principle, and failed to see its wide and immensely important applications.

The present work will, I venture to think, prove, that I both saw at the time the value and scope of the law which I had discovered, and have since been able to apply it to some purpose in a few original lines of investigation. But here my claims cease. I have felt all my life, and I still feel, the most sincere satisfaction that Mr. Darwin had been at work long before me, and that it was not left for me to attempt to write “The Origin of Species.” I have long since measured my own strength, and know well that it would be quite unequal to that task. Far abler men than myself may confess, that they have not that untiring patience in accumulating, and that wonderful skill in using, large masses of facts of the most varied kind,—that wide and accurate physiological knowledge,—that acuteness in devising and skill in carrying out experiments,—and that admirable style of composition, at once clear, persuasive and judicial,—qualities, which in their harmonious combination mark out Mr. Darwin as the man, perhaps of all men now living, best fitted for the great work he has undertaken and accomplished.

My own more limited powers have, it is true, enabled me now and then to seize on some conspicuous group of unappropriated facts, and to search out some generalization which might bring them under the reign of known law; but they are not suited to that more scientific and more laborious process of elaborate induction, which in Mr. Darwin’s hands has led to such brilliant results.

Another reason which has led me to publish this volume at the present time is, that there are some important points on which I differ from Mr. Darwin, and I wish to put my opinions on record in an easily accessible form, before the publication of his new work, (already announced,) in which I believe most of these disputed questions will be fully discussed.

I will now give the date and mode of publication of each of the essays in this volume, as well as the amount of alteration they have undergone.

I.—On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New SpeciesFirst published in the “Annals and Magazine of Natural History,” September, 1855. Reprinted without alteration of the text.

II.—On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart indefinitely from the Original TypeFirst published in the “Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnæan Society,” August, 1858. Reprinted without alteration of the text, except one or two grammatical emendations.

III.—Mimicry and other Protective Resemblances among AnimalsFirst published in the “Westminster Review,” July, 1867. Reprinted with a few corrections and some important additions, among which I may especially mention Mr. Jenner Weir’s observations and experiments on the colours of the caterpillars eaten or rejected by birds.

IV.—The Malayan Papilionidæ, Or Swallow-Tailed Butterflies, as Illustrative of the Theory of Natural SelectionFirst published in the “Transactions of the Linnæan Society,” Vol. XXV. (read March, 1864), under the title, “On the Phenomena of Variation and Geographical Distribution, as illustrated by the Papilionidæ of the Malayan Region.”

The introductory part of this essay is now reprinted, omitting tables, references to plates, &c., with some additions, and several corrections. Owing to the publication of Dr. Felder’s “Voyage of the Novara” (Lepidoptera) in the interval between the reading of my paper and its publication, several of my new species must have their names changed for those given to them by Dr. Felder, and this will explain the want of agreement in some cases between the names used in this volume and those of the original paper.

V.—On Instinct in Man and AnimalsNot previously published.

VI.—The Philosophy of Birds’ NestsFirst published in the “Intellectual Observer,” July, 1867. Reprinted with considerable emendations and additions.

VII.—A Theory of Birds’ Nests; Showing the relation of certain differences Of Colour in Birds To their mode of NidificationFirst published in the “Journal of Travel and Natural History” (No. 2), 1868. Now reprinted with considerable emendations and additions, by which I have endeavoured more clearly to express, and more fully to illustrate, my meaning in those parts which have been misunderstood by my critics.

VIII.—Creation by LawFirst published in the “Quarterly Journal of Science,” October, 1867. Now reprinted with a few alterations and additions.

IX.—The Development of Human Races under the Law of Natural SelectionFirst published in the “Anthropological Review,” May, 1864. Now reprinted with a few important alterations and additions. I had intended to have considerably extended this essay, but on attempting it I found that I should probably weaken the effect without adding much to the argument. I have therefore preferred to leave it as it was first written, with the exception of a few ill-considered passages which never fully expressed my meaning. As it now stands, I believe it contains the enunciation of an important truth.

X.—The Limits of Natural Selection as applied to ManThis is the further development of a few sentences at the end of an article on “Geological Time and the Origin of Species,” which appeared in the “Quarterly Review,” for April, 1869. I have here ventured to touch on a class of problems which are usually considered to be beyond the boundaries of science, but which, I believe, will one day be brought within her domain.

