полная версия

полная версияDiary in America, Series One

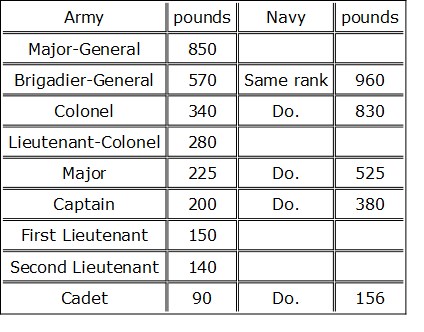

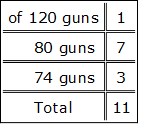

The officers of the army are paid a certain sum, and allowed a certain number of rations per month; for instance, a major-general has two hundred dollars per month, and fifteen rations: According to the estimated value of the rations, as given to me by one of the officers, the annual pay of the different grades will be, in our money, nearly as follows:—

Army.

The cavalry officers have a slight increase of pay.

The privates of the American regular army are not the most creditable soldiers in the world; they are chiefly composed of Irish emigrants, Germans, and deserters from the English regiments in Canada. Americans are very rare; only those who can find nothing else to do, and have to choose between enlistment and starvation, will enter into the American army. They do not, however, enlist for longer than three years. There is not much discipline, and occasionally a great deal of insolence, as might be expected from such a collection. Corporal punishment has been abolished in the American army except for desertion; and if ever there was a proof of the necessity of punishment to enforce discipline, it is the many substitutes in lieu of it, to which the officers are compelled to resort—all of them more severe than flogging. The most common is that of loading a man with thirty-six pounds of shot in his knapsack, and making him walk three hours out of four, day and night without intermission, with this weight on his shoulders, for six days and six nights; that is, he is compelled to walk three hours with the weight, and then is suffered to sit down one. Towards the close this punishment becomes very severe; the feet of the men are so sore and swelled, that they cannot move for some days afterwards. I inquired what would be the consequence if a man were to throw down his knapsack and refuse to walk. The commanding-officer of one of the forts replied, that he would be hung up by the thumbs till he fainted—a variety of piquetting. Surely these punishments savour quite as much of severity, and are quite as degrading as flogging.

The pay of an American private is good—fourteen dollars a month, out of which his rations and regimentals take eight dollars, leaving him six dollars a month for pleasure. Deserters are punished by being made to drag a heavy ball and chain after them, which is never removed day or night. If discharged, they are flogged, their heads shaved, and they are drummed out at the point of the bayonet.

From the conversations I have had with many deserters from our army, who were residing in the United States or were in the American service, I am convinced that it would be a very well-judged measure to offer a free pardon to all those who would return to Canada and re-enter the English service. I think that a good effective regiment would soon be collected, and one that you might trust on the frontiers without any fear of their deserting again; and it would have another good effect, that is, that their statements would prevent the desertion of others.

America, and its supposed freedom, is, to the British soldiers, an Utopia in every sense of the word. They revel in the idea; they seek it and it is not to be found. The greatest desertion from the English regiments is among the musicians composing the bands. There are so many theatres in America, and so few musicians, except coloured people, that instrumental performers of all kinds are in great demand. People are sent over to Canada, and the other British provinces to persuade these poor fellows to desert, promising them very large salaries, and pointing out to them the difference between being a gentleman in America and a slave in the English service. The temptation is too strong; they desert; and when they strive, they soon learn the value of the promises made to them, and find how cruelly they have been deceived.

The Florida war has been a source of dreadful vexation and expense to the United States, having already cost them between 20,000,000 and 30,000,000 of dollars, without any apparent prospect of its coming to a satisfactory conclusion. The American government has also very much injured its character, by the treachery and disregard of honour shown by it to the Indians, who have been, most of them, captured under a flag of truce. I have heard so much indignation expressed by the Americans themselves at this conduct that I shall not comment farther upon it. It is the Federal government, and not the officers employed, who must bear the onus. But this war has been mortifying, and even dangerous to the Americans in another point. It has now lasted three years and more. General after general has been superseded, because they have not been able to bring it to a conclusion; and the Indians have proved, to themselves and to the Americans, that they can defy them when they once get them among the swamps and morasses. There has not been one hundred Indians killed, although many of them have been treacherously kidnapped, by a violation of honour; and it is supposed that the United States have already lost one thousand men, if not more, in this protracted conflict.

