Полная версия

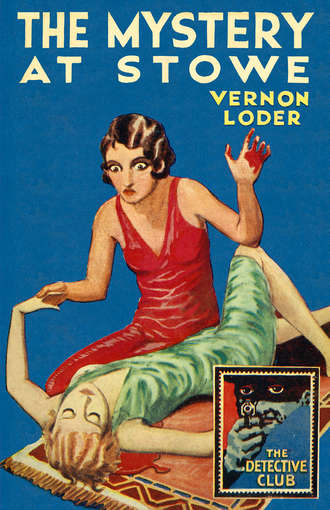

The Mystery at Stowe

Then Elaine came back from her last pilgrimage, full of new plans. He had known her since she was a mere school-girl. He was interested in exploration, and in the country she had visited. He discussed the next trip with great interest, and, hearing that its success depended on finance, offered to help.

She had written a book, and was giving a series of lectures. If the proceeds of both left a deficit on the sum needed for the future, he was to make it up. Margery objected. She did not tell her friends, but she objected very much even to a Platonic partnership between her husband and the explorer.

Elaine Gurdon instinctively felt this trouble. She knew Margery, and never failed to call to see her when she was in town. They were at opposite poles in thought and action. Margery disliked her; Elaine had sometimes an impulse to shake the pale, shadowy, young woman she felt to be such a drag on Ned Tollard.

‘If she even made an effort, I could forgive her,’ she had told Nelly Sayers, ‘but she won’t move. She’s the most selfish woman I know.’

That was indiscreet, but she was a woman who spoke out on occasion, and Nelly laughed.

‘She certainly might buck up.’

The projected expedition was one to the hinterland of Matta Grosso, and as it was planned out, the expenses necessary to success seemed to mount daily. Elaine confessed that she would need five thousand more than her book and her lectures were likely to earn, and Tollard was willing to give that sum. But, first, they went into it together, to see where expenses could be cut down. Elaine insisted on that.

‘I haven’t much of a business brain, Ned,’ she said to him. ‘I know what I might spend, but I don’t know what I need not. Then I want your advice about the route. I could cut out the last bit of the trip if necessary.’

At first it was decided that the consultations should take place at his house, but that was not a success. Margery was a sulky third, visibly impatient with their consultations, and ended by suggesting to her husband that they might be held elsewhere.

Mr Barley, having never been out of England in his life, had a fancy to be a patron of some foreign enterprise which should bring him into the public eye. He had heard some of the prevalent gossip, and asked Elaine down to stay with him, with two motives. She was lecturing at Elterham, and he had to be chairman. He had asked her as a favour to bring with her some of the many curios she had acquired in the trip through the Chaco, good-naturedly saying that he might be disposed to invest in some of the rarer objects for the adornment of his hall and library.

It was in part his second motive, an altruistic one, that had led him to invite Margery and Ned Tollard at the same time. A bachelor himself, he hated to see married people uncomfortable, or at loggerheads, and was preparing a plan to ease what he had heard was the tension in Tollard’s menage.

Just about the moment when Mrs Gailey went out into the garden, and Miss Sayers went up to her room to write a letter, he intercepted Elaine Gurdon in the hall.

‘Tollard gone out, Miss Gurdon?’ he asked, beaming on her in his fat way, ‘or have you another consultation on?’

She returned his smile. ‘I think he and Margery drove over to Elterham. She wanted to order some book.’

‘Good. Then I can annex you, Miss Gurdon, and have a little chat, if you don’t mind.’

‘Not a bit,’ she said, her brown eyes twinkling, ‘I am becoming quite a good saleswoman, you see. But, really, I find you are not such a shrewd buyer as I imagined.’

‘I don’t bring that home here,’ he said, opening a door off the hall. ‘Come along into the library, and have a cigarette with me. I have a little scheme I have been worrying out, and I’d like to hear what you think of it.’

She followed him, and he drew forward a comfortable chair for her, then closed the door, and came to stand with his hands behind his back in front of the empty fire-place.

‘Now those curios I bought from, you are most interesting,’ he began, when he had seen that her cigarette was alight. ‘They mean a lot more to me than to you, for I never had the chance to go abroad when I was young, and I am too old for it now. It’s a great thing that you can get about to all these strange places, and extend our knowledge, so to speak. Jography I have always been interested in, and now, it seems to me, I have a chance to get connected with it more directly.’

‘I’ll be glad to have you with me, Mr Barley,’ she laughed, ‘if that is what you mean.’

