Полная версия

The Mystery at Stowe

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1928

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd 1929

Introduction © Nigel Moss 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2016

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137489

Ebook Edition © March 2016 ISBN: 9780008137496

Version: 2015-11-24

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Editor’s Preface

Chapter I: Wheels Within Wheels

Chapter II: What the Morning Brought

Chapter III: The Dressing-Gown

Chapter IV: A Curious Thing

Chapter V: The Fingerprints

Chapter VI: Fisher Lays a Trap

Chapter VII: A Stranger in Red

Chapter VIII: Mr Carton Intrudes

Chapter IX: The Husband

Chapter X: Did Tollard Love His Wife?

Chapter XI: Suppressions

Chapter XII: Carton Is Dissatisfied

Chapter XIII: Who Was It?

Chapter XIV: An Open Mind

Chapter XV: The Eyes of Mr Jorkins

Chapter XVI: The Scratch

Chapter XVII: Tollard Makes a Scene

Chapter XVIII: The Dart

Chapter XIX: The Locked Door

Chapter XX: Speculations of a Kind

Chapter XXI: The Ladder

Chapter XXII: The Arrow That Flyeth by Night

Chapter XXIII: A Bit of Fluff

Chapter XXIV: Elaine Is Stubborn

Chapter XXV: Carton V. Tollard

Chapter XXVI: Superintendent Fisher Wants the Ladder

Chapter XXVII: The Luck of the Ladder

Chapter XXVIII: The Brooding Silence

Chapter XXIX: A Joint Expedition

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

THE Golden Age of detective fiction is enjoying a renaissance in popularity, demonstrated by the success of various publishing ventures. The British Library Classic Crime series has reissued works by obscure Golden Age authors, such as John Bude, J. Jefferson Farjeon and Alan Melville, with Farjeon’s Mystery in White the surprise best-selling paperback of Christmas 2014. HarperCollins’ major non-fiction study The Golden Age of Murder by Martin Edwards (May 2015) sold out its first printing within a few months, and their new editions of titles from the Detective Story Club, which first flourished back in 1929, are reintroducing a range of once hugely popular crime authors. Along with a number of small independent publishers, notably Black Heath, Coachwhip, Dean Street, Faber, Ostara and The Murder Room, coupled with the rapid growth in modestly priced e-books, these initiatives have led to the emergence of a new and appreciative modern audience for little-known and neglected Golden Age authors who have long been out of print.

The period between the two World Wars, which Robert Graves called ‘the long week-end’, loosely delineates the boundaries of the Golden Age. From 1919 to 1939, detective novels were published in an ever-increasing tide to keep up with a growing public demand for ‘whodunits’. They were a reflection of the atmosphere and culture prevailing during that period. There was a strong desire to sublimate the horrors and devastating impact of the First World War, which had been followed by the Spanish flu pandemic, economic hardship (including the Great Depression), and later by an increasing international turbulence and prospect of yet further conflict. In response, people turned more and more to entertainment and escapism, and the new form of detective novel fitted the bill. Human activity, including murder, was described and analysed as a form of play or game—an artificial entertainment existing in a cosy, stylised world, removed from normal routine life. This literary game devised its own distinctive rules and conventions aimed at ensuring fair play between writer and reader. The focus was predominantly on producing stimulating intellectual puzzles and plots: clues and evidence were presented to the reader, with a challenge to solve the mystery before the denouement and the detective’s masterful unveiling of the guilty party. It offered a welcome form of inward escape.

Typically, the atmosphere of these novels was brisk and business-like, the method of murder often bizarre. Characterisation was subordinate to the plot. Readers were not required to think too deeply or moralise, and psychology was largely absent. The actual commission of murder, with its violence and revulsion, was usually excluded from the narration. But this was not reality, rather an intellectual recreation. Margery Allingham commented on the form: ‘a Killing, a Mystery, an Enquiry and a Conclusion with an element of satisfaction in it.’ It was claimed these novels, with their rationalistic plots and cleverly crafted puzzles, helped to ‘improve the mind’. A surprisingly high proportion of professional people and academics were among the readers, including British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Detective fiction of this era attained a high degree of respectability amongst the reading public on both sides of the Atlantic, and by 1939 detective novels accounted for 25 per cent of all new fiction published in English.

The distractions and pressures of today’s world, with extreme violence and hardship forming commonplace daily images in both mainstream and social media, along with the persistent noir psychological themes and human depravity depicted in modern crime novels, have perhaps helped to rekindle the public’s affection and enthusiasm for the Golden Age fictional world of intellectual plots and puzzles. Now, as then, at heart they offer light entertainment—an enduring appeal of solidity blended with facetious frivolity.

