Полная версия

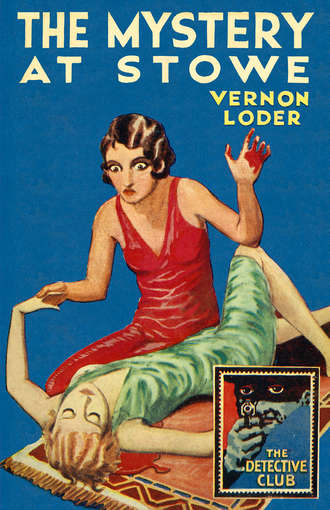

The Mystery at Stowe

That this should happen was troubling enough of itself to the good host and kindly friend, but in addition he had a liking for Mrs Tollard. It may have been that her rather pathetic face and air appealed to him; or her habit of speaking to him as if he stood in some protective relation to her. At all events he felt her death deeply.

He was sorry for Tollard too. The man had not seemed very happy of late. Probably there had been some slight marital differences, but these things fade away in the face of death. Ned would be horrified when he learned what had happened.

It was as well that most of the guests slept well that morning. One or two may have heard the doctor’s car drive up, but at that early hour no one thought anything of it. Mr Barley, in a fret of impatience, let the doctor in, asking him to be as quiet as he could.

‘A good many guests,’ he added anxiously.

‘I see,’ said Browne, in a quiet voice. ‘Will you lead the way, Mr Barley.’

Barley took him upstairs. In the passage near the door of Mrs Tollard’s room, Elaine Gurdon stood waiting. Barley whispered an introduction, Browne bowed, looked curiously at Elaine, whom he had heard lecture, and waited till Mr Barley had unlocked the door.

He advanced into the room, and bent down to look at the dead woman. Mr Barley stopped near him, his heavy face quivering. Elaine slipped in, but remained near the door, her face intent.

Dr Browne pursed his lips, studying the face of Mrs Tollard carefully. Something he saw in it seemed to check him in an impulse to lift the body.

‘Just a moment,’ he whispered over his shoulder to Mr Barley.

Mr Barley stepped gingerly over to him, and listened to a few rapid words that Elaine could not catch. But, watching the doctor’s moving lips, she thought she saw them shape the word ‘Poison.’

‘Yes, we had better wait for the sergeant,’ replied Mr Barley.

Through the open window they heard a slight crunch of loose gravel. The doctor stepped over, glanced out, and nodded back at the others. Barley took this gesture to mean that the police sergeant had arrived on his bicycle. He left the room softly, but hurriedly.

Browne looked at Miss Gurdon. She approached him, and put a question in a low voice.

‘What do you think? She was not very well yesterday.’

He shrugged. ‘I prefer to say nothing for the moment.’

She nodded, and went back to where she had stood before. In a very short time Mr Barley ushered in the sergeant, who tried to cover his excitement by looking very grim and important. This sort of case had not come into his hands before.

He and the doctor spoke together in whispers for a few moments. Then, between them, they raised the dead woman into a sitting position, supported by their arms, being careful not to disturb the position of the lower portion of the body.

As they raised her, Dr Browne removed one arm suddenly, and glanced at the sergeant. ‘Something here,’ he said softly. ‘Can you hold her yourself for a moment, sergeant? I felt something against my sleeve.’

The sergeant did as he was bid. Mr Barley stared eagerly at the two men. Elaine drew herself up, and seemed to be frozen by some sudden thought.

Browne put a hand to a spot beneath Mrs Tollard’s left shoulder-blade, made a gentle plucking movement, and stared at something he held between his fingers. It looked to the others like a dark wooden sliver, or long thorn. The sergeant opened his mouth, restrained an exclamation, and fixed his eyes on this strange object.

‘Lay her back again, please,’ said Browne, his voice troubled.

The sergeant complied. Browne rose to his feet, and approached Mr Barley.

‘If you will leave the room, and Miss Gurdon too, please, I will make an examination,’ he said.

‘But what is it?’ stammered Barley.

‘I am unable to say yet,’ said the doctor.

Mr Barley, greatly shaken, advanced to Elaine, and told her that they must both retire. She nodded absently, and went out with him. The door was shut.

He turned to her when they were in the passage. ‘Will you come down to the library, Miss Gurdon? We can’t talk up here. There has been enough noise already.’

‘All right,’ she said. ‘But, if I were you, I should telephone to the superintendent at Elterham as well. The sergeant does not impress me.’

