полная версия

полная версияDiary in America, Series One

During my sojourn in the United States I became acquainted with a large portion of the senior officers of the American navy, and I found them gifted, gentleman-like, and liberal. With them I could converse freely upon all points relative to the last war, and always found them ready to admit all that could be expected. The American naval officers certainly form a strong contrast to the majority of their countrymen, and prove, by their enlightened and liberal ideas, how much the Americans, in general, would be improved if they enjoyed the same means of comparison with other countries which the naval officers, by their profession, have obtained. Their partial successes during the late war were often the theme of discourse, which was conducted with candour and frankness on both sides. No unpleasant feeling was ever excited by any argument with them on the subject, whilst the question, raised amongst their “free and enlightened” brother citizens, who knew nothing of the matter, was certain to bring down upon me such a torrent of bombast, falsehood, and ignorance, as required all my philosophy to submit to with apparent indifference. But I must now take my leave of the American navy, and notice their merchant marine.

Before I went to the United States I was aware that a large proportion of our seamen were in their employ. I knew that the whole line of packets, which is very extensive, was manned by British seamen; but it was not until I arrived in the states that I discovered the real state of the case.

During my occasional residence at New York, I was surprised to find myself so constantly called upon by English seamen, who had served under me in the different ships I had commanded since the peace. Every day seven or eight would come, touch their hats, and remind me in what ships, and in what capacity, they had done their duty. I had frequent conversations with them, and soon discovered that their own expression, “We are all here, sir,” was strictly true. To the why and the wherefore, the answer was invariably the same. “Eighteen dollars a-month, sir.” Some of them, I recollect, told me that they were going down to New Orleans, because the sickly season was coming on; and that during the time the yellow fever raged they always had a great advance of wages, receiving sometimes as much as thirty dollars per month. I did not attempt to dissuade them from their purpose; they were just as right to risk their lives from contagion at thirty dollars a-month, as to stand and be fired at a shilling a day. The circumstance of so many of my own men being in American ships, and their assertion that there were no other sailors than English at New York, induced me to enter very minutely into my investigation, of which the following are the results:—

The United States, correctly speaking, have no common seamen, or seamen bred up as apprentices before the mast. Indeed a little reflection will show how unlikely it is that they ever should have; for who would submit to such a dog’s life (as at the best it is), or what parent would consent that his children should wear out an existence of hardship and dependence at sea, when he could so easily render them independent on shore? The same period of time requisite for a man to learn his duty ay an able seaman, and be qualified for the pittance of eighteen dollars per month, would be sufficient to establish a young man as an independent, or even wealthy, land-owner, factor, or merchant. That there are classes in America who do go to sea is certain, and who and what these are I shall hereafter point out; but it may be positively asserted that, unless by escaping from their parents at an early age, and before their education is complete, they become, as it were, lost, there is in the United States of America hardly an instance of a white boy being sent to sea, to be brought up as a foremast man.

It may be here observed that there is a wide difference in the appearance of an English seaman and a portion of those styling themselves American seamen, who are to be seen at Liverpool and other seaports; tall, weedy, narrow-shouldered, slovenly, yet still athletic men, with their knives worn in a sheath outside of their clothes, and not with a lanyard round them, as is the usual custom of English seamen. There is, I grant, a great difference in their appearance, and it arises from the circumstance of those men having been continually in the trade to New Orleans and the South, where they have picked up the buccaneer airs and customs which are still in existence there; but the fact is, that, though altered also by climate, the majority of them were Englishmen born, who served their first apprenticeship in the coasting trade, but left it at an early age for America. They may be considered as a portion of the emigrants to America, having become in feeling, as well as in other respects, bona fide Americans.

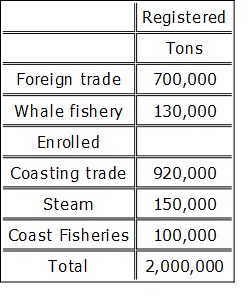

The whole amount of tonnage of the American mercantile manner may be taken, in round numbers, at 2,000,000 tons, which may be subdivided as follows:

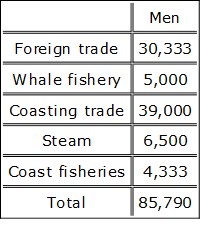

The American merchant vessels are generally sailed with fewer men than the British calculate five men to one hundred tons, which I believe to be about the just proportion. Mr Carey, in his work, estimates the proportion of seamen in American vessels to be 44 to every one hundred tons, and I shall assume his calculation as correct. The number of men employed in the American mercantile navy will be as follows:—

And now I will submit, from the examinations I have made, the proportions of American and British seamen which are contained in this aggregate of 85,799 men.