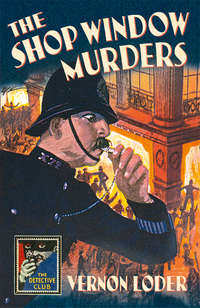

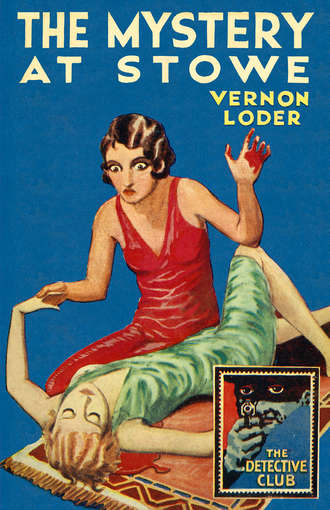

Vernon Loder was among the early wave of Golden Age writers. A popular and prolific author, he wrote 22 titles during the decade immediately preceding the Second World War. The Mystery at Stowe was Loder’s first work, initially published in 1928 by Collins as a full-priced novel, and reissued the following year in their popular and eye-catching new sixpenny crime list, The Detective Story Club.

In the original Preface to this reissue of The Mystery at Stowe, the Club’s editor, F. T. (Fred) Smith described Vernon Loder as ‘one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers’. While Loder was a firm believer that the task of the detective fiction writer was not only to mystify but to entertain, he realised that the key essential for success was brilliant detective work and made this the chief feature of the story. The setting is a traditional country house party, favoured by Golden Age writers and one to which Loder returned in several later novels. The action features a diverse group of party guests, and takes place mostly within Stowe House and its grounds. One of the guests is found dead in her bedroom at dawn, lying beside an open window. She had been killed by a small poisoned dart, found lodged in her upper back. Amateur sleuth Jim Carton is in the mould of the new breed of ‘hero’ detectives, arguably first modelled by E. C. Bentley’s creation Philip Trent—intelligent and engaging, yet modest, sensitive and fallible. He brings the added expertise of having once been an Assistant Commissioner in West Africa, where he had investigated numerous criminal cases, and gained knowledge of the natives’ subtle use of little-known poisons in committing murder using a blow-pipe and poisoned darts.

Whereas Loder’s murder method had also featured a couple of years earlier in Edgar Wallace’s The Three Just Men (1926), his mystery is intriguingly plotted and seemingly impenetrable, and red herrings and blind alleys abound. With twists and turns throughout, excitement and tension steadily mount, with a denouement true to Golden Age conventions. The finale is truly surprising and revelatory. One reviewer has described the solution as ‘borderline genius yet utterly insane’ (John F. Norris—Pretty Sinister blogspot, April 2013).

Stowe is a well-written and skilfully constructed story, which blends action, detection, human interest and romance to form a varied and effective first mystery novel. It also contains some witty dialogue and observations, with Loder’s use of names and places which nod to other Golden Age writers and novels of the same period an amusing feature for genre enthusiasts.

Vernon Loder was one of several pseudonyms used by the hugely versatile and fecund Anglo-Irish author Jack Vahey (John George Hazlette Vahey), 1881–1938. In addition to the canon of Loder titles between 1928 and 1938, Vahey wrote initially as John Haslette from 1909 to 1916, resuming writing in the late 1920s as Anthony Lang, George Varney, John Mowbray, Walter Proudfoot and Henrietta Clandon. Born in Belfast, Jack Vahey was educated in Ulster and for a while in Hanover, Germany. He began his working life as an architect’s pupil, but after four years switched careers and sat professional examinations with a view to becoming a chartered accountant. However, this too was abandoned, when Vahey took up writing fiction. He married Gertrude Crewe, and settled in the English south coast town of Bournemouth. His writing career was cut short by his death at the relatively young age of 57.

All of the Loder novels were published by Collins in the UK. From 1930 onwards, his works were published under their famous Crime Club imprint. Several of his early novels (between 1929 and 1931) were also published in the US by Morrow, sometimes under different titles. Loder had several series detectives—Inspector Brews, Chief Inspector Chase and later Donald Cairn—but Jim Carton makes his sole appearance in Stowe. The publisher’s biographical note on Loder which appears in Two Dead (1934) mentions that his initial attempt at writing a novel (apparently never published) was during a period of convalescence in bed. Various colourful claims are made of Loder: he once wrote a novel on a boarding-house table in twenty days, which was serialised in both England and the US under different names, and published in book form in both countries; he worked very quickly, and thought two hours in the morning quite enough for anyone; also, he composed directly on a typewriter, and did not ever re-write.

