полная версия

полная версияPicturesque Pala / The Story of the Mission Chapel of San Antonio de Padua Connected with Mission San Luis Rey

The food which they gave us was a surprise; it was far better than we had found the night before in the house of an Austrian colonel's son, at Pala. Chicken, deliciously cooked, with rice and chile; soda-biscuits delicately made; good milk and butter, all laid in orderly fashion, with a clean tablecloth, and clean, white stone china. When I said to our hostess that I regretted very much that they had given up their beds in my room, that they ought not to have done it, she answered me with a wave of her hand that "It was nothing; they hoped I had slept well; that they had plenty of other beds." The hospitable lie did not deceive me, for by examination I had convinced myself that the greater part of the family must have slept on the bare earth in the kitchen. They would not have taken pay for our lodging, except that they had had heavy expenses connected with Margarita's funeral.... We left at six o'clock in the morning; Margarita's husband, the "captain," riding off with us to see us safe on our way. When we had passed the worst gullies and boulders, he whirled his horse, lifted his ragged old sombrero with the grace of a cavalier, smiled, wished us good-day and good luck, and was out of sight in a second, his little wild pony galloping up the rough trail as if it were as smooth as a race-course.

Between the Potrero and Pala are two Indian villages, the Rincon and Pauma. The Rincon is at the head of the valley, snugged up against the mountains, as its name signifies, in a "corner." Here were fences, irrigating ditches, fields of barley, wheat, hay and peas; a little herd of horses and cows grazing, and several flocks of sheep. The men were all away sheep-shearing; the women were at work in the fields, some hoeing, some clearing out the irrigating ditches, and all the old women plaiting baskets. These Rincon Indians, we were told, had refused a school offered them by the Government; they said they would accept nothing at the hands of the Government until it gave them a title to their lands.

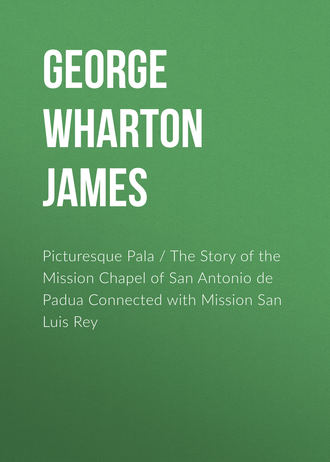

An Old San Luis Rey Mission Indian.

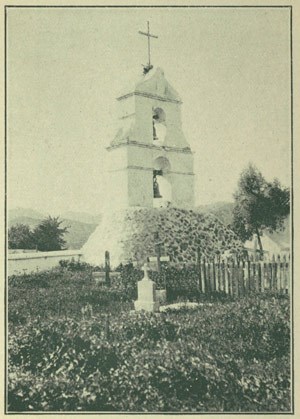

The Pala Campanile from the Graveyard.

Just Entering Pala Valley on the Road from Oceanside.

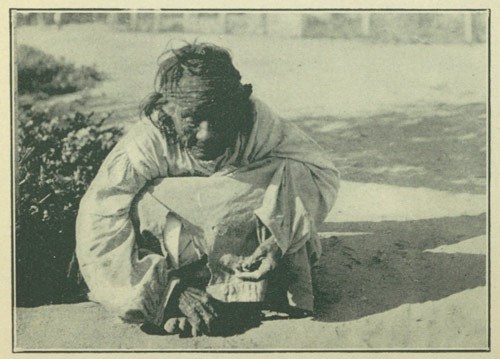

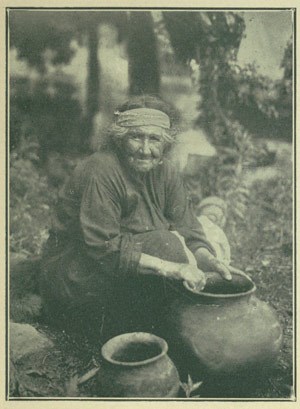

An Ancient Pala Indian.

CHAPTER VII.

Further Desolation

Cursed by the common fate of the Missions Pala suffered severely. In thirty years all its glory had departed as Mrs. Jackson graphically pictures in the preceding chapter. But Pala was destined to receive another blow. This is explained by Professor Frank J. Polley, formerly President of the Southern California Historical Society. In the early 'nineties he visited Pala and from an article published by him in 1893 the following accompanying extracts are quoted:

Mr. Viele, the present owner of most of the old Mission property, is the only white man residing nearby. His store and dwelling is a long, low adobe, opposite the church. Nearby is his blacksmith shop, and in the open space between the church ruins and the river are the remains of the brush booths used by the people at the yearly festival, and these, with the remnants of the mission buildings, corral walls, and the quaint Indian church with its beautiful bell tower, constitute the Pala of today.

