Полная версия

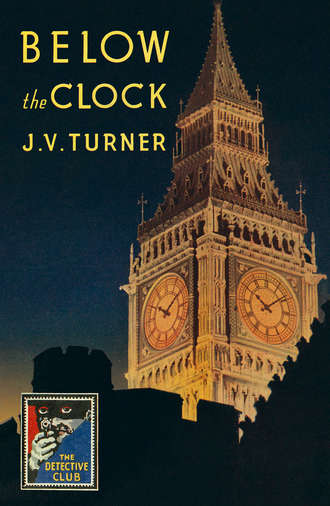

Below the Clock

Curiously enough, there were those in the House who sat with lips moving in disguised smiles. They could see some element of comedy. A death was shrieking to be investigated, and the only witnesses were objecting to being questioned in a particular place, were arguing about the conditions under which they might give statements.

Joe Manning felt that as Leader of the Opposition it was essential that he should enter the fray. He rose with a cough.

‘Everyone knows,’ he commenced in sarcastic parody of the Prime Minister, ‘that the effects of poison may be long delayed. So why should members be troubled about a matter of which they know nothing when the death may have been the result of something that happened hours before the collapse?’

His supporters cheered feebly but ceased abruptly when Ingram commenced to reply. The Prime Minister spoke slowly, chose his words with scrupulous care:

‘I am told that the fatal dose must have been absorbed at some time between a few minutes and a few seconds before death.’

The implication was obvious—and ugly. Eric Watson regarded it almost as an accusing finger. He found himself rising to his feet and stopped when he heard another voice raised. Curtis was up, his hands resting before him, his strong voice strangely strained.

‘We naturally accept the statement in good faith as the best that can be afforded at the moment. I think it right to indicate to the Hon. Members, however, that the Prime Minister’s final remark definitely implies that every Member is a potential suspect.’

He paused and a rippling whisper wafted round the House.

A Member in a far back bench commenced to giggle. The Speaker intervened with no uncertain tongue:

‘If the Honourable Member cannot control his mirth it might be better if he indulged it outside the House. This is a serious matter.’

Ingram looked at Curtis as though grieved. The barrister had said what the Premier had carefully avoided. Curtis sat down.

‘In the long history of this House,’ said the Premier, ‘there has been no such thing as a suicide. It is true that a murder did occur, but that tragical happening took place outside in the Lobby. I mention those two facts for one reason only—so that you will rightly regard the present set of circumstances as entirely without precedent. That being so I feel justified and compelled to ask this House to take exceptional measures to deal with it.’

No arguments were raised. Members were oppressed by the oddities surrounding the death, by the peculiarities of this new type of heart failure. Ingram had certainly suggested that a murder had been committed while they were all looking on!

Watson shivered as though seized with an attack of ague. But the day was warm, and the House overheated. Curtis smiled consolingly. Watson nodded, anxious to get outside the building.

The Prime Minister scribbled a note and had it passed to Watson. Eric read it twice before he grasped the meaning of the contents:

‘The small man in the pew under the gallery is in charge of the investigation. Rough hair, untidy clothes, rimless glasses.’

Watson flushed almost guiltily. Why should Ingram pass on the information to him? Then he pulled himself together, realised that he was solely in charge of Reardon’s papers which the police would want to examine. Watson rose and walked to the pew which is reserved for Civil Servants whom Ministers on the Treasury Bench may want to consult at short notice. Watson felt less alarmed when he saw the little man. There was a disarming air of simplicity about him.

‘Are you anxious to get rid of me?’ he asked Watson.

‘I didn’t know that you knew me. I only came to say that I’d like to hand over Reardon’s papers if you are ready to look them over. The keys have been given to me and I want to go home.’

‘I’ll be sorry to leave this seat. I found it all most amusing.’

‘You’re the only person here who could see the joke.’

Watson stopped abruptly and looked at the solicitor. Perhaps, after all, he wasn’t as innocent as his appearance advertised. They did not speak as Watson led the way through the door at the back of the pew and entered a lobby, walking from there to the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s private room. Amos glanced round the chamber with sudden speed, and sat down on the edge of a table. He seemed quite happy and entirely at ease.

A half empty bottle of claret stood on a side shelf. Petrie eyed it almost casually and passed no comment.

CHAPTER V

WATSON PLAYS FOR SAFETY

‘SEEMS impossible that a murder could have taken place in there before hundreds of people until you’ve seen the place,’ said Amos.

‘It seems less improbable to you now?’