Loder’s entertaining and skilful novels are written in the simple, direct, smooth-flowing and occasionally jocular style favoured by Golden Age authors. His hallmark distinctives include complex and ingenious plots, full of creativity and invention, leading up to a major surprise and twist in the closing pages. A recurring theme often found in his works is that of the victim who falls prey to his own scheming. Despite his early popularity, Loder never quite achieved the first rank of detective novelists and the enduring status and fame which accompanies this, although original Collins jackets demonstrate that he was well-reviewed: ‘The name of Mr Loder must be widely known as a reliable and promising indication on the cover of a detective story’ (Times Literary Supplement); ‘Successive books by Vernon Loder confirm the impression gathered by this reviewer that we have no better writer of thrill mystery in England’ (Sunday Mercury); ‘…just the effortless telling of a good story and meticulous observation of the rules’ (Torquemada in the Observer). Nevertheless, his works have remained out of print since the 1930s, and have been the purview of Golden Age collectors, among whom he has a dedicated following, with first editions scarce and commanding high prices.

Now Vernon Loder is emerging from obscurity—and rightly so. Despite the rather scant and cursory attention he has received in the major detective fiction commentaries, Loder has a number of proponents, including leading US writers on Golden Age fiction, John Norris and Curtis Evans, and deserves a better place in Golden Age posterity. I particularly recommend searching out some of his later titles—Whose Hand (1929), The Vase Mystery (1929), The Shop Window Murders (1930), Death in the Thicket (1932) and Murder from Three Angles (1934). Loder deserves to be rediscovered and enjoyed by a new readership, and this reissue of his important first novel The Mystery at Stowe augurs well for the revival of his popularity.

NIGEL MOSS

October 2015

EDITOR’S PREFACE

MR Vernon Loder is one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers, and this novel The Mystery at Stowe augurs well for his future popularity. He certainly knows how to provide a mystery baffling enough to satisfy the most exacting reader. He holds too a very definite opinion, with which we are wholeheartedly in agreement, that the task of the writer of mystery stories is not only to mystify, but to entertain. Consequently he has enlivened the more serious business of detection by the inclusion of several amusing characters.

But while appreciating to the full the entertainment value of the thriller, Mr Vernon Loder fully realises that nothing succeeds so well as really brilliant detective work, and that is the chief feature of his story. The reader may justly suspect every character of the murder of Mrs Tollard in that pleasant country house, and interest and suspense are cleverly maintained to the very last, when a well-engineered surprise awaits us. Jim Carton himself is a most interesting detective to follow. He is an unusual type and brings to the problem the fresh and alert mind of an Assistant Commissioner in West Africa. In that capacity he has investigated many criminal cases among natives. The fact that a tiny poisoned dart was found buried in the victim’s back specially interests one who has special knowledge of African natives and their subtle use of little-known poisons in committing murder.

His experience had led him to support a theory that there were five primary motives for murder—anger, jealousy, greed, robbery and hate—and this test he applies in turn to the suspects in order to discover that most baffling thing in a murder case: a motive. Who? How? Why? These are questions which confront Jim Carton—and our readers.

THE EDITOR

FROM THE ORIGINAL DETECTIVE STORY CLUB EDITION

November 1929

CHAPTER I

WHEELS WITHIN WHEELS

‘NED is full of vitality, and Margery hasn’t a backbone even the X-rays could detect,’ said Mrs Gailey, as she chalked her cue, and leaned over to take her shot. ‘That’s the trouble, I am sure, and if it wasn’t for (Oh! rotten miss! I put on far too much side)—I mean to say only for her sweet temper, there would have been a dog-fight before this.’

Mrs Gailey, a vivacious brunette of about twenty-six, was known to be summary in her judgments, and better at jumping to conclusions than negotiating fences in the hunting-field. Miss Sayers, with whom she was playing in the billiard-room at Stowe, strolled round the table to where her ball lay, her face wearing an expression of mild scepticism.

‘I don’t see why there should be a quarrel, and I can’t quite agree with you that she has a sweet temper,’ she remarked. ‘By the way, Netta, you’ve left me in a perfectly beastly lie under the cushion.’

She stabbed at the ball, and, by a marvellous fluke, effected a cannon. Mrs Gailey applauded ironically.

‘I never heard her say a cross word in my life,’ she observed.

Nelly Sayers played a losing hazard, and looked up when her ball rolled gently into the pocket. ‘That doesn’t prove anything either way. I don’t say she has a bad temper. I only say we can’t call it sweet till we know.’

‘Wait till you’re married,’ said Mrs Gailey, with a wise look, ‘you get different ideas of life.’

‘I expect you do. You married people think we are a positive danger to your dear husbands. We have even to be careful where we smile.’

‘You may smile at mine, when he comes down,’ said her companion, laughing, ‘but there is something in what you say. Margery is one of us, and we’re bound to look on Elaine Gurdon as a poacher.’

Nelly Sayers foozled an easy pot, and came round. ‘That strikes me as awfully silly. It isn’t Elaine’s fault that she is handsome, any more than it is yours.’

‘A thousand thanks,’ smiled Mrs Gailey, looking at her ball. ‘Go on! I like to hear that sort of thing.’

