Полная версия

Below the Clock

BELOW THE CLOCK

A STORY OF CRIME

BY

J. V. TURNER

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

DAVID BRAWN

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain for The Crime Club

by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1936

Introduction © David Brawn 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008280260

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008280277

Version: 2018-03-23

Dedication

TO MY FRIEND

JOHN MEIKLE

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Below the Clock

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

BELOW THE CLOCK

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

INTRODUCTION

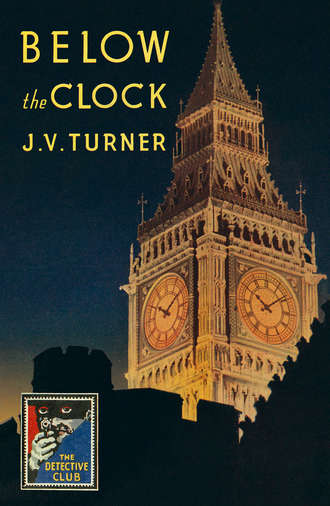

THE Elizabeth Tower is purportedly the most photographed building in the UK, and yet most people would not be able to name it. But as the clock tower that dominates the Palace of Westminster and houses the great bell of Big Ben, it is an instantly recognisable global landmark. Completed in 1859 as part of a 30-year rebuild of the Houses of Parliament after the original palace complex was all but destroyed by fire in 1834, the tower and its clock face quickly became the defining symbol both of the mother of parliaments and of London itself, and the hourly chimes of its 14-tonne bell indelibly associated over 157 years with national stability and resilience. When the bell was silenced on 21 August 2017 for an unprecedented four-year programme of essential maintenance, for some it was as though a death had occurred at the heart of Westminster.

In the annals of crime fiction, of course, deaths at Westminster are all too common. But this was not always the case. When Collins’ Crime Club published J. V. Turner’s Below the Clock in May 1936, the idea of a minister being killed in the chamber was rather sensational, not to say disrespectful of the high office. Ngaio Marsh had dispatched the Home Secretary in The Nursing Home Murder in 1935, although even she hadn’t the audacity to have him drop dead at the Despatch Box. But then Marsh’s stories were not as audacious as those of J. V. Turner.

John Victor Turner, known to family and friends as Jack, was the youngest of three boys in a family of six children. His father Alfred was a saddle-maker, who married Agnes Hume in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester, in 1890. Jack was too young to serve in the First World War, but his eldest brother Alfred (after his father) joined up at only 16 and was profoundly affected by shell-shock for the rest of his life. The middle brother, Joseph, moved to London and joined the police, and eventually attained a senior rank at Scotland Yard. Jack himself attended Warwick School and worked on a local newspaper before moving to Fleet Street, where he worked for the Press Association, Daily Mail, Financial Times and as a crime reporter on the Daily Herald. Turner was seemingly married twice, his first wife having tragically drowned.

At first sight, J. V. Turner was not a prolific author, having written seven detective novels under his own name, all of them featuring the solicitor-detective Amos Petrie, published between 1932 and 1936. However, under the pseudonyms Nicholas Brady and more famously David Hume, Turner wrote almost 50 crime novels in a relatively short writing career. He wrote impressively quickly, publishing up to five books a year, with his obituary in the New York Times claiming, ‘while still in his early thirties [he] was often called the second Edgar Wallace. At one period he wrote a novel a fortnight.’

Some of David Hume’s books bore an author photo and short biography on the back of the dust jacket. Under the heading ‘If David Hume can’t thrill you no one can’, it revealed a little about the author:

‘David Hume has an inside knowledge of the criminal world such as few crime authors can ever hope to command, for he has had first-hand experience of it for over fourteen years. During his nine years as a crime reporter he spent most of his days at Scotland Yard, waiting for stories to “break”. In this way he gained an extraordinarily wide and intimate knowledge of criminals and the methods employed in tracking them down. And his personality is such that he won his way completely into the confidence of the criminals themselves, who revealed to him the precise methods they employ to enter a house or to open a safe. Indeed, no one knows more about the technique of crime or criminal detection: and (we should add) David Hume, far from sitting back on his author’s chair, is taking care to maintain the contacts from which comes the convincing realism that is the greatest feature of his books!’