‘Much. I sat in that pew working out a few ways in which it could be done. But most of my schemes lacked finesse.’ Petrie wagged his head to indicate that deficiency in finesse was as deplorable as the murder itself. Watson again felt confident. There was nothing to fear about this strange little person. Watson thought it over and decided to take a gambler’s throw and clear the atmosphere.

‘Among these theories you’ve been working out, did you find one that fitted me?’

Petrie produced his handkerchief and his voice dropped a tone:

‘I’ve got a separate theory for you—one all for yourself.’

Eric repressed the shiver that coursed down his spine and took another plunge:

‘Thinking, of course, of the claret and soda?’

Amos nodded brightly, almost as though seized by sudden delight.

‘I don’t want to ask you about that now. But I don’t mind telling you that one man felt inclined to arrest you last night.’

‘Meaning Inspector Ripple?’

‘Yes. You know him?’

‘His fame reached me last night,’ said Watson nastily. ‘He was pictured to me as a person lacking in your favourite finesse.’

‘Dear me! Poor Ripple would be mortified to hear that. I’ve blamed him at times for many things—but never for that. It’s too bad.’

‘The man deserves all that’s coming to him if he thinks I’d poison a friend with six hundred people looking on.’

‘It would be gauche,’ conceded Amos. ‘Very gauche.’

‘Why don’t you want to question me about the claret and soda?’

‘My friend, when I go fishing I study the conditions of the stream before I throw in my line. I don’t know enough about this case yet.’

Petrie was staring over Watson’s shoulder. The younger man grew restive, turned to discover that the solicitor was looking at a blank wall and bit his lips as he considered the position. Finally, he commenced to speak with a burst of words:

‘Look here, I’m in rather a mess. I’m not standing in too good a spot. It might be said that things look suspicious as far as I’m concerned. But I’m prepared to put myself in your hands. You can make any search you like and I’ll answer any questions you like. I can’t be fairer or more open than that, can I?’

‘Perhaps you can’t. It might be an advantage.’

‘An advantage to me?’

‘Possibly. Who can say? Ever do any fishing yourself?’

‘Fishing? What on earth has that got to do with it?’

‘Nothing at all,’ replied the little man easily. ‘You’ve missed a lot, my friend.’ He looked round the room as though taking his first glance. Then he pointed to the claret bottle.

‘Is that the bottle from which Reardon’s last drink was taken?’

‘That’s the one, and I poured out the drink personally.’

‘How interesting. For myself I prefer beer. But it takes all sorts to make a world, and I can’t blame anyone for liking claret. I don’t think many people would like to drink out of this bottle.’

‘Surely you don’t think the strophantin was in the claret?’

‘I never could guess. Pity I’ve lost my palate for wine.’ Petrie removed the cork and sniffed the contents of the bottle daintily. He had a wholesome respect for strophantin fumes—if any were present. Watson eyed him suspiciously, waiting for some change of expression on the wrinkled face. The solicitor smiled.

‘Can you lend me some sort of a case so that I can take this bottle away? The stuff will have to be analysed.’

Watson produced a small attaché case and the bottle was stowed away.

‘Do you live very far from here, Mr Watson? By the way, I didn’t mention before that my name is Amos Petrie. Not that the name matters but I suppose there is some sort of etiquette even about murder cases. Now that we know each other—where do you live?’

‘I have a flat in St Margaret’s Mansions. I live at the top.’

‘Like an eagle in his eyrie, eh? Aren’t the Mansions in Millbank?’

‘That’s right. Only round the corner, so to speak.’

‘I’d like to amble round and peep about the place for a while.’

‘I told you that I am willing for any search to be made.’

‘Splendid. We’ll start now. I can collect your friend Ripple on the way. Maybe you’ll like him more now that the raw edges of a first meeting have worn away. Hand me Reardon’s papers and we’ll walk.’

Watson felt inclined to protest against the sudden move. Petrie stood near the door, waiting for him. Eric shrugged his shoulders, collected the papers, tucked them into two despatch cases, and handed them over. They met Inspector Ripple in the courtyard. He was talking to a sergeant. Amos handed the case containing the claret bottle to the sergeant, instructing him that the contents were to be sent for immediate analysis. The documents were handed over to be left in Ripple’s room. Then the three men walked to Millbank.

