полная версия

полная версияLogic: Deductive and Inductive

To avoid certain misunderstandings, some slight alterations have been made in the wording of the Canons. It may seem questionable whether the Canons add anything to the above propositions: I think they do. They are not discussed in the ensuing chapter merely out of reverence for Mill, or regard for a nascent tradition; but because, as describing the character of observations and experiments that justify us in drawing conclusions about causation, they are guides to the analysis of observations and to the preparation of experiments. To many eminent investigators the Canons (as such) have been unknown; but they prepared their work effectively so far only as they had definite ideas to the same purport. A definite conception of the conditions of proof is the necessary antecedent of whatever preparations may be made for proving anything.

CHAPTER XVI

THE CANONS OF DIRECT INDUCTION

§ 1. Let me begin by borrowing an example from Bain (Logic: B. III. c. 6). The North-East wind is generally detested in this country: as long as it blows few people feel at their best. Occasional well-known causes of a wind being injurious are violence, excessive heat or cold, excessive dryness or moisture, electrical condition, the being laden with dust or exhalations. Let the hypothesis be that the last is the cause of the North-East wind's unwholesome quality; since we know it is a ground current setting from the pole toward the equator and bent westward by the rotation of the earth; so that, reaching us over thousands of miles of land, it may well be fraught with dust, effluvia, and microbes. Now, examining many cases of North-East wind, we find that this is the only circumstance in which all the instances agree: for it is sometimes cold, sometimes hot; generally dry, but sometimes wet; sometimes light, sometimes violent, and of all electrical conditions. Each of the other circumstances, then, can be omitted without the N.E. wind ceasing to be noxious; but one circumstance is never absent, namely, that it is a ground current. That circumstance, therefore, is probably the cause of its injuriousness. This case illustrates:—

(I) The Canon of AgreementIf two or more instances of a phenomenon under investigation have only one other circumstance (antecedent or consequent) in common, that circumstance is probably the cause (or an indispensable condition) or the effect of the phenomenon, or is connected with it by causation.

This rule of proof (so far as it is used to establish direct causation) depends, first, upon observation of an invariable connection between the given phenomenon and one other circumstance; and, secondly, upon I. (a) and II. (b) among the propositions obtained from the unconditionality of causation at the close of the last chapter.

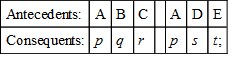

To prove that A is causally related to p, suppose two instances of the occurrence of A, an antecedent, and p, a consequent, with concomitant facts or events—and let us represent them thus:

and suppose further that, in this case, the immediate succession of events can be observed. Then A is probably the cause, or an indispensable condition, of p. For, as far as our instances go, A is the invariable antecedent of p; and p is the invariable consequent of A. But the two instances of A or p agree in no other circumstance. Therefore A is (or completes) the unconditional antecedent of p. For B and C are not indispensable conditions of p, being absent in the second instance (Rule II. (b)); nor are D and E, being absent in the first instance. Moreover, q and r are not effects of A, being absent in the second instance (Rule II. (d)); nor are s and t, being absent in the first instance.

It should be observed that the cogency of the proof depends entirely upon its tending to show the unconditionality of the sequence A-p, or the indispensability of A as a condition of p. That p follows A, even immediately, is nothing by itself: if a man sits down to study and, on the instant, a hand-organ begins under his window, he must not infer malice in the musician: thousands of things follow one another every moment without traceable connection; and this we call 'accidental.' Even invariable sequence is not enough to prove direct causation; for, in our experience does not night invariable follow day? The proof requires that the instances be such as to show not merely what events are in invariable sequence, but also what are not. From among the occasional antecedents of p (or consequents of A) we have to eliminate the accidental ones. And this is done by finding or making 'negative instances' in respect of each of them. Thus the instance

is a negative instance of B and C considered as supposable causes of p (and of q and r as supposable effects of A); for it shows that they are absent when p (or A) is present.

To insist upon the cogency of 'negative instances' was Bacon's great contribution to Inductive Logic. If we neglect them, and merely collect examples of the sequence A-p, this is 'simple enumeration'; and although simple enumeration, when the instances of agreement are numerous enough, may give rise to a strong belief in the connection of phenomena, yet it can never be a methodical or logical proof of causation, since it does not indicate the unconditionalness of the sequence. For simple enumeration of the sequence A-p leaves open the possibility that, besides A, there is always some other antecedent of p, say X; and then X may be the cause of p. To disprove it, we must find, or make, a negative instance of X—where p occurs, but X is absent.