‘And to Tollard,’ he assented. ‘Dear me! Dear me! This is indeed a tragedy.’

He went downstairs to the telephone, and Elaine to the library. If it struck her as odd that the elderly and experienced business man’s nervousness contrasted unfavourably with her own poise and practicality, she bestowed no further thought on it.

She was sitting smoking a cigarette when Mr Barley returned.

‘I couldn’t get Tollard at his house,’ he said, ‘but the superintendent is coming at once.’

‘Good,’ said Elaine, ‘the sooner the better.’

He took his favourite attitude before the fireplace, and now his coat-tails positively swung like leaves in a gale.

‘I believe that Browne has discovered something terrible,’ he said. ‘He found something. It may have been some species of weapon, though it was very small.’

‘I had a glimpse of it,’ agreed Elaine.

‘It looked like a splinter, or a long thorn,’ he said.

Elaine did not reply for a few moments. She appeared to be thinking quickly, trying to come to some decision. Then she looked him full in the face, and made an observation.

‘I thought I recognised it. But we can make sure very easily. If I am not mistaken, you put up a trophy of some of my curios in the hall. We’ll have a look at it now.’

He gave her a puzzled look, then nodded. ‘I don’t know what you mean, but we can go there if you think it will help us.’

She rose, threw her cigarette into the grate, and preceded him into the hall.

On one of the walls, at a considerable height from the ground, hung a small trophy of South American Indian arms. Chief among them was a blow-pipe and a little receptacle for darts.

‘Get a step-ladder,’ said Elaine, as he came behind her, and followed her glance upwards.

He stood still for a moment, his brows knotted, then went off. When he came back with a light step-ladder he had got in the kitchen, he began to adjust it.

‘Lucky the servants have their own stairs,’ he said in a low voice. ‘I have asked them not to begin cleaning in this part of the house till I tell them. Grover was just coming down when I stopped him.’

She nodded assent, placed the step-ladder near the wall and mounted it before he could, stop her. With a quick hand she detached the miniature quiver for darts, and brought it down.

‘There were six, weren’t there?’ she asked.

He gaped, beginning to see her point, then nodded vigorously. ‘Yes. But surely—’

She took out the darts from the receptacle with the utmost care. ‘I really ought not to have let you have these,’ she murmured, ‘but it can’t be helped now.’

‘There are only five,’ he said, staring at the venomous things in her hand.

She nodded grimly. ‘Just five. Now we know where we are.’

Mr Barley’s eyes grew wide with horror. ‘Then you think that thing upstairs—?’ he began.

‘I am sure of it,’ said Elaine.

‘But they were not poisoned surely?’ he gasped. ‘The other day, you know, you showed us how that pipe was used.’

Elaine nodded. ‘The chief from whom I got those had a couple of dozen made for me. The poisoning is a later operation. Naturally, I used harmless darts.’

‘Good heavens!’ he cried, ‘is that what you meant about the window being open?’

She nodded. ‘I have seen people shot with those poisoned darts. Something in her face reminded me. But wasn’t that a door opening upstairs?’

He left her, and went upstairs. He returned in a few minutes, followed by the doctor and the police sergeant. Elaine had removed the step-ladder by that time, and was standing near the door of the library. Mr Barley opened that door, let the two men in, and signalled to Elaine to accompany them.

‘Sit down, gentlemen,’ he said, when he had closed the door. ‘Please sit down too, Miss Gurdon.’

They sat down. Dr Browne looked at Elaine, and then at Mr Barley. ‘Well, Mr Barley, I am sorry to say that my conjecture was only too true. An alkaloid poison seems to have been the cause of death, and I have no doubt it had been placed on the point of the little sliver of wood I found implanted just under the left scapula, the shoulder-blade of your unfortunate guest.’

Mr Barley shot a glance at Elaine. ‘I have telephoned for the superintendent at Elterham. He is coming. Perhaps we had better wait for him before we go any further.’

Dr Browne shrugged. The sergeant nodded. ‘Very well, sir, that might be best. But perhaps I could make a few notes now.’

‘Most of my guests are still abed.’

‘I suppose so, sir; but you might tell me how you came to know something was amiss.’

‘That, of course, I can do,’ said Mr Barley, and coughed nervously. ‘After that, if you will both be good enough to remain in this room for a while, I shall have breakfast sent into you. You see, I have the guests to consider. I should prefer not to alarm them now, but to inform them of the tragic event when they have breakfasted. They will then be at your disposal.’