He smiled admiringly. What a fine woman she was, he thought. ‘No, that isn’t it exactly,’ he said. ‘I was thinking more of money. You want it, we have it, as the advertisements say!’

CHAPTER II

WHAT THE MORNING BROUGHT

FOR a few moments Elaine looked at him in silence. A little twitch showed itself at the corner of her mouth, and was gone. Her lips tightened a little, her gaze became speculative.

‘What does that mean exactly?’ she asked, when her silence had made him fidget, and uneasily stir his coat-tails behind his back.

He cleared his throat nervously. ‘Nothing more than what I say, I assure you, Miss Gurdon. I hear that a good deal of money will be wanted for your new expedition. I’d like to have a hand, if not a name, in it.’

‘You are suggesting financing me?’ she said bluntly.

He nodded, relieved. ‘That’s it. I should like to. Name your figure, and I’m on. It would be a pity to spoil the ship for the sake of a hap’orth of tar.’

She considered that for a moment. She knew that the trip would be an expensive one. Barley had plenty of funds.

‘Perhaps you haven’t heard that Mr Tollard is backing me?’

He coloured a little, and she knew at once that someone had been talking. Her glance became slightly hostile. He fidgeted again, puffed gustily at his cigarette, threw it behind him into the fire-place, and smiled apologetically.

‘Well, I understood so. Yes, decidedly I knew that. At least, I was aware that he was standing some of the expense.’

‘What then?’ said Elaine, and now she held his eyes, and her own had grown hard and challenging.

‘My dear girl,’ said Mr Barley, with symptoms of discomfort in voice and manner, ‘now we come to a point that has been causing me some distress.’

‘But does not directly concern you, perhaps?’ she demanded.

‘Not directly—no. But we are all friends here. I hope we are, and, er—’

‘You think it unwise of me to accept financial help from Mr Tollard?’ she interrupted fiercely.

‘That is more or less what I meant to say,’ remarked the kind old man. ‘It may sound crude to you, the more so, Miss Gurdon, because I am not sure that you realise what people have been saying.’

‘Or don’t care?’ she fired out.

‘In this world we have to care,’ he said gently. ‘I’m old enough to be your father, my dear, and I tell you that we have to pay some attention to what others say, even if we have given them no cause to say it.’

‘That simply isn’t true!’

‘Excuse me if I say it is. If not for oneself, there are others concerned. We never live quite alone and detached in this world. I was thinking of Mrs Tollard. She may be a weak woman, and a foolish, but I feel sure her husband’s interest in this expedition gives her pain. Then she is aware of the gossip. There are always people about who are anxious to tell young wives what others say of their husbands.’

Elaine got up. ‘I don’t think I care to continue this.’

He reached out a fat hand, and put it on her arm. ‘Do hear me out. I am sure you are everything that is discreet. Tollard too. I am quite sure of it. If I weren’t, I should not insult you by saying what I have said. Look at it this way. You and Mr Tollard are old friends. You are interested in the same thing. No one of sense thinks otherwise, but his young wife has perhaps some of the natural jealousy we find in folk who haven’t been brought up to keep a hold on themselves.’

Elaine’s lip curled. ‘You describe her neatly.’

‘Very well then, is it worth while to sow discord between husband and wife, when you can avoid it by stepping the other way? Look at it that way. Let me give you a cheque for your work out there, and tell Tollard you need not trouble him. No one will know what I have just said to you.’

Elaine shrugged. ‘It won’t do at all. I know you mean well, but it won’t do. Mr Tollard would see through it at once. It would be as blunt as telling him that I thought we were in danger of falling in love with one another. I refuse to take that attitude. Margery is a little fool. I hope she has not been complaining to you?’

‘Not a word,’ he said awkwardly, ‘but I hear talk. I wish you would think it over. If on no other grounds, you might give me the pleasure of associating myself with your important exploration. It’s a weak spot in me. I’m a bachelor and without anyone to carry on my name. I should like to be known as one who did a bit in the world.’

She shook her head. ‘I am sorry. It is quite impossible. It would be an insult to Ned—to Mr Tollard. It would even seem to some a confession that there was something wrong. You must see that.’

‘Mrs Tollard looks most unhappy,’ he said.

‘It’s her own fault,’ Elaine cried hotly. ‘She has a pose. I detest her, if you must know! Like all the silly, backboneless creatures in the world, she thinks if she sits back in a chair, and smiles wanly about her, people will kneel at her knees all day and worship her. I refuse to pamper her wretched emotions. Mr Tollard and I have never been anything but good friends. I need not tell you I don’t love him, or he me. I needn’t say that a woman of my type who loved a man would not be as discreet as I have been.’

