полная версия

полная версияMemoirs and Correspondence of Admiral Lord de Saumarez, Vol. I

"I should observe that we saw three French frigates this morning, but they were not considered of sufficient importance to run the risk of separating the squadron in chasing them. The island of Malta will prove a great acquisition to the French; as well for its excellent harbour as for the immense wealth it contains: they will also get a few ships of war and a considerable quantity of naval stores. D'ailleurs, the suppression of a useless order that encouraged idleness will be no real detriment to the cause of Christianity.

"Sunday, June 24th.—The last two days we have not gone less than a hundred leagues; and, as the wind continues favourable, we hope to arrive at Alexandria before the French, should their destination be for that place, which continues very doubtful. At the same time, if it should prove that our possessions in India is the object of their armament, our having followed them so immediately appears the only means of saving that country from falling into their hands. I therefore hope that credit will be given us for our intentions at least. We have hitherto been certainly unfortunate, which has chiefly arisen from the reinforcement not joining sooner; the French armament sailed from Toulon five days before Captain Troubridge left Lord St. Vincent: another circumstance has been the separation of all our frigates, which deprived us of the means of obtaining information. The day we were off Naples the French fleet left Malta, and it was not until we arrived off that island, six days after, that we heard of its being taken, and that the French fleet had left it; and then without the least intimation which way they were going.

"Sir H. Nelson consulted with some of the senior captains, who agreed with his opinion, that, in the uncertainty where the enemy were gone, the preservation of our possessions should be the first consideration. It may be worth remarking that our squadron was sent, on the application of the King of Naples, for the protection of his dominions. On our arrival there, and requiring the co-operation of his ships, the reply was, that, as the French had not declared war against him, he could not commence hostilities; that if the Emperor declared war, he would also join against France. Should his territories be attacked, he has to thank himself for the event.

"We must hope that in England affairs prosper better than in this country; they are certainly en fort mauvais train in this part of the world.

"Tuesday, 26th.—We are now within one day's sail of Alexandria, so that we hope soon to know whether the French fleet are in this direction; but having seen no appearance of any of their numerous convoy, we begin to fear they are gone some other way. I was this morning on board the Admiral; he has detached La Mutine for information. I hope she will not find the plague there, to which that country is very subject.

"Friday, 29th.—The weather did not permit us to get near Alexandria before yesterday. La Mutine's boat went on shore; and I find this morning from the Admiral that they took us for the French fleet, having had some intimation of their coming this way. We have now to use all despatch in getting back towards Naples; it is probable we shall learn something of them on our passage. The squadron has captured a French ship this afternoon, which we suppose to be from Alexandria. I have passed the day on board the Vanguard, having breakfasted and staid to dinner with the Admiral.

"Sunday, 1st July.—The wind continues to the westward, and I am sorry to find it is almost as prevailing as the trade-winds. The vessel captured the day before yesterday was set on fire, after taking out what could be useful for firewood.

"Sunday, 29th July: off Candia.—A small vessel, captured yesterday by the Culloden, gave some information of the enemy's fleet. The Admiral having made the signal that he had gained intelligence of them, we are proceeding with a brisk gale for Alexandria. If at the end of our voyage we find the enemy in a situation where we can attack them, we shall think ourselves amply repaid for our various disappointments. The Alexander also spoke a vessel which gave information; but, having had no communication with the Admiral, we have not been able to learn the different accounts: we are however satisfied with the purport of the signal he made yesterday.

"Monday.—I find from Captain Ball that the enemy were seen steering towards Alexandria thirty days ago, and we are once more making the best of our way for that place. I also understand that two of our frigates were seen a few days since at Candia; it seems decreed we shall never meet with them. I am rather surprised the Admiral did not endeavour to fall in with them, as they probably have certain information where the enemy's fleet are, from vessels they may have spoken with, and they otherwise would be a great acquisition to our squadron."

