полная версия

полная версияDiary in America, Series One

No. 8—was at large. He had been appointed apothecary to the prison; of course he was not strictly confined, and was in a comfortable room. He was a shrewd man, and evidently well educated; he had been reduced to beggary by his excesses, and being too proud to work, he had not been too proud to commit forgery. I had a long conversation with him, and he made some sensible remarks upon the treatment of prisoners, and the importance of delegating the charge of prisoners to competent persons. His remarks also upon American juries were very severe, and, as I subsequently ascertained, but too true.

No. 9—a young woman about nineteen, confined for larceny; in other respects a good character. She was very quiet and subdued, and said that she infinitely preferred the solitude of the penitentiary to the company with which she must have associated had she been confined in a common gaol. She did not appear at all anxious for the expiration of her term. Her cell was very neat, and ornamented with her own hands in a variety of ways. I observed that she had a lock of hair on her forehead which, from the care taken of it, appeared to be a favourite, and, as I left the cell, I said—“You appear to have taken great pains with that lock of hair, considering that you have no one to look at you?”—“Yes, sir,” replied she; “and if you think that vanity will desert a woman, even in the solitude of a penitentiary, you are mistaken.”

When I visited this girl a second time, her term was nearly expired; she told me that she had not the least wish to leave her cell, and that, if they confined her for two years more, she was content to stay. “I am quite peaceful and happy here,” she said, and I believe she really spoke the truth.

No. 10—a free mulatto girl, about eighteen years of age, one of the most forbidding of her race, and with a physiognomy perfectly brutal; but she evidently had no mean opinion of her own charms: her woolly hair was twisted into at least fifty short plaits, and she grinned from ear to ear as she advanced to meet me. “Pray, may I inquire what you are imprisoned for?” said I.—“Why, sir,” replied she, smirking, smiling, and coquetting, as she tossed her head right and left,—“If you please, sir, I was put in here for poisoning a whole family.” She really appeared to think that she had done a very praiseworthy act. I inquired of her if she was aware of the heinousness of her offence. “Yes, she knew it was wrong, but if her mistress beat her again as she had done, she thought she would do it again. She had been in prison three years, and had four more to remain.” I asked her if the fear of punishment—if another incarceration for seven years would not prevent her from committing such a crime a second time. “She didn’t know; she didn’t like being shut up—found it very tedious, but still she thought—was not quite sure—but she thought that, if ill-treated, she should certainly do it again.”

I paid a second visit to this amiable young lady, and asked her what her opinion was then.—“Why, she had been thinking, but had not exactly made up her mind—but she still thought—indeed, she was convinced—that she should do it again.”

I entered many other cells, and had conversations with the prisoners but I did not elicit from them any thing worth narrating. There is, however, a great deal to be gained from the conversation which I have recorded. It must be remembered, that observations made by one prisoner, which struck me as important, if not made by others, were put as questions by me; and I found that the opinions of the most intelligent, although differently expressed, led to the same result—that the present system of the Philadelphia penitentiary was the best that had been invented. As the schoolmaster said, if it did no good, it could do no harm. There is one decided advantage in this system, which is, that they all learn a trade, if they had not one before; and, when they leave the prison, have the means of obtaining an honest livelihood, if they wish so to do themselves, and are permitted so to do by others. Here is the stumbling-block which neutralises almost all the good effects which might be produced by the penitentiary system. The severity and harshness of the world; the unchristianlike feeling pervading society, which denies to the penitent what individually they will have to plead for themselves at the great tribunal, and which will not permit that punishment, awarded and suffered, can expiate the crime; on this point, there is no hope of a better feeling being engendered. Mankind have been, and will be, the same; and it is only to be hoped that we may receive more mercy in the next world than we are inclined to extend toward our fellow-creatures in this.

As I have before observed, I care little for the observations or assertions of directors or of officers entrusted with the charge of the penitentiaries and houses of correction; they are unintentionally biased, and things that appear to them to be mere trifles are very often extreme hardships to the prisoners. It is not only what the body suffers, but what the mind suffers, which must be considered; and it is from the want of this consideration that arise most of the defects in those establishments, not only in America, but everywhere else.

