полная версия

полная версияMemoirs and Correspondence of Admiral Lord de Saumarez, Vol. I

In case the enemy should attempt to follow and attack the combined squadron in the rear, besides the continual fire which we ought to make from the stern chasers, chiefly with a view to destroy the enemy's rigging, the squadron will form the line ahead, either with their heads to the Spanish coast, or to that of Africa, as will be determined by signal from the Admiral; and, in order that this might be more simple, in that case, he will only show the signal for the course, at the entire lowering of which the movements must be made. As their situation, from their local position, cannot be of long duration, consequently either by hailing (if near enough) or by signal to preserve the course, the squadron will proceed again to form the line abreast as formerly. It is of the utmost importance that the fire from none of the ships should interfere, or be embarrassed with that of others in this squadron, nor leave the three French ships in the rear.

As soon as the French ships get under sail, all those in my charge will do the same, following the track of each other, always observing to keep at a short distance from the French, till we weather the Point of Carnero, in order that if the enemy should get under sail, and find themselves in a situation to offer battle to our squadron before it is formed in the Straits with the line abreast as above directed, we may engage them with advantage; consequently, the least inattention or delay may produce the most unfortunate consequences.

I think the captains of the ships I have the honour to command are fully persuaded of this truth, and therefore I depend upon its efficacy; and I flatter myself that they are convinced everything will be performed on my part which can be inspired by my wish to add to the glory of his Majesty's arms, that of our corps in particular, and the nation in general.

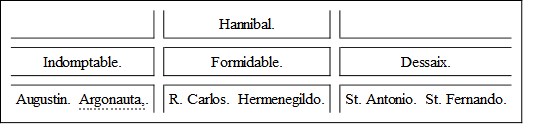

Line of battle in natural order

A red pendant, under any other signal, signifies it is directed to the French ships only.

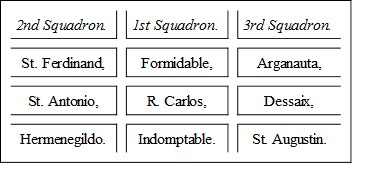

To those conversant in naval affairs, it must appear manifest that the disposition made by Admirals Moreno and Linois was one of the worst that could be devised. It was scarcely possible that nine ships, which had never sailed in company with each other, could maintain, for any length of time, a line abreast before the wind so exactly as to be able to form in a line ahead when required, especially in a dark night with a strong breeze; and it must be evident that any ship which advanced at all ahead of the others could never get into the line of battle when the signal was made to form it on either tack. Moreno seems to have been fully aware of the probability of the ships firing into each other, yet he made arrangements of all others the least likely to prevent it. Had he formed into two lines ahead, with the disabled ships in advance, he would have obviated the risk of firing into each other, while the one division, by shortening sail, might have given timely assistance to the other which had been attacked.

Nothing can equal the scene of horror which the sudden conflagration produced in these two ships. The collision in which the fore-top-mast of the Hermenegildo fell on board of the Real Carlos, added to the general dismay; and the agonising screams of the unhappy crews, deserted by their countrymen and allies in that dreadful hour, could not fail to pierce the hearts of the brave conquerors; but to render them any assistance while the hostile flag was flying was impossible. The duty of the Admiral was to "sink, burn, and destroy." Seven sail of the enemy's line were still flying from half their force, and he was obliged to leave the burning ships to their fate, and pursue his enemy until his destruction was complete.

The capture of the Hannibal, in which the Spaniards had so distinguished a share, induced a number of the young men of family to embark in the two Spanish three-deckers, in order to convey their trophy to Cadiz, never supposing that the half-demolished British squadron would dare to approach so formidable and so superior a force. This fatal event, while it plunged into distress the whole city of Cadiz, could not fail to create a sensation strongly unfavourable to their new republican allies as the originators of their misery.

END OF THE FIRST VOLUME1

See Addenda.

2

See Addenda.

3

When the action had ceased, Sir Hyde Parker, captain of the Latona and son of the admiral, bore down on the Fortitude, and affectionately inquired for his brave parent, of whose gallantry he had been an anxious eye-witness. The admiral, with equal warmth, assured his son of his personal safety, and spoke of his mortification at being unable, from the state of his own ship, and from the reports he had received of the other ships, to pursue the advantage he had gained, in the manner he most ardently desired.