They rose in the lift to the fifth floor and were admitted to the flat by a manservant. Ripple took a quick look round, and phoned to the Yard for another man to assist in the search. Amos sat down in a small lounge and waited for the scrutiny of the flat to begin. He was as placid as a removal contractor. Watson found it difficult to settle down and over a whisky and soda he recounted to Amos all that happened on the previous day from the time he entered the House until he left it. He was still adding details to the story when Ripple and his assistant commenced the search. Half an hour later Ripple returned to the lounge, holding in his hand a small bundle of papers.

‘These papers and oddments seem to be the only things of any value,’ he announced.

‘And no trace whatever of any strophantin?’ asked Watson.

‘None whatever,’ replied the Yard man, looking at the speaker curiously. ‘Why? Did you think we might find some?’

‘I was sure that you wouldn’t. I’ve never heard of the stuff until this morning. Perhaps you’re satisfied now?’

‘Don’t speak before you think,’ said Petrie curtly. ‘If you gave the strophantin to Reardon it isn’t very likely that you’d have kept some of the stuff in your flat. And since you were so certain that there was no poison here why did you ask whether any had been found?’ Before Watson could speak Petrie picked up the bundle of papers and commenced to run through them. Eric watched him closely. The search was conducted at lightning speed, paper after paper being dropped on the table as soon as they had been glanced at. Then Amos stopped abruptly. In his hand he held a photograph.

Watson could not see it. He did not need to. He knew it was a woman’s. Petrie raised his eyes and Eric reddened under the inspection.

‘When you were talking to me you said nothing about the lady. Did you think the matter so unimportant?’

‘There’s nothing to tell. Otherwise I would have spoken.’

‘I see. Well, we’ll take a look and see whether the photograph itself can give us any information. I’m sure you don’t mind.’

Amos did not wait to discover whether Watson objected or not. He opened the back of the frame and extracted the photo. Watson looked on with dull resentment. His anger rose when the little man turned the photograph over and inspected the face for a full minute. Finally he tapped the frame on the table and examined what fell out, making sure that it was neither makers’ shavings nor packer’s dust.

‘There’s no mystery about it,’ snapped Watson. ‘It’s an old photo.’

‘I see it is,’ said Amos calmly. ‘Judging from the last time I saw Mrs Reardon it must have been taken about ten or twelve years ago. You had it in a different frame not long ago. I think the lady was foolishly impetuous when she scribbled on this. Was she a classical student? “Omnia vincit amor. Lola.” Very pretty. I suppose that means, “Love conquers all things”? I wonder whether it conquers death—particularly sudden death? Do you think Mrs Reardon imagines that love is quite so potent? Maybe she has changed her mind by now.’

Watson squirmed, wanted to throttle the man. He started to speak and stopped when he saw Petrie take another photograph in his hand.

‘Well, well, well, Mr Watson! Now this one does tell a story. I see it’s quite new. It’s never been framed and there’s no dust on it. H’m, rather looks as though the ancient affection has continued to quite recent times. This was taken about a year ago, I imagine. I wonder whether Mrs Reardon ever contemplated inscribing this one as she did the other? I see she hasn’t even signed it. I believe I might have suggested something suitable for her to use—although I was never a classical scholar.’

‘Oh, yes? And what would you have suggested?’ Watson sat forward tensely, wondering whether Petrie would give away a clue to his thoughts. The solicitor scratched his forehead before replying:

‘My French is very elementary. Still, I seem to remember someone writing: Mais on revient toujours a ses premières amour. Perhaps you’ll agree that it would have appeared pleasing on the bottom of this second photograph?’

‘I can see no possible reason why Mrs Reardon should write about one always returning to one’s first love. If you think it at all remarkable that I should have been presented with a photograph quite recently may I remind you that I was Parliamentary Private Secretary to the lady’s husband? Apart from that your acuteness dazzles me. I don’t know how you work these things out.’ Watson was too heavily sarcastic and it displeased him to see that Petrie was smiling as though appreciating the rebuff.

‘I had recalled, of course,’ said Petrie, ‘that you were Reardon’s P.P.S. But I am incredibly dense. It had not occurred to me that that was why you kept his wife’s photograph in your bedroom. I didn’t appreciate that it was part of your duties. I will never be able to understand the complexities of politics.’ He shook his head almost mournfully and Watson cursed silently. This little man was not quite as harmless as one assumed.

‘From the colour of my necktie,’ he sneered again, ‘I suppose you deduce that I am in love with the lady?’

‘Not exactly,’ replied Amos casually, ‘I imagined that from your former silence and your present anger.’