During my residence in the United States, a little work made its appearance, which I immediately procured; it was the production of an American, a scholar, once in the best society, but who, by intemperance, had forfeited his claim to it. He wrote the very best satirical poem I ever read by an American, full of force, and remarkable for energetic versification; but intemperance, the prevalent vice of America, had induced him to beggary and wretchedness, he was (by his own request I understand) shut up in the house of correction at South Boston, that he might, if possible, be reclaimed from intemperance; and, on his leaving it, he published a small work, called “The Rat-Trap, or Cogitations of a Convict in the House of Correction.” This work bears the mark of a reflective, although buoyant mind; and as he speaks in the highest terms of Mr Robbins, the master, and bestows praise generally when deserved, his remarks, although occasionally jocose, are well worthy of attention and I shall, therefore, introduce a few of them to the reader.

His introduction commences thus:—

“I take it for granted that one of every two individuals in this most moral community in the world has been, will be, or deserves or fears to be, in the house of correction. Give every man his deserts, and who shall escape whipping? This book must, therefore, be interesting, and will have a good circulation—not, perhaps, in this state alone. The state spends its money for the above institution, and, therefore, has a right to know what it is; a knowledge which can never be obtained from the reports of the authorities, the cursory observations of visitors, or the statements of ignorant and exasperated convicts.

“‘What thief e’er felt the halter draw,With good opinion of the law.’“It has been my aim to furnish such knowledge, and it cannot be denied that I have had the best opportunities to obtain it.”

To show the prevalence of intemperance in this country among the better classes, read the following:—

“On entering the wool-shop, a man nodded to me, whom I immediately recognised as a lawyer of no mean talent, who had, at no very distant period, been an ornament of society, and a man well esteemed for many excellent qualities, all of which are now forgotten, while his only fault, intemperance, remains engraven on steel. This was not his first term, or his second, or his third. At this time of writing he is discharged, a sober man, anxious for employment, which he cannot get. His having been in the house of correction shuts every door against him, and he must have more than ordinary firmness if he does not relapse again. From my inmost soul I pity him. Another aged man I recognised as a doctor of medicine: his grey hairs would have been venerable in any other place.”

The labour in this house of correction which he describes is chiefly confined to wool-picking, stone-cutting, and blacksmiths’ work. The fare he states to be plentiful, but not of the very best quality. Speaking of ill-treatment, he says:—

“The convicts all have the privilege of complaint against officers; but while I was there no one used it but myself. I believe they dared not. The officer would probably deny or gloss over the cause of complaint, and his word would be believed rather than that of the convict; and his power of retaliation is so tremendous, that few would care to brave it. The chance is ten to one that a complaint to the directors would be falsified and proved fruitless; and the visit of the governor, council, and magistrates, for the purpose of inquiry, is mere matter of form. When they asked me if I had reason to complain of my treatment, I answered in the negative, because I really had none; but had they asked me if there was any defect in the institution, I would have pointed out a good many.”

The monotony of their existence is well described:—

“Few incidents chequered the monotony of our existence. ‘Who has got a piece of steel in his eye?’—‘Who has gone to the hospital?’—‘How many came to-day in the carry-all?’ were almost the only questions we could ask. A man falling from the new prison, and breaking his bones in a fashion not to be approved, was a conversational godsend. One day the retiring tide left a small box on the sands at the bottom of the house of correction wharf, which was picked up by a convict, and found to contain the bequest of some woman who had ‘loved not wisely, but too well,’ namely, a pair of new-born infants. In my mind, their fate was happy. If they never knew woman’s tenderness, neither did they ever know woman’s falsehood. There is less pleasure than pain in this bad world, and the earlier we take leave of it the better.”

He complains of due regard not being paid to the cleanliness of the prisoners:—

“A great defect in the police of the house was the want of baths. We were shaved, or rather scraped, but once a week. Washing one’s face and hands in ice-cold water of a winter morning, is little better than no ablution at all. The harbour water is interdicted, lest the convicts should swim away, and in the stone-shop there are no conveniences for bathing whatever: they would cost something! In the wool-shop, forty men have one tubful of warm water once a-week. When I say that shirts are worn a week in summer, and (as well as drawers) two or three weeks in winter, it will at once be conceded that some farther provision for personal cleanliness is imperatively demanded. I hope neither this nor any other remark I may think fit to make will be taken as emanating from a fault-finding spirit, since, while I pronounce upon the disease, I suggest the remedy.”

