полная версия

полная версияContributions to the Theory of Natural Selection

The only other case of polymorphism in the genus Papilio, at all equal in interest to those I have now brought forward, occurs in America; and we have, fortunately, accurate information about it. Papilio Turnus is common over almost the whole of temperate North America; and the female resembles the male very closely. A totally different-looking insect both in form and colour, Papilio Glaucus, inhabits the same region; and though, down to the time when Boisduval published his “Species Général,” no connexion was supposed to exist between the two species, it is now well ascertained that P. Glaucus is a second female form of P. Turnus. In the “Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Philadelphia,” Jan., 1863, Mr. Walsh gives a very interesting account of the distribution of this species. He tells us that in the New England States and in New York all the females are yellow, while in Illinois and further south all are black; in the intermediate region both black and yellow females occur in varying proportions. Lat. 37° is approximately the southern limit of the yellow form, and 42° the northern limit of the black form; and, to render the proof complete, both black and yellow insects have been bred from a single batch of eggs. He further states that, out of thousands of specimens, he has never seen or heard of intermediate varieties between these forms. In this interesting example we see the effects of latitude in determining the proportions in which the individuals of each form should exist. The conditions are here favourable to the one form, there to the other; but we are by no means to suppose that these conditions consist in climate alone. It is highly probable that the existence of enemies, and of competing forms of life, may be the main determining influences; and it is much to be wished that such a competent observer as Mr. Walsh would endeavour to ascertain what are the adverse causes which are most efficient in keeping down the numbers of each of these contrasted forms.

Dimorphism of this kind in the animal kingdom does not seem to have any direct relations to the reproductive powers, as Mr. Darwin has shown to be the case in plants, nor does it appear to be very general. One other case only is known to me in another family of my eastern Lepidoptera, the Pieridæ; and but few occur in the Lepidoptera of other countries. The spring and autumn broods of some European species differ very remarkably; and this must be considered as a phenomenon of an analogous though not of an identical nature, while the Araschnia prorsa, of Central Europe, is a striking example of this alternate or seasonal dimorphism. Among our nocturnal Lepidoptera, I am informed, many analogous cases occur; and as the whole history of many of these has been investigated by breeding successive generations from the egg, it is to be hoped that some of our British Lepidopterists will give us a connected account of all the abnormal phenomena which they present. Among the Coleoptera Mr. Pascoe has pointed out the existence of two forms of the male sex in seven species of the two genera Xenocerus and Mecocerus belonging to the family Anthribidæ, (Proc. Ent. Soc. Lond., 1862); and no less than six European Water-beetles, of the genus Dytiscus, have females of two forms, the most common having the elytra deeply sulcate, the rarer smooth as in the males. The three, and sometimes four or more, forms under which many Hymenopterous insects (especially Ants) occur, must be considered as a related phenomenon, though here each form is specialized to a distinct function in the economy of the species. Among the higher animals, albinoism and melanism may, as I have already stated, be considered as analogous facts; and I met with one case of a bird, a species of Lory (Eos fuscata), clearly existing under two differently coloured forms, since I obtained both sexes of each from a single flock, while no intermediate specimens have yet been found.