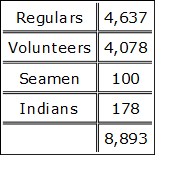

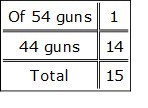

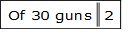

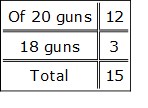

The aggregate force under General Jessup, in Florida, in November, 1837, was stated to be as follows:—

It is supposed that the number of Indians remaining in Florida do not amount, men, women, and children, to more than 1,500 and General Jessup has declared to the government that the war is impracticable.

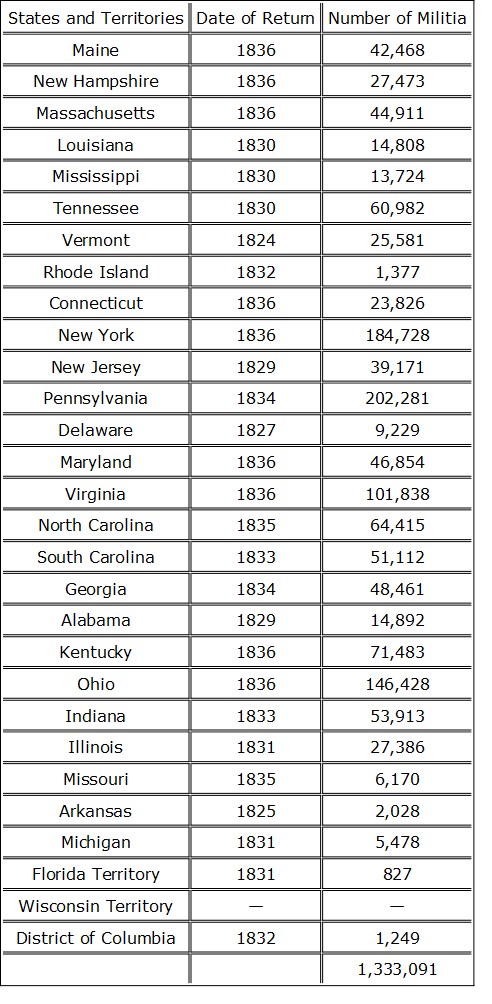

Militia.—The return of the militia of the United States, for the year 1837, is as follows:—

The number of Militia in the several states and territories, according to the statement of George Bomford, Colonel of Ordnance, dated 20th November, 1837.

This is an enormous force, but at the commencement of a war not a very effective one. In fact, there is no country in the world so defenceless as the United States, but, once roused up, no country more formidable if any (attempt) is made to invade its territories. At the outbreak of a war, the states have almost everything to provide; and although the Americans are well adapted as materials for soldiers, still they have to be levied and disciplined. At the commencement of hostilities, it is not improbable that a well-organised force of 30,000 men might walk through the whole of the Union, from Maine to Georgia; but it is almost certain that not one man would ever get back again, as by that time the people would have been roused and excited, armed and sufficiently disciplined; and their numbers, independent of their bravery, would overwhelm three or four times the number I have mentioned.

Another point must not pass unnoticed, which is, that in America, the major part of which is still an uncleared country, the system of warfare naturally partakes much of the Indian practices of surprise and ambuscade; and the invaders will always have to labour under the great disadvantage of the Americans having that perfect knowledge of the country which the former have not.