‘I shouldn’t have thought of asking,’ he said simply.

‘Then why should this miserable weakling parade a misery for which she has no justification, Mr Barley?’ she cried hotly. ‘She will end by making herself a laughing-stock, and ruining her husband’s life.’

‘Well, think it over, think it over,’ said he, disconcerted by her vehemence. ‘I am sure I meant no harm. It was just a thought of mine. I hoped it would do good. I hate to see folk unhappy.’

‘I know,’ she said, throwing away the stub of her cigarette, ‘but I am afraid I have given you the only answer I can. Do you mind if I leave you, and go into the garden? I need a breath of fresh air.’

‘Not at all. You have been very patient in listening to me,’ he returned. ‘I have a letter or two to write, so go by all means.’

Bitterness sat on Elaine’s lips as she left him, and went out through the French window into the garden. Anyone watching her now would have understood, the spirit, the resolution, the fiery energy, which had carried her through a hundred perils. Poor old Barley was like the rest of them. Whatever he said, he was afraid Ned and she were on the edge of a precipice, dallying when they ought to have stepped back to safety.

As she crossed a strip of lawn, she heard a car come up the drive. As she turned the corner of the house she saw Tollard at the wheel. His face was white and set. Margery, beside him, had her eyes down, but she was white too, and drooping.

‘The Madonna-lily pose!’ Elaine said to herself angrily.

Neither of them appeared to see her. Tollard got down, and offered a hand to his wife, his face averted. She refused it, with a delicate shrug.

Elaine went away hurriedly. Tollard gathered up his wife’s bag and books, which she had left on the seat, and followed her into the hall. She went upstairs without turning to look at him. In her fragile figure there was a lassitude that would have enchanted her Chelsea friends. Her pale face was that of a Mater Dolorosa of an Old Master.

Tollard put down books and bag on a chair, and looked about him uncertainly. Then he pushed open the door of the library, and greeted Mr Barley; who was not writing letters after all, but sitting in a chair, smoking and reflecting.

‘Got what you wanted, Tollard?’ he asked, turning to look at his guest. ‘Good. I have been having a chat with Miss Gurdon. I wanted her to let me have a share in the expedition, but she won’t hear of it.’

Tollard shrugged. ‘We have arranged that all right. By the way, Mr Barley, I shall have to go up to town this afternoon. Some urgent business I had not counted on. I am sorry to have to go in such a hurry.’

Mr Barley bit his lip. Surely Elaine had not had time to see Tollard and warn him? ‘Just as you like, my dear fellow,’ he replied. ‘I suppose Mrs Tollard will stay on?’

Tollard nodded hastily. ‘Oh yes. It’s a personal matter. I felt sure you would understand.’

Mr Barley thought he did understand. Tollard was a man of fresh colour, and now he looked pale and tired. There was something up. Perhaps he and his wife had quarrelled. Surely it couldn’t be a pre-arranged thing between him and Miss Gurdon? Elaine had told him bluntly that she did not love this man; but, if she did, she would hardly blurt it out.

‘Perhaps you are going to make some arrangements for this expedition,’ he said, hoping Tollard wouldn’t resent his curiosity.

‘No. Nothing. We have pretty well settled the thing now, and I have my own affairs to attend to. Miss Gurdon may set out at any time.’

Mr Barley nodded, reassured. ‘All right. I had hoped to take you all to see Heber Castle this afternoon, but I can count you out. You must try to come down again soon.’

‘I wonder what Barley is after,’ Tollard said to himself as he left to go upstairs to his bedroom. ‘And I wonder what he thinks. Some of those cats—’

He stopped there, and went upstairs quickly. As he passed the door of his wife’s room, he heard her moving about with her slow, light tread. He shrugged, and did not go in.

He left at half-past two for town. By three, the other guests had filled two cars, and set off for Heber Castle, a show place in the neighbourhood that was open to visitors. Mrs Tollard did not go with them. She pleaded a headache, and did not come down after lunch. Mr Barley went in one car, with Elaine Gurdon, Nelly Sayers, young Haine, and Mrs Minever. Mrs Gailey, the two Heads, and a friend who had dropped in, took the other.

‘I thought Margery looked awful at lunch,’ said Mrs Gailey, as they drove along through the sun-soaked country. ‘What a pathetic face she has.’