Hume’s supercharged thrillers, dripping with underworld slang, typically dealt with gangs in Soho and Limehouse and featured Britain’s first home-grown ‘hardboiled’ detective. The Private Eye was an established fixture of the American detective novel by 1932, but when Mick Cardby appeared in the first David Hume novel Bullets Bite Deep, he must have been something of a revelation for readers. Hume’s version of London was a city of gun-toting gangsters, and the fist-swinging Cardby—a detective who tended to rely on brawn rather than brains—offered a refreshingly exciting alternative to the cerebral whodunits that had grown so incredibly popular over the previous decade. Although they would continue to dominate the genre in the years leading up to the Second World War (and arguably beyond), tastes were beginning to change, and as authors and publishers became more innovative, so came diversity within the genre.

Twenty-seven of Hume’s books featured Mick Cardby, two of which were adapted into films: Crime Unlimited (1935, remade four years later as Too Dangerous to Live) and They Called Him Death (1941, entitled The Patient Vanishes). Hume also wrote a trilogy of novels about crime reporter Tony Carter, and under his Nicholas Brady pseudonym he created the eccentric amateur sleuth, Reverend Ebenezer Buckle. But it was using his own name that Turner wrote more traditional detective novels of the kind that are now characterised as ‘Golden Age’, although they had a darker vein running through them than many of their cosier contemporaries. The first, Death Must Have Laughed (1932, published in the US as First Round Murder), was a classic impossible crime story, and featured an amateur detective, the solicitor Amos Petrie, and his long-suffering Scotland Yard counterpart, Inspector Ripple: Below the Clock was their last, and arguably most accomplished, case, and outsold the others—maybe in part thanks to its striking but understated jacket featuring a painting of that famous Westminster clock tower.

As well as writing the hardboiled books (as David Hume) for Collins from 1933 right up to his death in 1945—they were still being published a year after he died—he also participated in the collaborative novel Double Death (1939). Often mistaken for a Detection Club book, on account of its principal authors being Dorothy L. Sayers and Freeman Wills Crofts, in fact it was not, and none of the other collaborators were members of that august body. At Turner’s suggestion, the writers each included notes in the book about the others’ contributions, which although interesting to the fan did rather highlight deficiencies in the novel, which was unfortunate at a time when the ‘round-robin’ format had begun to drop out of fashion. He also co-wrote the screenplay for the 1941 adaptation of Peter Cheyney’s Lemmy Caution novel, This Man Is Dangerous.

Sadly, Turner’s reign as one of the most reliable crime writers in the UK came to a sudden end. On Saturday, 6 February 1945, he died from tuberculosis at Haywards Heath in West Sussex, aged only 39. His early death and the transitory nature of authors’ popularity have sadly resulted in Turner, Brady and even Hume becoming almost entirely forgotten about, and the books very hard to track down. It is to be hoped that the republication of Below the Clock will be the first step towards this remarkable and in many ways trailblazing talent being rediscovered by mystery and crime fans.

DAVID BRAWN

August 2017

CHAPTER I

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

THE House of Commons has its moments.

Ascot bends a fashionable knee to hail Gold Cup Day with an elegant genuflection, Henley hesitates between pride and sophistication to welcome the Regatta, Epsom bustles with democratic fervour as Derby day approaches, Cowes bows with dignified grace as curving yachts carve another niche in her temple of fame, Aintree wakens and waves to saints and sinners on Grand National day, and Wimbledon wallows for a week in a racket of rackets.

The House of Commons has its Budget Day …

The afternoon sun broke into a smile after an April shower, and beamed through the leaded glass in the western wall, throwing lustre on the dark-panelled woodwork, turning brass into a blaze of gold, brightening the faces of Members of Parliament, revealing dancing specks of dust so that they scintillated with the brilliance of diamonds. One widely elliptical ray wandered from the stream of the beams, and bathed the spot where Edgar Reardon, Chancellor of the Exchequer, was to stand. The ray glistened on the brassbound despatch box at the corner of the table and shimmered beyond to waste its beauty on the floor. Nature, in a generous moment, had provided a theatrical spectacle.

The flood of golden light brought no solace to the men who stared at it from above. For the leaders of finance and industry shuffled their feet on the floor of the gallery, and waited for the worst while hoping for the best. They were not thinking of happy omens, portents, and auguries as they eyed the sun beaming on the despatch box. With the passage of years their hopes had faded until budgets meant burdens. Ladies in the grille abandoned their furtive whispers to advance with muffled tread and peer over the brass-work in front of them, looking first of all for relatives, and later, for celebrities.