4

Ralfe's Naval Biography, Vol. ii. p. 378.

5

See Appendix for this memorandum, and for extracts from the Russell, Canada, and Barfleur's logs; also Captain White's reply, and extracts of letters from Sir Lawrence Halsted and Admiral Gifford, who were in the Canada, and Captain Knight's letter.

6

Governor Le Mesurier was brother to Mrs. Richard Saumarez.

7

Sir James's brother.

8

Druid, Valiant, Dolphin, Cockchafer, Active, and Prestwood.

9

See Engraving.

10

See Engraving and Diagram.

11

The San Josef, Salvador del Mundo, San Nicolas, and San Ysidro.

12

See Clarke and M'Arthur's Life of Lord Nelson.

13

In allusion to this memorable event, Sir James writes—"When on the morning of the 1st of August the reconnoitring ship made the signal that the enemy was not there, despondency nearly took possession of my mind, and I do not recollect ever to have felt so utterly hopeless, or out of spirits, as when we sat down to dinner; judge then what a change took place when, as the cloth was being removed, the officer of the watch hastily came in, saying—'Sir, a signal is just now made that the enemy is in Aboukir Bay, and moored in a line of battle.' All sprang from their seats, and only staying to drink a bumper to our success, we were in a moment on deck." On his appearance there his brave men, animated by one spirit, gave three hearty cheers, in token of their joy at having at length found their long-looked-for enemy, without the possibility of his again eluding their pursuit.

14

We may here state that, on the preceding day, Captain Ball had paid a visit to Sir James; and as they were discussing the various points of the battle, he stated to Sir James, that "having been the second in command, he would, unquestionably, receive some mark of distinction on the occasion." Saumarez, in the enthusiasm of the moment, exclaimed, "We all did our duty,—there was no second in command!" meaning, of course, that he did not consider he had done more than other captains; and, not supposing that this observation would come to the ears of the Admiral. But, he afterwards thought, Nelson had availed himself of this conversation, to deprive him of the advantage to which his seniority entitled him, although he fully exonerated Captain Ball of having the slightest intention of communicating to the Admiral anything he could have supposed would be detrimental to his interest.

15

See Clarke and M'Arthur's Life of Nelson, vol. ii. p. 119.

16

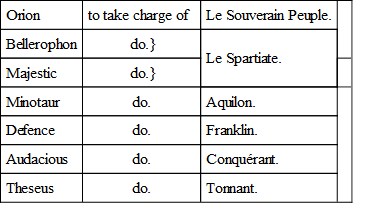

The captains of his Majesty's ships to take charge of the prizes as under:

To the captains of above-mentioned ships. H. N.

17

Sir James displayed a remarkable instance of presence of mind and unhesitating decision in this unexpected case of extreme danger. Captain John Tancock, who was then lieutenant of the watch, and who, having served under Sir James during the whole of the war, enjoyed his perfect confidence, anticipated the captain's wishes in volunteering on this occasion to go up to the mast-head and look out for rocks, and thus considerably relieved his anxiety. The prizes were quite unable to beat to windward, and, in order to be extricated from the peril which the shift of wind had occasioned, their signal was made "to keep in the Orion's wake." Sir James having determined to push on, as the most probable means of saving his inefficient squadron, the "helm was put up," and orders given to steer through a passage between islands, which was marked "doubtful" in the charts, and in which shallow water was soon discovered by Mr. Tancock, who gave timely notice to the helmsman on their approach to each danger. The rest of the ships kept close in the track of the Orion, and in this manner the whole of the squadron and prizes passed between the islands and breakers without accident; and there can be no doubt that their safety was owing to the skilful and decisive conduct of Sir James. It is but justice to add, that, in approving of Mr. Tancock's very meritorious conduct, he emphatically assured him that "he should never forget that he had so fully anticipated his wishes."