The fact of the two sexes of one species differing very considerably is so common, that it attracted but little attention till Mr. Darwin showed how it could in many cases be explained by the principle of sexual selection. For instance, in most polygamous animals the males fight for the possession of the females, and the victors, always becoming the progenitors of the succeeding generation, impress upon their male offspring their own superior size, strength, or unusually developed offensive weapons. It is thus that we can account for the spurs and the superior strength and size of the males in Gallinaceous birds, and also for the large canine tusks in the males of fruit-eating Apes. So the superior beauty of plumage and special adornments of the males of so many birds can be explained by supposing (what there are many facts to prove) that the females prefer the most beautiful and perfect-plumaged males, and that thus, slight accidental variations of form and colour have been accumulated, till they have produced the wonderful train of the Peacock and the gorgeous plumage of the Bird of Paradise. Both these causes have no doubt acted partially in insects, so many species possessing horns and powerful jaws in the male sex only, and still more frequently the males alone rejoicing in rich colours or sparkling lustre. But there is here another cause which has led to sexual differences, viz., a special adaptation of the sexes to diverse habits or modes of life. This is well seen in female Butterflies (which are generally weaker and of slower flight), often having colours better adapted to concealment; and in certain South American species (Papilio torquatus) the females, which inhabit the forests, resemble the Æneas group of Papilios which abound in similar localities, while the males, which frequent the sunny open river-banks, have a totally different colouration. In these cases, therefore, natural selection seems to have acted independently of sexual selection; and all such cases may be considered as examples of the simplest dimorphism, since the offspring never offer intermediate varieties between the parent forms.

The phenomena of dimorphism and polymorphism may be well illustrated by supposing that a blue-eyed, flaxen-haired Saxon man had two wives, one a black-haired, red-skinned Indian squaw, the other a woolly-headed, sooty-skinned negress—and that instead of the children being mulattoes of brown or dusky tints, mingling the separate characteristics of their parents in varying degrees, all the boys should be pure Saxon boys like their father, while the girls should altogether resemble their mothers. This would be thought a sufficiently wonderful fact; yet the phenomena here brought forward as existing in the insect-world are still more extraordinary; for each mother is capable not only of producing male offspring like the father, and female like herself, but also of producing other females exactly like her fellow-wife, and altogether differing from herself. If an island could be stocked with a colony of human beings having similar physiological idiosyncrasies with Papilio Pammon or Papilio Ormenus, we should see white men living with yellow, red, and black women, and their offspring always reproducing the same types; so that at the end of many generations the men would remain pure white, and the women of the same well-marked races as at the commencement.

The distinctive character therefore of dimorphism is this, that the union of these distinct forms does not produce intermediate varieties, but reproduces the distinct forms unchanged. In simple varieties, on the other hand, as well as when distinct local forms or distinct species are crossed, the offspring never resembles either parent exactly, but is more or less intermediate between them. Dimorphism is thus seen to be a specialized result of variation, by which new physiological phenomena have been developed; the two should therefore, whenever possible, be kept separate.

3. Local form, or variety.—This is the first step in the transition from variety to species. It occurs in species of wide range, when groups of individuals have become partially isolated in several points of its area of distribution, in each of which a characteristic form has become more or less completely segregated. Such forms are very common in all parts of the world, and have often been classed by one author as varieties, by another as species. I restrict the term to those cases where the difference of the forms is very slight, or where the segregation is more or less imperfect. The best example in the present group is Papilio Agamemnon, a species which ranges over the greater part of tropical Asia, the whole of the Malay archipelago, and a portion of the Australian and Pacific regions. The modifications are principally of size and form, and, though slight, are tolerably constant in each locality. The steps, however, are so numerous and gradual that it would be impossible to define many of them, though the extreme forms are sufficiently distinct. Papilio Sarpedon presents somewhat similar but less numerous variations.

4. Co-existing Variety.—This is a somewhat doubtful case. It is when a slight but permanent and hereditary modification of form exists in company with the parent or typical form, without presenting those intermediate gradations which would constitute it a case of simple variability. It is evidently only by direct evidence of the two forms breeding separately that this can be distinguished from dimorphism. The difficulty occurs in Papilio Jason, and P. Evemon, which inhabit the same localities, and are almost exactly alike in form, size, and colouration, except that the latter always wants a very conspicuous red spot on the under surface, which is found not only in P. Jason, but in all the allied species. It is only by breeding the two insects that it can be determined whether this is a case of a co-existing variety or of dimorphism. In the former case, however, the difference being constant and so very conspicuous and easily defined, I see not how we could escape considering it as a distinct species. A true case of co-existing forms would, I consider, be produced, if a slight variety had become fixed as a local form, and afterwards been brought into contact with the parent species, with little or no intermixture of the two; and such instances do very probably occur.