Members blinked as the sun winked in their eyes. The lambent glow was even noticed by the Cabinet Ministers, who sat out of the beams, arrayed on the Treasury Bench, endeavouring to look as wise as Pythian oracles. The wandering radiance actually distracted attention from Mr Speaker, resplendent in his robes, although an errant ray stabbed a glimmer on the silver buckle of the shoe which he elevated so carefully in the general direction of Heaven. The sun had fascinated the spectators so effectively that few spared a thought for the lesser glories of the Sergeant-at-Arms, although he wore archaic dress, and exercised his privilege of being the only person in the House to bear a sword.

In the minds of the onlookers the sunbeams had one competitor. They were thinking of the man for whom the vacant place on the Treasury Bench had been reserved—and of his deficit!

A stranger casting a casual glance round the House might well have imagined the Members as wholesale breakers of minor laws. For each one apparently held a police summons in his hand. But they were not summonses—only blue papers giving details of how the deficit was made up, but not a single hint of how it was to be met. The filling of the gap between revenue and expenditure was reserved for a white paper, perhaps so coloured to signify the cleansing power of gold, maybe so blanched to prepare the nervous for the shock, but never issued until industry trembles and the City is at rest.

Joe Manning, the Opposition leader, flung down his blue paper as though the sheet were wasp-ridden and turned to Fred Otwood—a small, beetle-browed man who had been Chancellor in the previous Government, and hoped to repeat the performance in the next.

‘Fred,’ said Manning aggressively, ‘if Reardon runs his household as he does national finance the bailiffs would have called on him long ago. As a Chancellor of the Exchequer he’d make a good confidence man.’

‘I said that last year,’ remarked Otwood wearily, ‘and the tale’s getting a bit worn at the corners. No sense in attacking Reardon whatever he says. After all, Joe, somebody has always to pay.’

Manning pulled his whiskers into a new shape and looked at his lieutenant somewhat critically. There were times when Otwood seemed to lack all the requisites for instructing and moulding public opinion. The former Prime Minister glanced away from the sunlight and looked along the line of faces on the Treasury Bench.

‘I can’t understand it,’ he remarked. ‘They’re all smiling as if they were disposing of a surplus. Anyone would think that Willie Ingram had arrived to give a present to the nation.’

Ingram, the Prime Minister, had a flabby face, a fleshy nose, an outsize in eyebrows, and a polished skull. The eyes redeemed other features. They were brightly keen and puckishly humorous.

‘He must think he’s backing a winner,’ said Otwood.

Joe Manning continued to stare at them until he suddenly gripped Otwood’s arm and whispered another pointer for his forthcoming speech:

‘Callous indifference, Fred. That’s the note to strike.’

‘Perhaps it’s still a good line, Joe, but doesn’t it begin to sound a bit like a cracked gramophone record?’

The conversation was halted by a new arrival. Tranter, a doctor from the north, made his way with difficulty to a place behind them, and sat perched upon the knees of two unwilling supporters. Tranter had one fixed panacea for political ailments, but each time he produced it with the earnestness of an original performer.

‘Couldn’t we make a stand for inflation?’ he whispered. Currency inflation was Tranter’s method by which money could be raised without anyone paying for it. As he received no reply he moved away, satisfied that he had struck another blow for national welfare. Fortunately, he did not hear Otwood’s comment:

‘If that man, Joe, had studied medicine as he’s studied economics he wouldn’t know enough to bandage a cut finger.’

Manning tugged more viciously at his moustache and peered anxiously at the clock. During all this time the ritual of question time was proceeding, carried on by a scratch crew under the guidance of Mr Speaker. People grew restless, whispers increased, feet shuffled.

There was a crowd at the Bar. Eric Watson, Parliamentary Private Secretary to Mr Chancellor Reardon, sat with his face bathed in the sunlight. He ought not to have been there. On such a day there must have been many other things for him to do. But the occasion was great, and Watson took his share of the limelight, basking with the self-importance of a cock pheasant flaunting before a hen at mating time.

Watson had made a name for himself by a couple of striking speeches. Now he was consolidating his position, pushing steadily towards minor office in the recognised way—by bottle-washing for someone who had already arrived. He was tall and too handsome. The fine features suggested—to those who were unkind—that strength might have been sacrificed in the process of modelling. He looked round the House, and spoke with unnecessary emphasis:

‘Wait until Edgar comes. He’ll tickle them up more than a bit.’