The question naturally arises: How did Mr. Viele gain possession and ownership of the Mission property? In the course of his narrative Professor Polley gives the answer:

Trading with the Indians is a slow but simple process. An uncouth Indian figure in strange garb will silently enter the store, and, with hat in hand, stand motionless in the center of the room until Mrs. Viele chooses to recognize him. Then follow rapid sentences in the guttural tone, she executes her judgment in supplying his wants and hands out the parcel, but the figure stands silently and motionless as before. Time passes, and soon the Indian is leaning against the center post. A little later the position is swiftly changed, and next when one thinks of him the figure has vanished and rejoined the group who are smoking their cigarettes by the fence. Money is seldom paid until after their crops are sold. With the squaw the transaction is different in this respect. Like her European sister, every piece of cloth has to be unrolled before purchasing; otherwise it is much the same as with the men. Both men and women are very coarse, education and morality are on a very low plane, the marital vow seems to be but little regarded, and it is no uncommon thing to see, within the shadow of the mission walls, five or six couples living in common in one room. The race is fast dying out from disease, for which the white people are largely responsible. Unable to cope with these new ills, suspicious of the government doctor, and treated like common property by the lower white element in the mountain regions, the Indians are jealous and distrustful of all; even the sick, instead of being brought to the settlement for treatment, are secreted in the hills. One old squaw of uncertain age came each day in a clumsy shuffle to the gate, and there sank her fat body into an almost indistinguishable heap of rags and flesh. The gift of a cigarette would temporarily arouse her to animation; otherwise she would sit there for hours, apparently oblivious to all that was passing, and certainly ignored by all in the house except myself. The education of the Indian here is a serious problem. They do not attend the county school, nor are they encouraged to come, as their morals are demoralizing to the rest of the class. The chief, or captain, is elected by the tribe, and, though only about 30 years of age, the present one has had his position a long time. His duties are light, and he is careful in executing his authority. He is a reasonably bright fellow, speaks English fairly well and often succeeds in securing justice for his tribe in the way of government supplies. The balance of his time he cultivates a little patch of garden, and seems to enjoy life after the Indian fashion.

Procuring the church keys was not so simple a matter, as the building is now closed and services are held at very rare intervals. This is the result of litigation. The law has invaded this sheltered haven. Years ago, when times were different and the mission was making some pretense to be a living church, in the course of their duties a party of government surveyors came here. As a result of their surveys one of them told Mr. Viele in confidence that the entire mission holdings, olive orchards and lands were all on government property. Mr. Viele at once took steps to claim all, and did so. The secret leaked out, and others came in and attempted to settle on parts of the property under various claims of title, and soon the Catholic church and the claimants were engaged in a long lawsuit, which proved the death struggle of the church's interests. Mr. Viele emerged victorious, sole owner of the church, the orchard, the bells, and even the graveyard. Afterward, by deed of gift, he gave the church authorities the tumble-down ruin of the church, the dark adobe robing room, the bells and the graveyard, but, because Mr. Viele still withheld the valuable lands from the church, no services are held there, and the quarrel has gone on year by year. Mr. Viele clings to what he terms his legal rights, and the church is locked up and the Indian left largely to his own devices. Once in possession of the keys, we found them immense pieces of iron, and it took some time to unlock the door. The services of one of the Indian pupils materially assisted us in our investigations. The church is a veritable curiosity, narrow, long, low and dark, with adobe walls and heavy beams roughly set in the sides to furnish support for the roof. Canes and tules constitute this part of the structure. The earthen walls are covered with rude paintings of Indian design and of strange coloring that have preserved their tone very well indeed. Great square bricks badly worn pave the floor, and, set in deep niches along the walls at intervals, are various utensils of battered copper and brass that would arouse the cupidity of a collector of bric-a-brac. The door is strongly barred and has iron plates set with large rivets. The strange light that comes through the narrow windows and broken roof sheds an unnatural glow on the paintings upon the walls and puts into strange relief the ruined altar far distant in the church. Three wooden images yet remain upon the altar, but they are sadly broken and their vestments are gone. One is a statue of St. Louis, and is held in great veneration by the Indians. They say it was secretly brought from the San Luis Rey Mission and placed here for safe keeping. When the annual reunion of the Indians takes place this image is decorated in cheap trappings and occupies the post of honor in the procession. The robing room is a small, dark apartment behind the altar, where not a ray of light could enter. We dragged a trunkful of altar trappings and saints' vestments out into the light. The dust lay thickly upon the garments in these old chests, and it is to be hoped that no one with a shade less of morality than we had will ever explore their treasures, or the church may be robbed and the images suffer much loss of their decorative attire. Undoubtedly everything of value has long since been removed, but what remains is very quaint and odd, being largely of Indian workmanship. Everything about this simple structure spoke of slow and patient work by the native workmen, and it needed but little imaginative power to conjure up the scene when men were hauling trees from the mountains, making the shallow, square bricks, preparing the adobe, and later painting these walls as earnestly perhaps as did some of the greater artists in the gorgeous chapels of cultivated Rome. The hinges creaked loudly and the great key grated harshly in the rusty lock as we spent some time in securing the fastenings at our departure. The beauty of the valley and the bright sunlight were in great contrast to the cool shadows of the dimly-lighted church. Once outside, we again made the circuit of the outlying walls, where birds sing and grasses grow from the ruined walls of the adobes. Through gaps in them we passed from one enclosure to another, this one roofless, that one nearly so, and a third so patched up as to hold a few Indians who make it their home, and in tiny gardens cultivate a few flowers or vegetables and prepare their food in basins sunken in the firm earth. A few baskets are yet left in this community, but of poor quality, the more valuable ones having been long since gathered by collectors, or sold and gambled by the Indians themselves. Many curious relics still exist, however, for those who are willing to pay several times the value of each article.