18

Vanguard, September 1st, 1798.My dear Sir,

From what I have heard, and made up in my own mind, I feel it is absolutely necessary that I should order the Minotaur and Audacious to quit your squadron when you are in the fair way between Sardinia and Minorca, and join me at Naples; and also with as much salt provisions as can be got out of the ships victualled for six months, reserving only one month's at whole allowance. My squadron are at two-thirds of salt provisions, making the allowance up with flour; therefore you will direct the same in yours. I have put down the number of casks of beef, pork, and pease, which can be easily spared if the commander-in-chief's orders for victualling have been obeyed. Audacious is, I fancy, short of salt provisions, not knowing of coming so long a voyage. If you can manage to let those ships have any part of their officers and men, it will be very useful for the King's service; but of this you must be the best judge. Retalick will tell you all the news from Rhodes, and I was rejoiced to see you are this side of Candia.

Ever yours most truly,Horatio Nelson.To Sir James Saumarez, &c.

Your squadron evidently sails better than Culloden. The Bellerophon sails so well that Darby can take very good care of Conquérant; and Aquilon seems also to sail remarkably well. Remember me kindly to all my good friends with you.

Orion, at sea, 1st September.

My dear Admiral,

Captain Retalick has just joined me with your order respecting the Minotaur and Audacious, both which ships are to be detached for Naples so soon as we are in the fair way between Sardinia and Minorca, with as much salt provisions as can be spared from the ships victualled for six months; which shall be duly complied with. I shall also take from the prizes as many of the officers and men as can be replaced from the ships left with me, which I shall endeavour to be as near the full number as can be thought prudent. Wishing to use as little delay as possible, not to detain the Bonne Citoyenne,

I am very truly, &c.James Saumarez.To Sir Horatio Nelson, K.B.

Orion, at sea, 1st September.

My dear Admiral,

After contending for three days against the adverse winds which are almost invariably encountered here, and getting sufficiently to the northward to have weathered the small islands that lie more immediately between the Archipelago and Candia, the wind set in so strong to the westward Thursday morning, that I was compelled to desist from that passage, and bear up between Sargeanto and Guxo, a narrow and intricate channel; but which we happily cleared without any accident, the loss of a few spars excepted, which are now replaced; and we are proceeding as fast as the wind will admit to our destination. The ships are all doing as well as possible; the fever on board the Defence fast abating, and the wounded in Bellerophon, Majestic, and Minotaur daily recovering. Seeing the Citoyenne on her way to us, I seize the opportunity to give you the information.

I am, my dear sir, &c.James Saumarez.To Sir H. Nelson, K.B.

Orion, at sea, 5th Sept. 1798.

My dear Admiral,

Since the receipt of your letter of the 1st instant, containing an order for the Minotaur and Audacious to join you at Naples, I have been employed in making the necessary arrangements for the distribution of prisoners from the ships that remain with me. I fear the quantity that can be spared, after reducing ourselves to four weeks at whole allowance, will fall very short of what you mention. The order for the ships to be put to two-thirds' allowance was given the day after I received your letter. With regard to the men belonging to the Minotaur and Audacious on board the prizes, I hope to have it in my power to meet more fully your expectations, as I see no reason why these men should not be almost entirely replaced from the ships with me, the Bellerophon and Majestic having only fifty men each on board; the Spartiate certainly can spare the same number for Le Conquérant; and I hope to man the Aquilon from the other three ships, except the party of marines, which I shall direct to be left on board of them. We have had favourable winds the last three days, and I hope to-morrow to get sight of Mount Ætna. The enclosed report of a vessel boarded by the Theseus makes me regret the wind did not prove favourable a few days sooner, to have come up with the strayed sheep.

10 o'clock P.M.Captain Renhouse, in the Thalia, has this instant joined me on his return from Bequir. I have taken his letters for the fleet, &c.: and as the Flora cutter is in sight, closing with the squadron, I have detained him till the morning, that he may take from her any despatches she may have for you. I am happy to learn from him that the Lion had joined the squadron off Alexandria. He also informs me that the Marquis de Niza was on his return from Aboukir, highly mortified at having lost the opportunity of distinguishing himself in the action. I am truly, my dear Admiral,

Your faithful and most obedient servant,James Saumarez.To Rear-admiral Sir Horatio Nelson, K.B.

Orion, 6th September 1798.A.M. 7 o'clock.