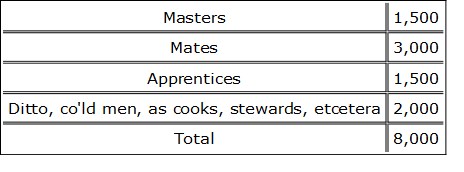

In the foreign trade we have to deduct the masters of the ships, the mates, and the boys who are apprenticed to learn their duty, and rise to mates and masters (not to serve before the mast). These I estimate at:—

which, deducted from 30,333, will leave 22,333 seamen in the foreign trade; who, with a slight intermixture of Swedes, Danes, and, more rarely, Americans, may be asserted to be all British seamen.

The next item is that of the men employed in the whale fishery; and, as near as I can ascertain the fact, the proportions are two-thirds Americans to one-third British. The total is 5,633; out of which 3,756 art Americans, and 1,877 British seamen.

The coasting trade employs 39,000 men; but only a small proportion of them can be considered as seamen, as it embraces all the internal river navigation.

The steam navigation employs 6,500 men, of whom of course not one in ten is a seaman.

The fisheries for cod and herring employ about 4,333 men; they are a mixture of Americans, Nova Scotians, and British, but the proportions cannot be ascertained; it is supposed that about one-half are British subjects, i.e. 2,166.

When, therefore, I estimate that the Americans employ at least thirty thousand of our seamen in their service, I do not think, as my subsequent remarks will prove, that I am at all overrating the case.

The questions which are now to be considered are, the nature of the various branches in which the seamen employed in the American marine are engaged, and how far they will be available to America in case of a war.

The coasting trade is chiefly composed of sloops, manned by two or three men and boys. The captain is invariably part, if not whole, owner of the vessel, and those employed are generally his sons, who work for their father, or some emigrant Irishmen, who, after a few months practice, are fully equal to this sort of fresh-water sailing. From the coasting trade, therefore, America would gain no assistance. Indeed, the majority of the coasting trade is so confined to the interior, that it would not receive much check from a war with a foreign country.

The coast fisheries might afford a few seamen, but very few; certainly not the number of men required to man her ships of war. As in the coasting trade, they are mostly owners or partners. In the whale fishery much the same system prevails; it is a common speculation; and the men embarking stipulate for such a proportion of the fish caught as their share of the profits. They are generally well to do, are connected together, and are the least likely of all men to volunteer on board of the American navy. They would speculate in privateers, if they did anything.

From steam navigation, of course, no seamen could be obtained.

Now, as all service is voluntary, it is evident that the only chance America has of manning her navy is from the thirty thousand British seamen in her employ, the other branches of navigation either not producing seamen, or those employed in them being too independent in situation to serve as foremast men. When I was at the different seaports, I made repeated inquiries as to the fact, if ever a lad was sent to sea as foremast-man, and I never could ascertain that it ever was the case. Those who are sent as apprentices, are learning their duty to receive the rating of mates, and ultimately fulfil the office of captains; and it may here be remarked, that many Americans, after serving as captains for a few years, return on shore and become opulent merchants; the knowledge which they have gained during their maritime career proving of the greatest advantage to them. There are a number of free black and coloured lads who are sent to sea, and who, eventually, serve as stewards and cooks; but it must be observed, that the masters and mates are not people who will enter before the mast and submit to the rigorous discipline of a government vessel, and the cooks and stewards are not seamen; so that the whale dependence of the American navy, in case of war, is upon the British seamen who are in her foreign trade and whale fisheries, and in her men-of-war in commission during the peace.

If America brings up none of her people to a seafaring life before the mast, now that her population is upwards of 13,000,000, still less likely was she to have done it when her population was less, and the openings to wealth by other channels were greater: from whence it may be fairly inferred, that, during our continued struggle with France, when America had the carrying trade in her hands, her vessels were chiefly manned by british seamen; and that when the war broke out between the two countries, the same British seamen who were in her employ manned her ships of war and privateers. It may be surmised that British seamen would refuse to be employed against their country. Some might; but there is no character so devoid of principle as the British sailor and soldier. In Dibdin’s songs, we certainly have another version, “True to his country and king,” etcetera, but I am afraid they do not deserve it: soldiers and sailors are mercenaries; they risk their lives for money; if is their trade to do so; and if they can get higher wages they never consider the justice of the cause, or whom they fight for. Now, America is a country peculiarly favourable for those who have little conscience or reflection; the same language is spoken there; the wages are much higher, spirits are much cheaper, and the fear of dejection or punishment is trifling: nay, there is none; for in five minutes a British seaman may be made a bona fide American citizen, and of course an American seaman. It is not surprising, therefore, that after sailing for years out of the American ports, in American vessels, the men, in case of war, should take the oath and serve. It is necessary for any one wanting to become an American citizen, that he should give notice of his intention; this notice gives him, as soon as he has signed his declaration, all the rights of an American citizen, excepting that of voting at elections, which requires a longer time, as specified in each state. The declaration is as follows:—

“That it is his bona fide intention to become a citizen of the United States, and to renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign power, potentate, state, or sovereignty whatever, and particularly to Victoria, the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to whom he is now a subject.” Having signed this document, and it being publicly registered, he becomes a citizen, and may be sworn to as such by any captain of merchant vessel or man-of-war, if it be required that he should do so.