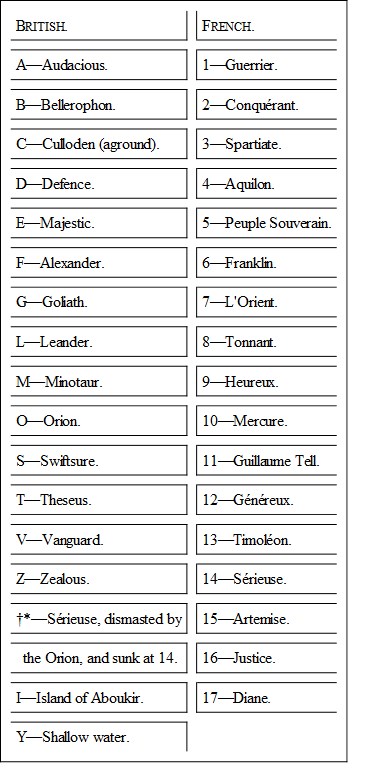

It may now be stated, that in the mean time the French expedition had landed the troops and taken possession, not only of Alexandria, but Cairo; and that their fleet, consisting of thirteen sail of the line, four frigates, two brigs, and several bombs and armed vessels, had taken up a position in the Bay of Aboukir, in which, according to the opinion of their admiral, they could "defy the British navy."

As a particular list of both fleets will be given in a subsequent place, I need now only mention that the force of the British fleet was fourteen ships of seventy-four guns, one of fifty, and the Mutine brig. The fleet was manned with 7,000 men; but as the Culloden, which was not in the action, must not be included, the actual force may be estimated 6,300 men and 872 guns, while the enemy's force, actually opposed, may be reckoned 8,000 men, and 1,208 guns throwing a broadside of one-half more weight than the British.

On the junction of the squadron, the following orders were given by the Admiral:

General Order.

Vanguard, at sea, 8th June 1798.As it is very probable the enemy may not be formed in regular order on the approach of the squadron under my command, I may in that case deem it most expedient to attack them by separate divisions; in which case, the commanders of divisions are strictly enjoined to keep their ships in the closest order possible, and on no account whatever to risk the separation of one of their ships. The captains of the ships will see the necessity of strictly attending to close order: and, should they compel any of the enemy's ships to strike their colours, they are at liberty to judge and act accordingly, whether or not it may be most advisable to cut away their masts and bowsprits; with this special observance, namely, that the destruction of the enemy's armament is the sole object. The ships of the enemy are, therefore, to be taken possession of by an officer and one boat's crew only, in order that the British ships may be enabled to continue the attack, and preserve their stations.

The commanders of divisions are to observe that no consideration is to induce them to separate in pursuing the enemy, unless by signal from me, so as to be unable to form a speedy junction with me; and the ships are to be kept in that order that the whole squadron may act as a single ship. When I make the signal No. 16, the commanders of divisions are to lead their separate squadrons, and they are to accompany the signal they may think proper to make with the appropriate triangular flag, viz. Sir James Saumarez will hoist the triangular flag, white with a red stripe, significant of the van squadron under the commander in the second post; Captain Troubridge will hoist the triangular blue flag, significant of the rear squadron under the commander in the third post; and whenever I mean to address the centre squadron only, I shall accompany the signal with the triangular red flag, significant of the centre squadron under the commander-in-chief.

Gen. Mem.

Vanguard, at sea, 8th June 1798.As the wind may probably blow along shore when it is deemed necessary to anchor and engage the enemy at their anchorage, it is recommended to each line-of-battle ship of the squadron to prepare to anchor with the sheet-cable in abaft and springs, &c.—Vide Signal 54, and Instructions thereon, page 56, &c. Article 37 of the Instructions.

Horatio Nelson.To the respective Captains, &c.

Mem. P.S.—To be inserted in pencil in the Signal-Book, at No. 182. Being to windward of the enemy, to denote that I mean to attack the enemy's line from the rear towards the van, as far as thirteen ships, or whatever number of the British ships of the line may be present, that each ship may know his opponent in the enemy's line.

No. 183. I mean to press hard with the whole force on the enemy's rear.

The proceedings of Sir Horatio Nelson's squadron are now brought down to the moment when their united, ardent, and anxious wishes were to be realized. The disappointments they had met with during their hitherto fruitless pursuit,—the state of anxiety, of alternate hope and despair, in which they had been kept, had raised their feelings of emulation to a pitch far beyond description; this was soon to be manifested by the endeavours of each to close with the enemy.

