Полная версия

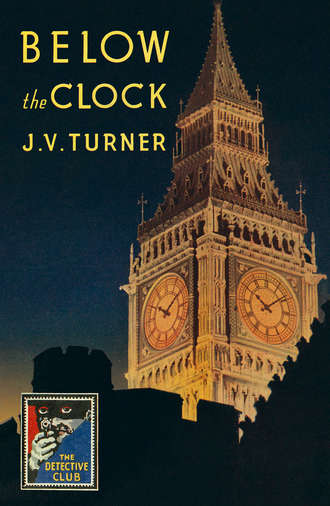

Below the Clock

The murmurs grew until individual voices were clear. The impatient were begging him to proceed, Opposition members sneeringly suggested that he had every cause to hesitate, and the members of the Cabinet urged him to hurry, admonished him against delay.

At last Edgar Reardon turned away from his notes and resumed his position in the spotlight, leaning his elbow on the Despatch Box. His gaze wandered round the House before settling upon the face of Joe Manning. The leader of the Opposition moved a little uneasily. The Chancellor stared at him as though the first announcement was to be a direct, personal challenge.

But Reardon hesitated unaccountably on the brink of that announcement. Joe Manning’s face flushed and he started to rise to his feet. Even as he moved he spoke, his voice burdened with temper:

‘Why this farce, Mr Chancellor? Are you so ashamed of the Budget you have to produce that your nerves have failed you?’

The questions provoked cheers from the Opposition members. Ingram, the Prime Minister, rose with a retort, hoping that the Chancellor would save the situation by speaking first.

Reardon frowned. Then his mouth twitched. His left hand groped until it found a corner of the Despatch Box.

For the first time Members began to suspect that something had gone wrong, that all was not well. Within a few seconds suspicion grew to a certainty. Reardon’s eyes were strange. They ceased to wander, were fixed in a persistent stare. The pupils shone strangely, and the man’s body stiffened until it seemed unnaturally tense.

His appearance changed with each fleeting second. He seemed numbed, almost paralysed. Even the golden light from the sun could not disguise the pallidity of his face. Reardon looked distressingly like a man who stands in a daze after concussion.

A colleague decided that it was time to act. He rose and caught the Chancellor by the tails of his coat from behind.

It seemed that the action was the only thing wanting to upset the Chancellor’s balance. He fell headlong to the floor with a crash!

The moment that followed was one of those in which the whole being is concentrated in the eye. The hush that fell over the House was poignantly dramatic. It was an uncomfortable silence.

Tranter broke the spell by claiming right of passage, and dashing forward to the side of the Chancellor. Members who had sat with the muteness and stiffness of statues found their tongues. Ingram cast the secrets of the Budget all over the table in a frenzied search for water. Abruptly he seized the remains of the claret and seltzer, flung it into the face of the Chancellor. Reardon did not move.

Watson, the P.P.S., recovered sufficiently to run for water. As he hurried the Hon. John Ferguson, President of the Board of Trade, worked with trembling fingers and whipped off the man’s collar. Sam Morgan, anxious to help, but uncertain of the procedure, stood wishing that he were a doctor instead of a Home Secretary.

In the general confusion everyone succeeded in getting in everyone else’s way.

At last Tranter produced some sort of order out of the chaos. As he knelt down by Reardon’s side he gave short, sharp directions to those around him. He was definitely a better doctor than he was an economist. The whispering ceased. There was a silence ladened pause. Then Tranter raised his voice again:

‘Carry him outside at once.’

The prostrate form was seized by half a dozen willing, but clumsy, hands. Reardon’s flaccid muscles writhed under the pull and thrust of the shuffling figures, the trunk bowing as they lifted him. The helpers bustled him into a position they fondly hoped was comfortable. It was a grotesque parody of a chairing. The Chancellor’s head wobbled hideously, the body sank into itself telescopically, looking invertebrate and horribly unhuman, swaying and jolting to each step of the bearers as they staggered with their burden out of the House.

The Members watched the procession with bewilderment. This was something that the Chancellor had not budgeted for! They need have felt no sympathy for the sagging figure.

Edgar Reardon was dead!

CHAPTER II

BEHIND THE SPEAKER’S CHAIR

‘I SUPPOSE it was apoplexy,’ whispered the Prime Minister.