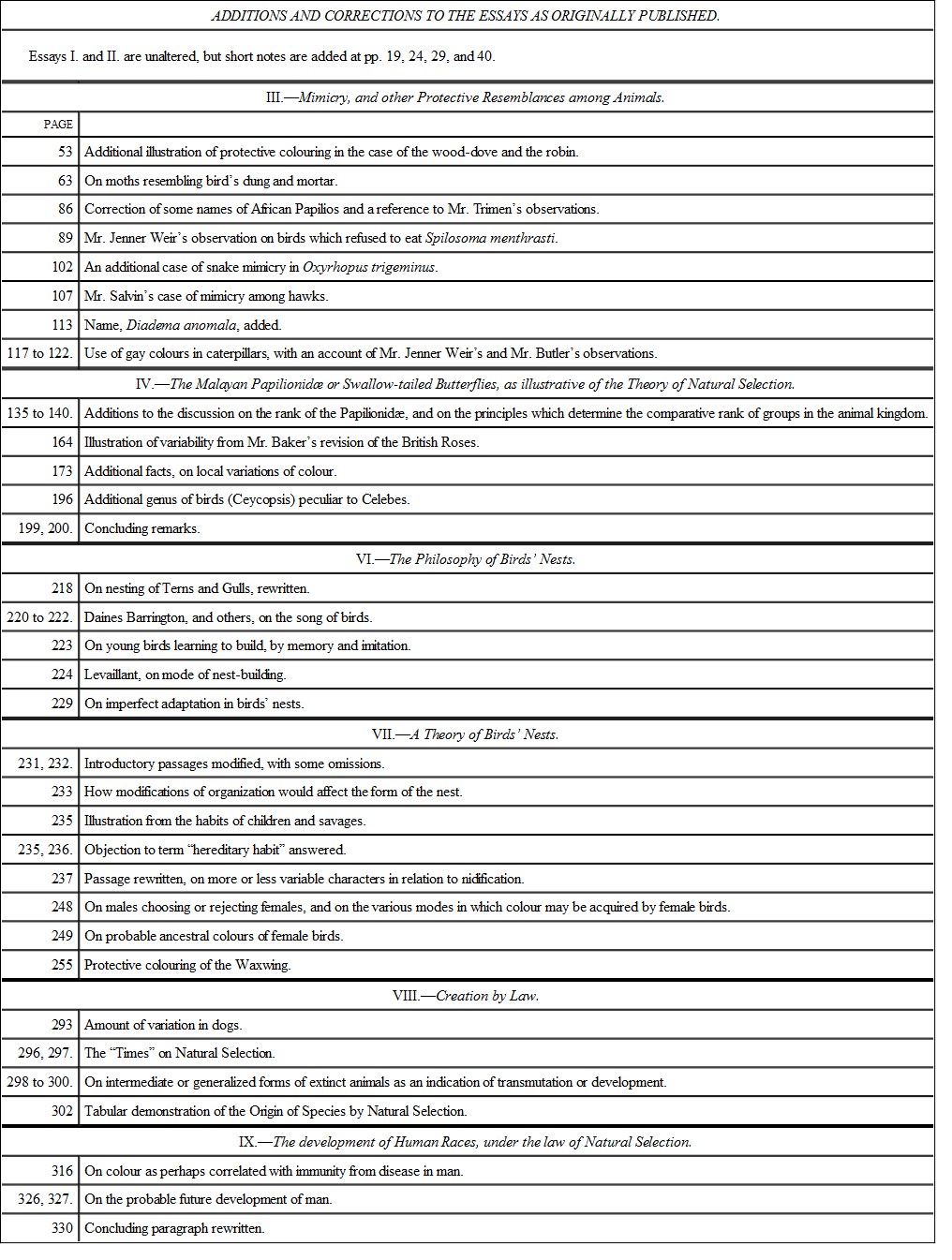

For the convenience of those who are acquainted with any of my essays in their original form, I subjoin references to the more important additions and alterations now made to them.