So far as we recognise the possibility of a plurality of causes, this method of Agreement cannot be quite satisfactory. For then, in such instances as the above, although D is absent in the first, and B in the second, it does not follow that they are not the causes of p; for they may be alternative causes: B may have produced p in the first instance, and D in the second; A being in both cases an accidental circumstance in relation to p. To remedy this shortcoming by the method of Agreement itself, the only course is to find more instances of p. We may never find a negative instance of A; and, if not, the probability that A is the cause of p increases with the number of instances. But if there be no antecedent that we cannot sometimes exclude, yet the collection of instances will probably give at last all the causes of p; and by finding the proportion of instances in which A, B, or X precedes p, we may estimate the probability of any one of them being the cause of p in any given case of its occurrence.

But this is not enough. Since there cannot really be vicarious causes, we must define the effect (p) more strictly, and examine the cases to find whether there may not be varieties of p, with each of which one of the apparent causes is correlated: A with p1 B with p11, X with p111. Or, again, it may be that none of the recognised antecedents is effective: as we here depend solely on observation, the true conditions may be so recondite and disguised by other phenomena as to have escaped our scrutiny. This may happen even when we suppose that the chief condition has been isolated: the drinking of foul water was long believed to cause dysentery, because it was a frequent antecedent; whilst observation had overlooked the bacillus, which was the indispensable condition.

Again, though we have assumed that, in the instances supposed above, immediate sequence is observable, yet in many cases it may not be so, if we rely only on the canon of Agreement; if instances cannot be obtained by experiment, and we have to depend on observation. The phenomena may then be so mixed together that A and p seem to be merely concomitant; so that, though connection of some sort may be rendered highly probable, we may not be able to say which is cause and which is effect. We must then try (as Bain says) to trace the expenditure of energy: if p gains when A loses, the course of events if from A to p.

Moreover, where succession cannot be traced, the method of Agreement may point to a connection between two or more facts (perhaps as co-effects of a remote cause) where direct causation seems to be out of the question: e.g., that Negroes, though of different tribes, different localities, customs, etc., are prognathous, woolly-haired and dolichocephalic.

The Method of Agreement, then, cannot by itself prove causation. Its chief use (as Mill says) is to suggest hypotheses as to the cause; which must then be used (if possible) experimentally to try if it produces the given effect. A bacillus, for example, being always found with a certain disease, is probably the chief condition of it: give it to a guinea-pig, and observe whether the disease appears in that animal.

Men often use arguments which, if they knew it, might be shown to conform more or less to this canon; for they collect many instances to show that two events are connected; but usually neglect to bring out the negative side of the proof; so that their arguments only amount to simple enumeration. Thus Ascham in his Toxophilus, insisting on the national importance of archery, argues that victory has always depended on superiority in shooting; and, to prove it, he shows how the Parthians checked the Romans, Sesostris conquered a great part of the known world, Tiberius overcame Arminius, the Turks established their empire, and the English defeated the French (with many like examples)—all by superior archery. But having cited these cases to his purpose, he is content; whereas he might have greatly strengthened his proof by showing how one or the other instance excludes other possible causes of success. Thus: the cause was not discipline, for the Romans were better disciplined than the Parthians; nor yet the boasted superiority of a northern habitat, for Sesostris issued from the south; nor better manhood, for here the Germans probably had the advantage of the Romans; nor superior civilisation, for the Turks were less civilised than most of those they conquered; nor numbers, nor even a good cause, for the French were more numerous than the English, and were shamefully attacked by Henry V. on their own soil. Many an argument from simple enumeration may thus be turned into an induction of greater plausibility according to the Canon of Agreement.

Still, in the above case, the effect (victory) is so vaguely conceived, that a plurality of causes must be allowed for: although, e.g., discipline did not enable the Romans to conquer the Parthians, it may have been their chief advantage over the Germans; and it was certainly important to the English under Henry V. in their war with the French.

Here is another argument, somewhat similar to the above, put forward by H. Spencer with a full consciousness of its logical character. States that make war their chief object, he says, assume a certain type of organisation, involving the growth of the warrior class and the treatment of labourers as existing solely to sustain the warriors; the complete subordination of individuals to the will of the despotic soldier-king, their property, liberty and life being at the service of the State; the regimentation of society not only for military but also for civil purposes; the suppression of all private associations, etc. This is the case in Dahomey and in Russia, and it was so at Sparta, in Egypt, and in the empire of the Yncas. But the similarity of organisation in these States cannot have been due to race, for they are all of different races; nor to size, for some are small, some large; nor to climate or other circumstances of habitat, for here again they differ widely: the one thing they have in common is the military purpose; and this, therefore, must be the cause of their similar organisation. (Political Institutions.)