‘I can’t tell definitely what it was,’ said Tranter. His brows were knitted, and there was a tone in his voice that the other misjudged. The group stood in the long hall behind the Speaker’s Chair. The body of Edgar Reardon lay on a couch against the wall. The figure was dishevelled, the head was supported on the rolled-up jacket of the dead man, one of the legs had slipped off the side of the couch.

‘If there’s any room for doubt,’ said Ingram after a pause, ‘we’d better have him taken across to Westminster Hospital’

The doctor waved his hands impatiently and commented sourly:

‘Oh, I know death when I see it. He was dead when we carried him out of the House. I’m not troubled about that. What’s worrying me is that I can’t figure out how it happened.’

‘But, man, you saw it all yourself,’ protested the Prime Minister.

Tranter’s nerves were ruffled and his temper ebbed. He flung his hands helplessly into the air.

‘Of course, I saw all that you saw,’ he snapped. ‘But I’m a doctor. This, Ingram, is a case for the Coroner of the Household. I don’t want to say much more. An autopsy may show that death was due to natural causes. His heart may have given out; a hundred and one things may have happened. But I’m going to say this now: It didn’t look to me like natural death at the time when it happened and I don’t think it was even now. Just look at him. Does it look right to you?’

The Prime Minister gazed at the corpse and shuddered. Reardon certainly did not look as though his heart had failed him. There was something odd about the expression of the face, an atmosphere of violence about the distorted limbs. For years Ingram had boasted that he was able to cope with any emergency. That faculty, and his solid sense, had won him the Premiership. But now he felt as though his brain were addled as he groped feebly after an idea.

The Cabinet Ministers who had assisted in carrying the Chancellor out of the House stood in a group like frozen images, staring with awed fascination at the corpse, and not trusting themselves to speak.

A little farther away the widow stood against the wall, her body twitching, her startled eyes, distended but dry, turning from Tranter to Ingram, and from Ingram to the remains of her husband. Her face was tragically pathetic. The skin was marble white and her make-up turned her pallor into a shrieking incongruity. The mascara on her eyelids and lashes showed midnight black against a surround of ghastly white; rouge, high on the cheek-bones, was almost silhouetted against the pale flesh, and the lips swerved in a carmine spread. Her green eyes were overshadowed by grief and mascara. Tufts of golden hair caught the rays of the sun as they waved in curls from the side of a black cloche hat.

Watson flitted in the background like a hovering moth, straying from Tranter’s side to whisper condolences to the widow, moving again to stare at the corpse as though he still disbelieved that Reardon was dead. As seconds passed Ingram’s brain began to function again.

‘Tranter,’ he said, ‘this is absolutely absurd. I can’t understand what on earth you’re talking about. Edgar Reardon was a man without a care in the world. Why should a man with position, money, good health, and a devoted wife commit suicide? And you suggest that he didn’t die a natural death! The idea is preposterous.’

‘You’ve been thinking instead of listening,’ remarked the doctor caustically. ‘I did not say that he committed suicide at the time of his death, and I don’t say so now. I haven’t mentioned suicide.’

‘But … but …’ Ingram paused, bewildered. He did not complete the sentence. Before he could collect his scattered thoughts a shrill laugh interrupted him, a peal that broke abruptly at the end of a high trill. If the roof of the House had fallen through it would not have created a greater sensation than the unexpected sound. On the overwrought nerves of the men in the hall the effect was hair-raising. They wheeled round together.

Mrs Reardon stood with her head tilted back, the face entirely mirthless, the mouth twisting with spasmodic jerks, the eyes wild and distended. Here, at least, was a case which Tranter could treat with confidence. Before he reached her side Mrs Reardon had ceased to laugh and her body was convulsed by sobs. Watson handed the doctor a glass of water. Tranter threw it into the face of the hysterical woman. As she quietened down he tried to speak to her persuasively. The effort was useless. She was quarrelsome and querulous. Watson stood by her side, gripping her trembling hands.

While Tranter was attempting to coerce the woman a newcomer arrived, walked across the hall towards them. He was tall, and a trifle too elegant, his clothes immaculately tailored, his features sharply defined. The grave, dark eyes were luminously brown. He stopped before the widow and bowed. Mrs Reardon moved Tranter to one side and stared at the newcomer ungraciously, almost venemously.

‘How on earth do you come to be here, Mr Paling?’ she snapped.

The man accepted her insulting tone without change of expression.

‘Your husband,’ he said, ‘was kind enough to procure my admission to the public gallery, and I saw what happened. I have taken the liberty of ordering your car. It is now waiting. That is what I came to tell you.’