Browne shrugged. The sergeant nodded again. Mr Barley went on: ‘As for myself, I heard a curious noise a little while ago. It seemed like a sound made by someone in pain. It was followed by what seemed a dull thud. I got up hurriedly to dress, when I heard a knock on my door.’

The policeman noted that down. ‘Yes, sir?’

‘It was Miss Gurdon, who had come to tell me that Mrs Tollard was dying, or dead. It appears she had heard the sound, and gone in to see what was the matter.’

The doctor and the sergeant turned their eyes quickly on Elaine Gurdon. She nodded, her eyes anxious, but not afraid.

CHAPTER IV

A CURIOUS THING

ELAINE GURDON’S aplomb had been the admiration of her friend. It had never been more apparent than now.

‘Don’t you think, on the whole, it would be wiser to—to allow the superintendent to hear my statement?’ she asked, in a low but clear voice. ‘It will save going over it twice. I did, of course, find Mrs Tollard dead, as Mr Barley says, but any light I may be able to throw on it may be better exhibited to your chief, sergeant.’

He plucked at his lip uncertainly. He was not very sure of his powers in a case like this, and it was unlikely in the end that the detective force in Elterham would allow him to take the thing up.

‘As you please, Miss,’ he said.

Mr Barley seemed about to say something; perhaps with reference to the darts, but a glance from Elaine stopped him. This glance was not noticed by the sergeant, who was putting away, his note-book, but it did not escape the doctor’s eye.

In the end, it was agreed that breakfast should be sent into the library for the two men, Mr Barley was to inform his guests of the ocurrence after breakfast, and, on the arrival of the superintendent from Elterham, everyone in the house would be questioned as to their knowledge of the facts that might bear on the tragedy, or their (more probable) ignorance of anything throwing a light on it.

Only Dr Browne was slightly dissatisfied. He thought Elaine too calm and self-possessed for the occasion, and he could not forget how, at her lecture, he had seen her exhibit a blow-pipe, and tell her audience that, on occasion, she had shot birds for the pot with this primitive weapon. An idea in his mind that the alkaloid poison which had killed Mrs Tollard might be the well-known woorali, more scientifically known as curare, at once made the connection. There are few doctors who do not know how this poison was first used.

Added to that was her desire to postpone her statement, and the fact that it was she who had found Mrs Tollard dead. It was, it is true, not very obvious why she should prefer to tell her story to the superintendent, but it struck him as rather queer. The sergeant, of course, did not see that. He was a slow-thinking man, who could only get through routine duties.

He and the sergeant breakfasted together, the latter apologetic and ill at ease, until Browne assured him impatiently that he had messed in the trenches next a one-time convict!

Superintendent Fisher was slow in coming. The guests had assembled for breakfast when he came, accompanied by a detective-inspector of the Elterham force. They were shown into the room where the dead woman lay, and Mr Barley set to work with a heavy heart to play the host.

‘Isn’t Mrs Tollard coming down?’ asked Ortho Haine, who had become rather a hero worshipper.

‘No,’ said Mr Barley awkwardly, ‘not now. By the way, Haine, I’d like to hear what you think of my cook’s new way of doing kidneys.’

Someone laughed, the transition was so rapid, but Haine, who was not imaginative, looked at his plate.

‘I thought it was new to me—rather jolly effect, I should say, sir. What do you think, Head?’

‘Quite piquant,’ said Head. ‘We must try this way at home, if your cook will give us the tip.’

So breakfast blundered on. When it was over, and the various guests were on the point of scattering, Mr Barley got up. He was very red in the face, and trembled a little.

‘I have something to say to you all,’ he began. ‘Do you mind following me into the drawing-room? It’s rather—er—important, and, well, I’ll tell you there.’

The guests exchanged startled or amused glances, but followed him to the drawing-room, where they disposed themselves to listen.

Mr Barley opened his mouth, muttered one or two broken sentences, and turned appealingly to Elaine.

‘Will you tell them, Miss Gurdon?’

They all stared with open eyes at Elaine, who rose, and glanced round. Her face was very pale, but her voice was measured and unemotional as she began.

‘A tragic thing has happened,’ she said. ‘Poor Mrs Tollard died last night—or this morning, I should say. Please let me go on. We are afraid that something more is involved. I am sorry for Mr Barley, and sorry for you all, but the police are investigating. They are in the house at this moment. I think that is all Mr Barley wished me to say.’