London, March, 1870.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

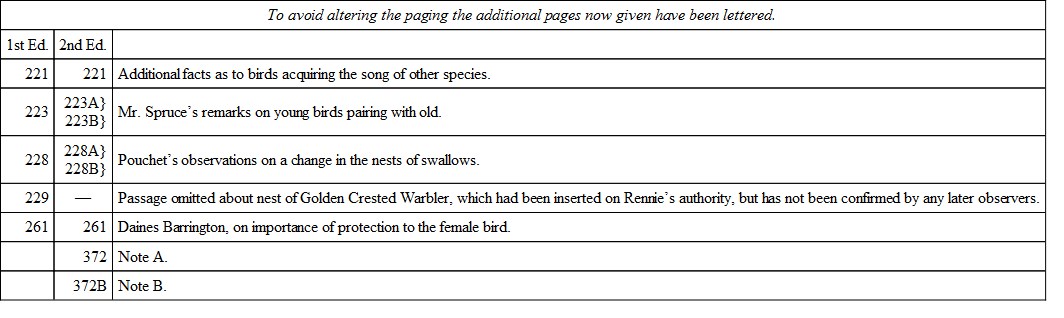

The flattering reception of my Essays by the public and the press having led to a second edition being called for within a year of its first publication, I have taken the opportunity to make a few necessary corrections. I have also added a few passages to the 6th and 7th Essays, and have given two notes, explanatory of some portions of the last chapter which appear to have been not always understood. These additions are as follows:—

I.

ON THE LAW WHICH HAS REGULATED THE INTRODUCTION OF NEW SPECIES. 1

Geographical Distribution dependent on Geologic Changes

Every naturalist who has directed his attention to the subject of the geographical distribution of animals and plants, must have been interested in the singular facts which it presents. Many of these facts are quite different from what would have been anticipated, and have hitherto been considered as highly curious, but quite inexplicable. None of the explanations attempted from the time of Linnæus are now considered at all satisfactory; none of them have given a cause sufficient to account for the facts known at the time, or comprehensive enough to include all the new facts which have since been, and are daily being added. Of late years, however, a great light has been thrown upon the subject by geological investigations, which have shown that the present state of the earth and of the organisms now inhabiting it, is but the last stage of a long and uninterrupted series of changes which it has undergone, and consequently, that to endeavour to explain and account for its present condition without any reference to those changes (as has frequently been done) must lead to very imperfect and erroneous conclusions.

The facts proved by geology are briefly these:—That during an immense, but unknown period, the surface of the earth has undergone successive changes; land has sunk beneath the ocean, while fresh land has risen up from it; mountain chains have been elevated; islands have been formed into continents, and continents submerged till they have become islands; and these changes have taken place, not once merely, but perhaps hundreds, perhaps thousands of times:—That all these operations have been more or less continuous, but unequal in their progress, and during the whole series the organic life of the earth has undergone a corresponding alteration. This alteration also has been gradual, but complete; after a certain interval not a single species existing which had lived at the commencement of the period. This complete renewal of the forms of life also appears to have occurred several times:—That from the last of the geological epochs to the present or historical epoch, the change of organic life has been gradual: the first appearance of animals now existing can in many cases be traced, their numbers gradually increasing in the more recent formations, while other species continually die out and disappear, so that the present condition of the organic world is clearly derived by a natural process of gradual extinction and creation of species from that of the latest geological periods. We may therefore safely infer a like gradation and natural sequence from one geological epoch to another.

Now, taking this as a fair statement of the results of geological inquiry, we see that the present geographical distribution of life upon the earth must be the result of all the previous changes, both of the surface of the earth itself and of its inhabitants. Many causes, no doubt, have operated of which we must ever remain in ignorance, and we may, therefore, expect to find many details very difficult of explanation, and in attempting to give one, must allow ourselves to call into our service geological changes which it is highly probable may have occurred, though we have no direct evidence of their individual operation.

The great increase of our knowledge within the last twenty years, both of the present and past history of the organic world, has accumulated a body of facts which should afford a sufficient foundation for a comprehensive law embracing and explaining them all, and giving a direction to new researches. It is about ten years since the idea of such a law suggested itself to the writer of this essay, and he has since taken every opportunity of testing it by all the newly-ascertained facts with which he has become acquainted, or has been able to observe himself. These have all served to convince him of the correctness of his hypothesis. Fully to enter into such a subject would occupy much space, and it is only in consequence of some views having been lately promulgated, he believes, in a wrong direction, that he now ventures to present his ideas to the public, with only such obvious illustrations of the arguments and results as occur to him in a place far removed from all means of reference and exact information.

A Law deduced from well-known Geographical and Geological Facts

The following propositions in Organic Geography and Geology give the main facts on which the hypothesis is founded.

Geography1. Large groups, such as classes and orders, are generally spread over the whole earth, while smaller ones, such as families and genera, are frequently confined to one portion, often to a very limited district.

2. In widely distributed families the genera are often limited in range; in widely distributed genera, well marked groups of species are peculiar to each geographical district.