Most of the defeats of the British troops have been occasioned by this advantage on the part of the Americans, added to the impracticability of the country rendering the superior discipline of the British of no avail. Indeed the great advantages of knowing the country were proved by the American attempts to invade Canada during the last war, and which ended in the capitulation of General Hull. In an uncleared country, even where large forces meet, each man, to a certain degree, acts independently, taking his position, perhaps, behind a tree (treeing it, as they term it in America), or any other defence which may offer. Now, it is evident that, skilled as all the Americans are in fire-arms, and generally using rifles, a disciplined English soldier, with his clumsy musket, fights at a disadvantage; and, therefore, with due submission to his Grace, the Duke of Wellington was very wrong when he stated, the other day in the House of Lords, that the militia of Canada should be disbanded, and their place supplied by regular troops from England. The militia of Upper Canada are quite as good men as the Americans, and can meet them after their own fashion. A certain proportion of regulars are advantageous, as they are more steady, and in case of a check can be more depended upon; but it is not once in five times that they will, either in America or Canada, be able to bring their concentrated discipline into play. But if the Americans have not the discipline of our troops, their courage is undoubted, and even upon a clear plain the palm of victory will always be severely disputed. A Vermonter, surprised for a moment at finding himself in a charge of bayonets, with the English troops, eyed his opponents, and said, “Well I calculate my piece of iron is as good as yourn, anyhow,” and then rushed to the attack. People who “calculate” in that way are not to be trifled with, as the annals of history fully demonstrate.

A war between America and England is always to be deprecated. Notwithstanding that the countries are severed, still the Americans are our descendants; they speak the same language, and (although they do not readily admit it) still look up to us as their mother country. It is true that this feeling is fast wearing away, but still it is not yet effaced. It is true also that, in their ambition and their covetousness, they would destroy the mutual advantages derived by both countries from our commercial relations, that they might, by manufacturing as well as producing, secure the whole profits to themselves. But they are wrong; for great as America is becoming, the time is not yet arrived when she can compete with English capital, or work for herself without it. But there is another reason why a war between the two countries is so much to be deprecated, which is, that is must ever be a cruel and an irritating war. To attack the Americans by invasion will always be hazardous, and must ultimately prove disastrous. In what manner, then, is England to avenge any aggression that may be committed by the Americans? All she can do is to ravage, burn, and destroy; to carry the horrors of war along their whole extended line of coast, distressing the non-combatants, and wreaking vengeance upon the defenceless.

Dreadful to contemplate as this is, and, even more dreadful the system of stimulating the Indian tribes to join us, adding scalping, and the murdering of women and children, to other horrors, still it is the only method to which England could resort, and, indeed, a method to which she would be warranted to resort, in her own behoof. Moreover, in case of a future war, England must not allow it to be of such short duration as was the last; the Americans must be made to feel it, by its being protracted until their commerce is totally annihilated, and their expenses are increased in proportion with the decrease of their means.

Let it not be supposed that England would harass the coasts of America, or raise the Indian tribes against her, from any feeling of malevolence, or any pleasure in the sufferings which must ensue. It would be from the knowledge of the fact that money is the sinews of war; and consequently that, by obliging the Americans to call out so large a force as she must do to defend her coast and to repel the Indians, she would be put to such an enormous expense, as would be severely felt throughout the Union, and soon incline all parties to a cessation of hostilities. It is to touch their pockets that this plan must and will be resorted to; and a war carried on upon that plan alone, would prove a salutary lesson to a young and too ambitious a people. Let the Americans recollect the madness of joy with which the hats and caps were thrown up in the air at New York, when, even after so short a war with England, they heard that the treaty of peace had been concluded; and that too at a time when England was so occupied in a contest, it may be said, with the whole world, that she could hardly divert a portion of her strength to act against America: then let them reflect how sanguinary, how injurious, a protracted war with England would be, when she could direct her whole force against them. It is, however, useless to ask a people to reflect who are governed and ruled by the portion who will not reflect. The forbearance must be on our part; and, for the sake of humanity, it is to be hoped that we shall be magnanimous enough to forbear, for so long as may be consistent with the maintenance of our national honour.

Volume Three—Chapter Five

Remarks—American MarineIt may be inferred that I naturally directed my attention to everything connected with the American marine, and circumstances eventually induced me to search much more minutely into particulars than at first I had intended to do.