For a moment there was a dead silence, then an uproar of voices broke out that Mr Barley had the greatest trouble to subdue. The two friends Miss Sayers and Mrs Gailey were in tears, Ortho Haine was demanding to know what had happened. Mr and Mrs Head (not very sure if they had a grievance against Fate or Mr Barley) were debating the question of leaving at once, while old Mrs Minever, without the slightest warrant, was saying that she had always known something would happen.

In all their minds was a general feeling that Elaine’s composed demeanour and clear speech was a sign that she lacked heart. Or, perhaps, that is too sweeping, for Miss Sayers was a champion of Elaine’s, and, when she had dried her eyes, grateful for the latter’s calmness, which had prevented a general attack of hysteria.

Mr Barley looked about him pleadingly. ‘Please, please!’ he begged, ‘I feel it as deeply as any of you. It is most unfortunate that this should have happened in my house, and at this time, when I have you with me. But we must face the fact. In ordinary circumstances I should not attempt to detain you here, but as it is, I must ask you to stay for a little.’

He seemed to have recovered himself again, but the Heads had not.

‘My dear Barley,’ said the husband, ‘I am sure we can be of no use. We—’

Mr Barley raised his hand. ‘It has nothing to do with me. The police will insist on examining all who were in the house at the time of Mrs Tollard’s death. But I am sure it will be more or less formal.’

‘I think Mr Barley is right,’ said Haine. ‘We all ought to help.’

‘Of course,’ said Mrs Gailey quickly.

The Heads at last assented with an ill grace, and Mr Barley told them all briefly what had happened. ‘I shall ask the superintendent to put any questions he has to ask, as soon as possible,’ he ended. ‘It is a very serious matter.’

‘Has anyone wired for Tollard?’ asked Haine.

‘I telephoned early, without result, and I have wired since. Now, if any of you would like to go to your rooms, or do anything in the matter of packing, please do. But you must be ready to come down when the superintendent asks for you.’

The Heads fled upstairs at once. It was a dreadful thought that they might have to go without their bridge for a day or two. They were not really callous people, but unimaginative, and obsessed by cards. Mrs Minever went behind them, full of her prophecies, and Ortho Haine went up to talk to Mr Barley. Elaine disappeared next, and Miss Sayers and Mrs Gailey, arm in arm, sedulously whispering, drifted out into the sunny garden.

‘What does it mean?’ asked Nelly Sayers, when they were out of earshot. ‘It sounds beastly.’

Mrs Gailey nodded. She was very excited, and her eyes shone. ‘Simple enough. Someone evidently hated her, and poisoned her. What a good thing it is Ned Tollard had gone.’

Her companion opened wide eyes. ‘My dear Netta! What do you mean?’

‘Nothing against Ned,’ said the other hastily. ‘Only you know how people talk. I thought Elaine was dreadfully calm. If I had been asked to tell the news, I should have simply blubbered,’ she added.

‘But you aren’t used to speaking in public,’ said her friend. ‘Elaine is. I thought it was fine of her. You could see poor old Barley was simply dithering. In any case, Margery wasn’t her relation. She never cared for her. If you and I were frank, we should say that we weren’t really upset so much by Margery’s death as by the way it was done. I am sorry for the poor soul, but I am sorry for a good many people.’

‘Oh, I liked her. I agree with Ortho that she was very patient and really sweet, though she never said much to me.’

‘Well, it doesn’t matter much now,’ observed Miss Sayers. ‘The thing is, who killed her? I didn’t quite follow what old Barley said about a dart. I don’t think he was very clear, do you?’

‘Oh, I got that part. Don’t you remember a few days ago we were out on the lawn, and he asked Elaine would she show us how the savages fired off those blow-pipes?’

‘Of course I remember.’

‘And she did. Ortho said he never knew a woman could use one, and Ned said he didn’t see why not. Even if it was a question of blowing hard—’

Miss Sayers nodded. ‘He made a joke about women blowing their own trumpets nowadays. I remember—Go on!’

‘Well, she brought out some little darts like thorns, with what looked like a bit of cotton-wool on the end, and hit the cedar with them several times.’

‘But if she had missed, and hit one of us, we might have been poisoned too!’

‘I don’t think she would use that kind. I expect she has some without any poison.’