Never could there have been selected a set of officers better calculated for such a service; Nelson was fortunate in commanding them, and they in being commanded by him. It is true, indeed, that his particular favourite, Captain Troubridge, was intended for his second-in-command, instead of Sir James Saumarez; and the latter would no doubt have been sent home, according to the orders he had received: but, with the chance of such an engagement as that which they anticipated, the well-tried captain of the Orion and his highly disciplined crew could not be spared; and, although Nelson carefully concealed his feelings towards Saumarez, they were but too manifest by the chary manner in which he expressed himself on this and on former occasions.

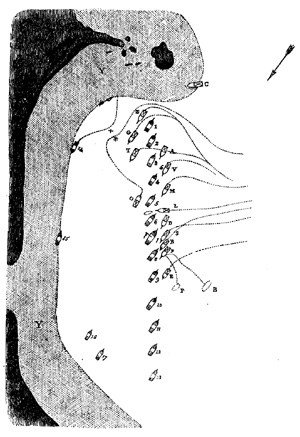

In consequence of the before-mentioned information, the fleet bore up for Alexandria; and on the morning of the 1st of August the towers of that celebrated city, and Pompey's Pillar made their appearance. Soon after was discerned a forest of masts in the harbour, which they had previously seen empty; and, lastly, the French flag waving over its walls. A general disappointment was caused for a short time by a signal from the look-out ships that the enemy's men-of-war did not form a part of the vessels at anchor there; but this was soon dispelled by a signal from the Zealous that the enemy's fleet occupied the Bay of Aboukir in a line of battle, thirteen ships, four frigates, and two brigs, in sight on the larboard bow. At half-past two P.M. the British fleet hauled up, and steered directly for them with a fine N.N.W. breeze, carrying top-gallant sails.13

When the Admiral made the signal to prepare for battle, at half-past three, the signal to haul the wind on the starboard tack, and for the Culloden to cast off her prize, the Swiftsure and Alexander, which had been recalled from looking out off Alexandria, were carrying all sail to join. At five, the Admiral made the signal that it was his intention to attack the van and centre of the enemy as they lay at anchor, which was repeated by the Orion. At forty-five minutes past five, he made the signal to form the line as most convenient. The fleet then formed in the following order:—Goliath, Zealous, Vanguard, Minotaur, Theseus, Bellerophon, Defence, Orion, Audacious, Majestic, and Leander. The Culloden was then astern the Swiftsure, and the Alexander to leeward, tacking to clear the reef. The Admiral hove to, to pick up a boat, and also the four next ships astern of the Vanguard, which gave the Orion an opportunity, by standing on and passing them, to get up with the Zealous at about half-past six.

In ten minutes afterwards the signal for close action was made, and repeated by most of the fleet; at the same time, the Goliath, having passed round the enemy's headmost ship, anchored on the quarter of the second; while the Zealous took her position on the bow of the former ship; both anchoring by the stern. The batteries on the island of Bequir or Aboukir, and the headmost ships, opened their fire as the leading ship approached; and they in return opened theirs on rounding the advanced ship of the enemy's line.

The Orion, after giving that ship her broadside, passed round the Zealous and Goliath; and, as she was passing the third ship of the enemy, the French frigate Sérieuse approached, began to fire on her, and wounded two men. In reply to an observation of one of the officers, who proposed to return her fire immediately, Sir James said, "Let her alone, she will get courage and come nearer. Shorten sail." As the Orion lost way by shortening sail, the frigate came up; and, when judged to be sufficiently advanced, orders were given to yaw the Orion, and stand by the starboard guns, which were double-shotted. The moment having arrived when every gun was brought to bear, the fatal order to fire was given; when, by this single but well-directed broadside, the unfortunate Sérieuse was not only totally dismasted, but shortly afterwards sunk, and was discovered next morning with only her quarter above water.

On discharging this fatal broadside the helm was put hard a-starboard; but it was found that the ship would not fetch sufficiently to windward, and near to the Goliath, if she anchored by the stern. She stood on, and, having given the fourth ship her starboard broadside, let go her bower anchor, and brought up on the quarter of Le Peuple Souverain, which was the fifth ship, and on the bow of Le Franklin, the sixth ship of the enemy's line. The third and fourth ships were occupied by the Theseus and Audacious on the inside, by passing through; while they were attacked on the outside by the Minotaur, Vanguard, and Defence.