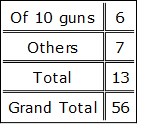

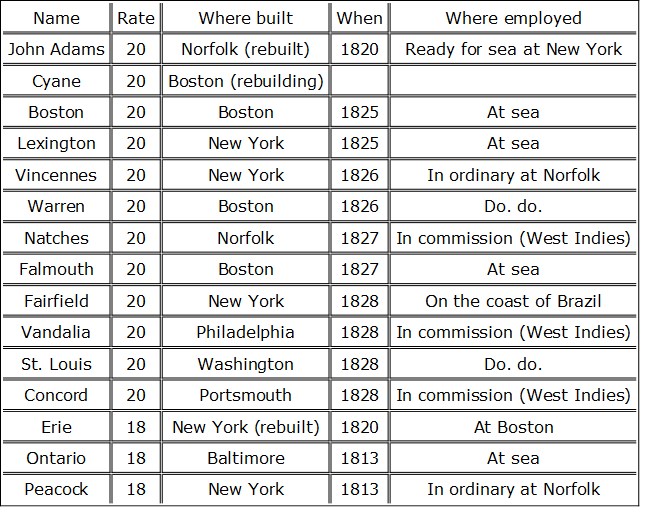

The present force of the American navy is rated as follows:—

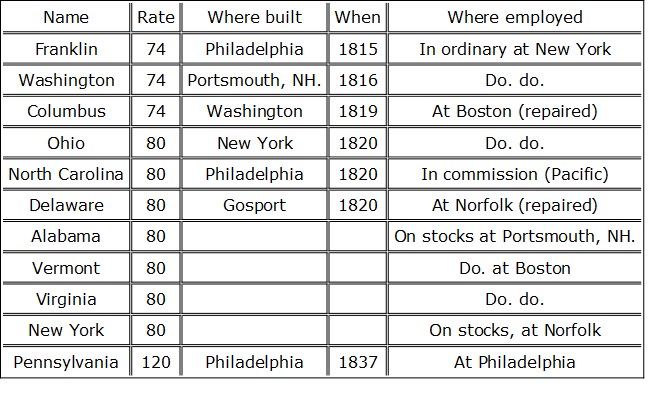

Ships of the Line

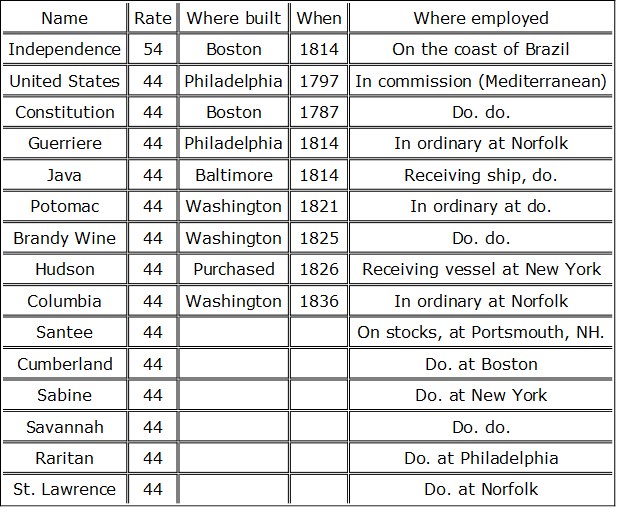

Frigates, 1st Class.

Frigates, 2nd Class

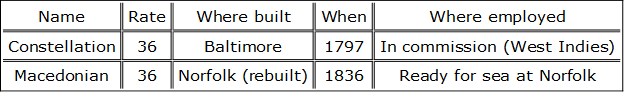

Sloops

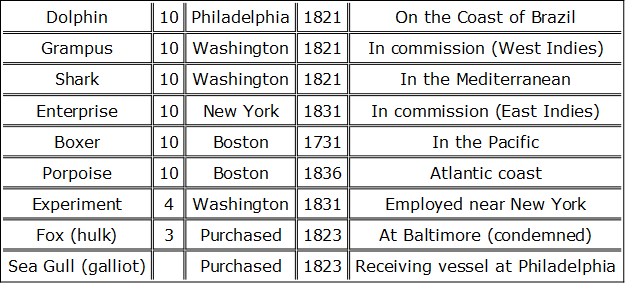

Schooners

Vessels of War of the United States Navy, September 1837.