Miss Sayers nodded gravely. ‘You mean it was one of the poisoned ones they found in poor Margery?’

‘I am sure he meant that. When you said people talked, I thought of that at once.’

‘But why should you, dear?’

‘Well, we know it was Ned’s business with Elaine’s expedition that annoyed Margery.’

‘But surely no one would be so wicked as to suggest—’

‘Oh! wouldn’t they? I don’t know that it is wicked either. The police will fish about for evidence, and a motive, and they will know it was Elaine who had these darts, and knew how to use them, and it was she who found Margery.’

‘But that has nothing to do with it. The finding, I mean. I can tell you, Netta, if the horrid police ask me if I know there was a split between Ned and Margery over Elaine, I shall say I have no idea. I haven’t really. It isn’t fair to decide that they were really divided just because Margery and he looked glum at times.’

‘No, I suppose not,’ said Netta thoughtfully. ‘They want to know facts, not conjectures. I agree with you. I won’t say a word about what I conjectured. Mr Barley said her window was wide open. Some burglar may have shot her from outside. If Elaine had done it, she wouldn’t have been such a fool as to go in to find her dead.’

‘Of course she didn’t do it,’ said Nelly. ‘I am only afraid of Ortho Haine saying something. The Heads are too absorbed in bridge to know what is going on, but Ortho has been quite potty lately about Margery.’

‘You mean he was in love with her?’

‘No, I don’t say that. He’s a nice boy, and I like him, but he has Platonic passions. Last year he used to adore that bad-tempered tennis player; though I don’t believe he ever met her! I am sure he thought Ned too material for Margery.’

‘He is rather an ass,’ said Netta. ‘But perhaps we had better go in again now, and wait for the superintendent.’

The superintendent had already arrived, and was making an investigation of Mrs Tollard’s room, in the company of the detective. As Mrs Gailey and her companion returned to the house, they saw two men momentarily at the window above. Fisher was tall and gaunt, a very grave man with a worried air; the detective-inspector was round and chubby.

‘I suppose they have to measure, and do things like that,’ said Nelly, as she entered the door.

Their evidence was not required at once, and quite half an hour had passed when the two officers from Elterham descended the stairs with Mr Barley, and went into the library. A minute later, Mr Barley emerged, and went for Elaine.

‘They want to hear what you have to say,’ he told her, in his worried voice.

She nodded, and accompanied him. When she entered the library she gave each man in turn a quick, observant look, then sat down, and folded her hands lightly on her lap.

‘I understand that you wished to see me?’ she said.

Superintendent Fisher bowed. ‘Yes, madam. I understand that you were the first to discover the body of the poor lady upstairs. I should like to ask you a few questions.’

‘Very well.’

The inspector had a note-book on his knee. He sucked his pencil-point meditatively, and bent an alert ear.

‘What first attracted your attention to that room?’

Elaine replied clearly, ‘My own room is next to it.’

‘Not the room with the communicating door?’

‘No, that was Mr Tollard’s room. Mine is to the other side. I was rather restless last night, on account of the heat. It was just about dawn when I heard slight movements in the next room. A bed seemed to creak, as if someone were tossing on it.’

‘Surely this is an old house, with thick walls?’

‘I should think it is. But her window was open, and so was mine. At any rate, I heard these sounds. Later on, I heard what sounded like a moan. Mrs Tollard had not been well the day before, and I wondered if she was in pain. At last I got up, went into her room, when I heard a slight cry, and found her lying on the floor, dead.’

‘Did you hear her fall?’

‘No.’

Mr Barley interposed anxiously: ‘Excuse me. I thought I heard a thud, though my room is on the other side of the passage.’

Elaine stared straight before her. ‘When I entered the room, and saw her lying there, I put my arm under her, and tried to lift her up. Then something told me she was dead, and though I have had some experience in my travels of sudden deaths, I was so shocked that I let her fall back.’

‘That will explain the bruise on the back of the head,’ said the superintendent.

CHAPTER V

THE FINGERPRINTS

‘HAS Dr Browne gone?’ asked the superintendent, of Mr Barley.

‘Yes. He had to go to an urgent case. He will be back later.’

‘Then we must leave this question of the bruise till later. Now, Miss Gurdon, you are aware that Dr Browne believed Mrs Tollard died as the result of some alkaloid poison in which the point of a dart had been steeped. You know something of these primitive South American weapons.’

‘Yes.’