During the last war with America, the Americans hit upon a very good plan as regarded the English seamen whom they had captured in our vessels. In the daytime the prison doors were shot and the prisoners were harshly treated; but at night, the doors were left open: the consequence was, that the prisoners whom they had taken added to their strength, for the men walked out, and entered on board their men-of-war and privateers.

This fact alone proves that I have not been too severe in my remarks upon the character of the English seamen; and since our seamen prove to be such “Dugald Dalgettys,” it is to be hoped that, should we be so unfortunate as again to come in collision with America, the same plan may be adopted in this country.

Now, from the above remarks, three points are clearly deducible:—

1. That America always has obtained, and for a long period to come will obtain, her seamen altogether from Great Britain.

2. That those seamen can be naturalised immediately, and become American seamen by law.

3. That, under present circumstances, England is under the necessity of raising seamen, not only for her own navy, but also for the Americans; and that, in proportion as the commerce and shipping of America shall increase, so will the demand upon us become more onerous; and that should we fail in producing the number of seamen necessary for both services, the Americans will always be full manned, whilst any defalcation must fall upon ourselves.

And it may be added that, in all cases, the Americans have the choice and refusal of our men; and, therefore, they have invariably all the prime and best seamen which we have raised.

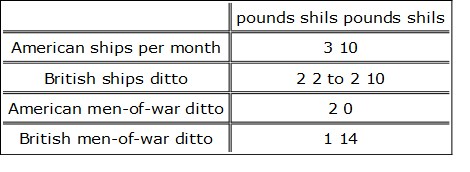

The cause of this is as simple as it is notorious; it is the difference between the wages paid in the navies and merchant vessels of the two nations:

It will be observed, that in the American men-of-war the able-seaman’s pay is only 2 pounds; the consequence is that they remain for months in port without being able to obtain men.

But we must now pass by this cause, and look to the origin of it; or, in other words, how is it that the Americans are able to give such high wages to our seamen as to secure the choice of any number of our best men for their service; and how is it that they can compete with, and even under-bid, our merchant vessels in freight, at the same time that they sail at a greater expense?

This has arisen partly from circumstances, partly from a series of mismanagement on our part, and partly from the fear of impressment. But it is principally to be ascribed to the former peculiarly unscientific mode of calculating the tonnage of our vessels; the error of which system induced the merchants to build their ships so as to evade the heavy channel and river duties; disregarding all the first principles of naval architecture, and considering the sailing properties of vessels as of no consequence.

The fact is, that we over-taxed our shipping.

In order to carry as much freight as possible, and, at the same time, to pay as few of the onerous duties, our mercantile shipping generally assumed more the form of floating bores of merchandise than sailing vessels; and by the false method of measuring the tonnage, they were enabled to carry 600 tons, when, by measurement, they were only taxed as being of the burden of 400 tons: but every increase of tonnage thus surreptitiously obtained, was accompanied with a decrease in the sailing properties of the vessels. Circumstances, however, rendered this of less importance during the war, as few vessels ran without the protection of a convoy; and it must be also observed, that vessels being employed in one trade only, such as the West India, Canada, Mediterranean, etcetera, their voyages during the year were limited, and they were for a certain portion of the year unemployed.

During the war the fear of impressment was certainly a strong inducement to our seamen to enter into the American vessels, and naturalise themselves as American subjects; but they were also stimulated even at that period, by the higher wages, as they still are now that the dread of impressment no longer operates upon them.

It appears, then, that from various causes, our merchant vessels have lost their sailing properties, whilst the Americans are the fastest sailers in the world; and it is for that reason, and no other, that, although sailing at a much greater expense, the Americans can afford to outbid us, and take all our best seamen.

An American vessel is in no particular trade, but ready and willing to take freight anywhere when offered. She sails so fast that she can make three voyages whilst one of our vessels can make but two: consequently she has the preference, as being the better manned, and giving the quickest return to the merchant; and as she receives three freights whilst the English vessel receives only two, it is clear that the extra freight wilt more than compensate for the extra expense the vessel sails at in consequence of paying extra wages to the seamen. Add to this, that the captains, generally speaking, being better paid, are better informed, and more active men; that, from having all the picked seamen, they get through their work with fewer hands; that the activity on board is followed up and supported by an equal activity on the part of the agents and factors on shore—and you have the true cause why America can afford to pay and secure for herself all our best seamen.