Ships of the Line

Frigates, 1st Class

Frigates, 2nd Class

Sloops of War

Schooners

Exploring Vessels

The ratings of these vessels will, however, very much mislead people as to the real strength of the armament. The 74’s and 80’s are in weight of broadside equal to most three-decked ships; the first-class frigates are double-banked of the scantling, and carrying the complement of men of our 74’s. The sloops are equally powerful in proportion to their ratings, most of them carrying long guns. Although flush vessels, they are little inferior to a 36-gun frigate in scantling, and are much too powerful far any that we have in our service, under the same denomination of rating. All the line-of-battle ships are named after the several states, the frigates after the principal rivers, and the sloops of war after the towns, or cities, and the names are decided by lot.

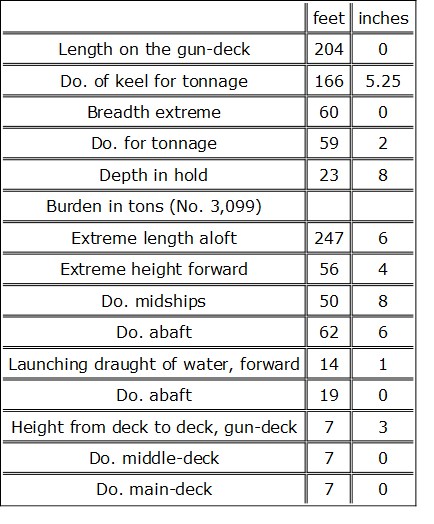

It is impossible not to be struck with the beautiful architecture in most of these vessels. The Pennsylvania, rated 120 guns, on four decks, carrying 140, is not by any means so perfect as some of the line-of-battle ships.

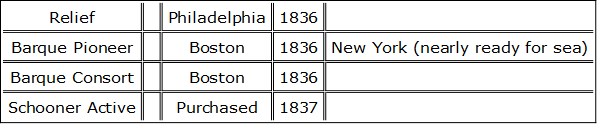

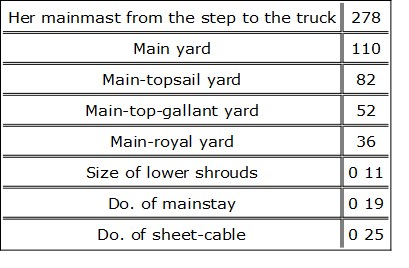

Note. The following are the dimensions given me of the ship of the line Pennsylvania:—

Burthen 3366 tons, and has ports for 140 guns, all long thirty-two pounders, throwing 2240 pounds of ball at each broadside, or 4480 pounds from the whole.

The Ohio is, as far as I am a judge, the perfection of a ship of the line. But in every class you cannot but admire the superiority of the models and workmanship. The dock-yards in America are small, and not equal at present to what may eventually be required, but they have land to add to them if necessary. There certainly is no necessity for such establishments or such store-houses as we have, as their timber and hemp are at hand when required; but they ate very deficient both in dry and wet docks. Properly speaking, they have no great naval depot. This arises from the jealous feeling existing between the several states. A bill brought into Congress to expend so many thousand dollars upon the dock-yard at Boston, in Massachusetts, would be immediately opposed by the state of New York, and an amendment proposed to transfer the works intended to their dock-yard at Brooklyn. The other states which possess dock-yards would also assert their right, and thus they will all fight for their respective establishments until the bill is lost, and the bone of contention falls to the ground.

The sheet-anchor, made at Washington, weighs 11,660 pounds

Main-topsail contains 1,531 yards.

The number of yards of canvass for one suit of sails is 18,341, and for bags, hammocks, boat-sails, awnings, etcetera, 14,624; total 32,965 yards.

The Americans considered that in the Pennsylvania they possessed the largest vessel in the world, but this is a great mistake; one of the Sultan’s three-deckers is larger. Below are the dimensions of the Queen, lately launched at Portsmouth

Note. There are seven navy yards belonging to, and occupied for the use of the United States, viz.—The navy yard at Portsmouth, NH, is situated on an island, contains fifty-eight acres, cost 5,500 dollars.

The navy yard at Charlestown, near Boston, is situated on the north side of Charles river, contains thirty-four acres, and cost 32,214 dollars.

The navy yard at New York is situated on Long Island, opposite New York, contains forty acres, and cost 40,000 dollars.