By this method, then, to prove that one thing is causally connected with another, say A with p, we show, first, that in all instances of p, A is present; and, secondly, that any other supposable cause of p may be absent without disturbing p. We next come to a method the use of which greatly strengthens the foregoing, by showing that where p is absent A is also absent, and (if possible) that A is the only supposable cause that is always absent along with p.

§ 2. The Canon of the Joint Method of Agreement in Presence and in Absence.

If (1) two or more instances in which a phenomenon occurs have only one other circumstance (antecedent or consequent) in common, while (2) two or more instances in which it does not occur (though in important points they resemble the former set of instances) have nothing else in common save the absence of that circumstance—the circumstance in which alone the two sets of instances differ throughout (being present in the first set and absent in the second) is probably the effect, or the cause, or an indispensable condition of the phenomenon.

The first clause of this Canon is the same as that of the method of Agreement, and its significance depends upon the same propositions concerning causation. The second clause, relating to instances in which the phenomenon is absent, depends for its probative force upon Prop. II. (a), and I. (b): its function is to exclude certain circumstances (whose nature or manner of occurrence gives them some claim to consideration) from the list of possible causes (or effects) of the phenomenon investigated. It might have been better to state this second clause separately as the Canon of the Method of Exclusions.

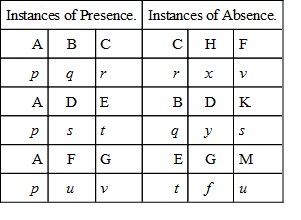

To prove that A is causally related to p, let the two sets of instances be represented as follows:

Then A is probably the cause or a condition of p, or p is dependent upon A: first, by the Canon of Agreement in Presence, as represented by the first set of instances; and, secondly, by Agreement in Absence in the second set of instances. For there we see that C, H, F, B, D, K, E, G, M occur without the phenomenon p, and therefore (by Prop. II. (a)) are not its cause, or not the whole cause, unless they have been counteracted (which is a point for further investigation). We also see that r, v, q, s, t, u occur without A, and therefore are not the effects of A. And, further, if the negative instances represent all possible cases, we see that (according to Prop. I. (b)) A is the cause of p, because it cannot be omitted without the cessation of p. The inference that A and p are cause and effect, suggested by their being present throughout the first set of instances, is therefore strengthened by their being both absent throughout the second set.

So far as this Double Method, like the Single Method of Agreement, relies on observation, sequence may not be perceptible in the instances observed, and then, direct causation cannot be proved by it, but only the probability of causal connection; and, again, the real cause, though present, may be so obscure as to evade observation. It has, however, one peculiar advantage, namely, that if the second list of instances (in which the phenomenon and its supposed antecedent are both absent) can be made exhaustive, it precludes any hypothesis of a plurality of causes; since all possible antecedents will have been included in this list without producing the phenomenon. Thus, in the above symbolic example, taking the first set of instances, the supposition is left open that B, C, D, E, F, G may, at one time or another, have been a condition of p; but, in the second list, these antecedents all occur, here or there, without producing p, and therefore (unless counteracted somehow) cannot be a condition of p. A, then, stands out as the one thing that is present whenever p is present, and absent whenever p is absent.

Stated in this abstract way, the Double Method may seem very elaborate and difficult; yet, in fact, its use may be very simple. Tyndall, to prove that dispersed light in the air is due to motes, showed by a number of cases (1) that any gas containing motes is luminous; (2) that air in which the motes had been destroyed by heat, and any gas so prepared as to exclude motes, are not luminous. All the instances are of gases, and the result is: motes—luminosity; no motes—no luminosity. Darwin, to show that cross-fertilisation is favourable to flowers, placed a net about 100 flower-heads, and left 100 others of the same varieties exposed to the bees: the former bore no seed, the latter nearly 3,000. We must assume that, in Darwin's judgment, the net did not screen the flowers from light and heat sufficiently to affect the result.

There are instructive applications of this Double Method in Wallace's Darwinism. In chap. viii., on Colour in Animals, he observes, that the usefulness of their coloration to animals is shown by the fact that, "as a rule, colour and marking are constant in each species of wild animal, while, in almost every domesticated animal, there arises great variability. We see this in our horses and cattle, our dogs and cats, our pigeons and poultry. Now the essential difference between the conditions of life of domesticated and wild animals is, that the former are protected by man, while the latter have to protect themselves." Wild animals protect themselves by acquiring qualities adapted to their mode of life; and coloration is a very important one, its chief, though not its only use, being concealment. Hence a useful coloration having been established in any species, individuals that occasionally may vary from it, will generally, perish; whilst, among domestic animals, variation of colour or marking is subject to no check except the taste of owners. We have, then, two lists of instances; first, innumerable species of wild animals in which the coloration is constant and which depend upon their own qualities for existence; secondly, several species of domestic animals in which the coloration is not constant, and which do not depend upon their own qualities for existence. In the former list two circumstances are present together (under all sorts of conditions); in the latter they are absent together. The argument may be further strengthened by adding a third list, parallel to the first, comprising domestic animals in which coloration is approximately constant, but where (as we know) it is made a condition of existence by owners, who only breed from those specimens that come up to a certain standard of coloration.