Speaking of his companions, he says:—

“I had expected to find myself linked with a band of most outrageous ruffians, but such did not prove to be the case. Few of them were decidedly of a vicious temperament. The great fault with them seemed to be a want of moral knowledge and principle. Were I to commit a theft I should think myself unworthy to live an instant; but some of them spoke of the felonies for which they were adjudged to suffer with as much nonchalance as if they were the every-day business of life, without scruple and without shame. Few of them denied the justice of their sentences; and if they expressed any regret, it was not that they had sinned, but that they had been detected. The duration of the sentence, the time or money lost, the physical suffering, was what filled their estimate of their condition. Many had groans and oaths for a lost dinner, a night in the cells, or a tough piece of work, but none had a tear for the branding infamy of their conviction. Yet some, even of the most hardened, faltered, and spoke with quivering lip and glistening eye, when they thought of their parents, wives, and children. The flinty Horeb of their souls sometimes yielded gushing streams to the force of that appeal. But there were very few who felt any shame on their own account. Their apathy on the point of honour was amazing. A young man, not twenty-five years old, in particular, made his felonies his glory, and boasted that he had been a tenant of half the prisons in the United States. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for stealing a great number of pieces of broadcloth, which he unblushingly told me he had lodged in the hands of a receiver of stolen goods, and expected to receive the value at the expiration of his sentence. He relied on the proverbial ‘honour among thieves.’ That fellow ought to be kept in safe custody the remainder of his natural life.”

Certainly those remarks do not argue much for the reformation of the culprit.

By his account, a parsimony in every point appears to be the great desideratum aimed at. Speaking of the chaplain to the institution, he says:—

“Small blame to him; I honour and respect the man, though I laugh at the preacher. And I say, that seven hundred and thirty sermons per annum, for three hundred dollars and a weekly dinner, are quite pork enough for a shilling. No man goeth a warfare on his own charges, and the labourer is worthy of his hire. I do not see how he can justify such wear and tear of his pulmonary leather, for so small a sum, to his conscience. What is a sixpenny razor or a nine-shilling sermon? Neither can be expected to cut—not but his sermons would be very good for the use of glorified saints—but, alas! there are none such in the House of Correction. What is the inspiration of a penny-a-liner? I will suppose that one of the hearers is a sailor, who would relish and appreciate a sausage or a lobscouse. Mr – sets blanc mange before him.—Messrs of the city government give your chaplain two thousand dollars a-year, so that he may reside in the house of correction, without leaving his family to starvation; let him visit each individual, learn his circumstances and character, and sympathise with him in all his sorrows, and, my word for it, Mr – will have the love and confidence of all. He will be an instrument of great good by his counsel and exhortations. But as for his public preaching, this truly good, pious, and learned man might as well sing psalms to a mad horse. Fishes will not throng to St. Anthony, or swine listen to the exorcism of an apostle, in these godless days. If you think he will be overpaid for his services, you may braze the duty of a schoolmaster, who is very much needed, to that of a ghostly adviser.

“Mr – never fails to pray strenuously that the master and officers may be supported and sustained, which has given rise to the following tin-pot epigram:—

“Support the master and the overseers,O Lord! so runs our chaplain’s weekly ditty;Unreasonable prayers God never hears,He knows that they’re supported by the city.”He complains bitterly of the convicts not being permitted the use of any books but the Bible and temperance Almanac. It is rather strange, but he says that he supposes that a full half of the inmates of the house of correction can neither read nor write.