A Member sitting behind him chuckled softly. It was Dick Curtis, yet another who had joined the long procession and added politics to a legal profession. Curtis imagined that the ranks were full in the present Government. Perhaps that explained why he belonged to the Opposition.

‘He may find that he’s tickling a pike instead of a trout,’ he said. ‘Deficits are not like air bubbles. They won’t be burst and they refuse to blow away.’

Watson smiled tolerantly. He had faced Curtis in many a wordy war in the Law Courts, knew his gift for banter, his flair for argument. Curtis had a full, round voice, and a tonal range that embraced most varieties of expression. Some air of prosperity was conveyed by the figure which indicated the commencement of a senatorial roundness. His next words showed that his banter covered a judicial brain:

‘Reardon’s got one great thing in his favour, Watson. The City isn’t frightened of him. I know the Account that’s closed resembled business in a deserted village, but there was some brisk buying on the Stock Exchange before that. From your pestilential point of view that’s not a bad sign.’

‘Reardon is pleased about that,’ whispered Watson. ‘I know he wants to carry the City with him.’ He spoke as though he had rendered more than a little assistance to his chief in the bearing of the burden.

‘He doesn’t seem in any hurry to arrive,’ said Curtis. ‘Wife with him?’

Watson nodded a wordless affirmative.

‘I thought so,’ remarked Curtis dryly. ‘She’ll be keeping him.’

The Parliamentary Private Secretary seemed disinclined to discuss women in general, or his chief’s wife in particular. He changed the subject with surprising abruptness:

‘Tranter is jumping your seat, Curtis. Turf him out of it.’

Curtis looked lazily. A silk hat threw the light back from his seat like a reflecting glass. His eyes gleamed with humorous brightness.

‘Tranter will soon learn wisdom after I’ve—’

A rising cheer drowned the remainder of the sentence. Mr Chancellor Reardon had arrived in the House.

‘I’ll have to go,’ whispered Watson, hurrying away to return a couple of minutes later with a long glass, filled with claret and seltzer water for Reardon’s use during his speech. The Chancellor interrupted his talk with the Prime Minister to place the glass on the table. As he turned Curtis sat on the hat Tranter had left on his seat. There was a muffled sound of constrained mirth, followed by a peal of loud laughter. The noise increased when Curtis withdrew the hat from beneath him, appeared astonished to find it in his hand, and then held it aloft for all to see. He seemed to have some difficulty in recognising it as a hat.

Tranter snatched the ruin from Curtis’ hand and ran with it up the steps of the gangway. The overhanging gallery offered shelter from derision. The Speaker had to delay his departure from the Chair to restore a sense of responsibility to the House. Even the removal of the mace was attended with the backwash of earlier laughter.

The speech for which the stage had been set, for which the nation waited with apprehension, started in an atmosphere of levity.

As Edgar Reardon stood in the beam of the sun’s spotlight he was revealed to the observant and discerning as a mass of contradictions. The forehead, by its width, depth and sweep, showed intellect, almost patrician nobility; the eyes were vague, flickering and wavering with uncertain darts; his nose was finely chiselled; the mouth was set too low, and the sagging lips might well have fitted a voluptuary; his jaw had the firm, sweeping outline of a determined man; the pale, thin hands moved unceasingly, long fingers wriggling like worms.

The Chancellor had a gift of persuasive speech, and during the customary review of national finance, with which he prefaced the important business, he used the gift to advantage. He reached the end of his preamble at quarter to five. Operators had grown tired of waiting to see the new taxes flashed over the tape machines. But so far Reardon had given no hint of which milch cow he would grasp, of where his money was to come from.

Members leaned forward and there was a perceptible flutter among the financiers and industrialists in the gallery. Relaxed figures became taut.

Mr Chancellor Reardon prolonged the moment of suspense until it became irritating. The way in which the man wasted time was more than exasperating; it was astonishing. He fingered his notes as though he had never seen them before, damping a thin finger on his lips as he turned page after page. He drank from his glass of claret and seltzer, and flicked through his notes again. Perplexity and disquiet increased. Everyone knew that Reardon had worked on the notes for a full week, preparing and arranging them. It seemed that his delay was deliberately insulting, that the Chancellor was verifying unnecessarily that which he must have memorised.

A low murmur rose round the House. The Chancellor was carrying his taunt too far, was playing like a cat with a mouse, refusing to open Pandora’s box until nerves were on edge.