5. Race or subspecies.—These are local forms completely fixed and isolated; and there is no possible test but individual opinion to determine which of them shall be considered as species and which varieties. If stability of form and “the constant transmission of some characteristic peculiarity of organization” is the test of a species (and I can find no other test that is more certain than individual opinion) then every one of these fixed races, confined as they almost always are to distinct and limited areas, must be regarded as a species; and as such I have in most cases treated them. The various modifications of Papilio Ulysses, P. Peranthus, P. Codrus, P. Eurypilus, P. Helenus, &c., are excellent examples; for while some present great and well-marked, others offer slight and inconspicuous differences, yet in all cases these differences seem equally fixed and permanent. If, therefore, we call some of these forms species, and others varieties, we introduce a purely arbitrary distinction, and shall never be able to decide where to draw the line. The races of Papilio Ulysses, for example, vary in amount of modification from the scarcely differing New Guinea form to those of Woodlark Island and New Caledonia, but all seem equally constant; and as most of these had already been named and described as species, I have added the New Guinea form under the name of P. Autolycus. We thus get a little group of Ulyssine Papilios, the whole comprised within a very limited area, each one confined to a separate portion of that area, and, though differing in various amounts, each apparently constant. Few naturalists will doubt that all these may and probably have been derived from a common stock, and therefore it seems desirable that there should be a unity in our method of treating them; either call them all varieties or all species. Varieties, however, continually get overlooked; in lists of species they are often altogether unrecorded; and thus we are in danger of neglecting the interesting phenomena of variation and distribution which they present. I think it advisable, therefore, to name all such forms; and those who will not accept them as species may consider them as subspecies or races.

Variation as specially influenced by Locality

The phenomena of variation as influenced by locality have not hitherto received much attention. Botanists, it is true, are acquainted with the influences of climate, altitude, and other physical conditions, in modifying the forms and external characteristics of plants; but I am not aware that any peculiar influence has been traced to locality, independent of climate. Almost the only case I can find recorded is mentioned in that repertory of natural-history facts, “The Origin of Species,” viz. that herbaceous groups have a tendency to become arboreal in islands. In the animal world, I cannot find that any facts have been pointed out as showing the special influence of locality in giving a peculiar facies to the several disconnected species that inhabit it. What I have to adduce on this matter will therefore, I hope, possess some interest and novelty.