“Is it pleasant to look back on follies, vices, crimes; presently on blasted hopes, iron bars, and unrequited labour; and forward upon misery, starvation, and a world’s scorn? In some degree the malice of this regulation, which ought only to be inscribed on the statute-book of hell, is impotent. The small glimpse of earth, sea, and sky a convict can command, a spider crawling upon the wall, the very corners of his cell, will serve, by a strong effort, for occupation for his thoughts. Read the following tea-pot-graven monologue, written by some mentally-suffering convict, and reflect upon it:—

“Stone walls and iron bars my frame confine,But the full liberty of thought is mine,Sad privilege! the mental glance to castO’er crimes, o’er follies, and misconduct past.Oh wretched tenant of a guarded cell,Thy very freedom makes thy mind a hell.Come, blessed death; thy grinded dart to me,Shall the bless’d signal of deliverance be;With thy worst agonies were cheaply bought,A last release, a final rest from thought.”“If the pains of a prison be not enough for you, I will teach you a lesson in the art of torture which I learned from our chaplain, or one of his substitutes.—‘Make your cells round and smooth; let there be no prominent point for the eye to rest upon, so that it must necessarily turn inward, and I will warrant that you will soon have the pleasure of seeing your victim frantic.’ Look well to the temperance trash you physic us with, and you will find, in the Almanac for 1837, a serious attempt to make Napoleon Bonaparte out a drunkard, and to prove that a rum-bottle lost him the battle of Waterloo. The author must himself have been drunk when he wrote it. Are you not ashamed to set such pitiful cant, I will not say such wilful falsehood and slander, before any rational creature? Did you not know that an overcharged gun would knock the musketeer over by its recoil? I do not tell you to give the convicts all and any books they may desire; but pray what harm would an arithmetic do, unless it taught them to refute the statistics of your lying almanac, which gravely advises farmers to feed their hogs with apples, to prevent folks from getting drunk on cider? Why not tell them to feed their cattle with barley and wheat for the same reason? What mind was ever corrupted by Murray’s Grammar, or Washington Irving’s Columbus? When was ever falsehood the successful pioneer of truth!”

His remarks upon visitors being permitted to see the convicts are good.

“Among the annoyances, which others as well as myself felt most galling, was the frequent intrusion of visitors, who had no object but the gratification of a morbid curiosity. Know all persons, that the most debased convict has human feelings, and does not like to be seen in a parti-coloured jacket. If you want to see any convict for any good reason, ask the master to let you meet him in his office; and even there, you may rely upon it, your visit will be painful enough; to be stared at by the ignorant and the mean with feelings of pity, as if one were some monster of Ind, was intolerable. I hope a certain connexion of mine, who came to see me unasked and unwelcome, and brought a stranger with him to witness my disgrace, may never feel the pain he inflicted on me. To a kind-hearted ‘Mac,’ who came in a proper and delicate way to comfort when I thought all the world had forsaken me, I tender my most grateful thanks. His kindness shall be remembered by me while memory holds her seat. Let the throng of uninvited fools who swarmed about us, accept the following sally of the house of correction muse, from the pen, or rather the fork, of a fellow convict. It may operate to edification.

“To Our Visitors.“By gazing at us, sirs, pray what do you mean?Are we the first rascals that ever were seen?Look into your mirrors—perhaps you may findAll villains are not in South Boston confined.“I’m not a wild beast, to be seen for a penny;But a man, as well made and as proper as any;And what we most differ in is, well I wot,That I have my merits, and you have them not.“I own I’m a drunkard, but much I inclineTo think that your elbow crooks as often as mine;Ay, breathe in my face, sir, as much as you will—One blast of your breath is as good as a gill.“How kind was our country to find us a homeWhere duns cannot plague us, or enemies come!And you from the cup of her kindness may drainA drop so sufficing, you’ll not drink again.“And now that by staring with mouth and eyes open,We have bruised the reeds that already were broken;Go home and, by dint of strict mental inspection,Let each make his own house a house of correction.“This morceau was signed ‘Indignans.’”