Mr Head grunted. ‘I don’t know really why she tries to play bridge. She has no idea of any conventions, and seems to think that the whole game consists in doubling.’

‘Perhaps that is why she looks pathetic,’ said the friend, with a smile.

Mrs Head frowned. Bridge was no subject for humour. ‘She might think of her partners,’ she remarked severely.

‘And now Ned is going off suddenly,’ said Mrs Gailey.

The friend grinned. ‘There’s the reason for the pathos. Young wife, departing husband! Why, some of them weep buckets!’

‘Tollard looked a bit fed-up too, I thought,’ observed Mr Head. ‘Last night he muddled every hand.’

‘Blow bridge!’ thought Netta Gailey. She wished she were in the other car with Nelly Sayers, who could talk of interesting things without introducing some detestable hobby. In the other car, Miss Sayers was also seeking information.

‘Mr Tollard left in rather a hurry,’ she said to Mr Barley. ‘Business, I suppose?’

‘Men always have business for an excuse; we women are not so lucky,’ grumbled Mrs Minever.

‘Business,’ agreed Mr Barley, avoiding Elaine’s eye.

‘If I had such a jolly pretty wife, I wouldn’t let any business take me away,’ said Ortho Haine enthusiastically.

‘A single man doesn’t know what a married man may do,’ said Mrs Minever.

They picnicked in a lovely dell, duly made the tour of the castle, and returned in good time for dinner. Mr Barley’s first duty on reaching home was to enquire after Mrs Tollard’s headache. She herself was not yet visible, and her maid told Mr Barley that she was not sure if her mistress would leave her room that day.

‘I hope she is not really ill,’ said he solicitously.

‘Oh no, sir. But she has a blinding headache, and will be glad if you will excuse her at dinner tonight, sir.’

‘I shall have something sent up to her. You might perhaps ask her if she would care to see a doctor. I could telephone for Browne.’

‘No, thank you, sir. She told me to tell you not to trouble, only please to excuse her.’

‘Mrs Tollard will not be down tonight,’ he told his guests, when they assembled at dinner. ‘I should think it must be a touch of neuralgia myself.’

All expressed sympathy, though Elaine’s face wore a look of slight scepticism, as if she doubted the cause of the malaise.

‘She did look seedy this morning,’ said young Haine.

‘She is a pale type,’ said Mrs Minever.

After dinner, Mrs Minever, the Heads, Mr Barley, and the Heads’ friend, with Elaine and Ortho Haine, decided for bridge. Nelly Sayers wanted Mrs Gailey to go with her to the billiard-room, where they could discuss Margery and her neuralgia to their heart’s content, but a fourth was wanted for the second table, so she sat down with a book.

At half-past eleven the last rubber had been played, and Mrs Minever closed her bag, and got up. She was followed by Mrs Gailey, Elaine, and the others, the Heads lingering almost to the last to discuss some incident in the evening’s play. Then they too disappeared, and Mr Barley was left alone with Haine, who was yawning heavily.

‘Fine woman, Miss Gurdon,’ he said to his host, raising a desultory hand.

‘Very,’ said Mr Barley. ‘Brilliant even. I have a great respect for her.’

‘Doesn’t seem to be much love lost between her and Mrs Tollard,’ drawled Haine.

Mr Barley frowned. ‘Oh, I shouldn’t say that. But you’re tired, Haine. What about bed?’

‘Bed it is, sir,’ said Ortho obediently. ‘Good-night.’

Mr Barley retired last, looking thoughtful. Half an hour later, and the house was quiet. It was a still and warm night. Isolated in its park, there were no sounds from the main road that bounded the grounds on the south side.

Mr Barley fell asleep at twelve. He had tired himself speculating about Tollard and his wife. They would come round in time, he thought. These tiffs were a part of many married lives.

He was awakened about half-past five next morning by a sound. It seemed to him low but penetrating. He sat up in bed, and listened. A soft thud followed. He got out of bed, slipped on his trousers, slippers, and a dressing-gown, and was about to go out into the lobby when there was a knock at his door.

‘Come in,’ he said, in a disturbed voice.

He thought it might be his man. To his surprise it was Elaine Gurdon.

She wore moccasin slippers, and had on a silk dressing-gown over her night-dress. Her hair had been loosely coiled on top of her head, and held there by a long obsidian pin, with an amber head. He noticed that she was very tense, though she was in perfect control of herself.

‘What’s the matter?’ he stammered.