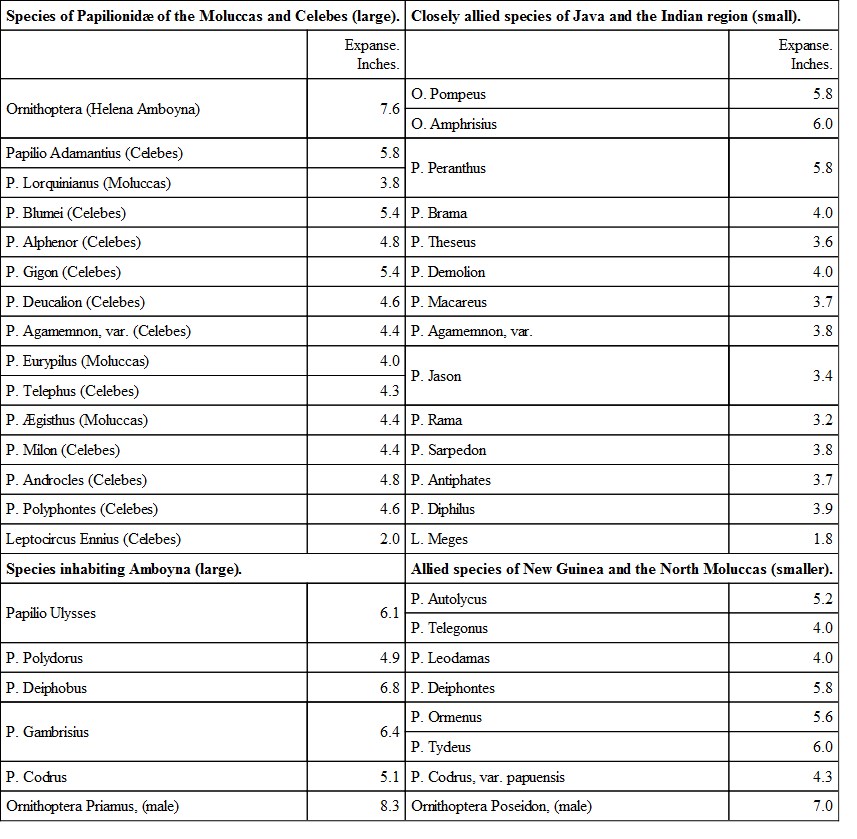

On examining the closely allied species, local forms, and varieties distributed over the Indian and Malayan regions, I find that larger or smaller districts, or even single islands, give a special character to the majority of their Papilionidæ. For instance: 1. The species of the Indian region (Sumatra, Java, and Borneo) are almost invariably smaller than the allied species inhabiting Celebes and the Moluccas; 2. The species of New Guinea and Australia are also, though in a less degree, smaller than the nearest species or varieties of the Moluccas; 3. In the Moluccas themselves the species of Amboyna are the largest; 4. The species of Celebes equal or even surpass in size those of Amboyna; 5. The species and varieties of Celebes possess a striking character in the form of the anterior wings, different from that of the allied species and varieties of all the surrounding islands; 6. Tailed species in India or the Indian region become tailless as they spread eastward through the archipelago; 7. In Amboyna and Ceram the females of several species are dull-coloured, while in the adjacent islands they are more brilliant.

Local variation of Size.—Having preserved the finest and largest specimens of Butterflies in my own collection, and having always taken for comparison the largest specimens of the same sex, I believe that the tables I now give are sufficiently exact. The differences of expanse of wings are in most cases very great, and are much more conspicuous in the specimens themselves than on paper. It will be seen that no less than fourteen Papilionidæ inhabiting Celebes and the Moluccas are from one-third to one-half greater in extent of wing than the allied species representing them in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo. Six species inhabiting Amboyna are larger than the closely allied forms of the northern Moluccas and New Guinea by about one-sixth. These include almost every case in which closely allied species can be compared.

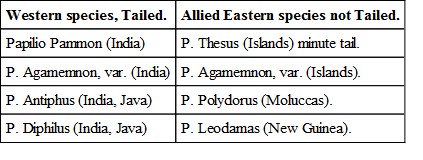

Local variation of Form.—The differences of form are equally clear. Papilio Pammon everywhere on the continent is tailed in both sexes. In Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, the closely allied P. Theseus has a very short tail, or tooth only, in the male, while in the females the tail is retained. Further east, in Celebes and the South Moluccas, the hardly separable P. Alphenor has quite lost the tail in the male, while the female retains it, but in a narrower and less spatulate form. A little further, in Gilolo, P. Nicanor has completely lost the tail in both sexes.

Papilio Agamemnon exhibits a somewhat similar series of changes. In India it is always tailed; in the greater part of the archipelago it has a very short tail; while far east, in New Guinea and the adjacent islands, the tail has almost entirely disappeared.

In the Polydorus-group two species, P. Antiphus and P. Diphilus, inhabiting India and the Indian region, are tailed, while the two which take their place in the Moluccas, New Guinea, and Australia, P. Polydorus and P. Leodamas, are destitute of tail, the species furthest east having lost this ornament the most completely.