Pala remained in much the same condition described above, its Indians slowly decreasing in numbers, until the events occurred described in the following chapters.

CHAPTER VIII.

The Restoration of the Pala Chapel

In the restoration of Pala chapel the Landmarks Club of Los Angeles, incorporated "to conserve the Missions and other historic landmarks of Southern California," under the energetic presidency of Charles F. Lummis, did excellent work. November 20 to 21, 1901, the supervising committee, consisting of architects Hunt and Benton and the president, visited Pala to arrange for its immediate repair. The following is a report of its condition at the time:

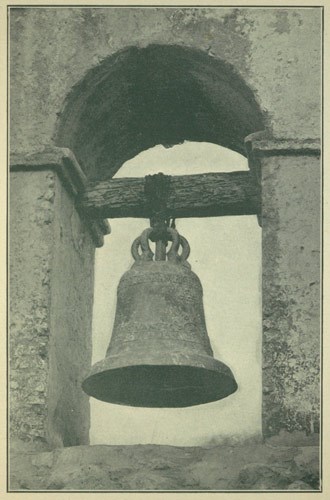

The old chapel was found in much better condition for salvage than had been feared. The earthquake of two years ago—which was particularly severe at this point—ruined the roof and cracked the characteristic belfry, which stands apart. But thanks to repairs to the roof made five or six years ago by the unassisted people, the adobe walls of the chapel are in excellent preservation. Even the quaint old Indian decorations have suffered almost nothing. The tile floor is in better condition than at any of the other Missions, but hardly a vestige of the adobe-pillared cloister remains. Tiles are falling into the chapel through yawning gaps, and it is really dangerous to enter. It will be necessary to re-roof the entire structure. The sound tiles will be carefully stacked on the ground, the timbers removed, and a solid roof-structure built, upon which the original tiles will be replaced. The original construction will be followed; and round pine logs will be procured from Mt. Palomar to replace those no longer dependable. The cloisters will be rebuilt precisely as they were, and invisible iron bands will be used to strengthen the campanile against possible later earthquakes.

Then follows an interesting account of a small gathering, after the committee had formulated its plans, which took place in the little store. Here is Mr. Lummis's account of it:

The immediate valley contains about a dozen "American" families, and about as many more Mexicans and Indians, and about 15 heads of these families were present. After a brief statement of the situation, the Paleños were asked if they would help. "I will give 10 days' work," said John A. Giddens, the first to respond. "Another ten," said Luis Carillo. And so it went. There was not a man present who did not promise assistance. The following additional subscriptions were taken in ten minutes: Ami V. Golsh, 25 days' work; Luis Soberano, 15 days; Isidoro Garcia, 10 days; Teofilo Peters and Louis Salmons, 5 days each with team (equivalent to 10 days for a man); Dolores Salazar, Eustaquio Lugo, Tomas Salazar, Ignacio Valenzuela, 6 days each; Geo. Steiger and Francisco Ardillo, 5 days each. These subscriptions amount to at least $1.75 a day each, so the Pala contribution in work is full $217. Besides this Mr. Frank A. Salmons subscribed $10; and other contributions are expected. It is also fitting that the Club acknowledge gratefully the courtesies which gave two days of Mr. Golsh's time to bringing the committee from and back to Fallbrook, and the charming entertainment provided by Mr. and Mrs. Salmons. The entire trip was heart-warming; and the liberal spirit of this little settlement of American ranchers and Indians and Mexicans surpasses all records in the Club's history. For that matter, while Mr. Carnegie is better known, he has never yet done anything so large in proportion.