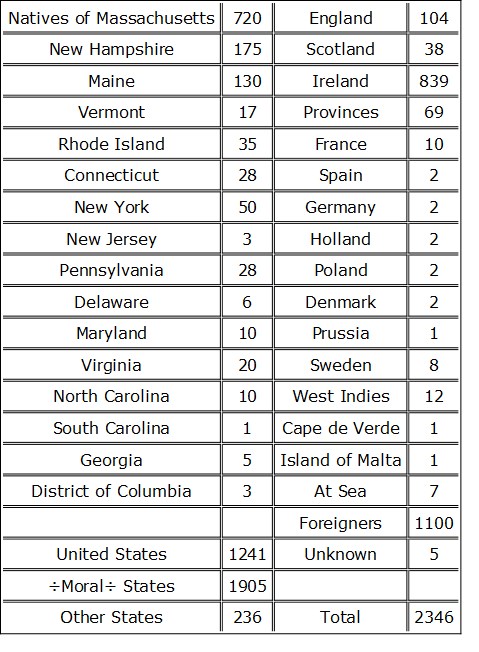

The following muster-roll of crime, as he terms it, which he obtained from the master of the prison, is curious, as it exemplifies the excess of intemperance in the United States—bearing in mind that this is the moral state of Massachusetts.

“The whole number of males committed to the house of correction from the time it was opened—July 1st, 1833, to September 1st, 1837,—was 1477. Of this number there were common drunkards 783, or more than one-half.

“The whole amount of females committed to this institution from the time it was opened to Sept 1837, was 869. Of this number there were common drunkards 430, very nearly one-half.

“And of the whole number committed there were—”

He sums up as follows:—

“I have nearly finished, but I should not do justice to my subject did I omit to advert to the beggarly catch-penny system on which the whole concern is conducted. The convicts raise pork and vegetables in plenty, but they must not eat thereof; these things must be sent to market to balance the debit side of the prison ledger. The prisoners must catch cold and suffer in the hospital, and the wool and stone shops, because it would cost something to erect comfortable buildings. They must not learn to read and write, lest a cent’s worth of their precious time should be lost to the city. They may die and go to hell, and be damned, for a resident physician and chaplain are expensive articles. They may be dirty; baths would cost money, and so would books. I believe the very Bibles and almanacks are the donation of the Bible and Temperance societies. Every thing is managed with an eye to money-making—the comfort or reformation, or salvation, of the prisoners are minor considerations. Whose fault is this?

“The fault, most frugal public, is your own. You like justice, but you do not like to pay for it. You like to see a clean, orderly, well conducted prison, and, as far as your parsimony will permit, such is the house of correction. With all its faults, it is still a valuable institution. It holds all, it harms few, and reforms some. It looks well, for the most has been made of matters. If you would have it perfect you must untie your purse-strings, and you will lose nothing by it in the end.”

Volume Three—Chapter Four

Remarks—ArmyIsolated as the officers are from the world, (for these forts are far removed from towns or cities,) they contrived to form a society within themselves, having most of them recourse to matrimony, which always gives a man something to do, and acts as a fillip upon his faculties, which might stagnate from such quiet monotony. The society, therefore, at these outposts is small, but very pleasant. All the officers being now educated at West Point, they are mostly very intelligent and well informed, and soldiers’ wives are always agreeable women all over the world. The barracks turned out also a very fair show of children upon the green sward. The accommodations are, generally speaking, very good, and when supplies can be received, the living is equally so; when they cannot, it can’t be helped, and there is so much money saved. A suttler’s store is attached to each outpost, and the prices of the articles are regulated by a committee of officers, and a tax is also levied upon the suttler in proportion to the number of men in the garrison, the proceeds of which are appropriated to the education of the children of the soldiers and the provision of a library and news-room. If the government were to permit officers to remain at any one station for a certain period, much more would be done; but the government is continually shifting them from post to post, and no one will take the trouble to sow when he has no chance of reaping the harvest. Indeed, many of the officers complained that they hardly had time to furnish their apartments in one fort when they were ordered off to another—not only a great inconvenience to them, but a great expense also.

The American army is not a favourite service, and this is not to be wondered at. It is ill-treated in every way; the people have a great dislike to them, which is natural enough in a Democracy; but what is worse, to curry favour with the people, the government very often do not support the officers in the execution of their duty. Their furloughs are very limited, and they have their choice of the outposts, where they live out of the world, or the Florida war, when they go out of it. But the greatest injustice is, that they have no half-pay: if not wishing to be employed they must resign their commissions and live as they can. In this point there is a great partiality shown to the navy, who have such excellent half-pay, although to prevent remarks at such glaring injustice to the other service, another term is given to the naval half-pay, and the naval officers are supposed to be always on service.