She put a finger on her lips. ‘Don’t rouse anyone yet. Come with me, please. Mrs Tollard is very ill. She may be dead. I have just come from her room.’ Mr Barley tried twice to speak. His face was ashen. He trembled as he stood staring at Elaine. Then he followed her out of the room, and down along the passage to the bedroom occupied by Margery Tollard.

CHAPTER III

THE DRESSING-GOWN

THE bedrooms on the right side of the lobby faced south. The one occupied by Margery Tollard had a door communicating with that formerly used by her husband, which was, of course, empty since his departure.

Still silent, but much shaken, Mr Barley followed Elaine Gurdon to the door, watched her turn the handle, and push the door open. Then he advanced ahead of her into the room.

Something in the posture of the figure that lay face upwards on the floor near the window told him that Mrs Tollard was dead. He stopped to stare for a few moments, passing his hand agitatedly over his forehead. Then, accompanied by Elaine, he went forward and looked down into the dead face.

It looked haggard and tormented, the lips drawn back from the teeth in an ugly way. He shuddered.

‘I must send for the doctor at once. I don’t understand what can have happened. Will you help me get her on to the bed?’

Elaine shook her head doubtfully. ‘I don’t think it wise. I have seen many dead people before now, and this doesn’t look natural.’

‘You can’t mean murder?’ he asked, his jaw dropping.

‘I mean we had better leave her where she is,’ said Elaine. ‘Telephone at once to the doctor, and to the police. That is the only thing to do. I shall stay here until they come, or until you return.’

‘Please do,’ he said. ‘I suppose we shall have to tell the others? Shocking affair, dreadful, awful! But I must telephone. That can’t wait.’

He hurried out of the room, and slipped downstairs. He was anxious to alarm no one just yet, and at that hour most of the guests were wrapped in heavy sleep. It took him some time to get a reply from Dr Browne’s house, but, when the sleepy man at the other end of the wire heard what had happened, he assured Mr Barley that he would drive over at once.

Mr Barley next rang up the police station. Another short wait here. Then he heard the sergeant’s voice, hurriedly told him of the tragic event, and went upstairs again.

No one had been disturbed. Elaine was standing looking out of the window when he returned to the room. A great deal was required to shake her nerve. She had seen death too near, and too often, to lose control.

‘You will notice that this window is wide open, Mr Barley,’ she said in a low voice, as he went to her side, ‘top and bottom.’

‘So was mine,’ he said, rubbing his hands nervously together. ‘It was a very hot night.’

‘At all events, remember it,’ she said, so significantly that it rang in his head for long after. ‘Is the doctor coming?’

‘Yes, and the police sergeant. Dear me! Dear me! What ought I to do? The people here will be alarmed. Will it be wise to defer telling them?’

‘For the present, yes,’ she said.

‘And later on I could make arrangements for them to go.’

She shook her head. ‘The police may want to see them all.’

The thought of the police worried him. ‘I think I must lock up this room then. We can’t stand here. I don’t like it. If we could have put her on the bed, it would have been different, but she looks terrible lying there.’

‘Very well,’ said Elaine. ‘It’s lucky most of the others are sleeping in the other wing of the house. Only Mr Haine is in this—beside my room, and her husband’s.’

‘Poor Tollard!’ he said, ‘I had forgotten him. What a blow it will be! How he will reproach himself for being away. But, Miss Gurdon, surely it’s possible she died naturally? She was not well yesterday, had a violent headache, and did not come down later—’

She touched him on the shoulder. ‘We shall see all that later. We had better lock up this room. I must get dressed, and you too. The doctor might be here in a few minutes.’

He turned to the door. ‘You are so practical. Yes, I must dress at once. I am sure Browne will be shocked when he sees her. But we mustn’t talk here.’

He let her out, followed himself, withdrawing the key, and locking the door from the outside. He was far more disturbed than Elaine, unusually shaken for such a stolid and experienced man.

‘Don’t tell the others till after breakfast, if you can avoid it,’ she whispered, as they parted outside her room.

He shook his head mournfully, and went off to complete his dressing. He did not shave. As he put on his collar he suddenly remembered that Miss Gurdon had not told him why she had gone into the dead woman’s room. He supposed that, like himself, she had heard that extraordinary sound, and the thud. In the light of what he now knew, it occurred to him that the latter noise must have been the sound of Mrs Tollard’s fall. In that case her death must have taken place at the most a few minutes before Miss Gurdon came to tell him that something was wrong.