3. When a group is confined to one district, and is rich in species, it is almost invariably the case that the most closely allied species are found in the same locality or in closely adjoining localities, and that therefore the natural sequence of the species by affinity is also geographical.

4. In countries of a similar climate, but separated by a wide sea or lofty mountains, the families, genera and species of the one are often represented by closely allied families, genera and species peculiar to the other.

Geology5. The distribution of the organic world in time is very similar to its present distribution in space.

6. Most of the larger and some small groups extend through several geological periods.

7. In each period, however, there are peculiar groups, found nowhere else, and extending through one or several formations.

8. Species of one genus, or genera of one family occurring in the same geological time are more closely allied than those separated in time.

9. As generally in geography no species or genus occurs in two very distant localities without being also found in intermediate places, so in geology the life of a species or genus has not been interrupted. In other words, no group or species has come into existence twice.

10. The following law may be deduced from these facts:—Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.

This law agrees with, explains and illustrates all the facts connected with the following branches of the subject:—1st. The system of natural affinities. 2nd. The distribution of animals and plants in space. 3rd. The same in time, including all the phænomena of representative groups, and those which Professor Forbes supposed to manifest polarity. 4th. The phænomena of rudimentary organs. We will briefly endeavour to show its bearing upon each of these.

The Form of a true system of Classification determined by this Law

If the law above enunciated be true, it follows that the natural series of affinities will also represent the order in which the several species came into existence, each one having had for its immediate antitype a closely allied species existing at the time of its origin. It is evidently possible that two or three distinct species may have had a common antitype, and that each of these may again have become the antitypes from which other closely allied species were created. The effect of this would be, that so long as each species has had but one new species formed on its model, the line of affinities will be simple, and may be represented by placing the several species in direct succession in a straight line. But if two or more species have been independently formed on the plan of a common antitype, then the series of affinities will be compound, and can only be represented by a forked or many branched line. Now, all attempts at a Natural classification and arrangement of organic beings show, that both these plans have obtained in creation. Sometimes the series of affinities can be well represented for a space by a direct progression from species to species or from group to group, but it is generally found impossible so to continue. There constantly occur two or more modifications of an organ or modifications of two distinct organs, leading us on to two distinct series of species, which at length differ so much from each other as to form distinct genera or families. These are the parallel series or representative groups of naturalists, and they often occur in different countries, or are found fossil in different formations. They are said to have an analogy to each other when they are so far removed from their common antitype as to differ in many important points of structure, while they still preserve a family resemblance. We thus see how difficult it is to determine in every case whether a given relation is an analogy or an affinity, for it is evident that as we go back along the parallel or divergent series, towards the common antitype, the analogy which existed between the two groups becomes an affinity. We are also made aware of the difficulty of arriving at a true classification, even in a small and perfect group;—in the actual state of nature it is almost impossible, the species being so numerous and the modifications of form and structure so varied, arising probably from the immense number of species which have served as antitypes for the existing species, and thus produced a complicated branching of the lines of affinity, as intricate as the twigs of a gnarled oak or the vascular system of the human body. Again, if we consider that we have only fragments of this vast system, the stem and main branches being represented by extinct species of which we have no knowledge, while a vast mass of limbs and boughs and minute twigs and scattered leaves is what we have to place in order, and determine the true position each originally occupied with regard to the others, the whole difficulty of the true Natural System of classification becomes apparent to us.

We shall thus find ourselves obliged to reject all these systems of classification which arrange species or groups in circles, as well as these which fix a definite number for the divisions of each group. The latter class have been very generally rejected by naturalists, as contrary to nature, notwithstanding the ability with which they have been advocated; but the circular system of affinities seems to have obtained a deeper hold, many eminent naturalists having to some extent adopted it. We have, however, never been able to find a case in which the circle has been closed by a direct and close affinity. In most cases a palpable analogy has been substituted, in others the affinity is very obscure or altogether doubtful. The complicated branching of the lines of affinities in extensive groups must also afford great facilities for giving a show of probability to any such purely artificial arrangements. Their death-blow was given by the admirable paper of the lamented Mr. Strickland, published in the “Annals of Natural History,” in which he so clearly showed the true synthetical method of discovering the Natural System.