One thing is evident, that it is a mere question of pounds, shillings, and pence, between us and America, and that the same men who are now in the American service would, if our wages were higher than those offered by America, immediately return to us and leave her destitute.

That it would be worth the while of this country, in case of a war with the United States, to offer 4 pounds a-head to able seamen, is most certain. It would swell the naval estimates, but it would shorten the duration of the war, and in the end would probably be the saving of many millions. But the question is, cannot and ought not something to be done, now in time of peace, to relieve our mercantile shipping interest, and hold out a bounty for a return to those true principles of naval architecture, the deviation from which has proved to be attended with such serious consequences.

Fast-sailing vessels will always be able to pay higher wages than others, as what they lose in increase of daily expense, they will gain by the short time in which the voyage is accomplished; but it is by encouragement alone that we can expect that the change will take place. Surely some of the onerous duties imposed by the Trinity House might be removed, not from the present class of vessels, but from those built hereafter with first-rate sailing properties. These, however, are points which call for a much fuller investigation than I can here afford them; but they are of vital importance to our maritime superiority, and as such should be immediately considered by the government of Great Britain.

Volume Three—Chapter Six

Remarks—SlaveryIt had always appeared to me as singular that the Americans, at the time of their Declaration of Independence, took no measures for the gradual, if not immediate, extinction of slavery; that at the very time they were offering up thanks for having successfully struggled for their own emancipation from what they considered foreign bondage, their gratitude for their liberation did not induce them to break the chains of those whom they themselves held in captivity. It is useless for them to exclaim, as they now do, that it was England who left them slavery as a curse and reproach us as having originally introduced the system among them. Admitting, as is the fact, that slavery did commence when the colonies were subject to the mother country admitting that the petitions for its discontinuance were disregarded, still there was nothing to prevent immediate manumission at the time of the acknowledgement of their independence by Great Britain. They had then everything to recommence they had to select a new form of government, and to decide upon new laws; they pronounced, in their declaration, that “all men were equal;” and yet, in the face of this declaration, and their solemn invocation to the Deity, the negroes, in their fetters, pleaded to them in vain.

I had always thought that this sad omission, which has left such an anomaly in the Declaration of Independence as to have made it the taunt and reproach of the Americans by the whole civilised world, did really arise from forgetfulness; that, as is but too often the case, when we are ourselves made happy, the Americans in their joy at their own deliverance from the foreign yoke, and the repossessing themselves of their own rights, had been too much engrossed to occupy themselves with the undeniable claims of others. But I was mistaken; such was not the case, as I shall presently show.

In the course of one of my sojourns in Philadelphia, Mr Vaughan, of the Athenium of that city, stated to me that he had found the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, in the hand-writing of Mr Jefferson, and that it was curious to remark the alterations which had been made previous to the adoption of the manifesto which was afterwards promulgated. It was to Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin, that was entrusted the primary drawing up of this important document, which was then submitted to others, and ultimately to the Convention, for approval and it appears that the question of slavery had not been overlooked when the document was first framed, as the following clause, inserted in the original draft by Mr Jefferson, (but expunged when it was laid before the Convention,) will sufficiently prove. After enumerating the grounds upon which they threw off their allegiance to the king of England, the Declaration continued in Jefferson’s nervous style:

“He (the king) has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty, in the person of a distant people who never offended him; captivating and carrying them into slavery, in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain, determined to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold; he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce; and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished dye, he is now exciting these very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.”

Such was the paragraph which had been inserted by Jefferson, in the virulence of his democracy, and his desire to hold up to detestation the king of Great Britain. Such was at that time, unfortunately, the truth; and had the paragraph remained, and at the same time emancipation been given to the slaves, it would have been a lasting stigma upon George the Third. But the paragraph was expunged; and why I because they could not hold up to public indignation the sovereign whom they had abjured, without reminding the world that slavery still existed in a community which had declared that “all men were equal;” and that if, in a monarch, they had stigmatised it as “violating the most sacred rights of life and liberty,” and “waging cruel war against human nature,” they could not have afterward been so barefaced and unblushing as to continue a system which was at variance with every principle which they professed.

Note. Miss Martineau, in her admiration of democracy, says, that, in the formation of the government, “The rule by which they worked was no less than the golden one, which seems to have been, by some unlucky chance, omitted in the Bibles of other statesmen, ‘Do unto others as ye would that they should do unto you’” I am afraid the American Bible, by some unlucky chance, has also omitted that precept.