The calmness of the judgment made it more devastating. It seemed to Watson that those few words encompassed all he dreaded. They stripped him of his anger and his sarcasm. He was unmanned. Now he stared at the curious person whose suspicions he had aroused and whose suspicions had travelled so far.

‘Had you forgotten those photographs, Mr Watson, when you asked me to search your flat?’

‘Not at all. It never occurred to me that they, or she, had anything to do with the matter. Nor does it now. Even assuming that all your deductions are right I don’t see how the photos affect the issue.’

‘No? Then you don’t recognise that even ladies are at times associated with such crimes as murder?’

‘Perhaps, in some cases, they are. But this time you are hopelessly and hideously wrong.’

‘I’ve found myself entirely wrong before today—particularly when fishing. Ripple, you haven’t much to say. Are there any questions you’d like to ask Mr Watson before we leave?’

‘One or two. You must expect some bluntness from me,’ said the Yard man. ‘I don’t play about with words.’

‘My friend does not practise the art of finesse,’ remarked Amos.

‘I have already been informed about that,’ said Eric surlily.

‘Did Reardon know that there had been an affectionate association between yourself and his wife before her marriage?’ asked Ripple.

‘I couldn’t tell you. He was not the sort of man to worry about that. In any case, he had every right to trust me and he did trust me.’

‘Do you consider that Mrs Reardon is in no way concerned with her husband’s death?’

‘Good God, man! I am certain upon that point. Don’t be ridiculous.’

‘Then why have you swerved away from questions, become annoyed over trifles, and acted like a person with a lot to hide?’

‘I have acted quite straightforwardly all the way through.’

‘Was that bottle of claret unopened when you took the drink out of it for Reardon?’

‘Quite untouched. I had to extract the cork myself.’

‘You would have noticed if the bottle had been tampered with?’

‘Naturally. I can swear that it had not been touched.’

Petrie frowned and rapped on the table.

‘Are you trying to make things as awkward as possible for yourself.’

‘Certainly not. I am telling you the truth. Don’t you believe me?’

‘Did Reardon instruct you personally to bring him a claret and soda? I know that he would take a drink, but did he specify what sort of drink he wanted?’

‘Certainly. Men don’t drink an unusual mixture like that by pure accident. Surely you know that without asking me?’

‘Being nothing except a beer drinker I couldn’t answer you. I don’t think we’ll detain you any longer. When you see Mrs Reardon again you might tell her that within the next few hours I’ll call upon her. It might save her from a shock when I arrive.’

‘Is it necessary, Mr Petrie?’ asked Watson anxiously.

‘Entirely so—and you haven’t helped her position.’

‘I haven’t?’ Watson seemed staggered, quite amazed. ‘But I’d never do a thing to make difficulties for her.’

‘Perhaps that accounts for most of the trouble. Your object in asking me to come here has failed. Partial revelation is never of any service to a man unless he’s fighting for time. Instead of clearing yourself and getting Mrs Reardon out of the line of inquiry, you’ve merely presented me with a new problem. You have compelled me to ask myself whether you can have any object in gaining time.’

‘Mr Petrie, this is outrageous!’

‘Believe me, my friend, nothing is further from my immature mind than outrage. I came here thinking that you might assist me and that in return for your help I might give you a few words of fatherly advice. You have not enabled me to do anything of the kind. The only way in which you can help me is by complete frankness. I hope you’ll bear that in mind. It might assist you the next time we meet—and that will be before much more water flows under Westminster Bridge.’

‘Doesn’t sound as though you’re satisfied,’ said Watson.

‘I’m not. Oh! Before I go would you mind telling me what you know about this man Paling?’

‘That’s quite easy. I only know that he has been associated with Reardon during the last twelve months. I don’t know how, why, or where they met, and I don’t know what they had in common. It always seemed to me that they were frightened of each other. That’s all I know.’

‘Doesn’t help me. Thanks very much.’

Petrie and Ripple left the building and walked round to the Yard. The miserable Ripple was more melancholic than ever.

‘This case will never break in a month of Sundays,’ he complained.

‘Maybe it won’t, Sunshine. You’ll find when you do get to the tail end of it that all your trouble has been worthwhile. I can see quite a lot of things that don’t fit. It may help us to discover what’s happened about the analysis of that claret. At any rate, the report should give us a start. Think it will be ready?’

‘I imagine so. I’ll give a ring as soon as we reach the office.’

Petrie sat down with a copy of the Fishing Gazette while the Inspector got his number. The little man heard Ripple’s request for information and then saw the man’s jaw sag. The Yard man slapped down the receiver and slumped into a chair.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.