The most conspicuous instance of local modification of form, however, is exhibited in the island of Celebes, which in this respect, as in some others, stands alone and isolated in the whole archipelago. Almost every species of Papilio inhabiting Celebes has the wings of a peculiar shape, which distinguishes them at a glance from the allied species of every other island. This peculiarity consists, first, in the upper wings being generally more elongate and falcate; and secondly, in the costa or anterior margin being much more curved, and in most instances exhibiting near the base an abrupt bend or elbow, which in some species is very conspicuous. This peculiarity is visible, not only when the Celebesian species are compared with their small-sized allies of Java and Borneo, but also, and in an almost equal degree, when the large forms of Amboyna and the Moluccas are the objects of comparison, showing that this is quite a distinct phenomenon from the difference of size which has just been pointed out.

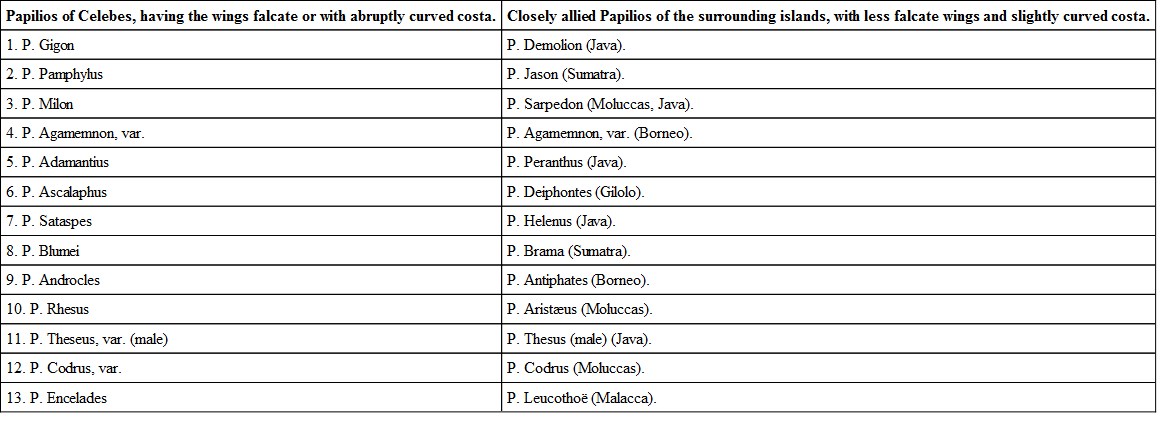

In the following Table I have arranged the chief Papilios of Celebes in the order in which they exhibit this characteristic form most prominently.

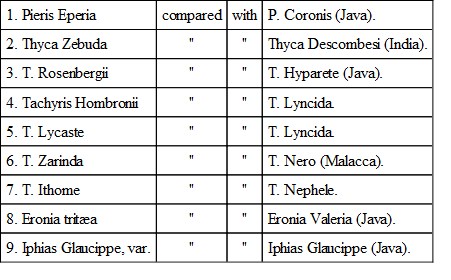

It thus appears that every species of Papilio exhibits this peculiar form in a greater or less degree, except one, P. Polyphontes, allied to P. Diphilus of India and P. Polydorus of the Moluccas. This fact I shall recur to again, as I think it helps us to understand something of the causes that may have brought about the phenomenon we are considering. Neither do the genera Ornithoptera and Leptocircus exhibit any traces of this peculiar form. In several other families of Butterflies this characteristic form reappears in a few species. In the Pieridæ the following species, all peculiar to Celebes, exhibit it distinctly:—

The species of Terias, one or two Pieris, and the genus Callidryas do not exhibit any perceptible change of form.

In the other families there are but few similar examples. The following are all that I can find in my collection:—

All these belong to the family of the Nymphalidæ. Many other genera of this family, as Diadema, Adolias, Charaxes, and Cyrestis, as well as the entire families of the Danaidæ, Satyridæ, Lycænidæ, and Hesperidæ, present no examples of this peculiar form of the upper wing in the Celebesian species.