‘At any rate, she is jolly good-looking, and she has seen things and done things I should have funked.’

‘But she has no nerves, and she enjoys it. She wouldn’t be happy living all the year round in civilisation. If you enjoy anything there is no hardship in it.’

Miss Sayers sat down on the bank. ‘I don’t say there is. What I mean is this. She travels in all sorts of wild places, and has made one or two discoveries. But she hasn’t the cash to go on.’

‘I thought she wrote books?’

‘So she does, but I suppose they don’t make enough to keep her, and cover the expenses of travel as well.’

While she spoke, Mrs Gailey made twelve, and glanced up with a smile at the scoring-board, where apparently she only needed fifteen more for game.

‘She might go to her bank for it.’

Nelly Sayers shrugged. ‘Banks aren’t too generous. In any case, Ned Tollard is only financing her expedition for the fun of the thing. He’s interested in South America. Isn’t he a director of the Paraguayan railway?’

‘I don’t know. I suppose so. But it sounds odd, and I know, if my husband spent half the day consulting a woman like Elaine Gurdon about maps and routes, and things of that kind, I should feel pretty hot about it. That’s why I say she has a sweet temper. She never says a word, but sometimes I have caught her looking at Ned in a sad way.’

Nelly Sayers made six, and broke down. Mrs Gailey took her cue, deciding to risk the pot which would take her out.

‘I expect she is like me. She doesn’t think there is much in it.’

‘Perhaps not. Oh! I’ve done it. That makes game, and I’m going into the garden. Coming?’

‘No, thanks, I must write a letter.’

The house of Stowe, at which they were both staying for a week, had once belonged to a family more noted for warlike fame than wealth. Unlike the builders of the famous house of the same name, they never rose to be great lords or mighty men in the world. Stowe itself was really a very large manor-house, and the family had only parted with it in the nineties, when it had passed into the hands of Mr Magus, a miser and recluse, on whose death it had been sold to the present occupier, Mr Barley.

Mr Barley was fat, and fat-pursed. Rumour had it that he was extremely vulgar, but he was in reality a good-natured man who had not enjoyed a decent education, and was well aware of it. By sedulous cultivation he had picked up all his aitches, and learned to swallow those unnecessary ones that occasionally rose to his lips. He liked society, and though he never ranged in the higher branches, he was able to fill his house with decent people of the upper middle-classes, who could enjoy his hospitality without feeling or showing too open scorn for the humble upbringing of their host. Some of the younger guests did indeed call him ‘Old Barley,’ but most of them liked him, and some were not averse from accepting the tips he gave them with regard to finance.

At the moment when Mrs Gailey and Miss Sayers were playing a game of billiards, the house had only a few guests. Chief among them was Elaine Gurdon. Single, handsome, known as the heroine of an expedition into the wilds of Patagonia, and an enterprise which had penetrated the Chaco, she was sufficiently famous to secure a pretty regular place in the photographic galleries of the illustrated weeklies, and the chairmanship of gatherings at women’s clubs, when travel was the topic.

Associated with her, occasionally in scandal of an ill-natured kind, which had originated in his offer to finance her next trip, was Edward Tollard. He was thirty years of age, a vital, good-looking fellow, fond of exercise and all open-air sports, and a junior partner in a banking firm. He came of a family that had enjoyed money for several generations, a kin that was neither bookish nor artistic, and his marriage, three years before, to Margery the daughter of Gellis, the impressionist artist, had surprised most of his friends.

Those who set store by Old Masters said that Margery was a Botticelli come to life; others said she had never really come to life at all. She was pretty, in a pale way, with very fair hair, blue eyes, a sensitive mouth, a long oval face. She looked excessively fragile, though she was rarely ill, and was in every way a strong contrast to her athletic husband.

There were also in the house, the two billiard players; a Mr and Mrs Head, who were inseparable, and had only one thought between them—bridge. Last came Ortho Haine, a young fellow who was much nicer than his unusual Christian name; and a little old lady reputed cousin to Mr Barley, called Minever. Mrs Gailey’s husband was coming down for the week-end with several other people.

It is perhaps the fate of Botticellis come to life to look reproachful in a gentle way. That set of countenance in Margery Tollard, combined with the fact that her husband was proposing to finance Elaine Gurdon’s next trip into the wilds, had given rise to gossip.

Margery did not hunt, or go out with the guns in the season; she did not care for walking, or yachting, or games. Her function in life was ornamental. She pleased the artists, and made sportsmen furious. This necessarily made a kind of breach between her and her husband, not an open breach it seemed. But, as he needed exercise and enjoyed it, there were a good many days when they were apart.

People said he was indulgent enough, would even accompany her to private views, where the pictures must have made him bite his tongue; to artistic functions, of a social kind, where he looked like a healthy tree among sickly saplings.