‘Oh, did you?’ Her voice was tart, her manner definitely rude.

‘It was my desire to be of assistance,’ said the man easily.

‘Thanks.’ Mrs Reardon sniffed, dabbed at her eyes with a frail lace handkerchief. In an instant her grief changed to anger again. ‘I prefer to walk home. Give that message to my chauffeur.’

The men in the hall watched the fast-moving scene with amazement. It seemed odd that a man of such appearance, of such apparent self-confidence, should make no retort. He smiled gently, a chiding smile such as a mother might bestow upon a much loved but unruly child. Then he bowed slightly and retired from the hall.

Tranter led her to a chair, comforted her for a short time and then walked away, leaving Watson by her side. Farther away in the hall an informal meeting of the Cabinet was already in progress. The Prime Minister was urging an immediate adjournment of the House.

‘I’m not going to make a Budget speech myself,’ he said, ‘and I’m not going to listen to one from anyone else. You couldn’t expect the House to sit through a speech after what has happened.’

John Ferguson, the President of the Board of Trade, added more weighty reasons to support Ingram’s argument:

‘Adjourn the House. None of the taxes has been announced so you haven’t got to do anything with the Budget resolutions tonight. There isn’t any danger of premature disclosure. We’re just where we were this morning.’

Ingram nodded. The question was settled. While the Ministers talked Curtis joined Mrs Reardon and Watson in the hall. Between them they persuaded the widow to leave the House, and both gripped her arms as she walked falteringly to the door. Curtis hailed his own chauffeur and they escorted Mrs Reardon to 11 Downing Street.

The Prime Minister said little to the occupants of the House. In two sentences he informed them that Mr Chancellor Reardon had met an unexpectedly sudden death and that the House, as a tribute to the memory of the deceased, would adjourn immediately.

Shortly afterwards the last loiterer departed. The House was empty, except for what had been the Right Honourable Edgar Reardon and the attendants in evening dress, their shirt fronts decorated by the large gilt House of Commons badge. They watched over his bier …

For two or three hours Watson and Curtis made inquiries here and there, striving ineffectively to straighten out the mystery for the sake of the distressed widow. They found more difficulties in their way than either had anticipated. A sudden death in the House of Commons, apart from the fact that death has occurred, is unlike that which takes place anywhere else. Rules and laws which have been embedded in the dust for centuries hamper inquiries, tradition erects formidable barriers. The two men were unable to report any progress when they arrived at 11 Downing Street.

They found Mrs Reardon alone in the drawing-room. A black velvet evening gown accentuated her pallor. She swayed to and fro as she spoke to them. Watson avoided her eyes as she looked at him. At other times he looked at nothing else. But once she became conscious of his glance, and searched for it in return, his eyes coasted round the room. It was an uncomfortable and depressing hide-and-seek. Curtis coughed informatively and stroked his hair. Watson blushed. The widow still seemed dazed. An awkward silence arose. The woman broke it:

‘But you must have discovered something. What happened? Edgar had never been ill as far as I know. How did he—what killed him?’

‘Had he been to see a doctor recently?’ asked Curtis.

‘No, not since I’ve known him. Edgar was always terribly fit.’

‘Would you mind if I telephoned to his doctor, Mrs Reardon?’

‘Of course I wouldn’t. I’m only too grateful to you for helping me. It’s Dr Cyril Clyde, of Welbeck Street.’

The widow and Watson sat miserably silent while Curtis was out of the room. Fleeting glances passed between them. The woman’s fingers were jerking nervously. Again and again a shudder caused her body to move with the agitation of a marionette. They were both relieved when Curtis returned.

‘Only makes things worse,’ he announced. ‘I told him what had happened, and he says that your husband, Mrs Reardon, was a singularly healthy man, that his heart was perfectly sound, that he was not known to suffer from any ailments, and that he was the last man in the world who would die with such suddenness from natural causes.’

‘What does he suggest doing, Mr Curtis?’

‘He talked about going to the House to take a look at the body. I told him that he could, of course, make an attempt, but I doubted whether he would gain admission. The matter is now in the hands of the Coroner of the Household, and he is not in the position of an ordinary coroner. But he can try.’

The woman was again silent for a time. Suddenly she sat stiffly erect and stared at Curtis.

‘Do you mean,’ she asked, ‘that there is going to be an inquest?’