Local variations of Colour.—In Amboyna and Ceram the female of the large and handsome Ornithoptera Helena has the large patch on the hind wings constantly of a pale dull ochre or buff colour, while in the scarcely distinguishable varieties from the adjacent islands of Bouru and New Guinea, it is of a golden yellow, hardly inferior in brilliancy to its colour in the male sex. The female of Ornithoptera Priamus (inhabiting Amboyna and Ceram exclusively) is of a pale dusky brown tint, while in all the allied species the same sex is nearly black with contrasted white markings. As a third example, the female of Papilio Ulysses has the blue colour obscured by dull and dusky tints, while in the closely allied species from the surrounding islands, the females are of almost as brilliant an azure blue as the males. A parallel case to this is the occurrence, in the small islands of Goram, Matabello, Ké, and Aru, of several distinct species of Euplœa and Diadema, having broad bands or patches of white, which do not exist in any of the allied species from the larger islands. These facts seem to indicate some local influence in modifying colour, as unintelligible and almost as remarkable as that which has resulted in the modifications of form previously described.

Remarks on the facts of Local variation

The facts now brought forward seem to me of the highest interest. We see that almost all the species in two important families of the Lepidoptera (Papilionidæ and Pieridæ) acquire, in a single island, a characteristic modification of form distinguishing them from the allied species and varieties of all the surrounding islands. In other equally extensive families no such change occurs, except in one or two isolated species. However we may account for these phenomena, or whether we may be quite unable to account for them, they furnish, in my opinion, a strong corroborative testimony in favour of the doctrine of the origin of species by successive small variations; for we have here slight varieties, local races, and undoubted species, all modified in exactly the same manner, indicating plainly a common cause producing identical results. On the generally received theory of the original distinctness and permanence of species, we are met by this difficulty: one portion of these curiously modified forms are admitted to have been produced by variation and some natural action of local conditions; whilst the other portion, differing from the former only in degree, and connected with them by insensible gradations, are said to have possessed this peculiarity of form at their first creation, or to have derived it from unknown causes of a totally distinct nature. Is not the à priori evidence in favour of an identity of the causes that have produced such similar results? and have we not a right to call upon our opponents for some proofs of their own doctrine, and for an explanation of its difficulties, instead of their assuming that they are right, and laying upon us the burthen of disproof?

Let us now see if the facts in question do not themselves furnish some clue to their explanation. Mr. Bates has shown that certain groups of butterflies have a defence against insectivorous animals, independent of swiftness of motion. These are generally very abundant, slow, and weak fliers, and are more or less the objects of mimicry by other groups, which thus gain an advantage in a freedom from persecution similar to that enjoyed by those they resemble. Now the only Papilios which have not in Celebes acquired the peculiar form of wing, belong to a group which is imitated both by other species of Papilio and by Moths of the genus Epicopeia. This group is of weak and slow flight; and we may therefore fairly conclude that it possesses some means of defence (probably in a peculiar odour or taste) which saves it from attack. Now the arched costa and falcate form of wing is generally supposed to give increased powers of flight, or, as seems to me more probable, greater facility in making sudden turnings, and thus baffling a pursuer. But the members of the Polydorus-group (to which belongs the only unchanged Celebesian Papilio), being already guarded against attack, have no need of this increased power of wing; and “natural selection” would therefore have no tendency to produce it. The whole family of Danaidæ are in the same position: they are slow and weak fliers; yet they abound in species and individuals, and are the objects of mimicry. The Satyridæ have also probably a means of protection—perhaps their keeping always near the ground and their generally obscure colours; while the Lycænidæ and Hesperidæ may find security in their small size and rapid motions. In the extensive family of the Nymphalidæ, however, we find that several of the larger species, of comparatively feeble structure, have their wings modified (Cethosia, Limenitis, Junonia, Cynthia), while the large-bodied powerful species, which have all an excessively rapid flight, have exactly the same form of wing in Celebes as in the other islands. On the whole, therefore, we may say that all the butterflies of rather large size, conspicuous colours, and not very swift flight have been affected in the manner described, while the smaller sized and obscure groups, as well as those which are the objects of mimicry, and also those of exceedingly swift flight have remained unaffected.