In July, 1903, Out West, an account was given of the repairs accomplished. The chapel, a building 144×27 feet, and rooms to its right, 47×27 feet, were reroofed with brick tiles; the broken walls of the entire front built up solidly and substantially to the roof level, the ugly posts from the center of the chapel taken out and the trusses strengthened by the addition of the tension members which the original builders had failed to supply. This greatly improved the appearance of the chapel.

A Pala Pottery Maker.

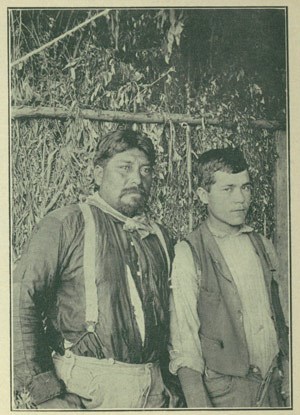

Two Palatingua Exiles, Father and Son.

The Lower Bell in the Pala Campanile.

Another beneficial service rendered was the securing of a deed from the squatter, whose story is told in another chapter, to the picturesque ruins and thus transfering them back to their rightful owners—the Catholic church, in trust for the Indians.

Unfortunately, soon after the Palatinguas came here, the resident priest, whom Bishop Conaty appointed to minister to them, did not understand Indians, their childlike devotion to the things hallowed by association with the past, and their desire to be consulted about everything that concerned their interests. Therefore, being suspicious, too, on account of their recent eviction, they were outraged to find the chapel interior freshly whitewashed so that all its ancient decorations were covered. This was another white man's affront which caused irritation and bitterness that it required months to assuage.

CHAPTER IX.

The Palatingua Exiles

States and nations, even as individuals, are often tempted in diverse ways to forsake the path of rectitude, and, for material gain, territorial acquisition, or other supposed good, to do dishonorable things. To my mind one of the chief blots on the escutcheon of the United States is its treatment of the Indians, and California, as a sovereign state, cannot escape its individual responsibility for its utterly reprehensible treatment of its dusky "original inhabitants."

When the Spaniards seized the land their laws were clean-cut and clear in regard to the confiscation of the lands of the Indians. It was made the duty of certain officials, under direct penalties, to see that they were never, under any excuse, pretense, or even legal process, deprived of the lands they had held from time immemorial. The Mexicans, in the main, effectually carried out the same just and equitable laws. But when the United States took possession of California and the new state government was formally organized, a new idea was interjected. The California law proclaimed its intention to protect the rights of the Indians, but it made it the duty of the Indians, within a certain specified time, to come before a duly authorized officer and declare what lands were theirs and that they intended to claim and use. Now while on the face of it this law seems reasonable and just, in actual practice it is as cruel, wicked, and surely confiscating as is the "stand and deliver!" of the highwayman. How were the Indians to know what was required of them? What did they know of the white man and his laws? As well pass a law that all the birds who do not declare their intention of using the branches of certain trees will be shot if they appear there, as pass laws requiring Indians, ignorant of our language, our methods of procedure, to appear and declare that they intend to continue to use lands they had had uninterrupted possession of for unknown centuries. In other words, the law fiction was a deliberate and definite scheme of dishonest men to make legal the dispossession of the Indians, whenever it was found desirable. Such a case in due time arose at Warner's Ranch. Other cases innumerable might be cited, but this is the one that particularly concerns Pala.