By the log of the Orion it was forty-five minutes past six o'clock when that ship let go her anchor, and, in "tending," poured her starboard broadside into the Franklin and L'Orient. The fire was then directed on Le Peuple Souverain, until she cut and dropped out of the line, totally dismasted and silenced.

At seven o'clock the headmost ships were dismasted; a fire-raft was observed dropping down from them on the Orion. Her stern-boat having been shot through, and the others being on the booms, it was impossible to have recourse to the usual method of towing it clear: booms were then prepared to keep it off. As it approached, however, the current carried it about twenty-five yards clear of the ship. About half-past eight, just as the Peuple Souverain, which had been the Orion's opponent, had dropped to leeward, a suspicious ship was seen approaching the Orion in the vacant space which the vanquished one had occupied. Many on board were convinced of her being a fire-ship of the enemy, and Sir James was urged to allow the guns to be turned upon her. Happily he himself had stronger doubts of her being such than those who pressed the reverse. He ordered a vigilant watch to be kept on her movements; and when the darkness dispersed, she was discovered to be the Leander. Distinguishing lights were hoisted, and the Orion continued to engage Le Franklin from fifty minutes past six o'clock to a quarter before ten. The action was general, and kept up on both sides with perseverance and vigour, when the enemy's fire began to slacken, and the three-decker was discovered to be on fire. At ten the firing ceased; the ship opposed to the Orion having surrendered, as also all the van of the enemy.

Preparations were now made to secure the ships from the effects of the expected explosion.—The ports were lowered down, the magazine secured, the sails handed, and water placed in various parts to extinguish whatever flames might be communicated. The unfortunate ship was now in a blaze; at half-past eleven she blew up, and the tremendous concussion was felt at the very kelsons of all the ships near her. The combatants on both sides seemed equally to feel the solemnity of this destructive scene. A pause of at least ten minutes ensued, each engaged in contemplating a sight so grand and terrible. The Orion was not far off; but, being happily placed to windward, the few fiery fragments that fell in her were soon extinguished. Her vicinity to the L'Orient was the happy means of saving the lives of fourteen of her crew, who, in trying to escape the flames, sought refuge in another element, and swam to the Orion, where they met a reception worthy the humanity of the conquerors. The generous, warm-hearted sailors stripped off their jackets to cover these unfortunate men, and treated them with kindness, proving that humanity is compatible with bravery.

About the middle of the action Sir James received a wound from a splinter, or rather the sheave from the heel of the spare top-mast on the booms, which, after killing Mr. Baird, the clerk, and wounding Mr. Miells, a midshipman, mortally, struck him on the thigh and side, when he fell into the arms of Captain Savage, who conducted him under the half-deck, where he soon recovered from the shock it gave him: but although he acknowledged it was painful, and might in the end be serious, he could not be persuaded to leave the deck even to have the wound examined; and the part was so much swelled and inflamed on the next day, that he was not able to leave the ship.

After the pause occasioned by the dreadful explosion, the action continued in the rear by the ships dropping down which were not too much disabled; and Sir James had given orders to slip and run down to the rear, when the master declared that the fore-mast and mizen-mast were so badly wounded, that the moment the ship came broadside to the wind, they would go over the side, particularly the fore-mast, which was cut more than half through in three places. It was therefore determined to secure the disabled masts and repair other damages, while the action was renewed by those that were not so much disabled.

As soon as the battle ceased in the van, by the capture of the enemy's ships, Sir James, who was the senior captain of the fleet, ordered Lieutenant Barker on board the Admiral for the purpose of inquiring after his safety, and of receiving his further instructions. He shortly returned with the melancholy detail that Sir Horatio was severely wounded in the head. At this period, several of the ships of the squadron were still warmly engaged with the centre and part of the rear of the enemy's fleet. Sir James therefore sent a boat to such ships as appeared to be in condition, with directions to slip their cables and assist their gallant companions. These orders were immediately put in execution by that distinguished officer Captain Miller, of the Theseus, and by the other ships that were in a state to renew the action. It has been already stated that the masts of the Orion were too much damaged to admit of that ship getting under way. In the course of the day the whole of the enemy's fleet had surrendered, excepting two ships of the line and two frigates, which escaped from the rear.