Geographical Distribution of Organisms

If we now consider the geographical distribution of animals and plants upon the earth, we shall find all the facts beautifully in accordance with, and readily explained by, the present hypothesis. A country having species, genera, and whole families peculiar to it, will be the necessary result of its having been isolated for a long period, sufficient for many series of species to have been created on the type of pre-existing ones, which, as well as many of the earlier-formed species, have become extinct, and thus made the groups appear isolated. If in any case the antitype had an extensive range, two or more groups of species might have been formed, each varying from it in a different manner, and thus producing several representative or analogous groups. The Sylviadæ of Europe and the Sylvicolidæ of North America, the Heliconidæ of South America and the Euplœas of the East, the group of Trogons inhabiting Asia, and that peculiar to South America, are examples that may be accounted for in this manner.

Such phænomena as are exhibited by the Galapagos Islands, which contain little groups of plants and animals peculiar to themselves, but most nearly allied to those of South America, have not hitherto received any, even a conjectural explanation. The Galapagos are a volcanic group of high antiquity, and have probably never been more closely connected with the continent than they are at present. They must have been first peopled, like other newly-formed islands, by the action of winds and currents, and at a period sufficiently remote to have had the original species die out, and the modified prototypes only remain. In the same way we can account for the separate islands having each their peculiar species, either on the supposition that the same original emigration peopled the whole of the islands with the same species from which differently modified prototypes were created, or that the islands were successively peopled from each other, but that new species have been created in each on the plan of the pre-existing ones. St. Helena is a similar case of a very ancient island having obtained an entirely peculiar, though limited, flora. On the other hand, no example is known of an island which can be proved geologically to be of very recent origin (late in the Tertiary, for instance), and yet possesses generic or family groups, or even many species peculiar to itself.

When a range of mountains has attained a great elevation, and has so remained during a long geological period, the species of the two sides at and near their bases will be often very different, representative species of some genera occurring, and even whole genera being peculiar to one side only, as is remarkably seen in the case of the Andes and Rocky Mountains. A similar phænomenon occurs when an island has been separated from a continent at a very early period. The shallow sea between the Peninsula of Malacca, Java, Sumatra and Borneo was probably a continent or large island at an early epoch, and may have become submerged as the volcanic ranges of Java and Sumatra were elevated. The organic results we see in the very considerable number of species of animals common to some or all of these countries, while at the same time a number of closely allied representative species exist peculiar to each, showing that a considerable period has elapsed since their separation. The facts of geographical distribution and of geology may thus mutually explain each other in doubtful cases, should the principles here advocated be clearly established.

In all those cases in which an island has been separated from a continent, or raised by volcanic or coralline action from the sea, or in which a mountain-chain has been elevated in a recent geological epoch, the phænomena of peculiar groups or even of single representative species will not exist. Our own island is an example of this, its separation from the continent being geologically very recent, and we have consequently scarcely a species which is peculiar to it; while the Alpine range, one of the most recent mountain elevations, separates faunas and floras which scarcely differ more than may be due to climate and latitude alone.

The series of facts alluded to in Proposition (3), of closely allied species in rich groups being found geographically near each other, is most striking and important. Mr. Lovell Reeve has well exemplified it in his able and interesting paper on the Distribution of the Bulimi. It is also seen in the Humming-birds and Toucans, little groups of two or three closely allied species being often found in the same or closely adjoining districts, as we have had the good fortune of personally verifying. Fishes give evidence of a similar kind: each great river has its peculiar genera, and in more extensive genera its groups of closely allied species. But it is the same throughout Nature; every class and order of animals will contribute similar facts. Hitherto no attempt has been made to explain these singular phenomena, or to show how they have arisen. Why are the genera of Palms and of Orchids in almost every case confined to one hemisphere? Why are the closely allied species of brown-backed Trogons all found in the East, and the green-backed in the West? Why are the Macaws and the Cockatoos similarly restricted? Insects furnish a countless number of analogous examples;—the Goliathi of Africa, the Ornithopteræ of the Indian Islands, the Heliconidæ of South America, the Danaidæ of the East, and in all, the most closely allied species found in geographical proximity. The question forces itself upon every thinking mind,—why are these things so? They could not be as they are had no law regulated their creation and dispersion. The law here enunciated not merely explains, but necessitates the facts we see to exist, while the vast and long-continued geological changes of the earth readily account for the exceptions and apparent discrepancies that here and there occur. The writer’s object in putting forward his views in the present imperfect manner is to submit them to the test of other minds, and to be made aware of all the facts supposed to be inconsistent with them. As his hypothesis is one which claims acceptance solely as explaining and connecting facts which exist in nature, he expects facts alone to be brought to disprove it, not à priori arguments against its probability.