Warner's Ranch was named after Jonathan Trumbull Warner, popularly known to the Mexicans as Juan José Warner, who came from Lyme, Conn., by way of St. Louis, Santa Fe and the Gila River, to California, in 1831. In 1834 he settled down in Los Angeles, marrying, in 1837, at San Luis Rey Mission, Anita Gale, the daughter of Capt. W. A. Gale, of Boston. The maiden, however, had been in California ever since she was five years old, her father having placed her in the home of Doña Eustaquia Pico, the widowed mother of Pio Pico, the last Mexican Governor of California. In due time he (Warner) was naturalized as a Mexican citizen and received from the Mexican Governor in 1844 the grant of an immense tract of land in San Diego County, long known as El Valle de San José. It was fine pasture land, but it was especially noted for its hot springs—Agua Caliente—near which the Indians had had their village from time immemorial. According to Spanish and Mexican law, it must be remembered, their right to their homes and adjacent pasture lands was inalienable without their own consent. Hence under Warner's regime they lived content and happy, uninterfered with, and never worried that a grant—of which they knew nothing—had been made of their lands without any clause of exemption preserving to them their time-honored rights.

Then came Fremont, Sloat and Kearny. California became a state of the United States and among other laws passed the one referring to the lands of the Indians noted above. As he passed by Palatingua, Genl. Kearny, according to the oldest man of the village, Owlinguwush, who acted as his guide, solemnly pledged his government not to remove the Indians from their lands, provided they would be friends of the new people.

This the Indians were. The white people soon learned the value of the hot springs, and flocked thither in great numbers to drink and bathe in the waters. The Indians charged them a small fee for the use of the bath-houses and tubs they had prepared. This added to their modest income, gained from their industries as cattle-men, hunters, farmers, basket and pottery-makers. They were happy, healthy, fairly prosperous and contented.

But in time Warner died. His grant was duly confirmed by the United States Land Courts, but no one cared enough to see that the rights of the Indians were guarded, hence the confirmation and deed of grant contained no exemption of the Indians' lands.

The ownership changed until it came into the hands of a well-known California capitalist. He was not interested in Indians, had no particular sympathy with or for them, and did not see why they should remain on his land. Several times he vigorously intimated that he wanted them to "clear off," he needed the land, and especially he needed the hot springs. There was a strongly expressed desire that a health and pleasure resort be established at this charming place, but, of course, it was impossible so long as the Indians were there. Each time removal was intimated to the Indians they laughed—as children laugh if you tell them you are going to buy them from their parents. Had they not lived here long before a white man had ever set foot on the continent? Were they not born here, raised, married, had their children, died and were buried here for centuries? Had not Spaniards, Mexicans, and even General Kearny assured them they were secure in their possession? Of course they laughed! Who wouldn't?

But the owner of the land grew tired of their smiles. He wanted the place, so his lawyers ordered the Indians to vacate, and the papers were served in such manner that even the childlike aborigines were compelled to realize that something serious was going to happen. But that they should be compelled to leave! Ah, impossible! No one possibly could be so cruel and wicked as that.

The courts were appealed to, and finally the State Supreme Court decided against the Indians, by a vote of four to three—a decision so contrary to the spirit of honor and justice that it aids in making anarchists and revolutionists of good and law-abiding men. Confident in the right of the Indians' cause their faithful friends took the case up to the United States Supreme Court, and again, this time purely on the plea of precedent—that it was contrary to rule for the United States Supreme Court to interfere in any case that was purely domestic to one State—the judgment ousting the Indians was confirmed.

Things now began to look serious. Some of the Indians were crushed by the decision, others were ugly and wanted to fight. Various people of various temperaments interfered, and each one denounced the others as trouble-makers and brewers of mischief. Council after council was held, and at each one the Indians stedfastly refused to leave their homes.

In the meantime, realizing that the suit for eviction most probably would go against the Indians, certain societies and individuals, prompted by their interest in them and by their inherent sense of justice, appealed to Congress to find a new home for these people if they were dispossessed.

For the first time in its history, Congress voted $100,000 to give to these Indians a better home than the one they were to be evicted from. A special inspector was sent out to determine where this new home should be. He reported favorably upon a site, which, however, better informed people in the state, considered altogether unsuitable. Protests immediately were lodged with the Indian Department and as the result a Commission was appointed to investigate conditions, and find the most suitable place to which the Palatinguas could be transferred. This Commission was composed of Charles F. Lummis, Russell C. Allen, and Chas. L. Partridge.

After weeks of careful and patient investigation, criticized on every hand by those who were anxious to sell any kind of an acreage to the Indians, it was finally decided to recommend the purchase of the Pala Valley. Few seemed to see the irony of this decision. The land once had belonged to the Pala Indians. Less than a century before a thousand of them were regular attendants at the little Mission Chapel and devoted friends of Padre Antonio Peyri. Whence had these and their descendants gone? How had they been deprived of their lands? In another chapter I have quoted from Frank J. Polley, how our California laws aided and abetted the spoliators and how Pala unjustly came into the possession of a white man.