My dear Admiral,

The Flora did not join me till this instant, owing to the commander's timidity. I was waiting for him the whole night. I thought it my duty to open one of Earl St. Vincent's public despatches, in case they might contain anything that might render necessary any alteration in my present proceedings. I find from them that Colossus is to the southward of Sardinia, with the Alliance and four victuallers: we shall of course keep a look-out for them. This information will enable me to keep rather a greater supply of provisions than I had made arrangements for, having scarcely reserved four weeks to each ship of the squadron. I have charged Captain Newhouse with the Flora's despatches, with orders to proceed in search of you immediately, and also indicated to him the track I mean to pursue, in case you should have occasion to send me further orders, in consequence of your letters from Earl St. Vincent.

I hope you will do me the favour to believe that I have acted to the best of my judgment for the good of his Majesty's service, and that you will approve my having opened one of Lord St. Vincent's public despatches; which it will be satisfactory to me to know from you.

With sincere and best wishes for your healthand every happiness, &c.James Saumarez.To Sir H. Nelson, K.B. &c.

19

See Appendix.(Vol II)

20

The actions of Sullivan's Island, and the Dogger Bank.

21

This was never realised.

22

November 29th, the day appointed for a general thanksgiving for the great naval victories.

23

Afterwards Louis XVIII.

24

Magnificent, Defiance, Marlborough, and Edgar.

25

Superb and Captain.

26

Battle of Alexandria.

27

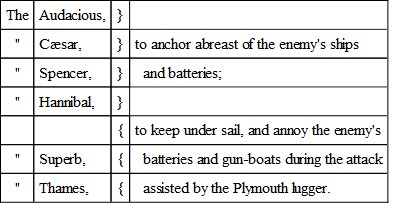

Cæsar, Pompée, Spencer, Hannibal, Audacious, Thames, Phaeton, and Plymouth, hired lugger.

28

See list already given.27

29

Le Formidable, 84. Dessaix, 84. Indomptable, 74: and Meuron, 38.

30

The following memorandum was communicated to the squadron before bearing up for Gibraltar Bay:

Memorandum

Cæsar, 5th July 1801.If the Rear-admiral finds the enemy's ships in a situation to be attacked, the following is the order in which it is to be executed:

The Venerable to lead into the bay, and pass the enemy's ships without anchoring;

The Pompée to anchor abreast of the inner ship of the enemy's line;

The boats of the different ships to be lowered down and armed, in readiness to act where required.

Given on board the Cæsar, off Tariffa,5th July 1801.James Saumarez.To the respective Captains.31

The captain's clerk is stationed in action to take minutes of the events as they occur.

Two other seamen belonging to the Pompée, who had not been selected as part of the reinforcement to the crews of the other ships, secreted themselves on board the Cæsar, and the day after the action presented themselves on the quarter-deck, with a request that intercession might be made for them with their captain, telling their story in the following quaint manner:—"Sir, we belongs to the Le Pompée, and finding our ship could not get out, we stowed ourselves away in this ship, and, in the action, quartered ourselves to the "10th gun, and opposite– on the lower deck," referring, at the same time, to the officer in command of this division of guns, for the truth of their statement.

32

When the French happen to take one of our men-of-war, they do not, as we would do, hoist their own colours over their opponents', but hoist the English ensign union downwards. It so seldom happened that an English man-of-war was taken by the French, that this circumstance was known to very few in the navy, and consequently, the ensign reversed was known only as the signal of distress used by merchant-ships.

33

James, vol. iii. p. 120.

34

The discrepancies between the diagram and some of the statements given in the logs, are easily accounted for by the changes which took place in the positions of the ships during the action.

35

The journal of Lieutenant Collis of the Venerable, the officer who was sent to assist the Hannibal, and was taken prisoner when on board, but who was sent to Gibraltar on parole, need not be given, as it is an exact copy of the captain's log.

36

This was a gratuitous falsehood.

37

While off Europa point, and probably at the distance of more than half a mile, a boat with two men was observed pulling towards us, and, on coming alongside, the men proved to be two of our own people, who had been wounded in the action of Algeziras, and sent to the hospital at Gibraltar. On seeing the ship under sail, with the evident intention of attacking the enemy, these gallant fellows asked permission of the surgeon to rejoin their ship, and being refused, on account of their apparent unfitness, they made their escape from the hospital, and taking possession of the first boat they could find, pulled off to the ship.

38

See page 388

39

M. Dumanoir le Pelley is in error here. The Pompée was not in this action. It has been seen that she was lying disabled at Gibraltar.