Wallace goes on to discuss the colouring of arctic animals. In the arctic regions, he says, some animals are wholly white all the year round, such as the polar bear, the American polar hare, the snowy owl and the Greenland falcon: these live amidst almost perpetual snow. Others, that live where the snow melts in summer, only turn white in winter, such as the arctic hare, the arctic fox, the ermine and the ptarmigan. In all these cases the white colouring is useful, concealing the herbivores from their enemies, and also the carnivores in approaching their prey; this usefulness, therefore, is a condition of the white colouring. Two other explanations have, however, been suggested: first, that the prevalent white of the arctic regions directly colours the animals, either by some photographic or chemical action on the skin, or by a reflex action through vision (as in the chameleon); secondly, that a white skin checks radiation and keeps the animals warm. But there are some exceptions to the rule of white colouring in arctic animals which refute these hypotheses, and confirm the author's. The sable remains brown throughout the winter; but it frequents trees, with whose bark its colour assimilates. The musk-sheep is brown and conspicuous; but it is gregarious, and its safety depends upon its ability to recognise its kind and keep with the herd. The raven is always black; but it fears no enemy and feeds on carrion, and therefore does not need concealment for either defence or attack. The colour of the sable, then, though not white, serves for concealment; the colour of the musk-sheep serves a purpose more important than concealment; the raven needs no concealment. There are thus two sets of instances:—in one set the animals are white (a) all the year, (b) in winter; and white conceals them (a) all the year, (b) in winter; in the other set, the animals are not white, and to them either whiteness would not give concealment, or concealment would not be advantageous. And this second list refutes the rival hypotheses: for the sable, the musk-sheep and the raven are as much exposed to the glare of the snow, and to the cold, as the other animals are.

§ 3. The Canon of Difference.

If an instance in which a phenomenon occurs, and an instance in which it does not occur, have every other circumstance in common save one, that one (whether consequent or antecedent) occurring only in the former; the circumstance in which alone the two instances differ is the effect, or the cause, or an indispensable condition of the phenomenon.

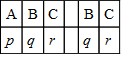

This follows from Props. I (a) and (b), in chapter xv. § 7. To prove that A is a condition of p, let two instances, such as the Canon requires, be represented thus:

Then A is the cause or a condition of p. For, in the first instance, A being introduced (without further change), p arises (Prop. I. (a)); and, in the second instance, A having been removed (without other change), p disappears (Prop. I. (b)). Similarly we may prove, by the same instances, that p is the effect of A.

The order of the phenomena and the immediacy of their connection is a matter for observation, aided by whatever instruments and methods of inspection and measurement may be available.

As to the invariability of the connection, it may of course be tested by collecting more instances or making more experiments; but it has been maintained, that a single perfect experiment according to this method is sufficient to prove causation, and therefore implies invariability (since causation is uniform), though no other instances should ever be obtainable; because it establishes once for all the unconditionality of the connection

Now, formally this is true; but in any actual investigation how shall we decide what is a satisfactory or perfect experiment? Such an experiment requires that in the negative instance

BC shall be the least assemblage of conditions necessary to co-operate with A in producing p; and that it is so cannot be ascertained without either general prior knowledge of the nature of the case or special experiments for the purpose. So that invariability will not really be inferred from a single experiment; besides that every prudent inquirer repeats his experiments, if only to guard against his own liability to error.

The supposed plurality of causes does not affect the method of Difference. In the above symbolic case, A is clearly one cause (or condition) of p, whatever other causes may be possible; whereas with the Single Method of Agreement, it remained doubtful (admitting a plurality of causes) whether A, in spite of being always present with p, was ever a cause or condition of it.

This method of Difference without our being distinctly aware of it, is oftener than any other the basis of ordinary judgments. That the sun gives light and heat, that food nourishes and fire burns, that a stone breaks a window or kills a bird, that the turning of a tap permits or checks the flow of water or of gas, and thousands of other propositions are known to be true by rough but often emphatic applications of this method in common experience.