She was bordering on another lapse into hysteria. The two men glanced at each other. Watson left Curtis to soothe her.

‘Just a pure formality,’ he said casually. ‘Nothing at all for you to trouble about.’ From that point Curtis disregarded the curiously embarrassing glances of both Mrs Reardon and Watson as he maintained a thin stream of talk, striving to dim the tragedy in the widow’s mind. His idle chatter covered a vast range, skimming here, dipping there, but the light, discursive style had its effect. Ten minutes afterwards neither could have remembered a thing he said. Yet he had fed the woman’s mind with a flow of comforting suggestions, sliding away dexterously from any subject which might call for a reply. In that way he broke the silence gently rather than by expressing any views or feelings.

Curtis had just drawn to a conclusion when a knock sounded on the door. A manservant entered.

‘Mr Paling would like to see you, madam,’ he announced.

The widow closed her top teeth over her lip and tapped her foot irritably. Watson half rose, opened his mouth as though to speak and suddenly sat down again. Curtis looked from one to the other with a puzzled frown on his forehead.

‘I do not wish to see the gentleman tonight,’ said Mrs Reardon.

The manservant bowed and retired. But he soon returned. This time the widow glared at him angrily.

‘Mr Paling says his call is reasonably important, madam, and he thinks it advisable that you should speak to him.’

‘Show him in,’ she snapped. She moved from her seat and stood at Watson’s side. The two men rose. Paling strolled into the room with an easy style and a confident manner. He scarcely looked the part of a man who had been curtly rebuffed.

‘What is it?’ asked the widow. She might have been speaking to a recalcitrant dog. Paling continued to smile. Small veins were pulsing in Watson’s forehead.

‘I thought I would call to tell you, Mrs Reardon,’ said Paling, ‘that a detective—I think his name was Inspector Ripple—has just called on me to ask what I know about the … eh … the tragedy.’

The widow threw a look at Watson that was at once both startled and apprehensive. The creases on Curtis’ brow deepened.

‘A detective?’ repeated the woman. ‘What on earth does that mean?’

‘They haven’t lost much time in getting to work,’ said Curtis.

‘Getting to work?’ queried Watson. ‘What on earth have detectives got to do with Reardon’s death?’

‘I suppose they’re making inquiries instead of the coroner’s officer,’ said Curtis soothingly. ‘You’ve got to remember that this is not a routine matter. When things happen in the House of Commons the aftermath runs along lines outside the ordinary track.’

‘One would have imagined that this man Ripple would have seen me before anyone,’ said Watson.

‘You’ve got your turn to come,’ remarked Curtis.

‘I thought it only right that I should call and give you that information, Mrs Reardon,’ said Paling, ‘and since I realise the extent of my unpopularity I’ll leave. Good-evening.’

The widow did not glance at him as he walked out of the room. She appeared stunned. Watson was in no condition to quieten her nerves. He drummed on the top of a chair with his fingers and licked his dry lips. It seemed that a fresh emotional disturbance had arisen.

‘I think,’ said Mrs Reardon deliberately, ‘that I hate that man Paling more than any person I have ever met. I loathe him.’

‘Come now!’ pleaded Curtis, ‘I don’t know him at all but his news wasn’t in any way bad, and it was pretty decent of Paling to drift along and tell you. Perhaps he was only trying to be considerate.’

The woman pursed her lips. The men watched her. When she spoke the words poured in a flood, sounded so ladened with venom that hysteria might have explained them:

‘That’s the trouble. He’s always considerate about things that don’t matter. For nearly a year I’ve tried to stop him coming to this house, almost gone on my knees to Edgar to bar the man from here. I couldn’t do it, couldn’t do it. And I’m supposed to be the mistress of the place! I hate, loathe, and detest the man.’

‘He seems a gentleman,’ protested Curtis.

‘Gentleman? Pshaw! I hate him.’

‘Now I should have thought—’ The sentence was not completed. A knock sounded and the manservant entered again.

‘Chief Inspector Ripple wishes to speak to Mr Watson.’

Mrs Reardon slumped into a chair. Curtis wiped his hand across his forehead. Watson stalked out of the room as though marching to meet a firing squad. The door closed. The widow commenced to sob.

‘I think you ought to take a sedative and retire, Mrs Reardon,’ said Curtis. ‘You are too overwrought, and each minute is making you worse. If you don’t get to bed you’ll be mentally and physically exhausted.’