The navy yard at Philadelphia is situated on the Delaware river, in the district of Southwark, contains eleven acres to low water mark, and cost 27,000 dollars.

It is remarkable that along the whole of the eastern coast of America, from Halifax in Nova Scotia down to Pensacola in the Gulf of Mexico, there is not one good open harbour. The majority of the American harbours are barred at the entrance, so as to preclude a fleet running out and in to manoeuvre at pleasure; indeed, if the tide does not serve, there are few of them in which a line-of-battle ship, hard pressed, could take refuge. A good spacious harbour, easy of access, like that of Halifax in Nova Scotia, is one of the few advantages, perhaps the only natural advantage, wanting in the United States.

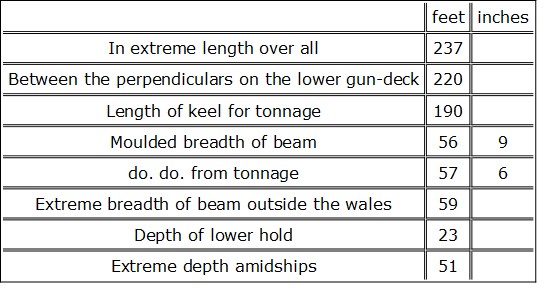

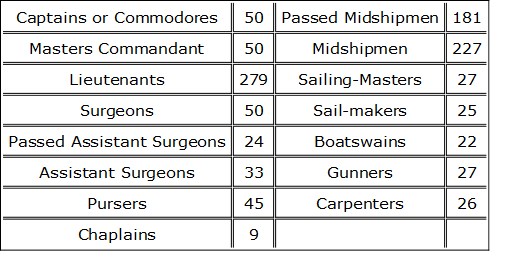

The American navy list is as follows:—

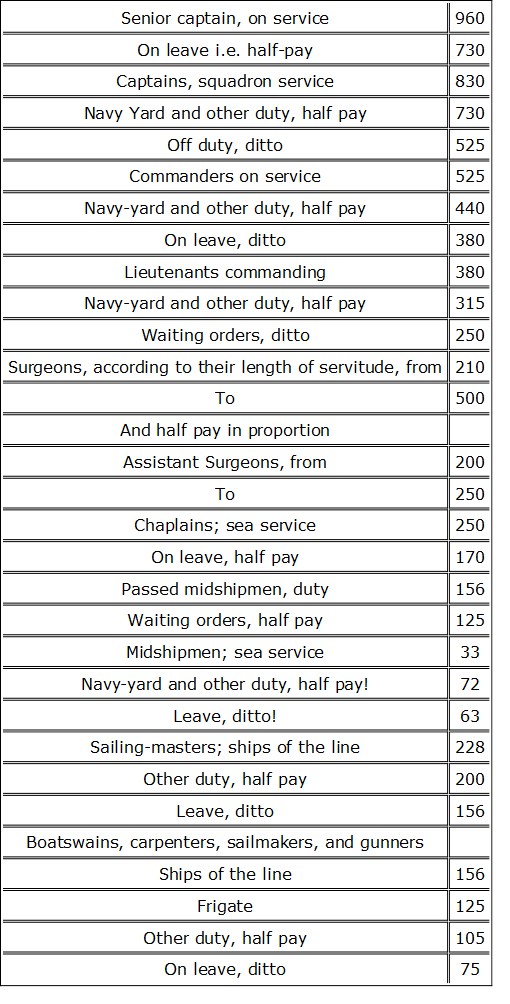

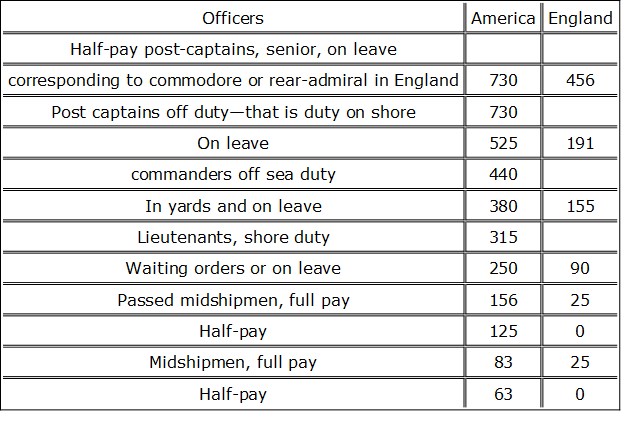

The pay of these officers is on the following scale. It must be observed, that they do not use the term “half pay;” but when unemployed the officers are either attached to the various dockyards or on leave. I have reduced the sums paid into English money, that they may be better understood by the reader:

The navy yard at Washington, in the district of Columbia, is situated on the eastern branch of the Potomac, contains thirty-seven acres, and cost 4,000 dollars. In this yard are made all the anchors, cables, blocks, and almost all things requisite for the use of the navy of the United States.

The navy-yard at Portsmouth, near Norfolk in Virginia, is situated on the south branch of Elizabeth river contains sixteen acres, and cost 13,000 dollars.

There is also a navy-yard at Pensacola in Florida, which is merely used for repairing ships on the West India station.

It will be perceived by the above list how very much better all classes in the American service are paid in comparison with those in our service. But let it not be supposed that this liberality is a matter of choice on the part of the American government; on the contrary, it is one of necessity. There never was, nor never will be, anything like liberality under a democratic form of government. The navy is a favourite service, it is true, but the officers of the American navy have not one cent more than they are entitled to, or than they absolutely require. In a country like America, where any one may by industry, in a few years, become an independent, if not a wealthy man, it would be impossible for the government to procure officers if they were not tolerably paid; no parents would permit their children to enter the service unless they were enabled by their allowances to keep up a respectable appearance; and in America everything, to the annuitant or person not making money, but living upon his income, is much dearer than with us. The government, therefore, are obliged to pay them, or young men would not embark in the profession; for it is not in America as it is with us, where every department is filled up, and no room is left for those who would crowd in; so that in the eagerness to obtain respectable employment, emolument becomes a secondary consideration. It may, however, be worth while to put in juxtaposition the half-pay paid to officers of corresponding ranks in the two navies of England and America:

My object in making the comparison between the two services is not to gratify an invidious feeling. More expensive as living in America certainly is, still the disproportion is such as must create surprise; and if it requires such a sum for an American officer to support himself in a creditable and gentlemanlike manner, what can be expected from the English officer with his miserable pittance, which is totally inadequate to his rank and station! Notwithstanding which, our officers do keep up their appearance as gentlemen, and those who have no half pay are obliged to support themselves. And I point this out, that when Mr Hume and other gentlemen clamour against the expense of our naval force, they may not be ignorant of one fact, which is, that not only on half-pay, but when on active service, a moiety at least of the expenses necessarily incurred by our officers to support themselves according to their rank, to entertain, and to keep their ships in proper order, is, three times out of four, paid out of their own pockets, or those of their relatives; and that is always done without complaint, as long as they are not checked in their legitimate claims to promotion.

In the course of this employment in the Mediterranean, one of our captains was at Palermo. The American commodore was there at the time, and the latter gave most sumptuous balls and entertainments. Being very intimate with each other, our English captain said to him one day, “I cannot imagine how you can afford to give such parties; I only know that I cannot; my year’s pay would be all exhausted in a fortnight.” “My dear fellow,” replied the American commodore, “do you suppose, that I am so foolish as to go to such an expense, or to spend my pay in this manner; I have nothing to do with them except to give them. My purser provides everything, and keeps a regular account, which I sign as correct, and send home to government, which defrays the whole expenses, under the head of conciliation money.” I do not mean to say that this is requisite in our service: but still it is not fair to refuse to provide us with paint and other articles, such as leather, etcetera, necessary to fit out our ships; thus, either compelling us to pay for them out of our own pockets, or allowing the vessels under our command to look like anything but men-of-war, and to be styled, very truly, a disgrace to the service. Yet such is the well-known fact. And I am informed that the reason why our admiralty will not permit these necessary stores to be supplied is that, as one of the lords of the admiralty was known to say, “if we do not provide them, the captains most assuredly will, therefore let us save the government the expense.”