Sir James being unable, from the effects of his wound, to wait on the Admiral and offer his congratulations personally, sent him the following letter:

Orion, 2nd August 1798.My dear Admiral,

I regret exceedingly being prevented from congratulating you in person on the most complete and glorious victory ever yet obtained,—the just recompense of the zeal and great anxiety so long experienced by you before it pleased Providence to give you sight of those miscreants who have now received the just punishment of their past crimes. You have been made the happy instrument of inflicting on them their just chastisement; and may you, my dear Admiral, long live to enjoy, in the approbation of the whole world, the greatest of earthly blessings!

I am ever your most faithful and obedient servant,James Saumarez.To Sir Horatio Nelson, &c. &c. &c.

From the character which has already been portrayed of Sir James, the reader will not be surprised to find that the Orion was the first to hoist the pendant at the mizen-peak, and thereby to show an example to the fleet worthy of imitation, in returning thanks to the great Disposer of events and Giver of all victory for that which they had just obtained over their enemies. A discourse on this occasion was delivered by the clergyman of the Orion, which must have made a great and lasting impression on the hearers; but the circumstance, which is much easier to be imagined than described, of a ship's company on their knees at prayers, and offering up a most solemn thanksgiving for the Divine mercy and favour which had been so fully manifested towards them, must have excited feelings in the minds of the prisoners,—the demoralised citizens of the French republic,—which had never before been known to them; and we understand that they did not fail to express their astonishment and admiration at a scene of that kind under such circumstances.

At ten o'clock, when the action had entirely ceased, and the Admiral had received the congratulations of most of the captains of the fleet, the following general memorandums were issued:

Vanguard, 2nd of August 1798, off the mouth of the Nile.The Admiral most heartily congratulates the captains, officers, seamen, and marines of the squadron he has the honour to command, on the events of the late action; and he desires they will accept his sincere and cordial thanks for their very gallant behaviour in the glorious battle. It must strike forcibly every British seaman how superior their conduct is when in discipline and good order, to the notorious behaviour of lawless Frenchmen.

The squadron may be assured that the Admiral will not fail, in his despatches, to represent their truly meritorious conduct in the strongest terms to the commander-in-chief.

Horatio Nelson.To the respective Captains of the ships of the squadron.

Almighty God having blessed his Majesty's arms with victory, the Admiral intends returning thanksgiving for the same at two o'clock this day; and he recommends every ship doing the same as soon as convenient.

Horatio Nelson.To the respective Captains, &c. &c.

Captain Ball, in pursuance of orders from the Rear-admiral, directed the negociation for landing the prisoners on parole. Such as were not Frenchmen were permitted to enter into the English service, for the purpose of conducting the prizes home.

We must refer our readers to the different accounts of this splendid action, which have been published by James, Brenton, Willyams, &c. for the particulars which do not concern the Orion. But we cannot forbear to mention the gallant conduct of Vice-admiral De Brueys, who, according to James and others, "had received two wounds, one in the face, the other in the hand; towards eight p.m. as he was descending to the quarter-deck, a shot cut him almost in two. This brave officer then desired not to be carried below, but to be left to die on deck; exclaiming in a firm tone, 'Un amiral Français doit mourir sur son banc de quart.' He survived only a quarter of an hour." Commodore Casa-Bianca fell mortally wounded soon after the admiral had breathed his last. Captain Du-Petit-Thouars, of the Tonnant, had first both his arms, and then one of his legs shot away; and his dying commands were "Never to surrender!"

Neither must we leave unrecorded the heroic death of young Miells, the midshipman, who we mentioned had been mortally wounded by the same splinter which struck his gallant commander. His shoulder having been nearly carried off, and his life being despaired of, the surgeons were unwilling to put him to needless pain by amputation; but after some hours, finding he still lived, it was determined to give him a chance of recovery by removing the shattered limb. The operation was ably performed by Mr. Nepecker, the surgeon of the Orion, assisted by the surgeon of the Vanguard. The sufferer never uttered a moan, but as soon as it was over, quietly said—"Have I not borne it well?" The tidings were instantly conveyed to his captain, whose feelings may be better imagined than described, and who could only fervently exclaim "thank God!" But his joy soon received a check. Many minutes had not elapsed before he learnt that this amiable and promising youth had been seized with a fit of coughing and expired!