‘I couldn’t sleep, positively couldn’t. I just want to be quiet, to be still while I realise that I’ll never see Edgar again.’

She pushed a box of cigarettes towards the man. The hint was obvious. He lit a smoke and sat on the arm of a chair, swinging his legs, and trying unsuccessfully to blow rings. Seven or eight minutes dragged by before the door opened again. Watson entered, a little less jaunty, a trifle more pale. She stared at him with wide eyes.

‘Has he given you a real third degree interview?’ asked Curtis.

‘Asked me about two million questions. All of them uselessly mad.’

‘Did he happen to worry you at all about the claret and seltzer?’

Watson started. The widow looked at Curtis with the sudden head twist of a frightened bird.

‘He seemed to be more interested in that infernal drink than he was in anything. I told him what bit I knew about it.’

‘Did he seem satisfied when you’d finished your statement?’

‘Those men are never satisfied, Curtis. Why, he even started talking about murder. Either that man is mad or I am.’

Whichever was mad, Mrs Reardon was not conscious. She had fainted.

CHAPTER III

THE START OF THE HUNT

MINUTES passed before Mrs Reardon returned to consciousness. She shuddered, stared round the room with haunted eyes. Watson patted her hands consolingly. Curtis waited for the widow to speak, wondering what her first thoughts would be as full consciousness returned.

‘Why didn’t Paling die instead of my husband?’ she inquired.

The men tried to hide their surprise. Watson slipped another cushion under her head and said nothing.

‘Oh! The number of times I told Edgar, grovelled to him, begged him, not to have any more to do with the man. But it made no difference. He was always on the doorstep.’

‘Perhaps Edgar was fond of him,’ said Curtis.

‘Fond of him? I’m sure he wasn’t. He got no pleasure out of the man’s company. It wasn’t that Paling couldn’t talk. He certainly could, and he’d been everywhere. But they never had anything to talk about. While they were together it always seemed to me that some sort of a struggle—a silent struggle—was going on. I couldn’t understand it. I hated it.’ She paused to recover her breath.

Then she rose from the chair. Every sign of her listlessness had gone. The effects of the faint had vanished. Her eyes shone with anger, her breast moved convulsively.

‘What was he to your husband?’ asked Curtis.

Mrs Reardon flung up her hands and turned to face him.

‘What was he? Friend, secretary, factotum … anything and everything or nothing. He seemed to do mostly what he liked.’

‘He had no fixed appointment with Edgar?’

‘I couldn’t tell you. I don’t think Edgar would have tolerated the man unless he had been useful for something. I only hope that it was nothing disgraceful.’

Curtis elevated his eyebrows, looked keenly at the widow.

‘Aren’t you being somewhat harsh, Mrs Reardon? Poor Edgar positively basked in affection. Do you think he might have been disturbed by the idea that you and he were drifting a little apart?’

The woman began to tap one foot on the carpet.

‘I have often wondered,’ she replied softly, ‘whether Edgar loved me or whether I loved him.’

Watson interrupted in a voice so strained that Curtis stared.

‘Then why did you marry him, Lola?’

She answered and it seemed almost that she was thinking aloud:

‘You know that I was very young. And Edgar was Edgar. I think he could have persuaded a nightingale to sing out of his hand. But I doubt whether he would have listened to the song.’

Watson burst into a perspiration. He drew a handkerchief and passed it to and fro across his forehead.

‘We’ll leave you now,’ said Curtis, ‘so that you can get to bed.’

The men shook hands with her and left. She was gazing into the fire when the door closed after them.

‘I’m sorry for that little lady,’ said Curtis as they stood at the corner of Downing Street and Whitehall.

‘So am I. It’s a rotten shame. Poor little Lola!’

‘I hate to think of her being harried by Ripple and it looks as though she’s bound to be. Let’s hope that it won’t be too awkward for her. It certainly will be if she’s got a few facts she wants to hide. Those little peccadilloes can be very embarrassing.’

‘Don’t talk like that, Curtis. It isn’t like you to make nasty suggestions. I’ve known her ever since she was a kid, and there’s not one word that can be said against her reputation.’

‘Watson, you speak with the confidence of a father confessor, and with rather more than a confessor’s warmth. I could understand your tone if she were your own wife. If I were you I wouldn’t be so anxious to defend the lady’s good name before it is attacked. If the inquiry digs deep the purity of your motives might be suspected. I’ll remind you that Inspector Ripple is perhaps a coarse-minded man.’